Osteoarthritis is often described as “general joint disease” or “joint wear and tear.” How compatible is this “joint wear” with sports? How can an overloaded or even already worn ankle joint, knee joint, hip joint or shoulder joint (e.g. in artistic gymnastics) still be made to function?

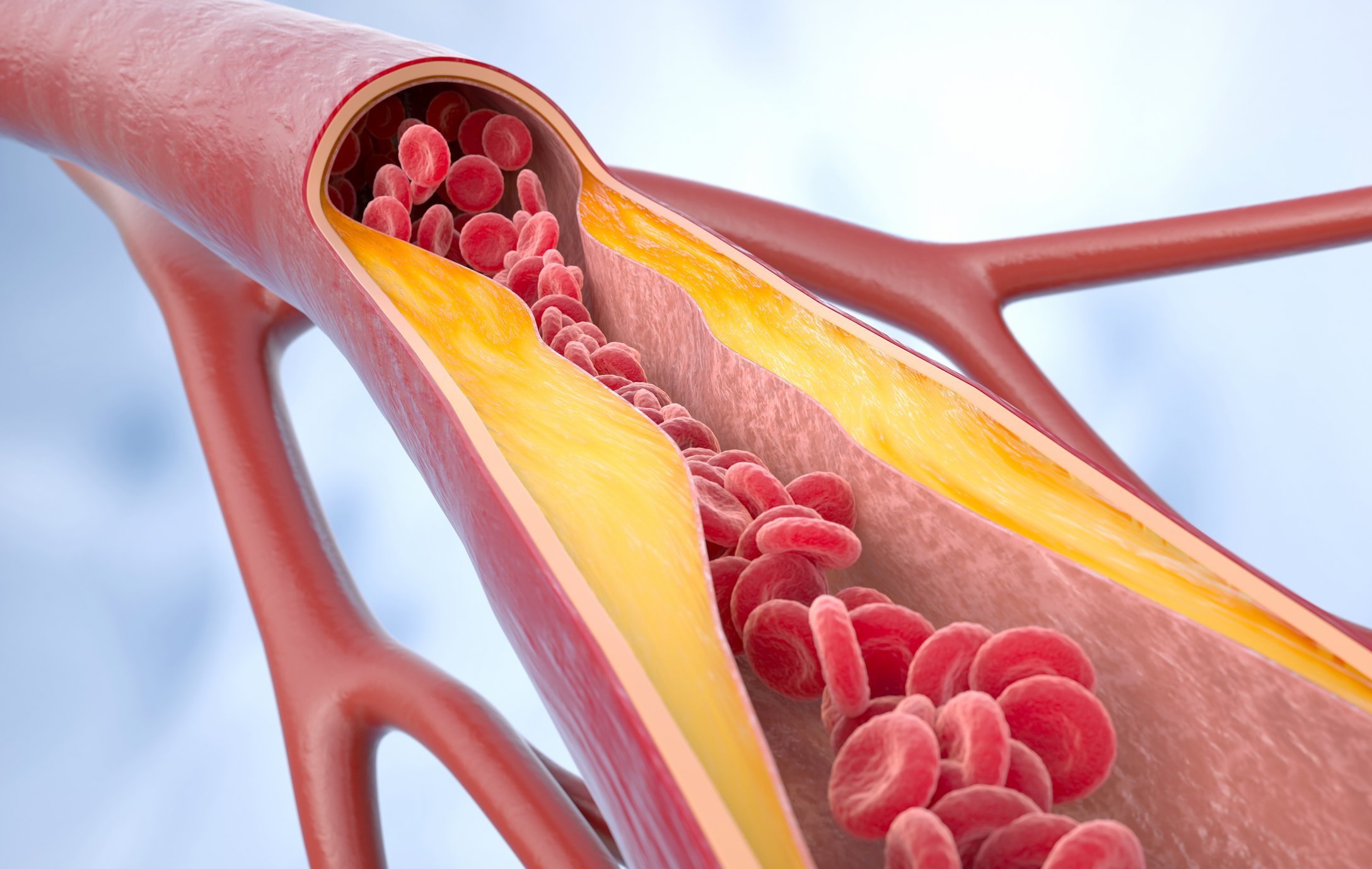

Osteoarthritis is the most common joint disease in Western countries. It can basically occur in any joint, but most commonly in the hip, knee, hands and spine. In osteoarthritis, virtually all parts of the joint are affected in some way at some time: the two joint surfaces with their cartilage coverings, the capsule and, in the knee joint, the two menisci. The abrasive substances usually cause inflammation of the joint capsule with effusion formation, which leads to further disruption and finally to a breakdown of the joint-stabilizing muscles.

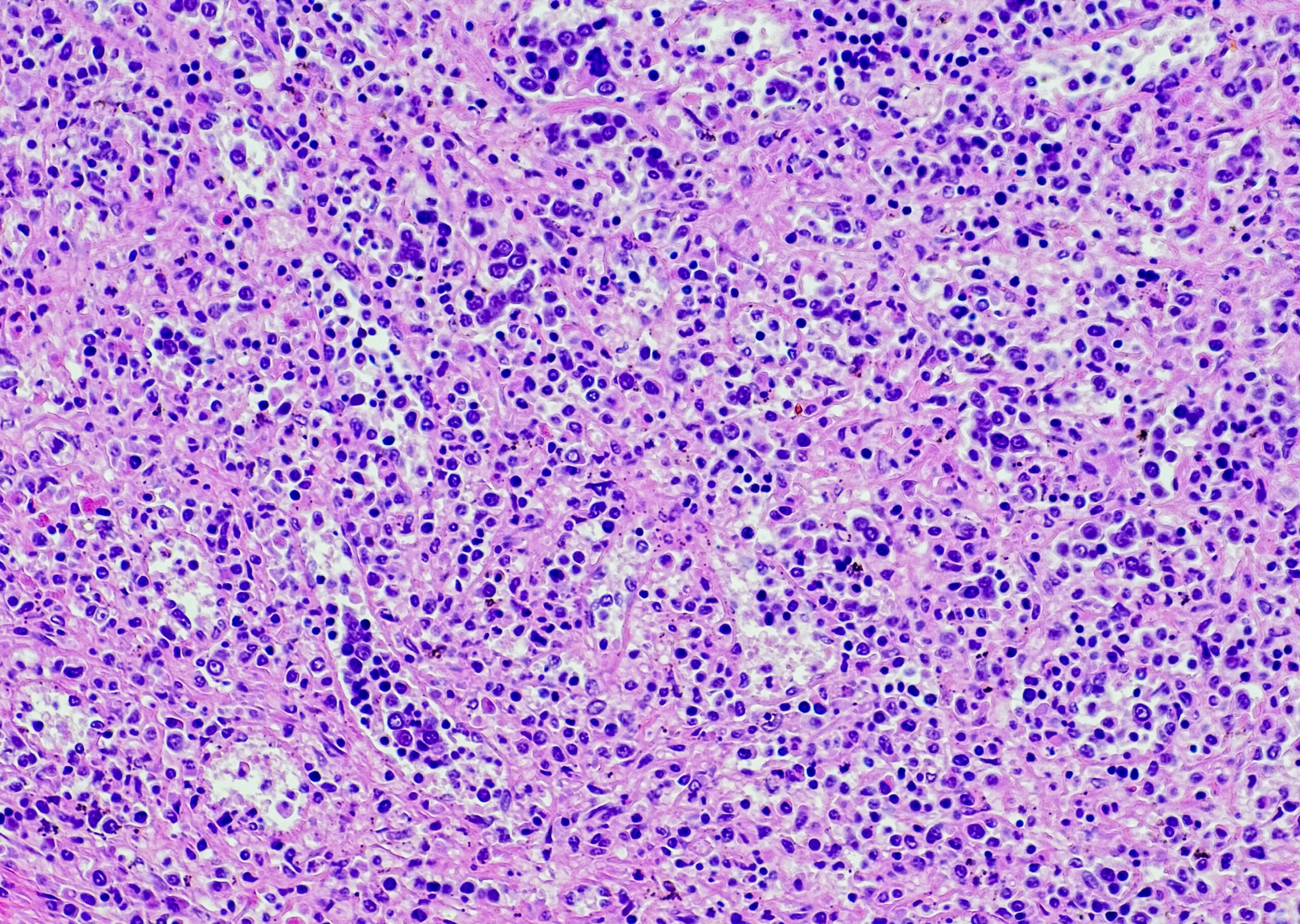

What happens to the cartilage?

Basically, cartilage plays a central role in osteoarthritis. Cartilage is a hard but at the same time elastic tissue that covers the bone extremities and ensures that the two joint surfaces can slide harmoniously against each other during movements. For various reasons such as age, obesity, damage to other joint structures (menisci, ligaments, e.g. due to excessive sports activities), malposition of the lower limbs at the hip or knee level (knock knees or knock knees) or specific diseases, microscopic cracks develop in these cartilage coatings and may gradually increase in size. Later, the cartilage tends to spall and small fragments of the joint entering the joint cavity become the cause of inflammation, thus also of pain, which maintains the vicious circle and thus promotes chronification. With progressive wear, the cartilage may even disappear completely, so that the joint bones press directly against each other. These new stresses lead to bone reactions (e.g. osteophytes, also called “ganglions”), which again aggravate the whole symptomatology, especially the pain.

Symptomatology and course

The symptoms of osteoarthritis are initially pain in and around the joints, which is predominantly load-dependent: The pain is thus worse after load than at rest, whereby an improvement is feigned, especially in the initial phase, by a supposed “warm-up”. Due to the described inflammations, effusions may occur, which are felt as swelling and deformation of the joint. Depending on the severity, stiffness also occurs.

The natural course of osteoarthritis varies from joint to joint and from person to person, but it almost always progresses, fortunately not too quickly.

Diagnostics

Precise questioning of the patient is necessary for diagnosis. Examination of the joint with associated deformities and mobility restrictions is another important step. Central, however, remains the X-ray examination, if possible in loaded form (not lying on the examination couch, but standing, exemplary for the lower extremities). MRI, which is popular today, can of course also be used. It provides information about soft tissues that are not visible in the X-ray.

And what can be done about it?

Contrary to many statements, osteoarthritis is a treatable condition. A rough distinction is made between conservative non-surgical and surgical treatment measures.

Non-surgical measures that are most commonly used, at least in the early stages, include drug and non-drug treatments. In the case of the latter, we would like to make special mention of muscular guidance, stabilization and cushioning of the joints for those who are active in sports. It has been proven many times that joints that have good muscular control basically develop less osteoarthritis. However, those already affected by osteoarthritis can also benefit greatly from physiotherapy with muscle training. Patients can learn joint-specific gymnastics programs from experienced physiotherapists and perform them independently at home without effort, but with appropriate discipline.

Unfortunately, it is not uncommon for these conservative treatments to be insufficient, in which case surgical intervention may be indicated. It goes without saying that these operations must be individually tailored. However, broadly speaking, the following surgical options can be distinguished:

- so-called arthroscopic joint toileting (increasingly controversial)

- Axis corrections with realignments (especially frequent in the knee joint)

- Joint prostheses.

Joint lavage

Arthroscopic joint lavage is a cleaning of the joint in which the various affected irregularities of the cartilage coatings and other joint structures are smoothed out and restored to some extent. At the same time, the joint is also flushed free of the various abrasions that have accumulated. In not too advanced forms of osteoarthritis, such relatively safe and not too costly operations can lead to temporary improvement.

Axis corrections with conversions

In the case of axis corrections and realignments, which are still very commonly performed on the knee joint, the entire leg axis is corrected by an operation involving the removal of a bone part either on the upper or lower leg in such a way that the weight is shifted to a preserved cartilage layer. Therefore, such an operation on the knee can only be performed if a part of the joint is still reasonably intact. This often happens in connection with sports injuries, e.g. of the meniscus, where usually only one side is affected (most often the inner side). Especially younger patients, who are basically too young for a total joint replacement, are submitted to an axis correction.

Joint replacement/prosthesis

The third option is joint replacement or prosthesis, which can be either total or hemi. Experience with this surgical technique has been gained for a good 50 years, initially in the hip area, but now frequently in the knee area, the ankle joint and the joints of the upper extremities (e.g. shoulder). The damaged parts of the joint on both joint-forming bones are removed and replaced with artificial material.

In the carefully made decision to have an artificial joint implanted, the surgeon is usually more concerned than the patient with the question: Will the prosthesis age more than the patient or vice versa? Ideally, the artificial joint will outlive the patient. The older the patient is at the time of surgery, the more achievable this goal is. Research shows that after 15 years, 90-95% of knee and hip replacements are still intact. In young active people, however, the life expectancy of prostheses is somewhat lower. The more active the prosthesis wearer is, the greater the wear of the various prosthesis parts. The material pairings used in the joints can be very different (metal, polyethylene, ceramic). The sliding of these different components on top of each other creates so-called abrasions, which are currently the biggest problem of modern artificial joints. It has been shown that up to 500,000 microparticles are abraded from the polyethylene cup in the hip joint during a single step. If you consider that a person takes about 1 million steps a year, you can well imagine that the layers sliding on top of each other become thinner and thinner and can break. This wear is of course also proportional to the forces acting on the joint. Thus, athletic stresses per se pose some risk. So the question always arises which sports are allowed or which are not. In the same breath, however, it must be noted that a loaded bone becomes more solid due to the muscular tensions that act on it, and that a well-trained musculature functions as a damping element. So clearly a reasonable compromise needs to be found.

Various studies have shown that sports with weight-bearing rotational movements, with uncontrolled movement sequences (acceleration, braking, rapid changes of direction), with strong axial loads (during landing after jumps) and with rapid strong tightening of the splayed leg are rather unfavorable. In these studies, cross-country skiing or even alpine skiing are considered possible for skilled people.

It can be stated without further ado that certain sporting activities are still possible even after the installation of an artificial joint. However, everything is a question of moderation and must be well discussed with the surgeon. As usual, a well-built, seriously executed rehabilitation is the best guarantee against early loosening or excessive abrasion.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2016; 11(1): 4-5