The wave of opioid prescriptions in the U.S., but also in Switzerland, has problematic consequences. Among other things, the preparations can be highly addictive. So what does responsible use of highly potent drugs look like today?

If opioids are used in the acute pain situation, they have side effects such as nausea, vomiting, sedation, respiratory depression, constipation, etc. In the long term, i.e. in chronic pain, they are generally well tolerated, but are only considered as a therapeutic option in about half of patients and only at low doses. This is due to possible long-term side effects such as the development of tolerance or hypogonadism (particularly relevant in young patients) and above all – as has become clear in recent years – the problem of addiction if used incorrectly.

As a reminder, heroin, which is known to be highly addictive, is a highly analgesic opioid. It is therefore not surprising that other opioids from the medical field – especially if they are short-acting and dock extremely quickly to the receptors – also bring with them a high potential for addiction. In America, especially the oxycodone was dangerous, which was very easy to bite (in the meantime, the company changed the structure of the tablet to a gel-like form), which led to an abrupt effect. The same is true for opioid drops. The effect is partly comparable to a (heroin) injection. In the USA, where such preparations had been freely prescribed for years, the problem became increasingly evident: “Oxys” suddenly became ubiquitous, crushed and snorted (“flushed”), users changed doctors at will to get prescriptions easily, or even switched to heroin (because it is cheaper). Once a high dosage was established, the addiction – driven by freedom from pain, an extraordinarily strong reward effect, and an all-encompassing high – was already so central that it was almost impossible to think about reducing the dosage or stopping.

And Switzerland?

Now, one might think that the problem is a “homegrown” U.S. one. In fact, Switzerland is not comparable to American conditions. Nevertheless, the rapid growth of opioid use in this country since the 1980s and 1990s deserves attention. Switzerland is one of the ten countries with the highest opioid consumption; every fifth pain patient under drug therapy is treated with an opioid. What does the increase have to do with?

The extension of the indication to non-tumor patients 25 years ago as well as the old doctrine that freedom from pain is a human right or medical duty (keyword: “pain-free hospital”) and opioids must be increased until the pain is treated certainly contributed to this. It was assumed that opioids were largely harmless and that dose increases were therefore unproblematic, with minimal, if any, risk of addiction. Patient education left much to be desired, opioids were not “last resort” but were overpromoted by the pharmaceutical industry to physicians and the general public. Patients with postoperative pain came from hospitals on high doses, and after discharge there was no tapering off; on the contrary, there was often even a dose escalation. In addition, there is a lack of unproblematic, good drug alternatives for long-term use.

Consequences of widespread high-dose opioid therapy were an increased risk of mortality (confirmed in the USA), an insufficient effect, increasing concerns about unfavorable long-term side effects, and the impossibility of reducing the dose again (unmotivated or already addicted patients: “everything else is useless”). In addition, “Stage 4” was now missing, there was no further escalation stage. Patients had long since stopped taking opioid painkillers (only) for pain relief. Some couldn’t even start the day without the energy and high from the medication.

Principles

Warning signs of opioid dependence may include:

- Difficulties in the private or work environment

- Missed deadlines

- Prescriptions by different doctors

- Losing recipes

- Decrease in analgesic effect

- Aggressive behavior (“You don’t understand my pain at all!”)

- Independent dose increase

- Preference for short-acting opioids.

- Frequent changes of doctors

- Positive urine test for other substances.

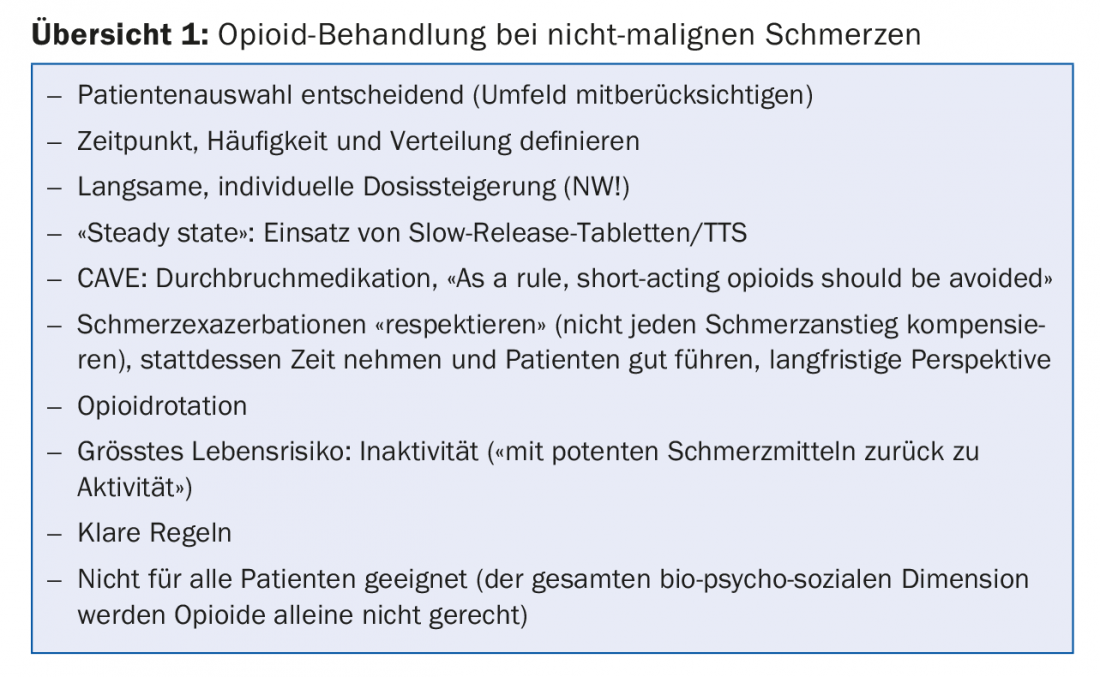

“Therefore, don’t let it happen in the first place,” the speaker warned the audience. “Be very careful with short-acting or parenteral forms (reserved for tumor patients, but extremely important here). The same applies to psychiatric comorbidities such as borderline personality disorders. Define clear rules for patients at medium to high risk of dependence, educate them carefully, agree on an upper dose limit and therapy goals. Monitor these consistently, give limited prescriptions (and/or supervised dispensing), favor lower dependence potential formulations and weak over strong opioids, rotate in low doses. Parallel mental health support may be useful.” Ultimately, the goal of pain reduction in non-tumor patients is to return them to activity. Otherwise, they lose muscles, fall and suffer a whole cascade of consequences (such as fractures, etc.). Overview 1 summarizes the principles of opioid therapy once again.

Short-acting forms (preferably preparations with retarded galenics), “uncontrolled” or “uncritical” delivery or dose increase and, of course, long-term development of tolerance (rotation, intermittent discontinuation, etc. help) should be avoided.

Interventions with already addicted people

Switching in patients who already show symptoms of dependence on prescription opioids is very difficult. In cases of conspicuous dependence, a gradual reduction of the dose can be attempted, but with high relapse rates. It is possible that concomitant therapy may prove helpful (e.g., administration of clonidine). Opioid rotation and substitution are also conceivable. Buprenorphine, for example, occupies 95% of opioid receptors at the dose of 16 mg and has a potent analgesic effect (not approved for pain management) and a “ceiling effect” on respiratory depression.

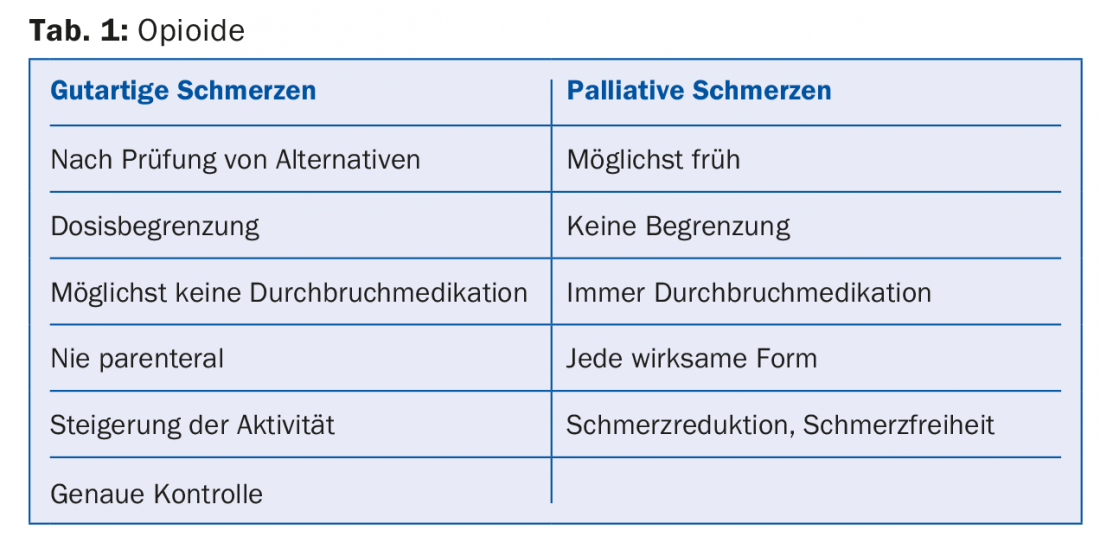

Finally, it should be mentioned that different rules apply to the therapy of palliative pain than to benign pain. Table 1 shows a comparison.

Source: VZI Symposium, January 25, 2018, Zurich

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(2): 34-36