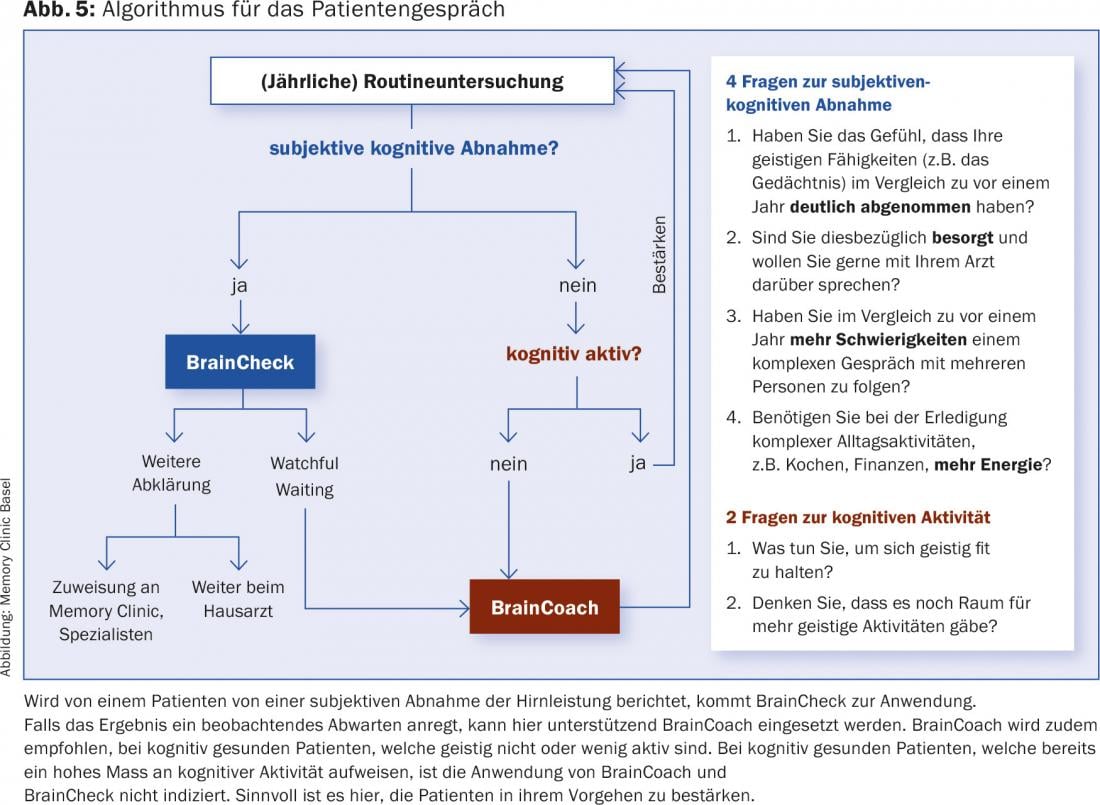

Early detection of brain disorders allows causal treatment of the underlying pathology in about 10% of cases and, in the case of irreversible neurodegenerative diseases, delay of deterioration by initiating appropriate pharmacological and non-pharmacological interventions. BrainCheck provides primary care physicians with a very efficient and easy-to-use case-finding tool, the results of which allow them to decide whether further clarification is necessary or whether it is possible to wait (watchful waiting). Cognitive reserve represents a potential protective factor against dementing developments and should allow for prolonged compensation through increased brain connectivity. Improvement in cognitive reserve can also be sought at a later stage of life through regular mental activity. By asking simple questions, the patient interview algorithm can be used to quickly decide if and when the use of BrainCheck, BrainCoach, or a combination of both tools is indicated.

Demographic developments, with the steadily growing number of older people, are leading to an increase in the prevalence of age-associated diseases, such as dementia. According to estimates [1], almost 200,000 people will be living with dementia in Switzerland as early as 2030, representing a major economic, medical and social challenge. Health in old age is therefore gaining in importance and it is necessary to introduce appropriate early detection and prevention measures with regard to the issue of “cognitive decline”. The importance of identifying brain disorders as early as possible is substantiated by the fact that about 10% of the underlying causes are treatable and thus at least partially reversible [2]. Moreover, in the case of neurodegenerative diseases, early initiation of pharmacological and non-pharmacological therapy may prolong the maintenance of quality of life [3].

BrainCheck: High sensitivity and specificity

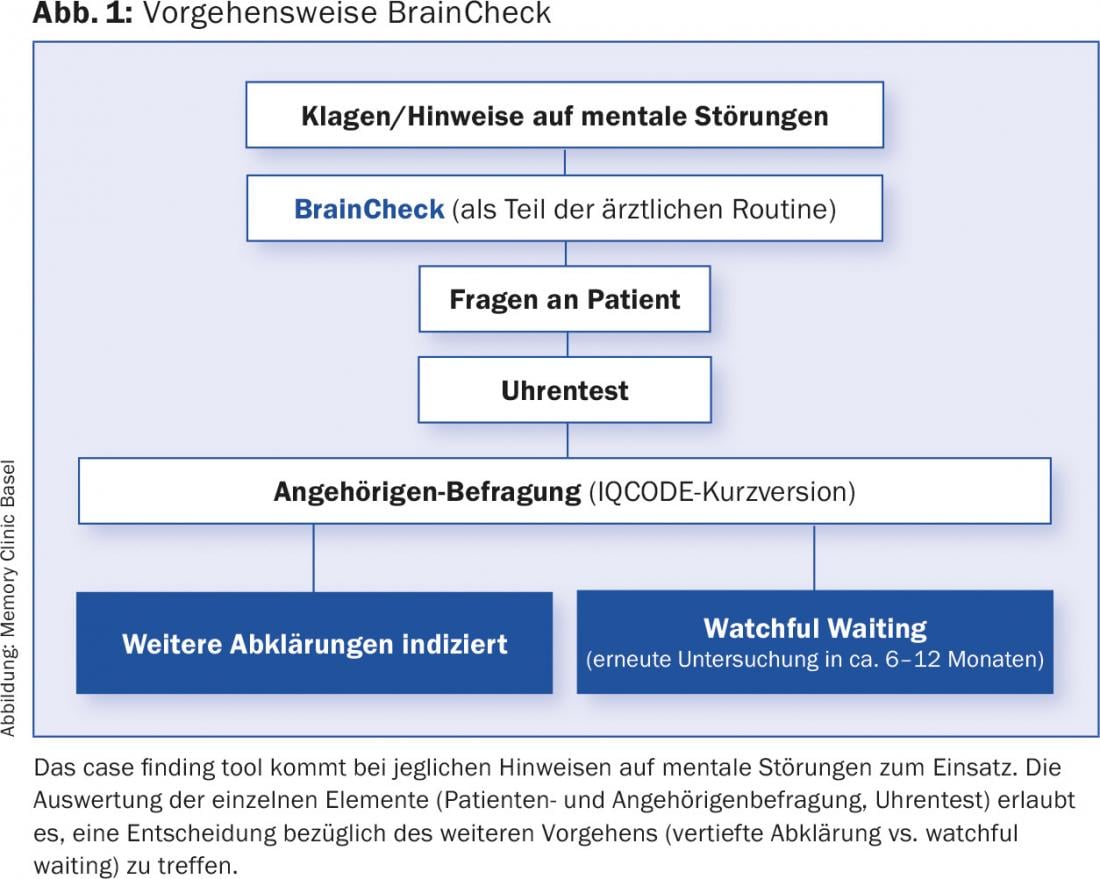

To facilitate the early detection of cognitive symptoms in elderly persons, the case-finding tool “BrainCheck “* was developed under the leadership of the Memory Clinic Basel and in collaboration with 5 other memory clinics in Switzerland [4]. This can be used in the family practice setting when. (a) from the patient or (b) a relative is reported to have changes in brain performance; or if (c) suspicions arise in this regard from the family physician himself. With the help of three questions for the patient and the clock test as well as a very short questionnaire for the relatives – which they can easily fill out in the waiting room – a decision can be made in about 3 minutes with almost 90 percent reliability as to whether further clarification of the brain performance (by the family doctor or in a memory clinic) or “watchful waiting” is indicated. (Fig. 1).

BrainCheck as a case-finding tool is very fast and easy to perform and has a high sensitivity and specificity. In addition, the instrument is available free of charge in German, English, French, Italian and Spanish at www.memoryclinic.ch and at www.braincheck.ch. Furthermore, an app is available for the iPhone and iPad.

Potentially influenceable risk factors

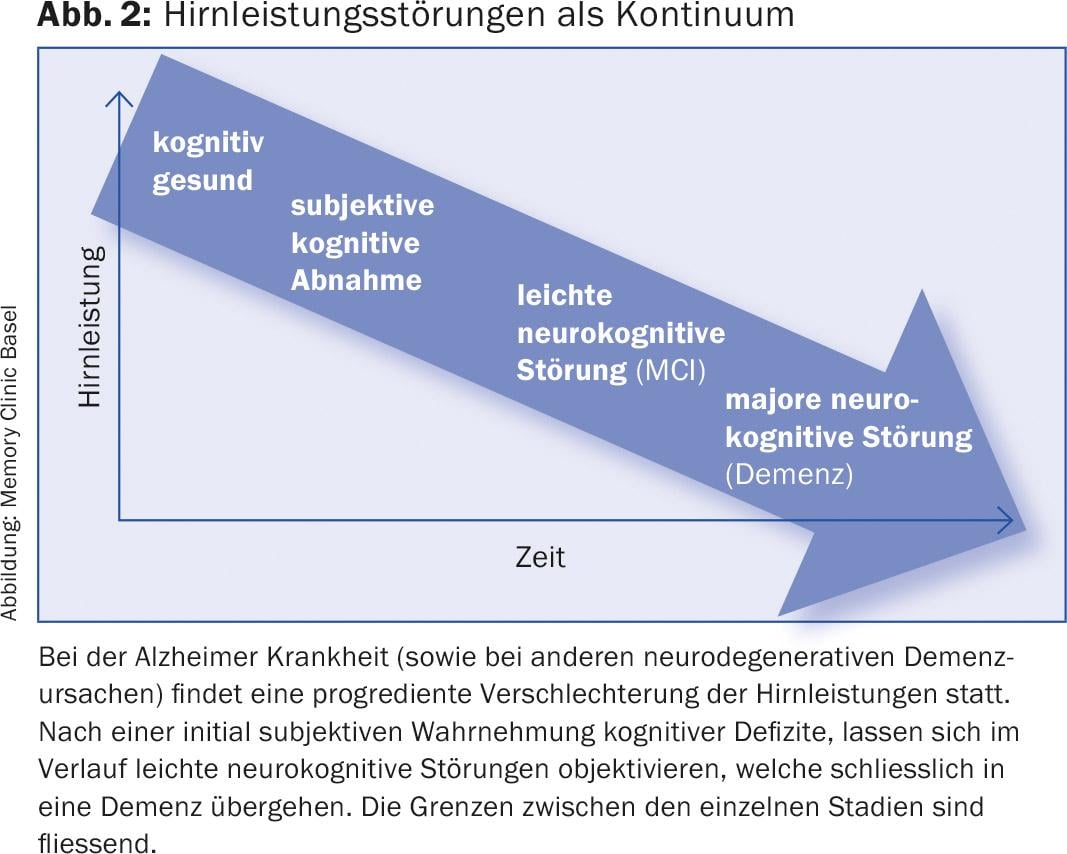

In addition to the early detection of brain disorders, another focus of current research is on the prevention of cognitive decline or brain damage. on the delay of deterioration in the case of already existing only subjective or very slight objectifiable cognitive disorders. Alzheimer’s disease, the most common and therefore most important cause of dementia, is used as a model in these considerations. In Alzheimer’s disease, there is a continuous deterioration from initially normal performance to only subjective, then mild cognitive impairment to dementia (Fig. 2) . In recent years, in addition to non-modifiable risk factors such as age or genetic predisposition, risk factors that can potentially be influenced have also been discussed [5].

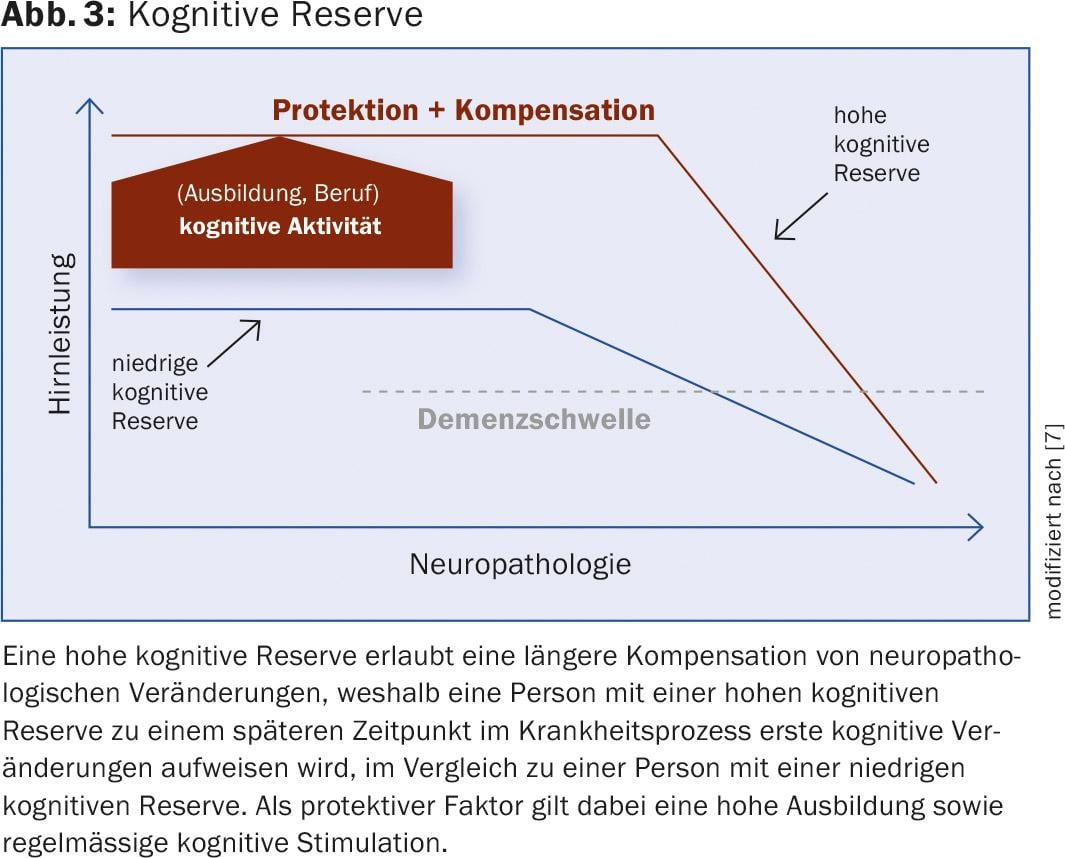

An important protective factor against cognitive decline is, among others, mental activity, which is also discussed under the concept of “cognitive reserve” [6]. Studies have shown that individuals with a high level of education or regular cognitive stimulation are better able to compensate for neuropathological processes for longer periods of time in the event of the onset of dementia by increasing brain connectivity (Fig. 3) [7]. The type of mental activity is not decisive – what is important is that something is done that gives pleasure. And the principle is: “The more, the better”.

BrainCoach: Use it or lose it!

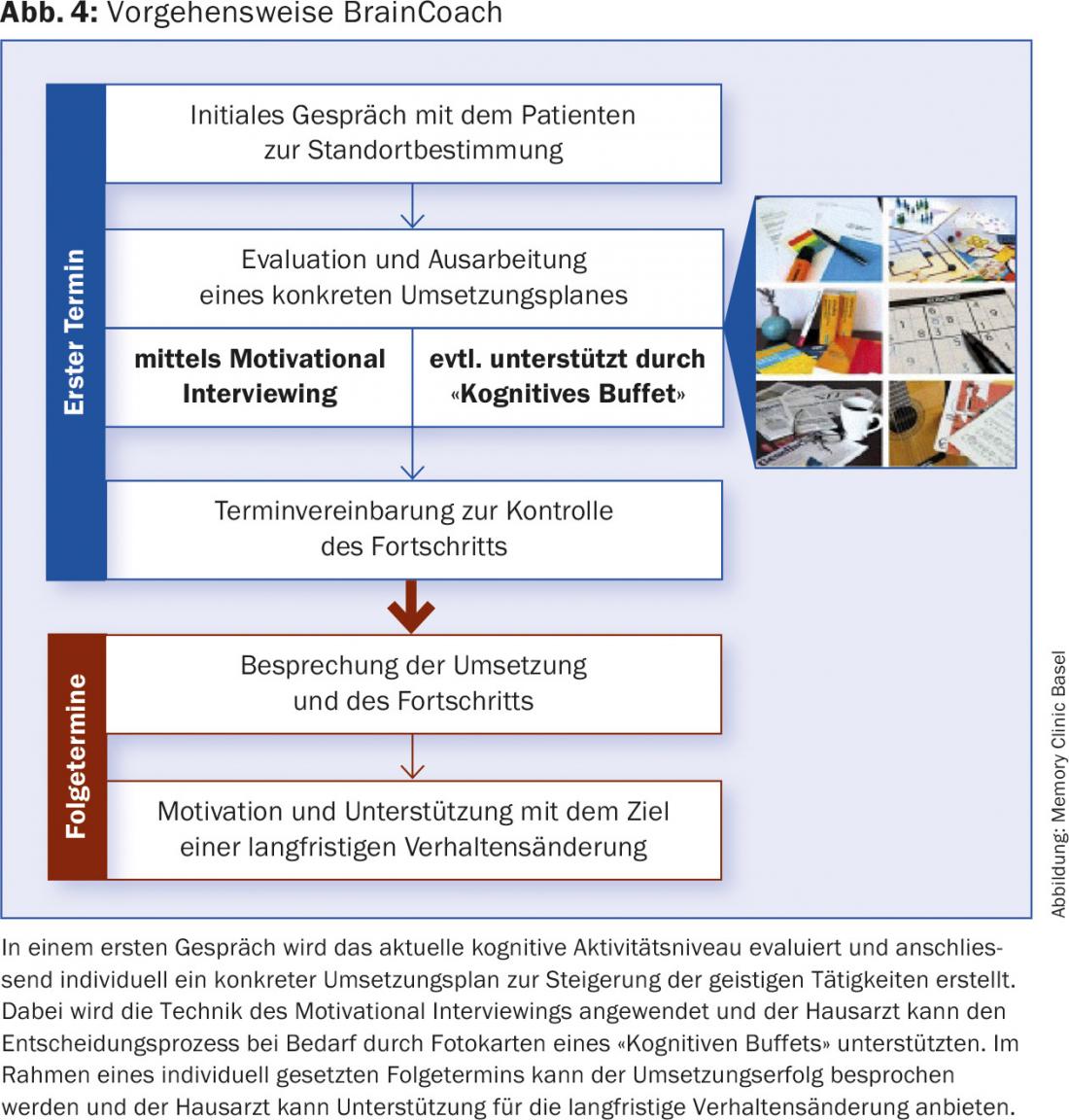

In order to support older, less active or, for example, “cognitively bored” persons as a result of retirement, to increase their mental agility and thus also their cognitive reserve, the program “BrainCoach* – Use it or lose it” was developed with the help of a Swiss group of experts at the Memory Clinic Basel, which is to be implemented primarily in family practices [8]. Using the technique of “Motivational Interviewing”, the aim is to increase the intrinsic motivation of older people to engage in cognitive activity. The program is aimed at healthy elders as well as people with subjective (i.e., [noch] not objectifiable) cognitive decline – but never at patients with dementia.

In a first step, the subjective importance of increasing one’s own mental activity is to be determined in the course of an interview. The patient is then asked to think of activities that he or she currently enjoys doing or that he or she has done in the past. If necessary, the general practitioner can facilitate this finding process by presenting photo cards of a “cognitive buffet” (Fig. 4). After a concrete turnover plan has been worked out in detail, a follow-up appointment is made to evaluate progress, based on the patient’s individual needs (Fig. 4).

Currently, the BrainCoach program is being tested in a pilot/feasibility study in Basel and in Geneva in collaboration with primary care physicians and their medical practice assistants. The results from Basel of 5 family physicians who together counseled 12 patients (5 women, 7 men; age [Median] = 70) with BrainCoach showed that by means of the prepared documents and the suggested technique an increase in the patients’ motivation for mental activity could be achieved. If the results of the pilot study in Geneva are equally positive, there is nothing standing in the way of dissemination.

Algorithm for the patient interview

For which patients BrainCheck, BrainCoach or both modules are applicable can be evaluated using an algorithm for the patient interview (Fig.5). The sample questions on cognitive activity and subjective cognitive decline (SCD, [9]) can be evaluated in a casual conversation, for example, during blood sampling by the medical practice assistant. She can then forward the result and the indicated further steps (affirmation regarding cognitive activity; BrainCheck; BrainCoach) to the attending general practitioner.

* Both projects were and are being conducted under the direction of the Memory Clinic Basel and with the grateful support of an unrestricted grant from Viforpharma.

Literature:

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2016. Improving healthcare for people living with dementia. Alzheimer’s Disease International (ADI), London. September 2016 (www.alz.co.uk/research/world-report-2016).

- Clarfield AM: The decreasing prevalence of reversible dementias: an updated meta-analysis. Arch Intern Med 2003;163(18): 2219-29.

- Monsch AU, et al: Swiss Expert Group. Consensus 2012 on diagnosis and treatment of dementia patients in Switzerland. Praxis 2012;101(19):1239-49.

- Ehrensperger MM, et al: BrainCheck – a very brief tool to detect incipient cognitive decline: optimized case-finding combining patient- and informant-based data. Alzheimers Res Ther 2014;6(9):69. doi: 10.1186/s13195-014-0069-y.

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. World Alzheimer Report 2014. Dementia and risk reduction – An analysis of protective and modifiable factors. London: Alzheimer’s Disease International; October 2014 (www.alz.co.uk/research/WorldAlzheimerReport2014.pdf).

- Stern Y: Cognitive reserve in aging and Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet Neurol 2012;11(11):1006-12. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70191-6.

- Stern Y: Cognitive reserve. Neuropsychologia 2009;47(10): 2015-28. doi: 10.1016/j. neuropsychologia. 2009.03.004

- Mistridis P, et al: Use it or lose it! Cognitive activity as a protective factor for cognitive decline and dementia in older adults. Swiss Medical Weekly. (in press).

- Molinuevo JL, et al: Subjective Cognitive Decline Initiative (SCD-I) Working Group. Implementation of subjective cognitive decline criteria in research studies. Alzheimers Dement 2016 Nov 5. pii: S1552-5260(16)33019-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2016.09.012. [Epub ahead of print].

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2017; 12(2): 8-12