In Switzerland, paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and metamizole are available as non-opioid analgesics. NSAIDs or metamizole should be considered if acetaminophen does not provide adequate pain relief. A differentiated consideration of the efficacy to be expected in relation to possible dose-dependent side effects is recommended, with patient education playing an important role.

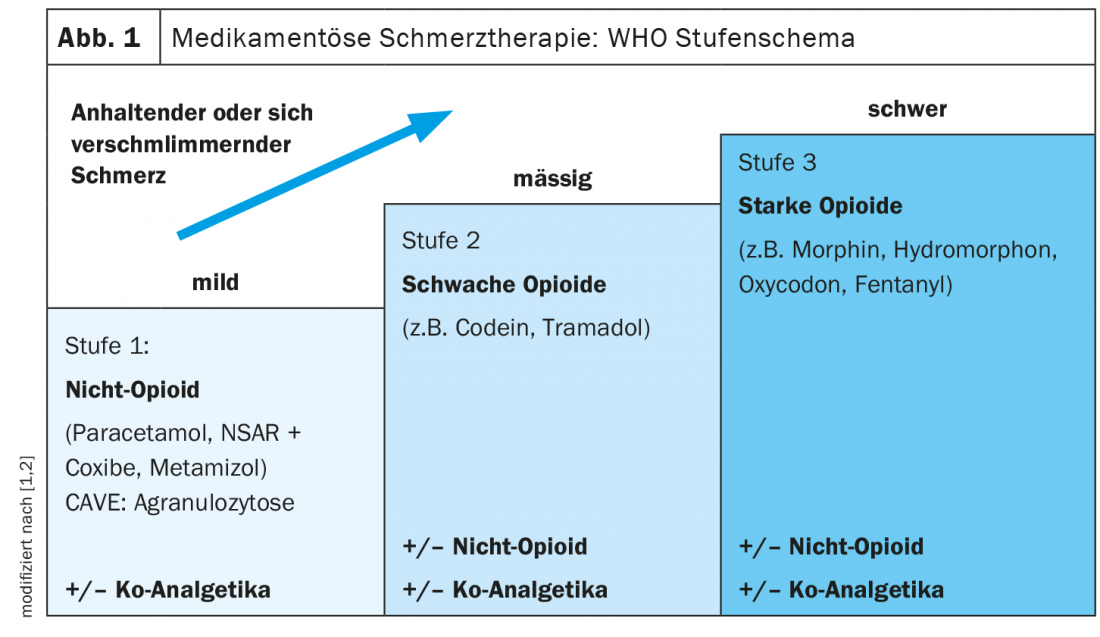

In the WHO staging scheme for the treatment of non-oncologic pain, non-opioids are ranked at level 1 (Fig. 1). [1]. For back pain, the first choice is generally paracetamol, according to Prof. Matthias Liechti, MD, Deputy Chief of Clinical Pharmacology, University Hospital Basel [2]. If pain relief is insufficient, consider switching to metamizole or a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID), the speaker said [2,3]. If necessary, metamizole (e.g. Novalgin®) or an NSAID (e.g. ibuprofen or diclofenac) can also be used as an add-on. Metamizole is an active ingredient from the pyrazolone group with analgesic, antipyretic, and spasmolytic properties [4]. The exact mechanism of action is not known. Inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis by COX-1 and COX-2 inhibition is thought to contribute to the analgesic effect [2]. “It is more effective than paracetamol and equally effective as NSAIDs,” says Prof. Liechti, summarizing the analgesic effect of metamizole [2,4]. This is confirmed by a Cochrane review by Moore et al. in which the number needed to treat to achieve a pain reduction of 50% was compared for various analgesics [6]. Paracetamol had a higher NNT compared to NSAIDs or metamizole in this secondary analysis, thus proved to be inferior in terms of efficacy. Opioids are ranked at levels 2 and 3 in the WHO regimen. Opioid analgesics have a strong analgesic effect, but also a high dependence potential.

Non-opioids for the treatment of movement-related pain.

There are other reasons for avoiding opioids in the treatment of chronic back, knee, or hip pain besides the risk of addiction: a controlled-randomized study published in 2018 found that comparatively lower pain intensity was achieved under non-opioids [2,7]. This can be explained by the fact that opioids can be given at high doses for short periods in hospitalized patients, whereas this is hardly possible in outpatients. A secondary analysis by da Costa et al. on the efficacy of various analgesics for motion-related pain due to knee or hip osteoarthritis showed that NSAIDs (e.g., ibuprofen or diclofenac) in the higher doses achieved a statistically and clinically relevant increase in efficacy, but: “The efficacy of NSAIDs is bought with more side effects,” according to Prof. Liechti [2,8].

Side effects of NSAIDs and metamizole compared

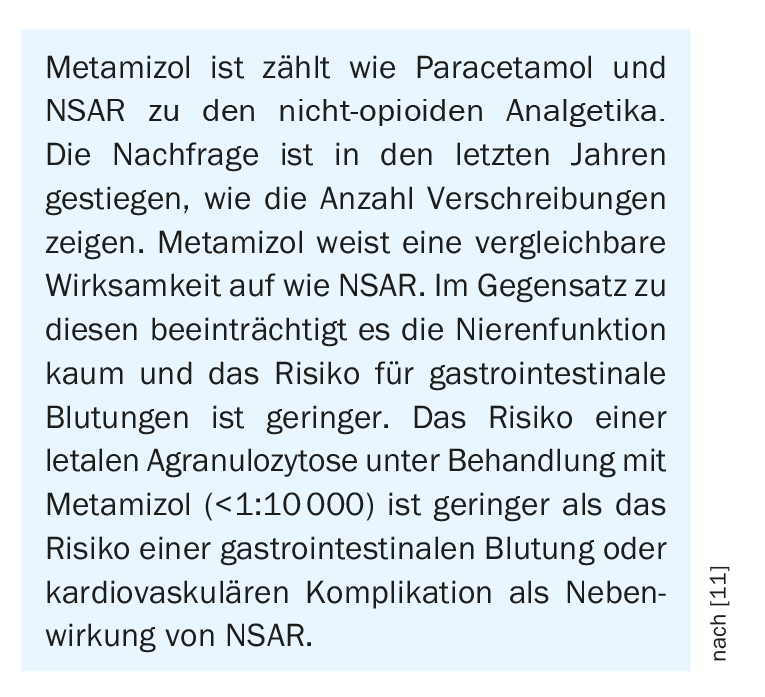

Dose-related potentially life-threatening side effects of NSAIDs include, in particular, cardiovascular problems and gastrointestinal bleeding, Prof. Liechti explained. A study analyzing mortality risks associated with short-term analgesic use indicated that the mortality rate due to gastrointestinal bleeding under diclofenac was significantly higher than that due to agranulocytosis under therapy with metamizole [9]. Although metamizole may lead to inhibition of platelet aggregation through thromboxane synthesis, the risk for the occurrence of clinically relevant bleeding is significantly lower compared with NSAIDs because metamizole at normal doses leads to less pronounced inhibition of COX-1, according to Dr. Stephen Jenkinson, head of innovations at pharmaSuisse [2]. Case-control studies show an association of metamizole and gastrointestinal bleeding, but the estimated relative risk (RR) of 1.4-2.7 is much lower than for NSAIDs (RR of 2.1-10.0) [10,11]. In contrast, with metamizole, the risk of agranulocytosis is the subject of controversy. This is a potentially life-threatening but rarely occurring complication. Estimates of the incidence of agranulocytosis with metamizole vary considerably in the literature from 1:1500 to less than one case per million uses of metamizole [11]. The elaborate Berlin Case-Control Study prospectively investigated the incidence of agranulocytosis in the greater Berlin area in a population of approximately 2.9 million individuals in 180 hospital departments [11,12]. Calculated on a one-week outpatient course of metamizole, the risk of agranulocytosis was one case per 286,000 patients.

Source: Sanofi

Literature:

- WHO Stage Scheme, www.pschyrembel.de/WHO-Stufenschema/K0PQ7, (last accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- “Recognizing and counseling acute pain patients,” webinar, Sanofi, 5/18/2022.

- Drug Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch, (last accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- Nikolova I, et al: Metamizole: A review profile of a well-known ‘forgotten’ drug. Part II: Clinical profile. Biotechnol & Biotechnol Equipment 2013; 27(2): 3605-3619.

- Polzin A, et al: Excess Mortality in Aspirin and Dipyrone (Metamizole) Co-Medicated in Patients With Cardiovascular Disease: A Nationwide Study. J Am Heart Assoc 2021; 10(22): e022299.

- Moore RA, et al: Non-prescription (OTC) oral analgesics for acute pain – an overview of Cochrane reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 2015(11): CD010794.

- DeRonne B, et al: Effect of Opioid vs Nonopioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial JAMA 2018; 319(9): 872-882.

- da Costa BR, et al: Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: a network meta-analysis. Lancet 2017 Jul 8; 390(10090):e21-e33.

- Andrade SE, Martinez C, Walker AM: Comparative safety evaluation of non-narcotic analgesics. J Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51(12): 1357-1365.

- Haschke M, Liechti ME: Metamizole: benefits and risks compared with paracetamol and NSAIDs. Switzerland Med Forum 2017; 17(48): 1067-1073.

- Andrade S, et al: Safety of metamizole: a systematic review of the literature. J Clin Pharm Ther 2016; 41(5): 459-477.

- Huber M, et al: Metamizole-induced agranulocytosis revisited: results from the prospective Berlin Case-Control Surveillance Study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol 2015; 71(2): 219-227.

- Federal Office of Public Health (FOPH), www.bag.admin.ch/bag/fr/home/medizin-und-forschung/heilmittel, (last accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- PharmaNews 08/20, www.pharmacap.ch/document/stream/44c37835628625604a1de106559bca83, (last accessed Oct. 19, 2022).

- Pharmasuisse: Facts & Figures 2016, www.pharmasuisse.org/data/docs/de/6267/Facts-and-Figures-2016.pdf?v=1.0, (last accessed Oct. 24, 2022).

- National Health Care Guideline, Non-specific Low Back Pain, 2nd edition, 2017, www.leitlinien.de/themen/kreuzschmerz, (last accessed Oct. 24, 2022).

- Babej-Dölle R, et al: Parenteral dipyrone versus diclofenac and placebo in patients with acute lumbago or sciatic pain: randomized observer-blind multicenter study. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther 1994; 32(4): 204-209.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(11): 32-33