Behavioral addictions such as gambling or computer game addiction are increasingly coming into psychiatric focus. The private clinic in Meiringen is also taking this into account by opening a ward for behavioral addictions.

Early sources already show that disorders related to alcohol consumption and gambling were long known in many civilizations [1]. However, the classification of excessive behavior patterns in the addictive disorders or their perception as part of other mental disorders or as a coping mechanism has always been controversial. Until 2018, behavioral addictions were classified as impulse control disorders in the WHO ICD-10 classification.

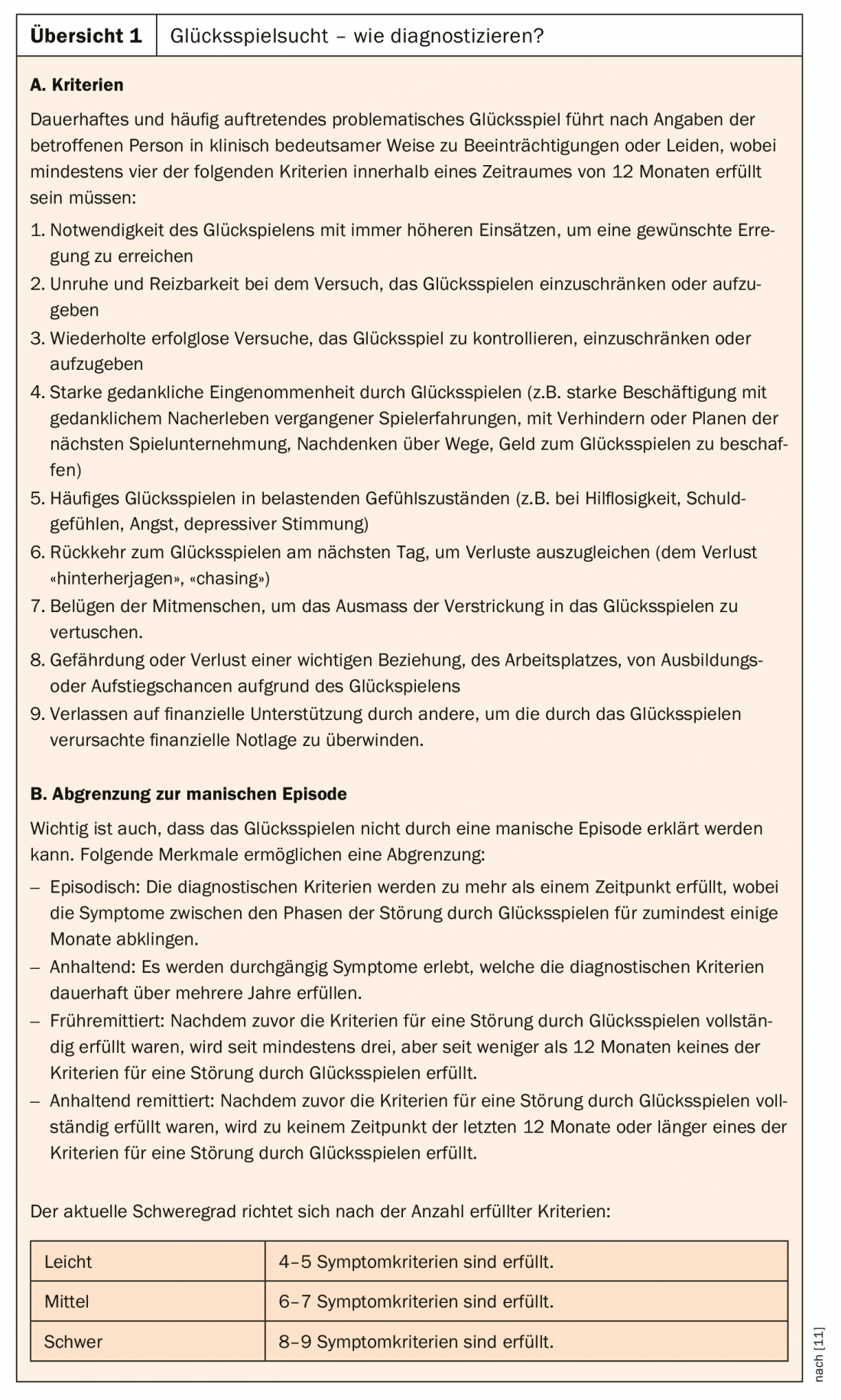

However, already in the American diagnostic manual DSM 3R from 1987, gambling addiction was defined on the basis of symptoms of substance dependence. In the newly published ICD-11, gambling addiction and computer game addiction (“Gambling Disorder”, “Gaming Disorder”) are recognized as behavioral addictions. Gambling addiction was also included as an addictive disorder in the APA’s new DSM 5 (overview). In addition, Internet gambling addiction was listed in the DSM 5 research criteria.

In a position paper, the German Society for Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics and Neurology (DGPPN) currently considers only the data situation for pathological gaming, Internet and computer game addiction to be sufficient to classify these as behavioral addiction [2]. Internet and computer game addiction refers to one or more Internet applications regardless of the Internet access technology used (e.g., smartphone, computer).

Pathological buying has not yet found its way into any of the common classification systems for mental disorders, although it is a long-known and quite common phenomenon that causes considerable suffering among those affected and their families. Kraepelin described derailed buying behavior as early as 1909 in his remarks on “Impulsive Insanity” and chose the term “oniomania” for it [3]. In ICD 11, shopping addiction could at best be coded under behavioral addictions as “other specified disorders due to addictive behaviors” [4].

Excessive sexual behavior has not yet been classified as a behavioral addiction in psychiatric classification systems. Basically, the following applies: The definition of which type of sexuality is considered normal, special or disturbed is time-bound and thus subject to constant change. Furthermore, it is strongly influenced by the cultural context [5].

Epidemiology

Studies on the prevalence of Internet and computer game addiction in the general population indicate a rate of about 1%, and up to 5% among adolescents. In some Asian countries, even significantly higher prevalences are found [6]. According to current prevalence estimates, 1% of 14- to 64-year-olds in Germany are considered addicted to gambling. In childhood and adolescence (14-17 years), an increased prevalence of approximately 1.7% is assumed with regard to problem gambling. Another 3.5% of all gambling-using boys and girls are at risk [7].

To date, there are no valid epidemiological data on the prevalence of shopping addiction, with studies in the United States coming up with an estimated prevalence of 8%, which is consistent with the results of two German representative surveys [8].

In the case of excessive sexual behavior, prevalence rates of 3-6% are assumed for German-speaking countries, which also correspond to more recent US data [5].

Substance and behavioral addictions are comparable

Regarding the pathogenesis of substance-unrelated addictions, psychological and neurobiological variables seem to play an important role, in addition to sociostructural, sociopolitical, and anthropological factors [8]. Studies using imaging methodology have demonstrated that behavioral addictions and substance-related addictions are like disorders of the reward system [1].

An overview of the neurobiological similarities between Internet or computer game addiction and substance dependence is provided by Brand and colleagues [9]. For example, prefrontal brain regions with their connections to the limbic system and anterior striatum seem to be involved in the development and maintenance of Internet addiction [9]. At the level of psychological factors, which constitute the framework of the conditional structure of addiction development in behavioral addictions, learning processes such as classical and operant conditioning are mainly involved [8].

Brand and colleagues propose I-PACE (“Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution”), an integrative model of the development and maintenance of Internet and computer game addiction, based on the behavioral addiction concept: Core characteristics of the person, affective and cognitive processes, coping styles and reduced executive functions are taken into account [10].

Due to comparable neurobiological (influence on the reward system) and psychological (specific conditioning process) characteristics, many scientists and clinicians call for recognizing behavioral addictions alongside substance-related addictions [6].

Psychometric test procedures

For the differential diagnosis of pathological gambling, psychometrically based test procedures exist that have proven themselves in clinical practice and can demonstrate good psychometric validation [6]. The South Oaks Gambling Screen (SOGS), a questionnaire that is available in German as well as 40 other languages, is one of the internationally used methods for assessing pathological gambling [8]. As a time-efficient yet valid procedure, the short Lie/Bet Questionaire deserves special mention [12]. A critical overview of standardized diagnostic instruments for Internet and computer game addiction is provided in a systematic review of epidemiological studies by Kuss and colleagues [13]. There are a number of screening questions and self- or peer-assessment procedures for detecting excessive sexual behavior [5], which are also useful for identifying addictive buying behavior [4].

Comorbid disorders and sequelae

Overall, there is evidence that there is a strong relationship between the occurrence of pathological gambling and substance-related dependence disorders. Affective disorders were identifiable as comorbid mental disorders in a total of 63% of pathological gamblers. Specifically, 57.2% were diagnosed with unipolar depressive disorder [7]. In contrast, bipolar disorders including hypomania occurred in only 7.5% [7].

In terms of comorbid disorders from the neurotic, stress and somatoform disorders, the most notable are anxiety disorders, which occur in 37.1% of pathological gamblers (panic attacks 23.8%; PTSD 15.5%; social phobia 13.4%). Comorbid personality disorders were also found in a large number of those studied [7].

The most common comorbidities in Internet and computer game addiction are harmful use of alcohol, ADHD, depression, and anxiety. The consequences of Internet and computer game addiction may include depressive symptoms, disordered eating behavior, and sleep disturbances [6]. Limitations regarding academic or occupational performance and social problems are also likely to be present as part of the diagnostic criteria of Internet and computer game addiction [6].

Patients with addictive buying behavior also report comorbid mental disorders, such as affective disorders, anxiety disorders, binge eating, substance dependencies, and personality disorders [2].

Data on comorbidities are limited for excessive sexual behavior, which is evidence, among other things, of the heterogeneity of behaviors subsumed under the term “excessive sexual behavior.” However, available data indicate that excessive sexual behavior is associated with affective disorders, anxiety disorders, substance-related and non-substance-related addictions, paraphilias, and ADHD [5].

Therapeutic measures

Treatment of pathological gambling includes cognitive-behavioral therapy programs aimed at achieving abstinence, comprehensive relapse prevention, and long-term stabilization of the patient’s psychosocial functioning level [4]. The outpatient setting usually consists of group sessions with accompanying individual discussions. In this context, exposure treatment is of crucial importance. Inpatient treatment is also part of the therapeutic treatment repertoire.

A major component of treatment for gambling addiction is identifying automated thoughts and dysfunctional behaviors. Adapted SORKC models are often used to promote self-reflection. As an alternative to cognitive-behavioral therapies, other methods (e.g., “motivational interviewing”) may be used [7].

Psychotropic drugs are an additive option for treating pathological gambling addiction. This mainly includes the administration of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors or opioid antagonists, although no clear efficacy has yet been demonstrated in this regard and no drug has been approved [7].

Regarding the treatment of Internet and computer game addiction, various reviews have found that cognitive behavioral therapy helps reduce time spent online and alleviate depression symptoms (recommendation level A). Combinations of CBT with family therapy are also effective (recommendation grade B). For the initial phase of intervention, individual therapy sessions appear to be superior to group treatment (level of recommendation C). The combination treatment of CT and pharmacological treatment is recommended as the most effective approach, although only preliminary findings on pharmacotherapy of Internet and computer game addiction are available to date on therapy trials with the active ingredients naltrexone, methylphenidate, valproic acid, quetiapine, sertraline, bupropion, citalopram, and escitalopram. However, it is recommended that pharmacological treatment of Internet and computer game addiction should be based primarily on comorbidity [6].

In the treatment of hypersexual disorders, the disorder should not be considered as an isolated phenomenon, but work should also be done on associated issues such as relationship skills, knowledge about sexuality, or even self-regulation. Because of the high complexity and heterogeneity of the behavior, experienced clinicians recommend an integrative approach of cognitive behavioral therapy, relapse prevention therapy, psychodynamically oriented procedures, and pharmacotherapy when appropriate [5].

For the addictive buying behavior, Cognitive Behavioral Therapy in groups has been shown to be effective in psychotherapy studies [4]. In this context, the treatment goal of purchase abstinence is not realistic. Rather, the goal is controlled, adequate consumption of goods based on the individual’s financial means. By means of cognitive-behavioral therapy techniques (stimulus control, cognitive restructuring, building alternative behavior, exposure techniques), the emotions, irrational thought patterns, and maladaptive behaviors underlying the pathological buying behavior are to be reflected upon and changed according to possibilities. Psychopharmacotherapy in this regard is still poorly studied. At best, there is evidence that in comorbid anxiety disorders and depression, SSRIs may help improve pathological buying behavior. In addition, there are some promising case reports with dopamine antagonists [4].

Special ward for behavioral addictions at the Private Clinic Meiringen

In view of the increasing importance of behavioral addictions, both in the clinical care situation and in psychiatric and clinical psychological science, a special ward for behavioral addictions will open at the Meiringen Private Clinic on June 3, 2019. This is because, despite ongoing discussions about the concept and nosological classification of behavioral addictions, there is widespread agreement that they are relevant mental disorders requiring treatment.

Inpatient treatment for behavioral addictions is usually initiated when complicated cases with multiple comorbid disorders are present. Further indications for an inpatient treatment setting are multiple unsuccessful attempts at outpatient therapy or if no outpatient therapy facility is available close to home. Low willingness to change, insufficient support from the social environment or permanent unemployment are also indications for inpatient psychiatric treatment [8].

The special care unit for behavioral addictions in Meiringen comprises six to eight patient beds and is mainly aimed at patients with Internet, computer game and gambling addictions. However, patients with shopping addiction, sex addiction, etc. are also admitted, even if these are not yet classified as behavioral addictions in the narrower sense. Crucial are repeated behavioral excesses and significant suffering and impairment in everyday functioning due to loss of control.

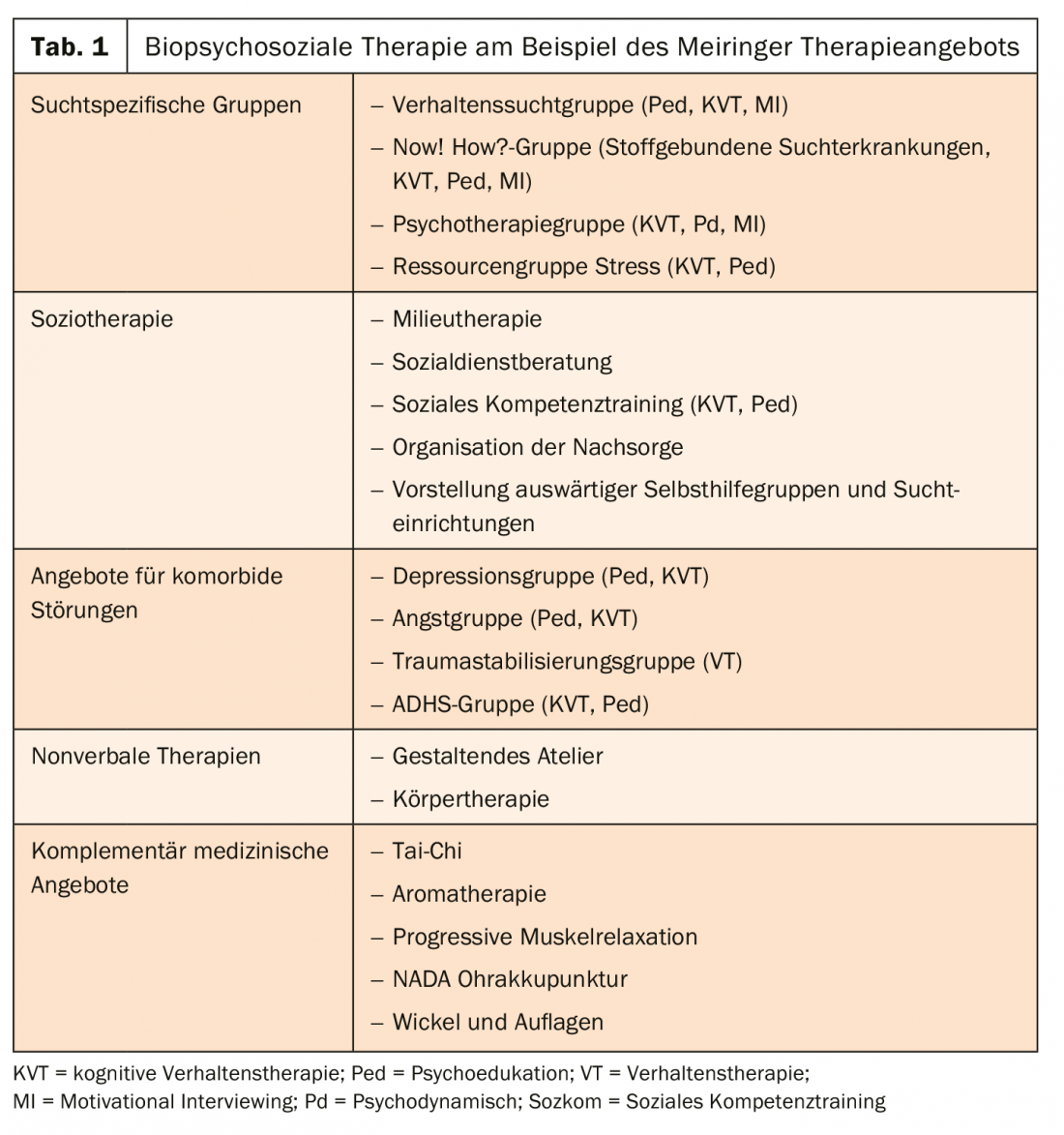

Initial contact is through our behavioral addictions outpatient clinic. If admitted, patients can expect an evidence-based treatment concept based on the biopsychosocial model, which includes verbal and nonverbal, coping and interaction-oriented, mandatory and optional therapy elements within the framework of individual and group therapies. This enables a high treatment density and at the same time offers room for an individual therapy approach. Inpatient treatment is based on addiction-specific treatment elements and has a behavioral therapy and psychoeducational structure (Table 1). As with patients with substance-related addictions, treatment of patients with behavioral addictions is based on an integrative treatment concept with regard to any comorbidities, which is indicated in these situations [14]. Psychotherapy in individual therapy is predominantly behavioral and takes into account the individual problems of the patient. One-on-one interviews are conducted by psychologists, physicians and caregivers.

Take-Home Messages

- Behavioral addictions are becoming increasingly important in psychiatry , which is also reflected in the psychiatric classification system.

- The prevalences of the individual behavioral addictions are sometimes not insignificant.

- Behavioral addictions cause significant suffering and therefore need to be treated.

- Behavioral addictions have high psychiatric comorbidity.

Literature:

- Petersen KU, Hanke S, Batra A: Behavioral addictions. Introduction to the topic. Addiction Magazine 2018; 2: 5-9.

- Expert group on behavioral addictions of the DGPPN: Behavioral addictions and their consequences. Prevention, diagnostics and therapy. Position paper dated 16.3.2016. www.dgppn.de/presse/stellungnahmen/stellungnahmen-2016/verhaltenssuechte.html, last accessed 04 Jun. 2019.

- Kraepelin E: Psychiatry. A textbook for students and physicians. Leipzig: Barth, 1909.

- Müller A, Voth EM: Addictive buying behavior. In: Bilke-Hentsch O, Wölflin K, Batra A, eds: Praxisbuch Verhaltenssucht. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme, 2014: 128-139.

- Berner M, Schmidt HM: Excessive sexual behavior. In: Bilke-Hentsch O, Wölflin K, Batra A, eds: Praxisbuch Verhaltenssucht. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme, 2014: 144-166.

- Petersen KU, Wölfling K: Behavioral addictions. Internet, computer games, buying. In: Soyka M, et al, eds: Addiction Medicine. Munich: Elsevier, 2019: 289-298.

- Wölfling K, Petersen KU: Gambling. In: Soyka M, et al, eds: Addiction Medicine. Munich: Elsevier, 2019: 279-288.

- Müller A, Wölfling K, Müller KW: Behavioral addictions. Pathological buying, gambling addiction, and Internet addiction. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2018.

- Brand M, Young KS, Laier C: Prefrontal control and Internet addiction. A theoretical model and review of neuropsychological and neuroimaging findings. Front Hum Neurosci 2014; 8: 375.

- Brand M, et al.: Integrating psychological and neurobiological considerations regarding the development and maintenance of specific Internet-use disorders. An Interaction of Person-Affect-Cognition-Execution(I-PACE) model. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2016; 71: 252-266.

- Falkai P, et al, eds: Diagnostic criteria DSM-5. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 2015.

- Johnson EE, et al: The Lie/Bet questionnaire for screening pathological gamblers. Psychol Rep 1997; 80(1): 83-88.

- Kus DJ, Lopez-Fernandez O: Internet addiction and problematic Internet use. A systematic review of clinical research. World J Psychiatry 2016; 6(1): 143-176.

- Aichmüller C, Soyka M: Addiction treatment in comorbid mental illness. Neurology 2016; 35(11): 784-791.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(4): 31-35.

GP PRACTICE 2019; 14(8): 43-48