Headache is the second most common cause of pain worldwide [1]. Three billion people are affected every year and often the diagnosis of the different types of headaches causes headaches even for the therapists. Dr. Uwe Pohl, senior physician at the Neuromuscular Center of the University Hospital Zurich, and head of the headache consultation there, explains how to track down the pain [2].

When diagnosing headaches, a division into primary and secondary headaches has proven useful, as the therapies are also very different. Primary headache is an expression of a persistent tendency to headache of the same or similar phenotype, even in the absence of a trigger and therefore usually recurrent. Triggers such as stress, sleep deprivation, or bright lights can have an impact on pain propensity, but do not trigger the pain itself. They usually occupy therapists for a long period of time. The challenge with this type of headache is to prevent the pain from recurring.

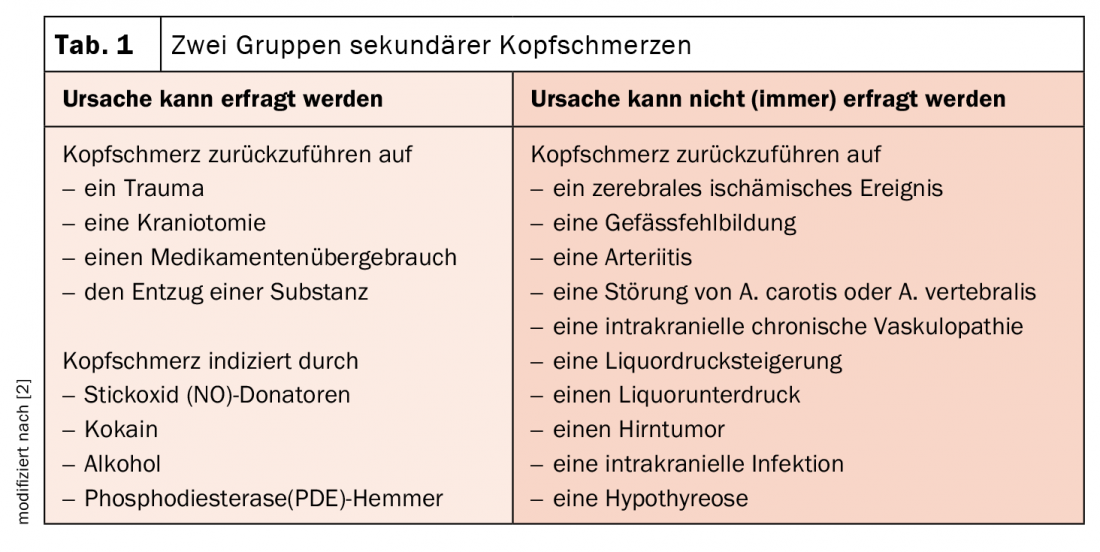

Secondary headaches, on the other hand, have a sine qua non: a potentially preventable cause without which the pain would never have occurred. Triggers in this type of headache act directly on the receptors and trigger the pain itself. These quickly subside when the cause no longer exists. Therefore, the top priority here is to find the cause of pain. However, this cannot always be requested from the patient. Therefore, a further classification into inquirable and non-inquirable causes is useful (Tab. 1).

Step by step to the correct diagnosis

Dr. Pohl recommends a systematic approach in 4-5 steps:

- Inquire about phenotype, as this is how primary headaches are distinguished.

- Inquire about possible triggers of secondary headaches, as these are differentiated according to their cause.

- Query red flags to find evidence of a secondary headache that the patient cannot recognize as such.

- Check neuro status. Only when one of the four points suggests that it may be a secondary headache does the final step occur:

- Arrange for additional examinations. Basically, the expert encourages a “hypothesis-driven anamnesis”: As soon as one suspects a certain type of headache, one should also ask specifically in this direction. In this regard, he said, it is the therapist’s responsibility to obtain the necessary information. Sufficient time and assistance are needed to obtain important and correct statements in the complicated communication with patients. Dr. Pohl cited an illustrative case from his office hours:

The patient is asked whether he is particularly sensitive to light during pain (“no”) and whether he then tends to stay in a light or a dark room (“of course in a dark room”). Also the question what the patient does during an attack (“take medication”) or whether there is any special behavior (“no”) only gets the right statement by the further assistance whether the patient perhaps lies down (“Yes of course, everybody does that, that is clear”).

|

Headache after mRNA vaccination? For the treatment of vaccine-associated tension headache, Dr. Pohl advises distinguishing between the following: Vaccine-associated headache typically occurs directly on the day or day after vaccination and, as the body’s inflammatory response to vaccination, can be treated well with NSAIDs such as ibuprofen. If pain occurs 5-7 days after vaccination, imaging is advised to rule out cerebral venous thrombosis. If the pain persists, cortisone might help; otherwise, one would further classify by phenotypes. |

Recognize the most common phenotypes of primary headache

Migraine: It affects about 20% of the female population and about 10% of the male population. It is characterized by its five main symptoms sensitivity to light and sound, nausea/vomiting, fatigue, even more frequently: need to withdraw, and by a repetitive sequence: prodromal symptoms with foodcraving (hence chocolate’s bad reputation as a migraine trigger), fatigue, onset of sensitivity to light, sound and smell, sometimes followed by urinary urgency or retention. In some patients, this is followed by the aura, after which the pain phase with the pronounced main symptoms sets in. The untreated migraine often goes into a deep sleep afterwards, and the pain subsides. But: symptoms continue to be present in this final stage, often not perceived or recognized as such by patients. Ask about fatigue, tiredness, irritability, and also euphoria or increased urination after the headache [3].

The aura lasts for a minimum of 5 and a maximum of 60 minutes. It is triggered by a wave of depolarization that propagates across the cortex and leads to different and, crucially, changing perceptual disturbances during onset, such as fortifications, tingling paresthesias, speech disorders, or dizziness [4].

Cluster headache: The second phenotype affects 0.04% to 0.4% of the population, men twice as often as women. It is characterized by its extreme pain intensity (“suicide headache”) and always occurs strictly unilaterally. The sides can change, but are never affected at the same time. Attacks occur episodically over 6-8 weeks, occurring up to 7-8 times per day with a duration of 15 to 180 minutes, averaging 1-1.5 hours if untreated. They occur primarily at night, peaking at 1 a.m., slightly earlier in women. After such an episode, a long break occurs, which can last for a year, but also for life. An accumulation in spring and autumn can be observed.

A special feature are the autonomic (also strictly unilateral) phenomena: tearing and nasal running, behind which stands the trigemino-autonomic reflex, known e.g. from eyebrow plucking. This can possibly be therapeutically influenced with triptans and oxygen, most likely these slow down the reflex. This is because it is assumed that the reflex, once triggered, causes the pain threshold to drop further and further, thus making the pain stronger and stronger. Patients accordingly report pain attacks that become more intense during 6-8 minutes and then reach a plateau where they remain for the time being. Another indication is Horner’s syndrome, presumably triggered by pressure on the ophtalmic artery and possibly on the internal carotid artery, resulting in a lesion of autonomic fibers and causing transient or permanent miosis and/or ptosis. Lipedema and unilateral sweating of the forehead also occur.

What clearly distinguishes sufferers from migraine patients is their severe restlessness. This can manifest itself in repetitive motion, aggression, or massive self-injury. An exceptional group of patients lies down despite restlessness. These often respond particularly well to indomethacin.

Tension headache: Most people are familiar with this pain, which is called “featureless headache” because of its lack of accompanying symptoms. The head feels like it is clamped in a vice. The pain is pressing, non-pulsating, mild to moderate in intensity, and is not aggravated by physical activity. Photophobia or phonophobia occur singly, if at all. Differentially, craniomandibular dysfunction (teeth grinding) should be considered, which can be recognized, for example, by clearly visible tooth marks on the edge of the tongue.

Narrow down secondary headaches further with Red Flags

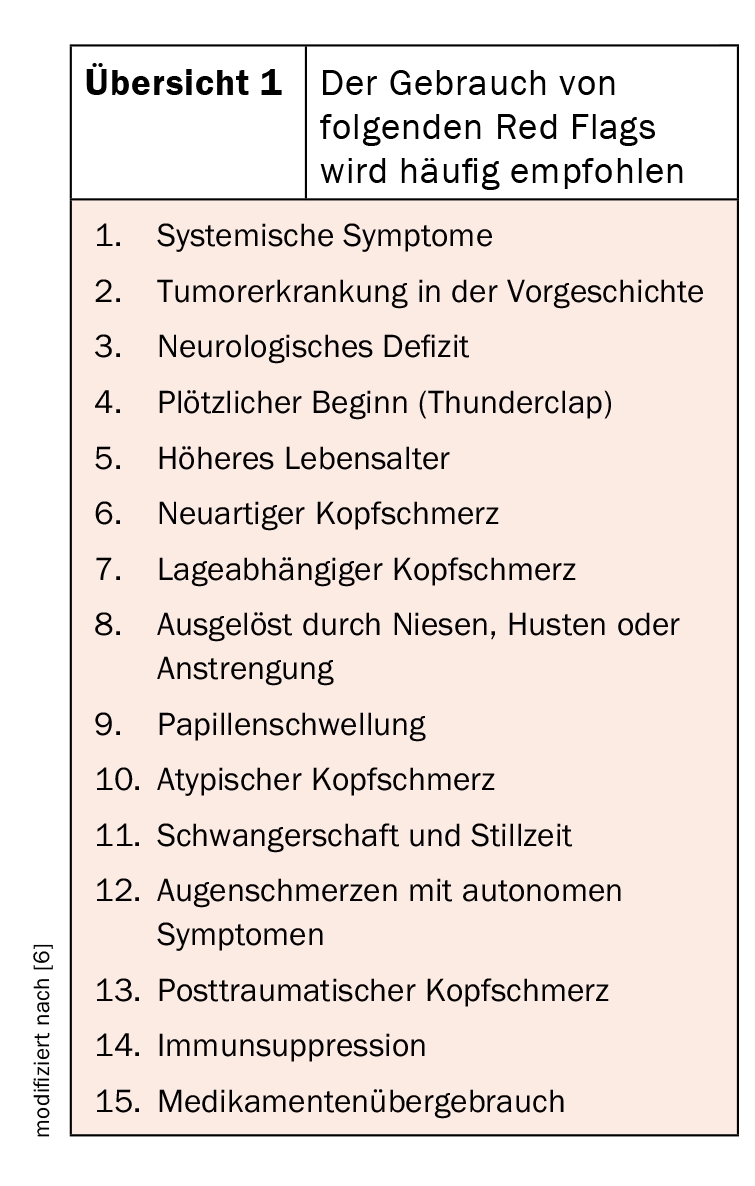

If, after careful history taking and examination, it remains unclear whether the headache is secondary, the so-called red flags are used. Like a screening test, they provide information on whether there is a high probability of a secondary headache and whether additional examinations are necessary. In patients with headache of unexplained cause, a sign or symptom is a red flag if the secondary headache is more likely to occur with that red flag than without it [5].

However, according to Dr. Pohl, the list of red flags (overview 1) should be used with caution; there are too few studies on it, and most of the points are merely eminence-based. Risk factors such as items 2, 5, 11 or 14 say only something about the pretest probability but nothing about the headache being sought and thus have the least significance. However, symptoms of diseases that in turn trigger secondary headaches are different – these are the ones to watch out for. These include items 1, 7, 8, 9 and 12.

Systemic symptoms (1) include mainly fever, also a neurological deficit, especially when this is fresh. Positional headache (7) may be due to CSF over- or under-pressure. Headaches (8) triggered by sneezing, coughing or exertion may have their origin in pathologies of the posterior fossa. In case of repeated eye pain with autonomic symptoms (12) you should rightly also think of cluster headache, but at the first occurrence you should also think of glaucoma. This typically exhibits a dilated pupil during pain, and a constricted pupil during cluster headache (Horner). If there is no pain during the consultation, you should ask the ophthalmologist for pressure clarification. Medication overuse (15), novel (6) or atypical (10) headache do not help in selecting necessary additional investigations.

Take-Home Messages

- Whenever you find a symptom that cannot be explained by the headache, arrange for additional tests.

- The anamnesis is of the greatest importance in headaches.

- Primary headaches are differentiated according to their phenotype.

- Secondary headaches are due to a separate cause.

- Keep in mind that patients are not always aware of these causes. In such cases, the Red Flags can help.

Literature:

- GBD 2017 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators: Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 2018; 392: 1789-1858; doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32279-7.

- WebUp Expert Forum “Update Neurology”, 06.04.2022.

- Blau JN: Migraine: theories of pathogenesis. Lancet 1992; 339: 1202-1207; doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)91140-4.

- Pietrobon D, Moskowitz MA: Pathophysiology of Migraine. Annu Rev Physiol 2013; 75: 365-391; doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-030212-183717.

- Pohl H: Red flags in headache care. Headache 2022; doi: 10. 1111/head.14273.

- Do TP, Remmers A, Schytz HW, et al: Red and orange flags for secondary headaches in clinical practice: SNNOOP10 list. Neurology 2019; 92(3): 134-144; doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000006697.

InFo PAIN & GERIATry 2022; 4(1-2): 30-31.