Headaches and facial pain are among the most common complaints, which is why patients seek medical consultation. An observational study in 2000 showed that headache was reported as the chief complaint in nearly 10% of primary care consultations. Only 6% of men and 1% of women have never experienced headaches in their lives.

Headache and facial pain, along with back pain, are among the most common complaints for which patients seek medical consultation [1]. An observational study in 2000 showed that headache was reported as the chief complaint in nearly 10% of primary care consultations [2]. Only 6% of men and 1% of women have never experienced headaches in their lifetime [3]. It is worth noting that a wide range of pathologies can manifest as headache or facial pain. In addition to neurological disease patterns, pathologies from various other specialties, such as dentistry, otorhinolaryngology, angiology, or rheumatology, must also be considered in the differential diagnosis.

Medical history

Basically, the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD-3) distinguishes primary from secondary headaches and from neuralgias in three chapters. Primary headache is defined or characterized by the absence of a demonstrable etiology [4]. Accordingly, from a clinical point of view, the history plays a central role in the diagnosis, whereas the examination is of little importance due to the absence of detectable pathologies. This applies analogously to idiopathic neuralgias. Among other things, the initial onset, duration, time pattern, quality, triggers and modulators, as well as previous diagnosis and therapy are elicited.

Since the general health and psychosocial contextual factors can significantly influence both the onset of the complaints and their course and prognosis, they should be discussed in detail with the affected person from the outset. When reflecting on the psychosocial aspects, a respectful attitude, guarantee of privacy and sufficient time are required [5].

Contextual factors should be inquired about as part of a multimodal assessment in the psychosocial history interview prior to biofeedback treatment. A suitable basis is formed by information from different questionnaires for the recording of orofacial complaints as well as further evaluation instruments. Pain drawings provide an initial overview of the localization, spread and intensity of pain. Clues to pain patterns and parafunctions (e.g., teeth grinding, lip and cheek biting, tongue clenching) or modulators (e.g., chewing hard foods, mental stress, high emotionality) provide symptom-based checklists. Questionnaires for somatic complaints (Patient Health Questionnaire 15; PHQ-15) and the Symptom Questionnaire for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC-TMD) are suitable. The Patient Health Questionnaire 4 (PHQ-4) provides indications for depression and anxiety, and the PHQ stress module for psychosocial stress.

The preliminary findings obtained form a suitable basis for the psychosocial history interview [6]. The weighting of complaints and the influence of associated contextual factors become clear. Stress from work and relationships can provide a stressful life context with worry and anxiety. Accordingly, the pain picture presented is to be classified and interpreted holistically under the triad of symptom, conflict and biography. Specific correlations between the complaints and the temporal perspective of their occurrence become apparent. In many cases, the conversation also reveals that although the causes of the pain are not clear, emotions have a significant influence.

Clinical examination and imaging

The history and available previous findings allow a tentative or differential diagnosis. For secondary headache and facial pain, careful clinical assessment is used to assign pain to pathologies in specific tissues. Regarding imaging, two aspects have to be considered: First, the possibilities to visualize microstructural processes involved in pain genesis are still limited with current imaging methods. Second, the extent of structural changes does not necessarily correlate with the pain complained of [7]. Chapter 11 of ICHD-3 lists potential causes in different tissues of secondary headache: Diseases of the skull and of the neck, eyes, ears, nose, sinuses, teeth, mouth, and other facial or cranial structures [4].

The temporal relationship between the first occurrence of a new headache or the worsening of a pre-existing headache (usually defined as at least a twofold increase in frequency and/or severity) and disease of one of the above structures should be evaluated. Usually, a lesion can be detected clinically, by laboratory chemistry, and/or by imaging.

The clinical findings already start during the anamnesis. Posture, gait, general motor unsteadiness (hands, fingers, lower extremities), facial muscle tone (facial expressions, resting position of the lower jaw, lip biting, fingernail biting, gum chewing), and facial symmetry (swelling, tissue defects, thickening of cranial vessels) are observed.

For diagnostic purposes, patients are placed in an upright position so that free head movement in all directions remains possible. Patients should be informed in advance that the examination is aimed at identifying the causes of pain and may therefore be painful.

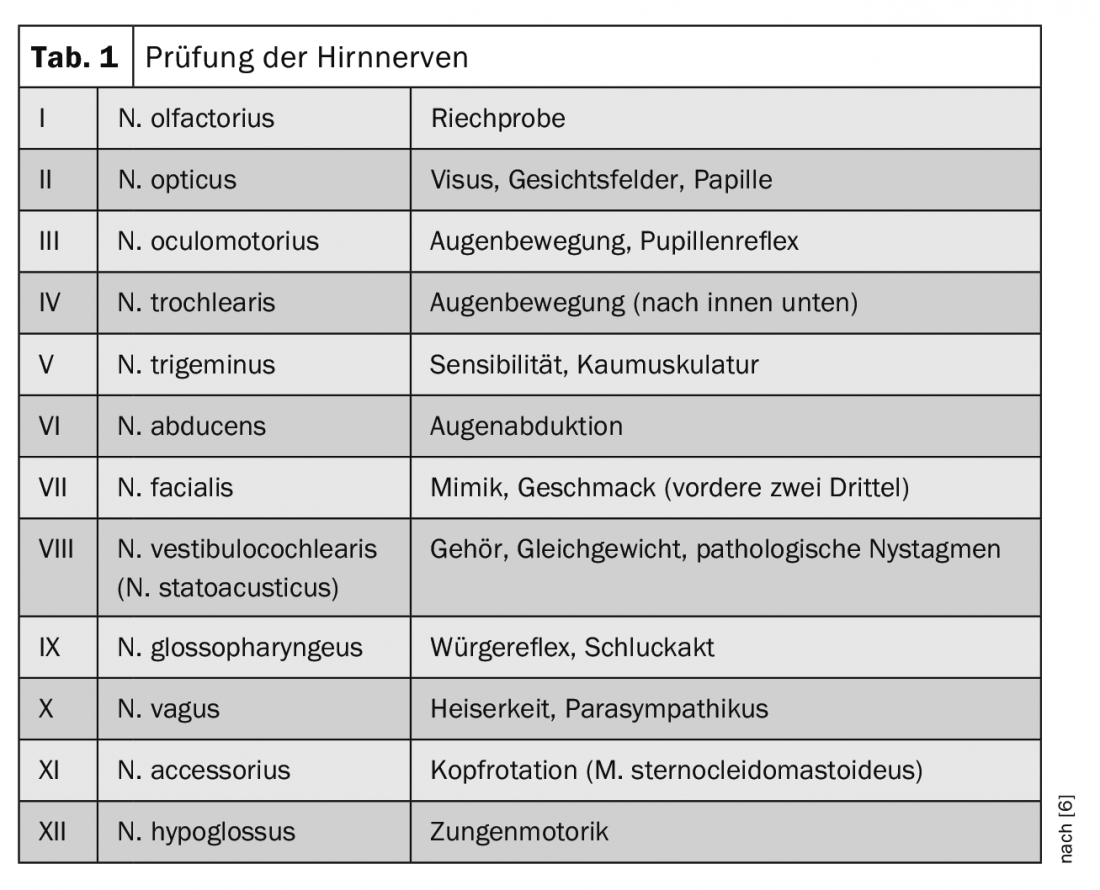

Palpation of the sub- and retromandibular region as well as of the neck reveals any swelling and, if necessary, hardening of the lymph nodes. This is especially important to note in cases of dysphagia, as it may be an indication of malignant processes in the face/mouth/throat area. This is followed by an examination of the cranial nerves as needed (Tab. 1) . In the case of facial pain, special focus is placed on the function of the trigeminal nerve (N.V), since it sensory innervates the entire face with the exception of the jaw angle (fibers from the cervical plexus C2). Negative (hypesthesias, hypalgesias, anesthesias) and positive (paresthesias, dysesthesias, allodynia) sensory symptoms are recorded. Medical help is sought mainly because of the painful symptoms. An injury, possibly a dysfunction of the weak or unmyelinated fibers (thin fibers, A-delta, C-fibers) can be primarily assessed by means of bedside tests (such as PinPrick test). If necessary, so-called quantitative sensory testing (QST) provides accurate information about the extent of nerve pathology. During a QST, detection thresholds as well as pain thresholds to thermal (cold, heat, warmth) and mechanical stimuli (touch, vibration, pinpricks, pressure) as well as pain summation are recorded [8].

Apart from toothache, so-called temporomandibular dysfunctions, i.e. disorders of the masticatory muscles and the temporomandibular joint, are the most common cause of facial pain [9]. At the same time, they are the second most common (after lumbar spine pain) musculoskeletal condition resulting in pain and disability [10]. A standardized protocol for collecting masticatory muscle and temporomandibular joint findings and diagnostic criteria were first published in 1992 and revised in 2014. It was published under the acronym DC-TMD (diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders) [11]. The extent of the mouth opening (distance between the incisal edges of the anterior teeth) is measured with the aid of a ruler and the symmetry of the opening movement is assessed. Then the passive mouth opening is measured, i.e. the examiner supports the patient to open the mouth even wider. According to broad population studies, a minimum mouth opening is min. 35 mm and maximum deviation of the mandibular midline ≤2 mm. Finally, the mandibular advancement and lateral movements are measured (standard value ≥7 mm). Due to the large interindividual variability of jaw mobility, the measurements are mainly suitable for monitoring the course and less as absolute criteria for diagnosis. In each case, it is noted whether the jaw movements are painful, where the pain is localized, and whether the examination pain corresponds to the complaints made. Inquiries are made about noises during jaw movements, the type of noise (cracking, rubbing) and whether pain is associated with the noises. Temporomandibular joint sounds can also be auscultated using a stethoscope. Jaw opening blockages and locks (difficulty in closing the mouth) are also documented.

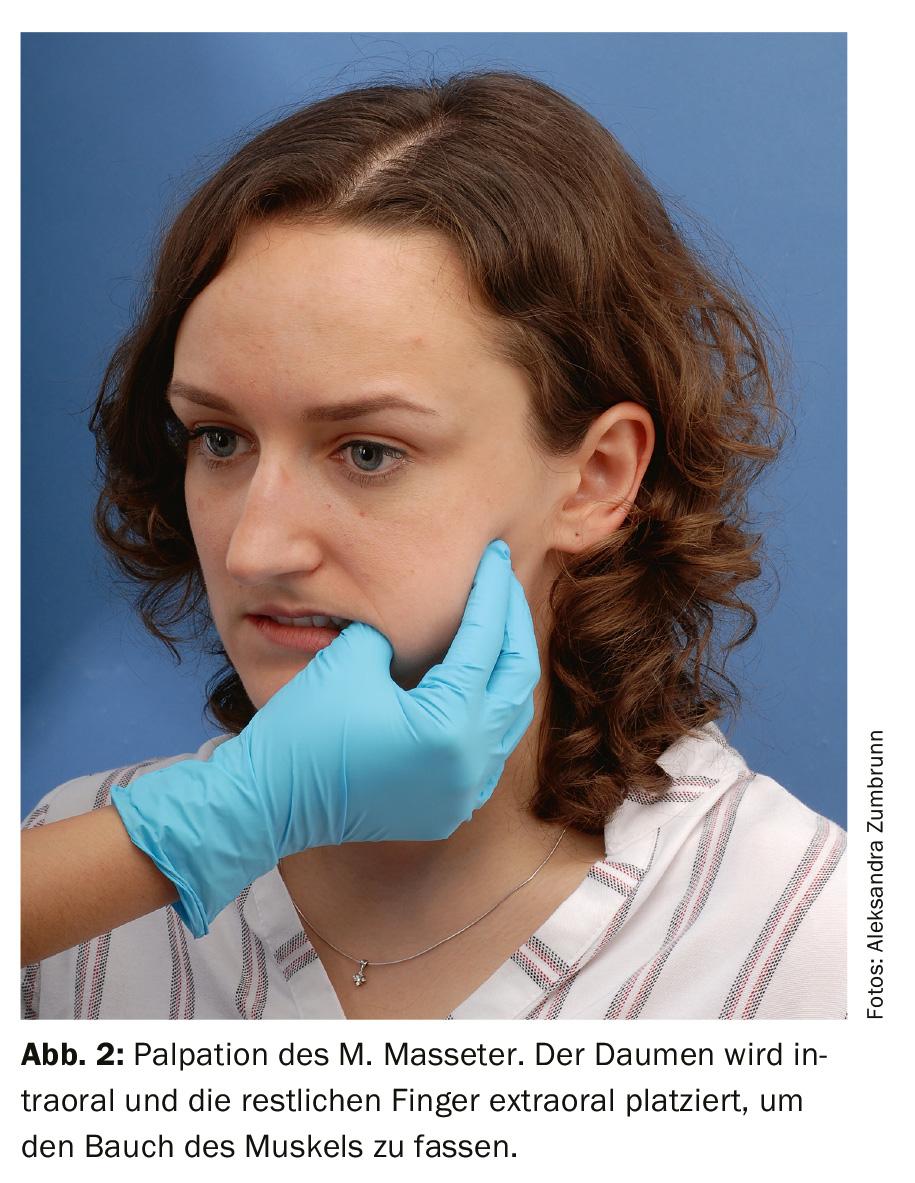

Movement measurements are followed by palpation of the masticatory muscles to identify the tissue origin of the complained pain. If the examination provokes pain, the patient is asked whether the pain is limited to the palpated area or whether it radiates to other structures (e.g., eye, ear, teeth). The masseter muscle and the parts of the temporalis muscle along the temple are palpated. According to DC-TMD specifications, a pressure of min. 1 kg for at least 5 seconds to provoke possible pain transmission to distant structures. The temporomandibular joints are palpated from the outside in a comparable manner, but with a reduced pressure of 0.5 kg. Finally, the retromandibular and submandibular muscles (floor of the mouth) as well as the intraoral muscles are palpated (lateral pterygoid muscle and attachment of the temporalis muscle to the coronoid muscle). For the lateral pterygoid muscle, palpation is performed behind the maxillary tuberosity with the patient pushing the mandible in the ipsilateral direction to create enough space for palpation (Fig. 1).

The coronoid process is best palpated intraorally with the mouth wide open.

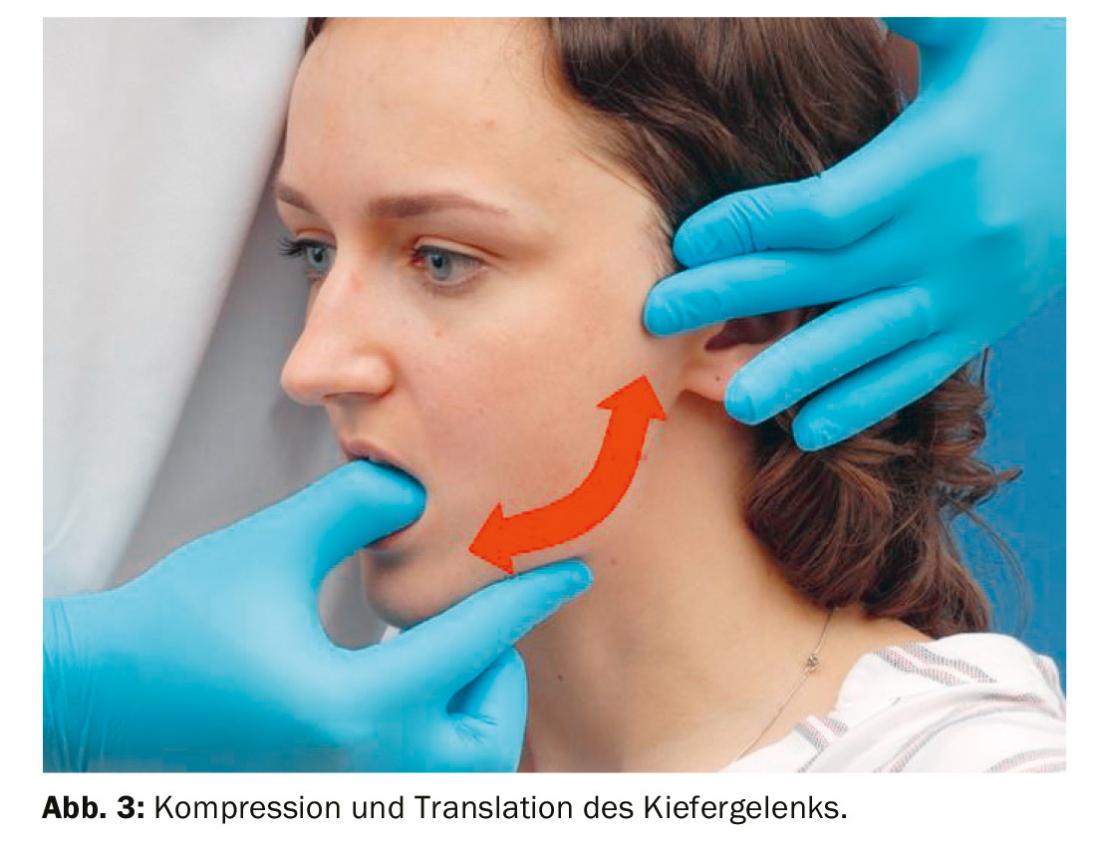

In addition to the examination steps of the DC-TMD guidelines, bidigital palpation of masseter’s disease (thumb intraoral, remaining fingers extraoral) has proven to be effective. (Fig.2) as well as the passive, forced compression and translation of the temporomandibular joints proved to be helpful for the diagnostic procedure (Fig.3). While one hand is used to stabilize the skull and palpate the temporomandibular joint, the free hand is used to guide the mandibular body cranially (compression) or ventrocaudally (translation/traction). Compression pain typically indicates active, erosive TMJ inflammation, whereas translational pain is more characteristic of discopathies. TMJ pain is often accompanied by myalgia of the masseter muscles and radiates to both the mandible and maxilla (sometimes extending to the eye). Anamnestically, patients often report an increase in pain intensity when chewing hard foods for both muscular and articular pain etiology. From the age of 50, a giant cell arteritis with the leading symptom of so-called claudication masticatoria should be considered as a differential diagnosis. The diagnosis should be extended to include measurement of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

During the intraoral examination, swelling, redness, fistulas as well as pain at the alveolar ridge indicate a dental cause of pain. Bite, percussion and possibly pressure pain are typical of acute inflammation in the region of the tooth root tips. Grinding marks on the teeth as well as changes in the buccal mucosa (so-called intercalary line) and tongue indentations are often signs of parafunctions in the sense of teeth clenching/grinding or tongue pressing as well as lip biting. Oral parafunctions, as well as daily gum chewing or nail biting, can cause myogenic headaches that resemble tension-type headaches [12]. Furthermore, enamel cracks and grinding marks caused by the parafunctions can lead to hypersensitivity to cold, heat or acid, which patients describe as “enclosing”, “piercing” and “attack-like”. Differentiation from trigeminal neuralgia can be challenging.

Relationship between stress load, muscle tone, pain

Few people are aware of oral parafunctions. Therefore, reproduction of the complained pain during the clinical examination often serves patients as the first clue to a muscular complaint etiology. Masticatory muscle pain lends itself to addressing unconscious muscle tension in the context of stressful situations. Accordingly, the reference to persistent changes in tone during negative emotional states forms a bridge to the thematization of the bio-psycho-social model. Demonstration of the painful masseter muscle in the temporal region facilitates understanding of the relationship between stress and headaches. In addition, there is often tension in the shoulder and neck muscles and, at most, temporomandibular joint complaints (noises, mouth opening restriction, arthralgia). Sufferers can be told that feelings of being overwhelmed, loss of control, or fears of pressure to succeed inhibit the ability to relax. Then, techniques for promoting the ability to relax can be presented. Often, learning an easy-to-implement relaxation method, preferably Jacobson’s Progressive Muscle Relaxation, already helps. Relief of the masticatory system is possible via learning improved body awareness with a loose lower jaw posture. When available, biofeedback is a helpful adjunct to therapy, especially for persistent headaches and facial pain.

Information dissemination

At the beginning of a biofeedback treatment, information is provided [13]. The patient is informed about the course of treatment, the theoretical background and the derived bodily functions. A psychophysiological explanatory model is to be worked out. Diagnostically clarified is the increased muscular tension in the jaw and facial musculature. Relationships between muscle tension, stress, and perceived head and facial pain are recorded. Suitable parameters include EMG, temperature, skin conductance, and pulse and respiratory rate or amplitude. Common lead locations for EMG are the frontalis muscle, the masseter muscle, and the trapezius muscle. Emphasis is placed on the fact that the feedback of physiological parameters of muscle tension, which is often not perceived accurately, is aimed at consciously perceiving muscle activity in order to then learn to reduce it in a targeted manner (Fig. 4). Improved self-control makes it possible to influence future pain episodes. This has the effect of distancing and distracting pain.

The immediate feedback demonstrates to the patient that bodily functions change depending on stress and can be positively influenced by means of relaxation and attention. This increases the self-efficacy expectation. Thus, the exercises are considered significant motivational elements for understanding pain mechanisms. The state of pain is recognized as diametrically opposed to the relaxation response. Training successes can be reported in terms of jaw relaxation in the course of the session in the form of reduced EMG activations (in µV). The value at mindful intake of a loose posture of the mandible is compared with the normal value of ≤3 µV. This corresponds to the average activation during “everyday” posture of the mandible.

Stress profile

To start a biofeedback treatment, it is suitable to create a stress profile for stress diagnostic purposes. Psycho-physiological reaction patterns can be vividly demonstrated. Stress is manifested by a reduction in peripheral and central blood flow, increased sympathetic activity, and reduced vagotone. Questions can be answered such as: Which body system reacts most clearly to psychological stress, which shows delayed recovery after a stressor, and which content elicits the strongest physiological response in the patient?

Different stress tests can be used as stressors: The ability to relax before and after a stressor can be recorded. Memory or mental arithmetic tasks (e.g., “count down from 2000 in increments of 17 as quickly as possible”), sound exposures, imagining problematic situations, and hyperventilation tests are used. The latter are used for testing behavior under stress and subsequent correction of existing false attribution of causes to organic diseases. Demonstrate how somatic complaints (e.g., tension, palpitations, dizziness) are produced by one’s own behaviors or volitional provocation.

Breathing training

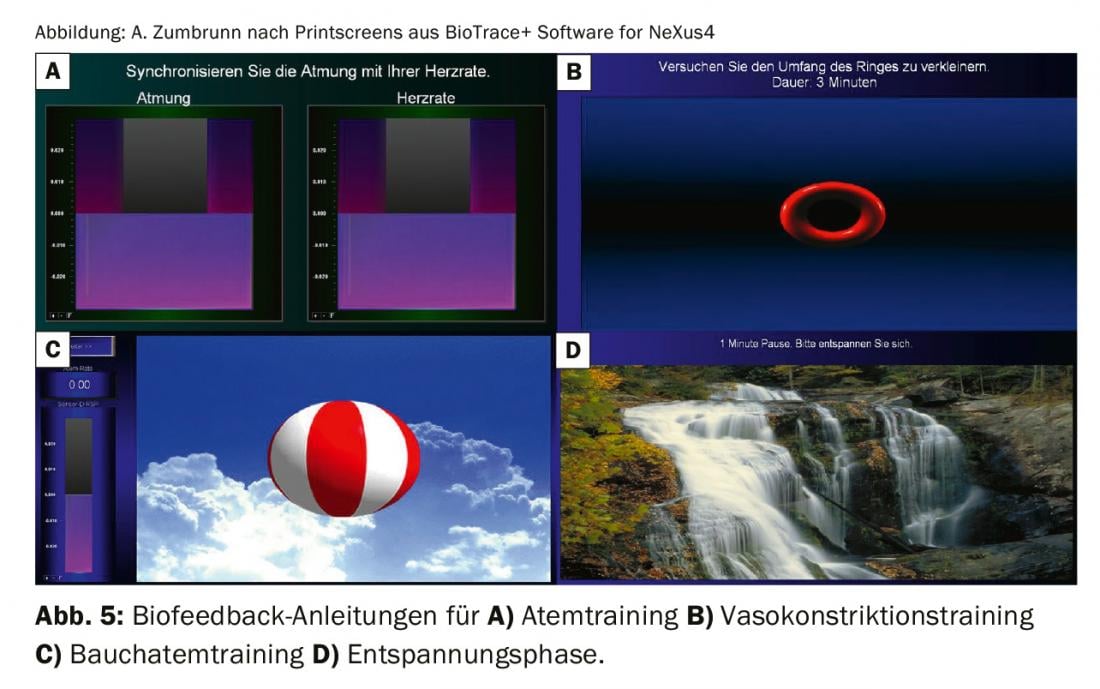

The first exercise in the biofeedback-assisted respiratory school is a demonstration of how to influence respiratory function at will. The aim of exhalation training towards a target frequency is to reduce unfavorable breathing behavior (Fig. 5) . In stressful situations, increased chest and shoulder breathing as well as an increased breathing rate with pauses in breathing that are too short or absent are characteristic. Patients are sensitized to conscious control of breathing with proper breathing technique with regard to the following aspects: Increasing breathing depth (breathing amplitude), decreasing breathing rate (below 8 puffs per minute), increasing relaxed abdominal breathing while reducing chest and shoulder breathing, optimizing breathing time ratio by lengthening the expiratory phase (normal inhalation with two times exhalation), and lengthening the pauses between inhalation and exhalation.

To train a well-rounded and calm breathing pattern with slow and deep breathing, it is suitable to prescribe the optimal breathing rhythm. The patient’s unfavorable breathing rhythm is represented by the wave pattern of a swimming fish. Using the principle of pacing, the goal of the exercise is to align one’s own breathing rhythm with the optimal one. The patient should “trace” the optimal pattern as well as possible with the breathing curve.

Primary headache

For primary headaches such as tension headache, atypical facial pain and migraine, biofeedback is considered the most effective non-drug headache treatment [14]. A meta-analysis of 55 studies [15] comprehensively highlighted the effective factors in biofeedback therapies for migraine. Robust medium and stable effects were demonstrated with respect to long-term and durable symptom improvements in severely chronicized pain. Improvements were related to frequency and duration of migraine attacks, pain intensity, medication use, and psychological variables such as depression, anxiety, and self-efficacy. Predictors of success were combination with home-based exercise and female gender and young age. From the treatment recommendations for migraine, the focus is clearly on volume pulse feedback and temperature feedback in extension with relaxation. An important aspect for the success of biofeedback training is the timing of the application of the acquired vascular control. Prophylactically, vasodilation should be used during pain-free periods to manage stress. Vasoconstriction is effective just before or during migraine attacks.

Facial muscles

The targeted training of the facial muscles can be done by means of Progressive Muscle Relaxation according to Jacobson. The principle of systematic contraction and relaxation of different muscles is implemented. Exercise goals are to reduce tension in the forehead and jaw area. By tensing and relaxing the forehead and jaw, predetermined tensile strengths (thresholds: 3, 9, 20 μV) are to be achieved in succession. The point is to closely observe muscle tension and relaxation and pay attention to how tension and relaxation feel different. As a feedback mode, the reward for successfully achieving the specified values is the appearance of a water lily.

In the case of temporomandibular disorders and bruxism, targeted discrimination training of the jaw musculature is suitable: different tension levels are trained at different prefork lines in decreasing tension levels (22, 17, 12, 7 μV). There are practice phases with blind phases with eyes closed. The instruction reads: “In the following, you will first learn to ‘trace’ a given background pattern with your jaw tension”. The line shows your jaw tension. Behind the line of your current muscle tension you will see a given line pattern. You are to find a position that will cause the line to move downward. Activate your muscle tension in such a way that it follows the given line. Pay attention to how this tension feels. Breathe calmly and evenly as you do this.” The instruction “Tense – Release” is recited. In the blind phase, the same pattern is to be reproduced with eyes closed. The previously practiced muscle tension is to be produced in the same rhythm. The previously perceived feeling of the muscles is to be remembered.

Shoulder and neck muscles

To reduce the involvement of the shoulder and neck muscles and expand abdominal breathing, guided breathing and muscle relaxation is recommended. It is explained that permanent incorrect breathing with pronounced involvement of the shoulder and neck muscles in the breathing behavior leads to chronic tension of this area. These tensions become visible in increased EMG values of the trapezius muscle. Line displays (first EMG values of the shoulder muscles, then respiratory behavior, finally both) serve as feedback modes. Instructed is calm and steady abdominal breathing. It is important that the abdominal wall rises and falls during breathing and that the chest and shoulders remain as relaxed as possible.

To reduce the involvement of the shoulder and neck muscles and the expansion of abdominal breathing, the breathing school with EMG control and shoulder relaxation is suitable: instructed to keep the activity of the shoulder muscles below a certain threshold. Exceeding is an indication of pronounced involvement of the shoulder muscles during breathing. Instructed to breathe without the involvement of the shoulders. In the upper half of the screen, a curve is visible that reflects the current abdominal breathing. In the lower half of the screen, the muscle tension of the shoulders is displayed as a line. To achieve is calm abdominal breathing.

As a conclusion of a biofeedback therapy, a relaxation journey with coastal video, relaxation music and simultaneously readable relaxation level with reward when falling below a threshold is recommended.

Conclusion

The differential diagnosis of head/facial pain requires knowledge of a wide range of pathologies from various medical specialties. The complaints from the jaw movement apparatus are characterized by a high prevalence and can be elicited by a careful diagnosis. It is hard to imagine treatment today without the use of biofeedback to control and influence facial pain and headaches. Biofeedback has been shown to increase the effectiveness of common relaxation techniques. As with all procedures, the effectiveness unfolds only after a certain practice time. Patients should always be instructed to practice independently at home on a regular basis using the relaxation instructions provided. In this way, distancing from pain and, as a rule, improved coping with pain are achieved. Consciously incorporating relaxation and regeneration phases into the daily routine is of great benefit for these complaint patterns in order to increase self-efficacy.

Take-Home Messages

- Temporomandibular dysfunctions represent a common clinical picture.

- Extent of structural changes in the temporomandibular joint correlates with pain intensity only to a limited extent.

- Biofeedback is a very good supportive component within pain psychology interventions for headache and facial pain.

- By demonstrably increasing patients’ motivation, biofeedback increases the effectiveness of common relaxation methods (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson).

- Biofeedback has a proven high patient acceptance rate.

Literature:

- Swiss Health Observatory: frequency of back pain or headache 2019; www.obsan.admin.ch/de/indikatoren/ruecken-oder-kopfschmerzen.

- Bigal ME, Bordini CA, Speciali JG: Etiology and distribution of headaches in two Brazilian primary care units. Headache 2000; 40: 241-247.

- Rasmussen BK, Jensen R, Schroll M, Olesen J: Epidemiology of headache in a general population – A prevalence study. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 1991; 44: 1147-1157.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38: 1-211.

- Zakrzewska JM: Multi-dimensionality of chronic pain of the oral cavity and face. J Headache Pain 2013; 14: 37.

- Ettlin D, Gallo L (eds.): The temporomandibular joint in function and dysfunction, Georg Thieme Verlag 2019.

- Bakke M, Petersson A, Wiesel M, et al: Bony deviations revealed by cone beam computed tomography of the temporomandibular joint in subjects without ongoing pain. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014; 28: 331-337.

- Rolke R, Baron R, Maier C, et al: Quantitative sensory testing in the German Research Network on Neuropathic Pain (DFNS): standardized protocol and reference values. Pain 2006; 123: 231-243.

- Manfredini D, Guarda-Nardini L, Winocur E, et al: Research diagnostic criteria for temporomandibular disorders: a systematic review of axis I epidemiologic findings. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2011; 112: 453-462.

- Jensen R, Stovner LJ: Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008; 7: 354-361.

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, et al: Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Group. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014; 28: 6-27.

- Conti PCR, Costa YM, Gonçalves DA, Svensson P: Headaches and myofascial temporomandibular disorders: overlapping entities, separate managements? J Oral Rehabil 2016; 43: 702-715.

- Brenz M: Evaluation of a biofeedback-assisted cognitive-behavioral intervention for chronic tinnitus. Tübingen 2008.

- Rief W, Bernius P: Biofeedback: basics, indications, communication, practical procedure in therapy. Stuttgart, Schattauer 2011.

- Nestoriuc Y, Martin A: Efficacy of biofeedback for migraine: a meta-analysis. Pain 2007; 128: 111-127.

InFo PAIN & GERIATURE 2019; 1(1): 10-15.