Adventure travelers (including bicycle, motorcycle and trekking travelers) and persons who will be in rabies endemic areas for an extended period of time should be vaccinated against rabies prior to travel. After an animal bite, rabies postexposure prophylaxis (passive and active immunization) is always indicated because rabies infection is almost always fatal. Every animal bite requires surgical assessment including irrigation/debridement; primary wound closure should be avoided if possible. Antibiotic prophylaxis for deep or extensive animal bites or bites to the face, hands, or feet is primarily with amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, alternatively with clindamycin and ciproxin. A rodent bite and the clinical triad of fever, exanthema, and arthritis should be considered rat bite fever. Monkey bites can result in infection with herpes B virus, so prophylaxis with valaciclovir should be started.

The most popular travel destinations for the Swiss population are still in Europe, but adventure travel to remote areas where medical care is not readily available is on the rise. Trekking trips in particular are becoming more popular among all age groups, which is accompanied by the immediate increased risk of encounters with (wild) animals. The most common bite injuries while traveling are caused by stray dogs, but bites from wild animals are rare. Dog bite injuries while traveling are associated with an immediate risk of rabies transmission. In Switzerland, decades of measures have succeeded in achieving freedom from rabies in resident and terrestrial animals, but worldwide approximately 60,000 human rabies cases per year continue to be reported.

After the bite: clean and disinfect

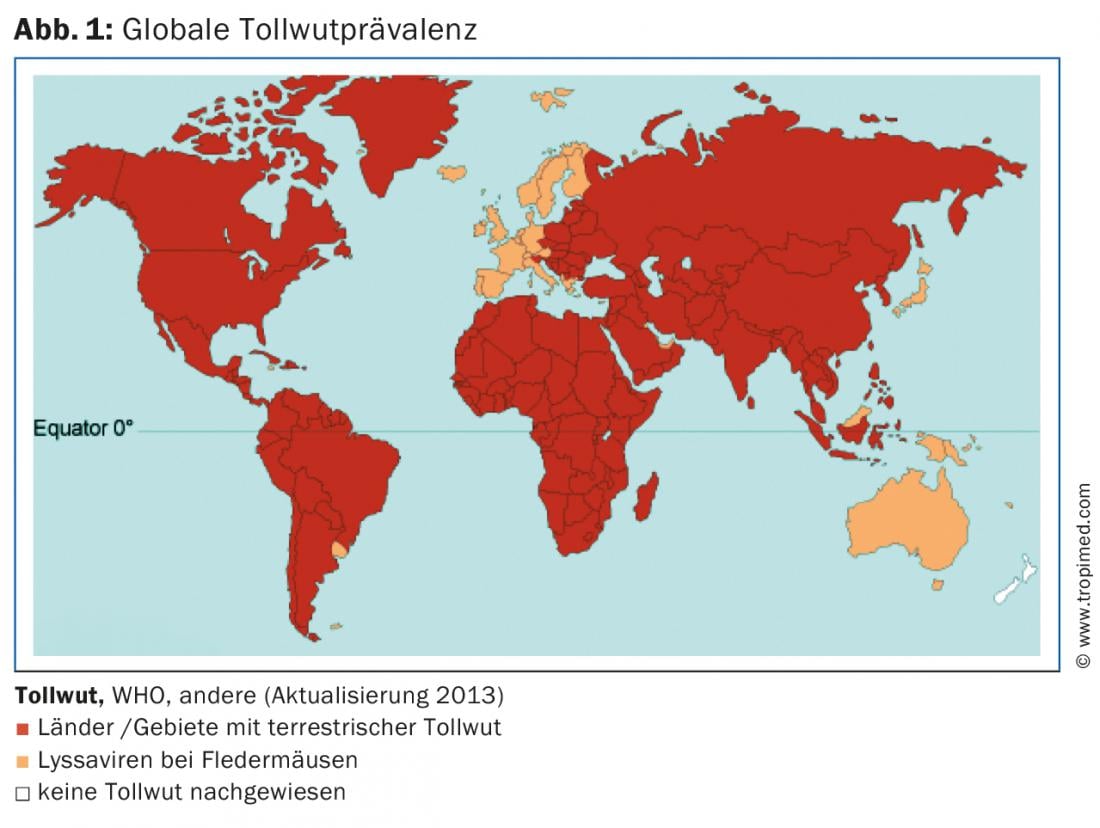

Rabies is a viral infection that spreads through the peripheral nerve tracts after an incubation period of 20-60 days, but in some cases it can take years. It eventually causes encephalitis, which manifests primarily nonspecifically with paresis, lethargy, upset, and excitability, and later with convulsions, and is virtually always fatal. Approximately half of rabies infections occur in the Indian subcontinent. The other cases occur mainly in Southeast Asia, Africa and South America (Fig. 1). The most common source of infection is dogs; in Bangkok, for example, one in ten stray dogs is infected with rabies.

To prevent rabies infection, contact with animals should primarily be avoided during travel. If an injury nevertheless occurs from an animal, especially a dog, cat, fox, bat, raccoon or skunk, the wound must be cleaned immediately with soap and water and disinfected with a disinfectant containing iodine. Regardless of these initial measures, a medical care center – preferably with medical supervision – should be consulted, as rabies infection must always be assumed in unknown and not regularly vaccinated animals [1].

Rabies immunization after a bite

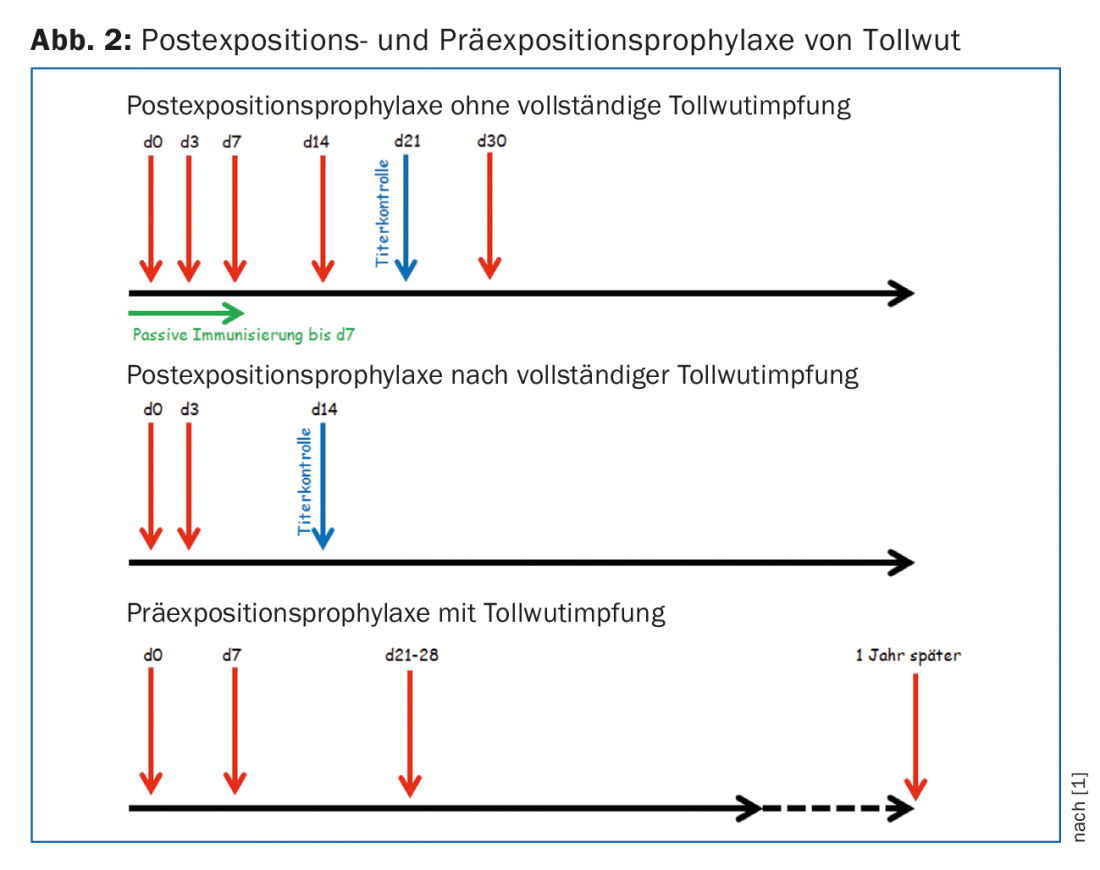

In unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated individuals (i.e. <3 vaccine doses or undocumented vaccinations), active immunization with rabies vaccine i.m. must be started immediately. (Rabipur® or Mérieux®) must be started. The five vaccinations are given on days 0, 3, 7, 14, and 30 (Fig. 2). The dose is the same for adults and children. To confirm the efficacy of vaccination, a serologic check of the rabies antibody titer should be performed on day 21. If a titer of 0.5 IU/ml has not yet been reached, active vaccination must be continued until this titer is reached. In addition, passive immunization with rabies immunoglobulins (Berirab® 150 IU/ml) must be performed as soon as possible, but no later than within the first seven days after the bite. Immunoglobulins are injected at a dosage of 20 IU/kg body weight around the wound if possible, and at the base of the finger in the case of bites to the finger. The remaining amount of immunoglobulins can be injected into the thigh or deltoid muscle.

For previously fully vaccinated individuals with at least three documented doses of vaccine or a documented rabies titer of ≥0.5 IU/ml, two booster vaccinations must be given with the active rabies vaccine on days 0 and 3.

Serological control is performed on day 14 (Fig. 2). Passive immunization can be omitted.

Rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis

The indication for preexposure prophylaxis in travelers depends on the individual risk. Especially backpackers, adventure travelers (incl. trekking) as well as bicyclists and motorcyclists traveling to remote areas far from medical care should be prophylactically vaccinated against rabies regardless of the duration of travel. There is an additional indication for rabies vaccination in case of a stay of more than four weeks in areas with a high prevalence of terrestrial rabies as well as generally in case of long-term stays (>3 months), i.e. especially for employees of development cooperation organizations and their children. In addition, rabies pre-exposure prophylaxis should not be forgotten by persons who have contact with animals for professional reasons (veterinarians, researchers, etc.).

Pre-exposure prophylaxis – in addition to avoiding animal bites – consists of four active vaccinations. After the first three vaccinations (Rabipur® or Mérieux®, days 0, 7 and 21-28) the vaccination protection is sufficient; the fourth vaccination one year later serves to boost the immune response in order to achieve a possibly lifelong vaccination protection (Fig. 2). Even in the case of fully vaccinated persons, however, the two booster vaccinations cannot be dispensed with under any circumstances after an exposure!

A summary of the recommendations can be found at www.guidelines.ch, keyword “rabies”.

Primary wound care for animal bite injuries

Regardless of the risk of rabies, early wound care is critical in the event of an animal bite injury to prevent possible infection. In most cases, a mixed flora is present that largely corresponds to the oral animal flora. Systematic studies exist almost exclusively on dog and cat bites. Their typical bacterial flora includes Pasteurella species, streptococci, staphylococci and anaerobes [2]. Capnocytophaga canimorsus is also typical in dog bites and can lead to fulminant sepsis, especially in immunocompetent individuals. After an animal bite, the primary steps should be careful inspection, cleansing (with 0.9% NaCl, 100-200 ml under pressure), and debridement of the wound to rule out injury to deep-seated structures (tendons, joints, bones, etc.) [3,4]. Debridement is particularly important in all animal bite injuries that tend to have a small but deep puncture wound due to jaw mechanics (e.g., cat bites), as a puncture wound is associated with approximately twice the risk of wound infection compared to a laceration/crush injury. Primary wound closure should be avoided whenever possible; exceptions are wounds on the face that are less than 24 hours old or wounds in areas where wound closure is necessary for cosmetic or functional reasons [3].

Antibiotic preemptive therapy is indicated for deep puncture wounds, wounds with significant necrosis, wounds on the hands and face, and immunosuppressed patients. The first-line antibiotic is amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (e.g., Co-Amoxicillin® 625 mg 3×/day p.o.). Alternatively, the antibiotic combination of clindamycin and ciproxin can be used for allergies. Preemptive therapy lasts 3-5 days [4]. However, close clinical monitoring is essential, and if there are clear signs of infection during the course, the duration of therapy should be extended accordingly. A longer duration of therapy is also indicated for special localizations of the bite with bone or joint involvement. Tetanus vaccination should not be forgotten with every animal bite.

Bites from rats and monkeys

Rats are colonized with Streptobacillus moniliformis or Spirillum minus in 50-100% of cases. If the triad of sudden high fever, myalgias/arthralgias, and maculopapular exanthema or rash occurs after a bite by a rodent. petechial skin symptoms (Fig. 3), then rat bite fever should be considered. Spirillum minus infections, which can lead to ulceration around the bite site, occur exclusively in Asia (especially Japan). In Europe and the USA, however, infections with Streptobacillus moniliformis are expected to cause no ulceration [5]. With an incubation period of up to ten days, a high degree of intuition is therefore required in these cases, where the initial bite wound has usually already healed. Therapy for both infections is with penicillin. If left untreated, these diseases lead to relapsing fever.

Macaque bites carry the risk of infection with herpes B virus. Herpes B seroprevalence in macaques, similar to herpes seroprevalence in humans, increases with monkey age and is 80% in adult Asian macaques >[6]. After a bite, skin efflorescences may develop that would be compatible with a herpes simplex primary infection, and generalized symptoms with fever, headache, nausea, etc. develop. In most cases, encephalitis develops during the course with neurological complications such as ataxia, sensory disturbances, flaccid paresis, and agitation. Therefore, prophylaxis with valaciclovir is indicated after a deep macaque bite – but not after simple contact. The dosage is 1 g 3× per day p.o. for two weeks.

Literature:

- Guidelines and Recommendations Pre-/Postexposure Prophylaxis in Humans, Federal Office of Public Health, Rabies Working Group, Swiss Commission on Immunization, July 2004.

- Abrahamian FM, Goldstein EJ: Microbiology of animal bite wound infections. Clin Microbiol Rev 2011; 24(2): 231-246.

- Boillat N, Frochaux V: Animal bites and infection. Rev Med Suisse 2008; 4(174): 2149-2152, 2154-2155.

- Dendle C, Looke D: Animal bites: an update for management with a focus on infections. Emerg Med Australas 2008; 20(6): 458-467.

- Elliott SP: Rat bite fever and Streptobacillus moniliformis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2007; 20(1): 13-22.

- Estep RD, Messaoudi I, Wong SW: Simian herpesviruses and their risk to humans. Vaccine 2010; 28 Suppl 2: B78-84. or desire: A meta-analysis. Journal of Health Psychology 1993, 1(1): 65-81.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(5): 22-24