Sarcoidosis can occur at any age and typically affects the lungs, but various other organs may also be involved. Diagnosis consists of several steps; there are no specific blood tests to confirm or rule out sarcoidosis. Histologically, sarcoidosis is characterized by epithelioid cell non-necrotizing granulomas. Once pulmonary sarcoidosis has been identified, it is important to look for relevant extrathoracic involvement; cardiac organ manifestations in particular can be life-threatening.

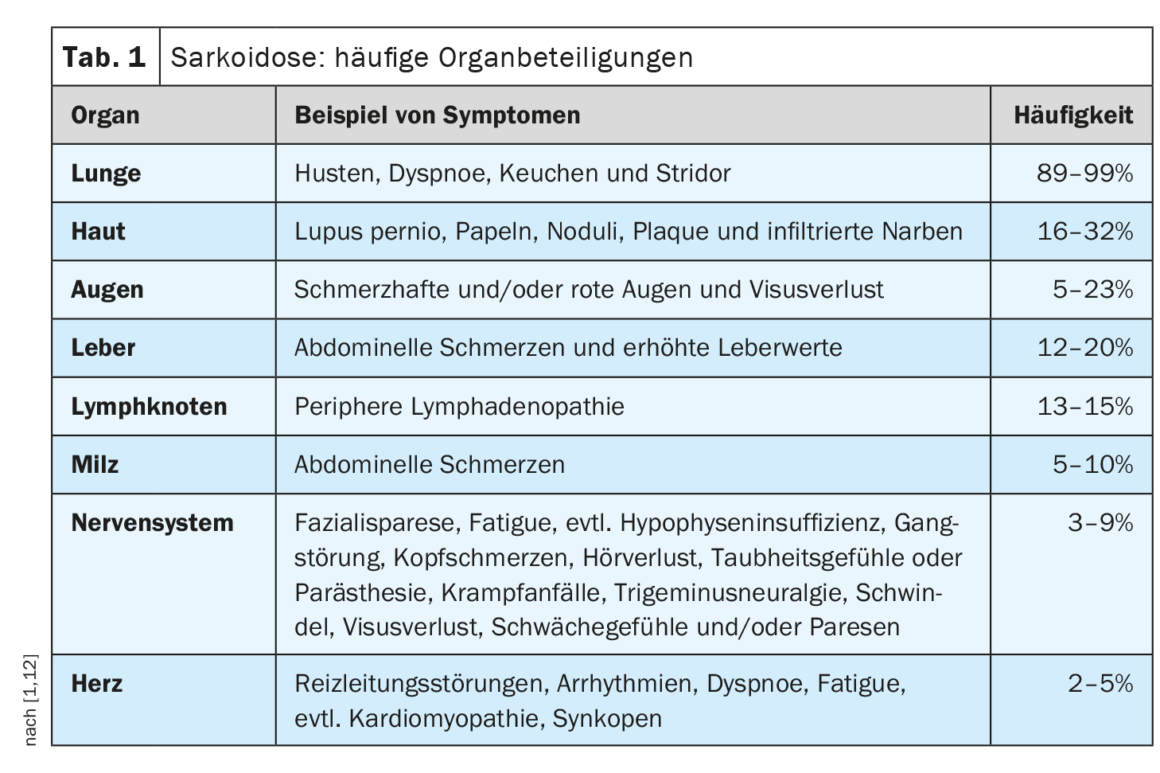

The clinical course and prognosis of sarcoidosis are very heterogeneous and depend on the respective organ involvement, explained Prof. Dr. med. Jörg D. Seebach, médecin chef de Service d’immunologie et allergologie, Hôpitaux universitaires de Genève [1]. The lungs, lymph nodes, skin, and eyes are most commonly affected, while cardiac, renal, and neurological manifestations are less common but are associated with higher morbidity [2]. Table 1 provides an overview of the most common organ manifestations. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based primarily on clinical and radiologic features, identification of non-necrotizing granulomas in one or more tissue samples, and exclusion of other causes of granulomatous disease [1,3]. Sometimes sarcoidosis is self-limiting – about half of sarcoidosis patients experience spontaneous remission within two years and many others within five years of symptom onset [4]. However, there are also severe forms of progression. The most common causes of death in sarcoidosis patients are respiratory failure in advanced pulmonary fibrosis and severe cardiac or neurologic involvement [3]. Table 2 summarizes recommendations for history and screening measures, and Table 3 summarizes clarifications for suspected specific organ involvement.

Bronchoscopic procedures are minimally invasive

If sarcoidosis is suspected based on clinical symptoms and radiographic findings, the speaker recommends ordering a biopsy [1]. In general, histologic specimens should be obtained from the site that offers the least invasive exposure and the best diagnostic capabilities. Since most cases involve the lungs, bronchoscopy is a safe and minimally invasive procedure [2]. There are several diagnostic bronchoscopic procedures, including endobronchial (mucosal) biopsy, transbronchial lung biopsy (TBLB), or transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) of hilar/mediastinal lymph nodes and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). Extrapulmonary biospecimens, e.g., from the skin, parotid or lacrimal glands, palpable lymph nodes, or conjunctival lesions, are also possible but less specific. In any case, histology must be accompanied by compatible clinical and radiological manifestations and exclusion of other diseases. If there is histologic confirmation at extrapulmonary sites and concomitant pulmonary involvement with suspected infection, such as cavitary lung disease, bronchoscopy may be required to exclude infectious causes such as mycobacteria and fungi [2].

Pulmonary manifestation is the most common organ involvement

Involvement of the lungs and/or mediastinal/hilar lymph nodes is the most common organ involvement, occurring in approximately 80-90% of sarcoidosis patients. Pulmonary manifestation is associated with parenchymal involvement and perivascular granulomas. The most common symptoms are a feeling of pressure in the chest, a dry cough and dyspnea. In the later course, fibrosis with respiratory failure may develop [5]. Because pulmonary sarcoidosis can present with obstructive, restrictive, mixed, or normal patterns, pulmonary function test findings are highly nonspecific but important for assessing severity, treatment indication, and treatment response. Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a typical finding in stages 2, 3, and 4 and ranges from subclinical manifestations to end-stage pulmonary fibrosis (stage 4). The latter is irreversible organ damage, whereas sarcoidosis-related mild to moderate ILD is a treatable symptom.

Cardiac manifestation is less common but prognostically unfavorable

While approximately 90% of all sarcoidosis patients have lung involvement, the occurrence of cardiac sarcoidosis is rare, with a prevalence of 2-7% [6]. However, in patients with confirmed extracardiac sarcoidosis, it is recommended to look for cardiac involvement by means of an ECG [7]. This is because cardiac sarcoidosis is a potentially life-threatening manifestation [2]. Modern imaging techniques can be helpful for early detection. These include cardiac MRI with late-gadolinium enhancement (LGE) technique and FDG-PET [8]. Cardiac involvement may be manifested by ventricular arrhythmias, high-grade heart block, or chronic heart failure due to myocardial granulomatous infiltration and/or fibrosis in later stages of the disease [2]. Possible symptoms include chest pain, palpitations, dizziness, and syncope. Sudden cardiac death occurs in up to 25%. In summary, early diagnosis and treatment of cardiac involvement is essential [2,9]. Typical manifestations of cardiac sarcoidosis include conduction disorders, ventricular arrhythmias, and heart failure [13]. In about a quarter of cases, cardiac sarcoidosis occurs in isolation and without pulmonary involvement, according to Prof. Seebach [1]. This is often associated with a worse prognosis compared to systemic sarcoidosis with cardiac involvement. Important differential diagnoses include: lymphocytic myocarditis, some genetic cardiomyopathies, physiological increased FDG uptake in heart failure [1].

Differential diagnostics: what to consider?

“Differential diagnosis is very important,” the speaker emphasized [1]. Histopathological findings are of great importance in this context. Sarcoidosis is characterized by compact, non-necrotizing granulomas with a perilymphatic distribution along the bronchovascular bundles, paraseptally and pleurally [2]. In open lung biopsies, sarcoidosis is often associated with granulomatous vasculitis without destruction of the vessel walls. Hyalinized fibrosis with remnants of granulomas dominates during disease progression. Chronic berylliosis is an essential differential diagnosis to sarcoidosis, especially in patients with exposure to metals. Also to be considered is infliximab-induced granulomatous disease. These entities can be readily distinguished histologically from sarcoidosis. Other differential diagnoses include malignancies (lymphomas, carcinomas), vascular collagenoses (systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, primary biliary cirrhosis, familial granulomatous arthritis), infections (HIV, tuberculosis), vasculitis (granulomatosis with polyangiitis, Takayasu arteritis, giant cell arteritis), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, pneumoconiosis/dust lung, IgG4-related disease, and various immunodeficiency diseases) [2,10,11]. The morphology and distribution pattern of the related granulomas differ from sarcoidosis.

Infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, Myobacterium avium, histoplasmosis, coccidiomycosis, and Whipple’s disease) show peribroncheal or random distribution of granulomas and are often associated with necrosis. The use of special stains (Ziehl-Neelsen, auramine, and silver stains) or PCR assays for Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex and atypical myobacteria can be informative for pathogen detection. In contrast to sarcoidosis, hypersensitivity pneumonitis is characterized by loose accumulations of histiocytes near the bronchioles. Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (formerly also called Wegener’s granulomatosis) is characterized by basophilic necrosis surrounded by a cellular infiltrate containing giant cells. Nodular sarcoid granulomatosis is sometimes considered a variant of sarcoidosis and is also characterized by extensive necrosis, which, unlike granulomatosis with polyangiitis, is eosinophilic and demarcated by numerous compact granulomas accompanied by granulomatous vasculitis without destruction of the vessel walls.

Differential diagnoses in case of neurologic manifestations should be based on MRI findings (especially periventricular focal lesions vs. parenchymal lesions or meningeal lesions). New MRI techniques have optimized sensitivity, but due to lack of specificity, diagnostic containment remains a challenge. [2]. Differential diagnoses range from autoimmunologic, inflammatory, or idiopathic diseases (e.g., MS, neuromyelitis optica spectrum disease, SLE, Sjögren’s syndrome, Behcet’s disease, primary CNS vasculitis) to infectious entities (e.g., tuberculosis, Lyme disease, neurosyphilis, taxoplasmosis) and neoplasms (primary CNS neoplasms, lymphomas, and others) [2].

Literature:

- «Sarcoidosis: Beyond the Lungs and Lymph Nodes», Prof. Dr. med. Jörg D. Seebach, Allergy and Immunology Update, Grindelwald, 27.–29.1.2023.

- Franzen DP, et al.: Sarcoidosis – a multisystem disease. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;152: w 30049.

- Graf L, Geiser T: Das Chamäleon unter den Systemerkrankungen: «Die Sarkoidose». Swiss Med Forum 2018; 18(35): 695–701.

- Valeyre D, et al.: Sarcoidosis. Lancet (London, England) 2014; 383(9923): 1155–1167.

- Lichtenberger N: Diagnostik und Therapie der Kardialen und pulmonalen Sarkoidose. https://opus.bibliothek.uni-wuerzburg.de, (last accessed 23.02.2023)

- Costabel U, et al. [Cardiac sarcoidosis: diagnostic and therapeutic algorithms]. Pneumologie (Stuttgart, Germany) 2014; 68(2): 124–132.

- Birnie DH, et al.: HRS expert consensus statement on the diagnosis and management of arrhythmias associated with cardiac sarcoidosis. Heart rhythm 2014; 11(7): 1305–1323.

- Giblin GT, et al.: Cardiac Sarcoidosis: When and How to Treat Inflammation. Card Fail Rev 2021;7:e17. doi: 10.15420/cfr.2021.16.

- Hamzeh N, et al.: Pathophysiology and clinical management of cardiac sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Cardiol 2015; 12(5): 278–288.

- Valeyre D, et al.: Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis and diagnostic work-up. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2014; 35(3): 336–351.

- Spagnolo P, et al.: Pulmonary sarcoidosis. Lancet Respir Med 2018; 6(5): 389–402.

- Grunewald J, et al.: Sarcoidosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2019; 5(1): 45.

- Birnie D, et al.: Cardiac Sarcoidosis. Clinics in chest medicine 2015; 36(4): 657–668.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2023; 18(5): 40–42

Cover photo: Hellerhoff, wikimedia