In the case of frequent headaches, prophylactic medication may be useful. What medications are available and what is the evidence for their efficacy?

About 15% of the European population suffers from migraine attacks [1]. In the process, affected individuals are not only confronted with pain, but also have to cope with the effects of the disease on their professional and private lives [2]. However, the burden of the disease is not the same for everyone, but increases with the number of headache days.

Although numerous, often well effective medications are available for the acute treatment of migraine, this therapeutic approach is not always sufficient. Running after the pain, as it were, instead of preventing it, reduces the duration of attacks but does not necessarily increase the predictability of life. In addition, frequent use of acute medications carries the risk of medication overuse headache (MÜKS) [3]. This is imminent if simple analgesics are taken on ≥15 days or triptans, opiates, or combined analgesics are taken on more than ten days per month over a prolonged period (at least three months). It is much more costly to society than migraine itself, and comes with additional burdens for the individual [4,5].

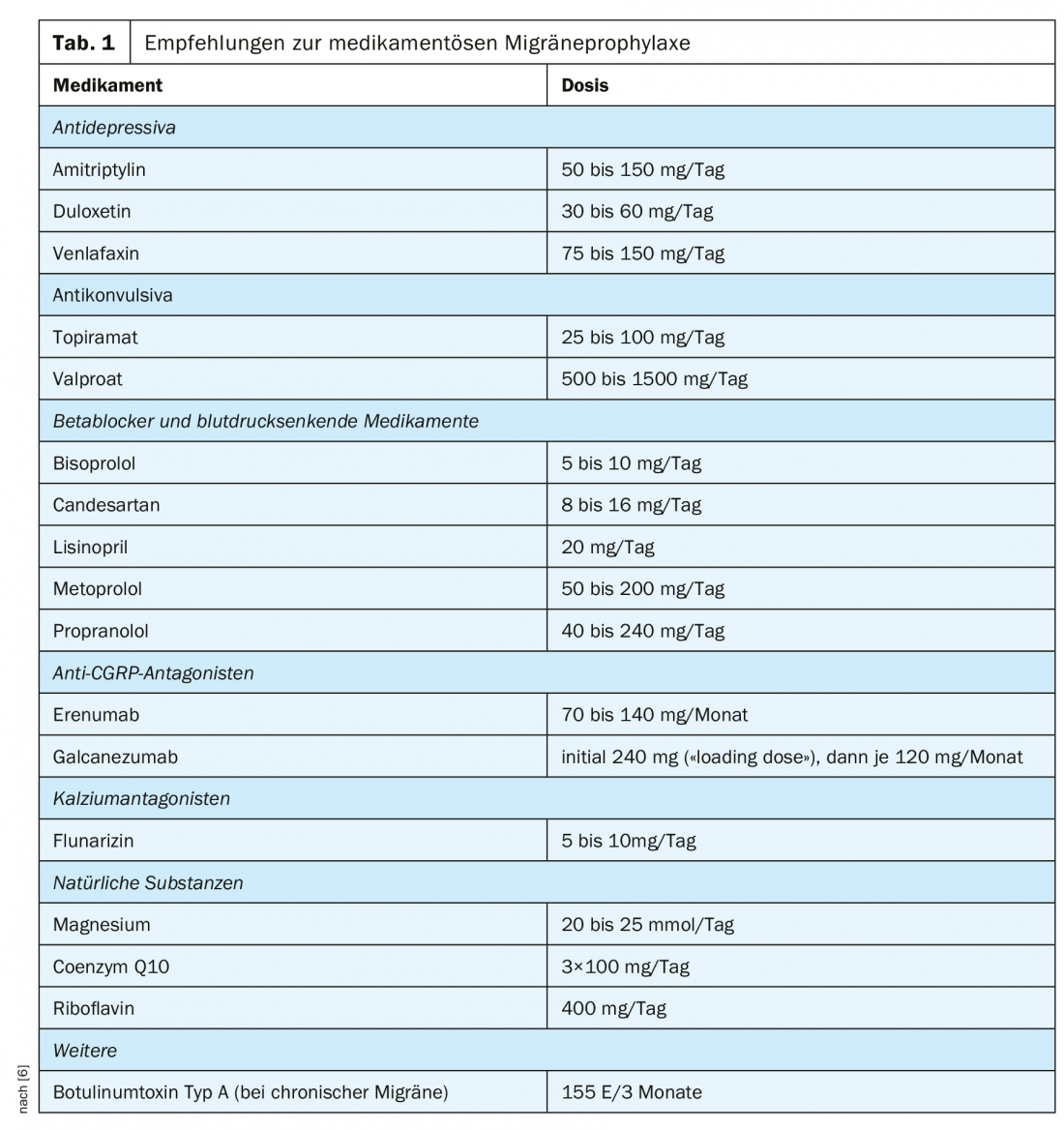

So the goal is to prevent the seizures from occurring in the first place, or at least to reduce their number as much as possible. Various agents have been shown to be helpful in this regard (Tab. 1) [6]. However, choosing the right time for prophylaxis and selecting the right medication can be challenging. On the other hand, this treatment approach offers the chance to significantly alleviate the symptoms of those affected.

Therapy principles

Basically, a distinction is made between drug and non-drug therapeutic approaches. It is usually assumed that starting prophylactic treatment is reasonable at five or more headache days or at least three migraine attacks per month [6]. An individual therapy decision is advisable, as not all sufferers are restricted by their headaches to the same extent. If the burden of single attacks is already very high (e.g., in hemiplegic migraine or long-lasting attacks), prophylaxis can be considered even if the number of headache days is low.

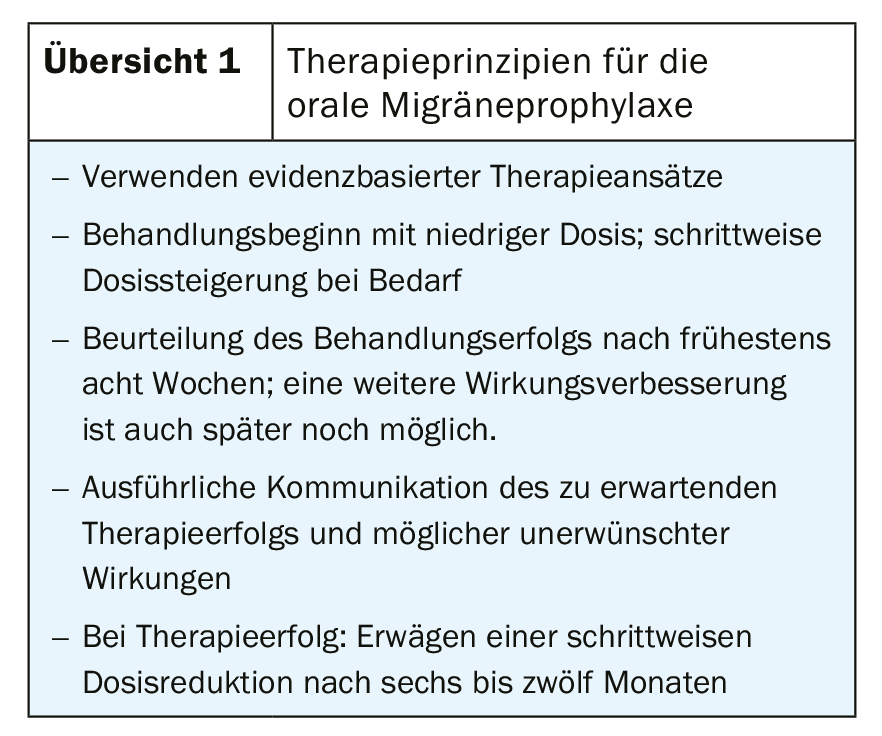

Before starting therapy, patients should be informed in detail about the opportunities and risks of the treatment. Successful therapy often takes several weeks, while side effects often become noticeable much sooner.

Non-drug methods such as neuromodulation, non-invasive vagus nerve stimulation, relaxation techniques, biofeedback, and transcranial magnetic stimulation are often effective but not always sufficient. In this article, we will limit our discussion to the options for migraine prophylaxis with medication.

Oral medications for migraine prophylaxis must be used daily – regardless of whether pain is currently present. Evaluation of treatment success is difficult because the number of headache days is retrospectively underestimated [7]. Therefore, patients on seizure prophylaxis should be sure to keep a headache calendar (3-6 months). Therapy adherence, which is often very low, should also be encouraged and inquired about [8].

Nevertheless, in order to achieve therapeutic success, we consider detailed counseling, individual selection of medications, and an assessment of changes that have occurred that is as objective as possible to be essential (overview 1).

Medication

In general, we recommend starting with a low dose and increasing it slowly as needed. If treatment is successful, a gradual dose reduction can be considered after six to twelve months.

Beta-blockers and other antihypertensive drugs: That beta-blockers are helpful in migraine prophylaxis was discovered by chance [9]. They reduce the amplitudes of visual evoked potentials that are often elevated in migraine patients, which may indicate an improvement in the function of thalamo-cortical connections [9–13]. However, whether this is responsible for the reduction in migraine frequency has not yet been conclusively determined [9,12].

The efficacy of propranolol [14] and metoprolol [15,16], both of which are approved in Switzerland for migraine prophylaxis [17], has been confirmed in several studies.

Candesartan is similarly effective to propranolol and the side effects of the two drugs are also similar. While dizziness and paresthesias have been reported more frequently with candesartan, episodes of bradycardia are more common with propranolol [18].

Lisinopril was studied in two smaller trials and also showed a prophylactic effect; however, individual patients had to discontinue treatment because of cough [19,20].

Calcium antagonists: the calcium antagonist flunarizine is also approved for migraine prophylaxis [17]. Its efficacy can be considered assured, although some studies showed underpowered [21]. The mechanism of action is not known, but blockade of cortical voltage-gated sodium and calcium channels has been discussed [22]. The most common side effects are fatigue and weight gain, while depressed affect or extrapyramidal syndrome are very rarely reported [21].

Antidepressants: In Switzerland, no antidepressant is currently approved for the prophylaxis of migraine, but their use is nevertheless supported by current treatment recommendations [6]. However, in our experience, many patients have clear reservations about these drugs.

The best studied is amitriptyline, which reduces the number of migraine days more than a placebo [23]. Tricyclics enhance the anti-nociceptive effect of descending pathways and reduce spreading depression in animal studies, which may explain their effect in migraine prophylaxis [24–26].

The evidence for the efficacy of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors is considerably worse [24]. Fluoxetine showed little [27] or no effect in trials [28]; sertraline had no effect on headache severity [29]. In contrast, the SNRI venlafaxine significantly reduced the number of headache days in a placebo-controlled trial [30]. To our knowledge, the effect of duloxetine-also an SNRI-has not yet been tested in any randomized controlled trial. However, evidence of good efficacy in some patients emerged from a retrospective [31] and a prospective open-label study [32].

Anticonvulsants: From the group of anticonvulsants, only topiramate is currently approved for migraine prophylaxis in Switzerland [17]. Numerous studies have confirmed the good efficacy of the drug [33–37]. However, side effects such as fatigue, paresthesias, nausea, and impaired concentration limit its usefulness [35,38].

The effect of valproate is also well documented [39–41]. However, it must be noted with both drugs that the risk of malformation is significantly increased when used during pregnancy and therefore effective contraception is necessary in women of childbearing age [42].

In general, anticonvulsants are thought to prevent scatter polarization as well as central sensitization, thereby reducing the frequency of migraine attacks [43]. However, other anticonvulsants such as acetazolamide, clonazepam, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, vigabatrin, and gabapentin have not been shown to be effective [44,45].

Anti-CGRP antibodies: After the first description of the “calcitonin gene-related peptide” (CGRP) in 1983 [46], its vasodilating effect [47] and significance for headache disorders were recognized in the following years [48]. The first antagonists were soon developed and tested [49–51]. Finally, monoclonal antibodies directed either against the CGRP molecule itself or its receptor reached market maturity [52–58]; all significantly reduce the number of headache days.

Currently available in Switzerland are erenumab and galcanezumab, which can be injected subcutaneously at home [59,60]. So far, the drugs appear to be well tolerated; the frequency and type of adverse events differed at most only slightly from the placebo group-only pain and itching at the injection site occurred more frequently in the verum group in one study [52, 54, 56, 58]. However, long-term data on tolerability and effects as well as information on possible embryotoxicity are not yet available.

Magnesium: Migraine attacks are thought to be related to low serum magnesium concentration [61,62]. The reason for this could be that magnesium normally inhibits NMDA receptors [63,64] as well as decreases nitric oxide production [65,66] and this effect is reduced in hypomagnesemia.

In individual – but not all [67,68] – studies, magnesium supplementation shortened seizure duration [69] or reduced frequency [70]. However, a meta-analysis did not confirm the benefit in acute treatment [71]. With individualized dosing and timing, treatment is usually well tolerated [67]. However, caution is advised when using it during pregnancy.

Riboflavin: The effect of riboflavin on migraine has been investigated in several studies. This was based on the consideration that mitochondrial dysfunction may play a role in the pathophysiology of migraine [72] and riboflavin in high doses increases the activity of complexes I and II of the respiratory chain in certain diseases [73,74].

It was shown that in adults, high doses (400 mg/day) can lead to a reduction in seizure frequency [74,75], whereas this effect could not be reproduced in children [76]. Diarrhea and polyuria are reported as the most common side effects [74].

Coenzyme Q10: Also behind the use of coenzyme Q10 is the thought that mitochondrial dysfunction may be a cause of migraine [77]. It accepts electrons generated in complexes I and II of the respiratory chain and transports them further to complex III [78].

In adults, the treatment showed significant efficacy in migraine prophylaxis in a randomized controlled trial [77] and two open-label studies [79,80]. This effect was not reproduced in children [81]. No side effects have been reported.

Pregnancy

During pregnancy, the number of migraine days temporarily decreases in a large proportion of patients [82,83], while migraine attacks are common immediately after delivery [84]. Often, no drug prophylaxis is needed during pregnancy. Instead, non-drug methods (acupuncture, neuromodulation, biofeedback and sleep hygiene, etc.) are recommended [85,86]. If abstaining from medication is not an option, the use of propranolol and metoprolol as well as amitriptyline may be considered [85]. However, the two beta-blockers have been associated with decreased birth weight and amitriptyline with infant adjustment disorders [42]. Although these drugs have not been evaluated as teratogenic, careful risk-benefit consideration is still necessary.

Recommendations for magnesium supplementation during pregnancy should be viewed with more caution [85]. It has since become known that the use of magnesium sulfate can lead to osteopenia in infants [87], which is why the FDA advises against its use for tocolysis for periods longer than five to seven days [88].

Since it is not known at what dose osteopenia occurs and the risk can therefore not be quantified, the use of magnesium for migraine prophylaxis during pregnancy has now also been discouraged [89].

Menstrual migraine

About 50% of women with migraine describe an increase in the frequency of attacks during menstruation; however, exclusive occurrence during menstruation is rare [82]. Especially in women with frequent attacks, it must be considered that these can also occur coincidentally perimenstrually [90]; an exact delimitation is often only possible with a migraine diary that has been kept over a longer period of time [91]. Menstruation-associated attacks often last longer and are more likely to be associated with nausea [92].

It is recommended that women with migraine attacks that do not always occur in temporal relation to menstruation take “normal” prophylaxis, as discussed above [90]. However, if the seizures are closely associated with the period and the affected person has a regular cycle, this can be useful in treatment planning because the occurrence of the symptoms is predictable. In these cases, NSAIDs and triptans (subject to contraindications and warnings) can be taken as “short-course prophylaxis” for four to seven days [90]. In addition, whereas estrogen gel was previously recommended for short-term prophylaxis [93] and estrogen-containing contraception was recommended to prolong cycles [94], guidelines have since changed with regard to cardiovascular risk [6,95]. Currently, progestogen-containing contraceptives are recommended [6]. In any case, treatment of menstrual migraine should be done in consultation with a gynecologist.

Chronic migraine

Chronic migraine is present when a patient has headaches ≥15 days per month for at least three months, with at least eight days meeting criteria for a migraine attack [3]. Its prevalence ranges from 1.4 to 2.2% in the general population [96]. A large proportion of those affected also have a FMD [97], for which other treatment recommendations apply (see below).

Placebo-controlled studies have confirmed that topiramate [38,98,99], botulinum toxin [100–103], valproate [104] and erenumab [54], galcanezumab [58] and fremanezumab (not yet commercially available in Switzerland). [57] can significantly reduce the number of headache days. We therefore recommend that these medications be preferred in the treatment of chronic migraine.

Medication Overuse Headache

Medication overuse headache (MÜKS) is common-an estimated prevalence of 1 to 2% [105] -and must always be suspected in patients with many headache days. Treatment consists of not taking acute medication [106]. That additional drug prophylaxis is helpful is doubted [106], but definitive statements are not yet possible. Before starting the medication break, it is of great importance to inform the patient well about the duration and expected benefits. Initially (for about four weeks), there may be a temporary increase in the frequency of headaches, and even later, freedom from pain is not to be expected. The goal of treatment is a decrease in attack frequency to pre-drug overuse levels.

Take-Home Messages

- If the number of headache days increases or the need for acute medications becomes more frequent, prophylaxis should be discussed.

- When selecting a drug, its side effects as well as the patient’s living conditions and acceptance of the therapy must always be taken into account.

- Migraine prophylaxis offers the opportunity to significantly reduce the stress patients experience in their daily lives.

Literature:

- Stovner LJ, Andree C: Prevalence of headache in Europe: a review for the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 2010; 11(4): 289-299.

- Lampl C, et al: Interictal burden attributable to episodic headache: findings from the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 2016; 17: 9.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS): The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia 2018; 38(1): 1-211.

- Linde M, et al: The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol 2012; 19(5): 703-711.

- Westergaard ML, et al: Prevalence of chronic headache with and without medication overuse: associations with socioeconomic position and physical and mental health status. Pain 2014; 155(10): 2005-2013.

- Andrée C, et al: Treatment recommendations for primary headache. Swiss Headache Society SKG, 2019.

- Krogh AB, et al: A comparison between prospective Internet-based and paper diary recordings of headache among adolescents in the general population. Cephalalgia 2016; 36(4): 335-345.

- Hepp Z, Bloudek LM, Varon SF: Systematic review of migraine prophylaxis adherence and persistence. J Manag Care Pharm 2014; 20(1): 22-33.

- Danesh A, Gottschalk PCH: Beta-Blockers for Migraine Prevention: a Review Article. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2019; 21(4): 20.

- Schoenen J, et al: Evoked potentials and transcranial magnetic stimulation in migraine: published data and viewpoint on their pathophysiologic significance. Clin Neurophysiol 2003; 114(6): 955-972.

- Brinciotti M, et al: Responsiveness of the visual system in childhood migraine studied by means of VEPs. Cephalalgia 1986; 6(3): 183-185.

- Gerwig M, et al: Beta-blocker migraine prophylaxis affects the excitability of the visual cortex as revealed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. J Headache Pain 2012; 13(1): 83-89.

- Nyrke T, et al: Steady-state visual evoked potentials during migraine prophylaxis by propranolol and femoxetine. Acta Neurol Scand 1984; 69(1): 9-14.

- Linde K, Rossnagel K: Propranolol for migraine prophylaxis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004(2): CD003225.

- Hedman C, et al: Symptoms of classic migraine attacks: modifications brought about by metoprolol. Cephalalgia 1988; 8(4): 279-284.

- Langohr HD, et al: Clomipramine and metoprolol in migraine prophylaxis – a double-blind crossover study. Headache 1985; 25(2): 107-113.

- Swiss Agency for Therapeutic Products Swissmedic. Drug Information. Last accessed on 07/31/2019.

- Stovner LJ, et al: A comparative study of candesartan versus propranolol for migraine prophylaxis: A randomised, triple-blind, placebo-controlled, double cross-over study. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(7): 523-532.

- Schrader H, et al: Prophylactic treatment of migraine with angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (lisinopril): randomised, placebo controlled, crossover study. BMJ 2001; 322(7277): 19-22.

- Schuh-Hofer S, et al: Efficacy of lisinopril in migraine prophylaxis – an open label study. Eur J Neurol 2007; 14(6): 701-703.

- Stubberud A, et al: Flunarizine as prophylaxis for episodic migraine: a systematic review with meta-analysis. Pain 2019; 160(4): 762-772.

- Ye Q, et al: Flunarizine blocks voltage-gated Na(+) and Ca(2+) currents in cultured rat cortical neurons: A possible locus of action in the prevention of migraine. Neurosci Lett 2011; 487(3): 394-399.

- Xu XM, et al: Tricyclic antidepressants for preventing migraine in adults. Medicine 2017; 96(22): e6989.

- Burch R: Antidepressants for Preventive Treatment of Migraine. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2019; 21(4): 18.

- Ayata C, et al: Suppression of cortical spreading depression in migraine prophylaxis. Ann Neurol 2006; 59(4): 652-661.

- Sprenger T, Viana M, Tassorelli C: Current Prophylactic Medications for Migraine and Their Potential Mechanisms of Action. Neurotherapeutics 2018; 15(2): 313-323.

- Steiner TJ, et al: S-fluoxetine in the prophylaxis of migraine: a phase II double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 1998; 18(5): 283-286.

- Saper JR, et al: Double-blind trial of fluoxetine: chronic daily headache and migraine. Headache 1994; 34(9): 497-502.

- Landy S, et al: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for migraine prophylaxis. Headache 1999; 39(1): 28-32.

- Ozyalcin SN, et al: The efficacy and safety of venlafaxine in the prophylaxis of migraine. Headache 2005; 45(2): 144-152.

- Taylor AP, Adelman JU, Freeman MC: Efficacy of duloxetine as a migraine preventive medication: possible predictors of response in a retrospective chart review. Headache 2007; 47(8): 1200-1203.

- Young WB, et al: Duloxetine prophylaxis for episodic migraine in persons without depression: a prospective study. Headache 2013; 53(9): 1430-1437.

- Brandes JL, et al: Topiramate for migraine prevention: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004; 291(8): 965-973.

- Storey JR, et al: Topiramate in migraine prevention: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Headache 2001; 41(10): 968-975.

- Diener HC, et al: Topiramate in migraine prophylaxis–results from a placebo-controlled trial with propranolol as an active control. J Neurol 2004; 251(8): 943-950.

- Ashtari F, Shaygannejad V, Akbari M: A double-blind, randomized trial of low-dose topiramate vs propranolol in migraine prophylaxis. Acta Neurol Scand 2008; 118(5): 301-305.

- Keskinbora K, Aydinli I: A double-blind randomized controlled trial of topiramate and amitriptyline either alone or in combination for the prevention of migraine. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2008; 110(10): 979-984.

- Silberstein SD, et al: Efficacy and safety of topiramate for the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Headache 2007; 47(2): 170-180.

- Hering R, Kuritzky A: Sodium valproate in the prophylactic treatment of migraine: a double-blind study versus placebo. Cephalalgia 1992; 12(2): 81-84.

- Jensen R, Brinck T, Olesen J: Sodium valproate has a prophylactic effect in migraine without aura: a triple-blind, placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology 1994; 44(4): 647-651.

- Afshari D, Rafizadeh S, Rezaei M: A comparative study of the effects of low-dose topiramate versus sodium valproate in migraine prophylaxis. Int J Neurosci 2012; 122(2): 60-68.

- Institute for Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology at Charité-Universitätsmedizin Berlin. Pharmacovigilance and Embryonic Toxicology Advisory Center. 2019. www.embryotox.de, last accessed on 07/30/2019

- Parikh SK, Silberstein SD: Current Status of Antiepileptic Drugs as Preventive Migraine Therapy. Curr Treat Options Neurol 2019; 21(4): 16.

- Linde M, et al: Gabapentin or pregabalin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(6): CD010609.

- Linde M, et al: Antiepileptics other than gabapentin, pregabalin, topiramate, and valproate for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013(6): CD010608.

- Rosenfeld MG, et al: Production of a novel neuropeptide encoded by the calcitonin gene via tissue-specific RNA processing. Nature 1983; 304(5922): 129-135.

- Edvinsson L, et al: Perivascular peptides relax cerebral arteries concomitant with stimulation of cyclic adenosine monophosphate accumulation or release of an endothelium-derived relaxing factor in the cat. Neurosci Lett 1985; 58(2): 213-217.

- Goadsby PJ, Edvinsson L: The trigeminovascular system and migraine: studies characterizing cerebrovascular and neuropeptide changes seen in humans and cats. Ann Neurol 1993; 33(1): 48-56.

- Olesen J, et al: Calcitonin gene-related peptide receptor antagonist BIBN 4096 BS for the acute treatment of migraine. N Engl J Med 2004; 350(11): 1104-1110.

- o TW, et al: Randomized controlled trial of an oral CGRP receptor antagonist, MK-0974, in acute treatment of migraine. Neurology 2008; 70(16): 1304-1312.

- Ho TW, et al: Randomized controlled trial of the CGRP receptor antagonist telcagepant for migraine prevention. Neurology 2014; 83(11): 958-966.

- Dodick DW, et al: ARISE: A phase 3 randomized trial of erenumab for episodic migraine. Cephalalgia 2018; 38(6): 1026-1037.

- Goadsby PJ, et al: A Controlled Trial of Erenumab for Episodic Migraine. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(22): 2123-2132.

- Tepper S, et al: Safety and efficacy of erenumab for preventive treatment of chronic migraine: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 2 trial. The Lancet Neurology 2017; 16(6): 425-434.

- Stauffer VL, et al: Evaluation of Galcanezumab for the Prevention of Episodic Migraine: The EVOLVE-1 Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Neurol 2018; 75(9): 1080-1088.

- Skljarevski V, et al: Efficacy and safety of galcanezumab for the prevention of episodic migraine: results of the EVOLVE-2 phase 3 randomized controlled clinical trial. Cephalalgia 2018; 38(8): 1442-1454.

- Silberstein SD, et al: Fremanezumab for the Preventive Treatment of Chronic Migraine. N Engl J Med 2017; 377(22): 2113-2122.

- Detke HC, et al: Galcanezumab in chronic migraine: the randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled REGAIN study. Neurology 2018; 91(24): e2211-e2221.

- Federal Office of Public Health: Aimovig, in FOPH Bulletin. Federal Office of Public Health, Bern, 2018: 1.

- Federal Office of Public Health: Emgality, in FOPH Bulletin. Federal Office of Public Health, Bern, 2019: 1.

- Schoenen J, Sianard-Gainko J, Lenaerts M: Blood magnesium levels in migraine. Cephalalgia 1991; 11(2): 97-99.

- Ramadan NM, et al: Low brain magnesium in migraine. Headache 1989; 29(9): 590-593.

- Morris ME: Brain and CSF magnesium concentrations during magnesium deficit in animals and humans: neurological symptoms. Magnes Res 1992; 5(4): 303-313.

- Mayer ML, Westbrook GL, Guthrie PB: Voltage-dependent block by Mg2+ of NMDA responses in spinal cord neurones. Nature 1984; 309(5965): 261-263.

- Pearson PJ, et al: Hypomagnesemia Inhibits Nitric Oxide Release From Coronary Endothelium: Protective Role of Magnesium Infusion After Cardiac Surgery. The Annals of Thoracic Surgery 1998; 65(4): 967-972.

- de Baaij JH, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ: Magnesium in man: implications for health and disease. Physiol Rev 2015; 95(1): 1-46.

- Pfaffenrath V, et al: Magnesium in the prophylaxis of migraine – a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 1996; 16(6): 436-440.

- Cete Y, et al: A randomized prospective placebo-controlled study of intravenous magnesium sulphate vs. metoclopramide in the management of acute migraine attacks in the Emergency Department. Cephalalgia 2005; 25(3): 199-204.

- Chiu HY, et al: Effects of Intravenous and Oral Magnesium on Reducing Migraine: A Meta-analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Pain Physician 2016; 19(1): e97-112.

- proprietary supplement containing riboflavin, magnesium and Q10: a randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind, multicenter trial. J Headache Pain 2015; 16: 516.

- Choi H, Parmar N: The use of intravenous magnesium sulphate for acute migraine: meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur J Emerg Med 2014; 21(1): 2-9.

- Montagna P, et al: Migraine as a defect of brain oxidative metabolism: a hypothesis. J Neurol 1989; 236(2): 124-125.

- Arts WFM, et al: nadh-coq reductase deficient myopathy: successful treatment with riboflavin. The Lancet 1983; 322(8349): 581-582.

- Schoenen J, Jacquy J, Lenaerts M: Effectiveness of high-dose riboflavin in migraine prophylaxis. A randomized controlled trial. Neurology 1998; 50(2): 466-470.

- Boehnke C, et al: High-dose riboflavin treatment is efficacious in migraine prophylaxis: an open study in a tertiary care center. Eur J Neurol 2004; 11(7): 475-477.

- MacLennan SC, et al: High-dose riboflavin for migraine prophylaxis in children: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Child Neurol 2008; 23(11): 1300-1304.

- Sandor PS, et al: Efficacy of coenzyme Q10 in migraine prophylaxis: a randomized controlled trial. Neurology 2005; 64(4): 713-715.

- Ernster L, Dallner G: Biochemical, physiological and medical aspects of ubiquinone function. BBA Molecular Basis of Disease 1995; 1271(1): 195-204.

- Shoeibi A, et al: Effectiveness of coenzyme Q10 in prophylactic treatment of migraine headache: an open-label, add-on, controlled trial. Acta Neurol Belg 2017; 117(1): 103-109.

- Rozen TD, et al: Open label trial of coenzyme Q10 as a migraine preventive. Cephalalgia 2002; 22(2): 137-141.

- Slater SK, et al: A randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled, crossover, add-on study of CoEnzyme Q10 in the prevention of pediatric and adolescent migraine. Cephalalgia 2011; 31(8): 897-905.

- Granella F, et al: Migraine with aura and reproductive life events: a case control study. Cephalalgia 2000; 20(8): 701-707.

- Maggioni F, et al: Headache during pregnancy. Cephalalgia 1997; 17(7): 765-769.

- Sances G., et al: Course of migraine during pregnancy and postpartum: a prospective study. Cephalalgia 2003; 23(3): 197-205.

- MacGregor EA: Migraine in pregnancy and lactation. Neurol Sci 2014; 35(Suppl 1): 61-64.

- Calhoun AH: Migraine Treatment in Pregnancy and Lactation. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2017; 21(11): 46.

- Kaplan W, et al: Osteopenic Effects of MgS04 in Multiple Pregnancies. Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism 2006; 19(10): 1225-1230.

- U.S. Food and Drug Association: FDA Recommends Against Prolonged Use of Magnesium Sulfate to Stop Pre-term Labor Due to Bone Changes in Exposed Babies. Drug Safety Communication 2013. www.fda.gov/media/85971/download, last accessed 07/30/2019.

- Tepper D: Pregnancy and lactation – migraine management. Headache 2015; 55(4): 607-608.

- MacGregor EA: Migraine Management During Menstruation and Menopause. Continuum (Minneap Minn) 2015; 21(4 Headache): 990-1003.

- MacGregor EA: Classification of perimenstrual headache: clinical relevance. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2012; 16(5): 452-460.

- Vetvik KG, et al: Menstrual versus non-menstrual attacks of migraine without aura in women with and without menstrual migraine. Cephalalgia 2015; 35(14): 1261-1268.

- MacGregor EA, et al: Prevention of menstrual attacks of migraine: a double-blind placebo-controlled crossover study. Neurology 2006; 67(12): 2159-2163.

- MacGregor EA: Contraception and headache. Headache 2013; 53(2): 247-276.

- Shufelt CL, Bairey Merz CN: Contraceptive hormone use and cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 53(3): 221-231.

- Natoli JL, et al: Global prevalence of chronic migraine: a systematic review. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(5): 599-609.

- Straube A, et al: Prevalence of chronic migraine and medication overuse headache in Germany – the German DMKG headache study. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(2): 207-213.

- Diener HC, et al: Topiramate reduces headache days in chronic migraine: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Cephalalgia 2007; 27(7): 814-823.

- Silvestrini M, et al: Topiramate in the treatment of chronic migraine. Cephalalgia 2003; 23(8): 820-824.

- Aurora SK, et al: OnabotulinumtoxinA for chronic migraine: efficacy, safety, and tolerability in patients who received all five treatment cycles in the PREEMPT clinical program. Acta Neurol Scand 2014; 129(1): 61-70.

- Aurora SK, et al: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled analyses of the 56-week PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2011; 51(9): 1358-1373.

- Diener HC, et al: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial. Cephalalgia 2010; 30(7): 804-814.

- Dodick DW, et al: OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: pooled results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phases of the PREEMPT clinical program. Headache 2010; 50(6): 921-936.

- Yurekli VA, et al: The effect of sodium valproate on chronic daily headache and its subgroups. J Headache Pain 2008; 9(1): 37-41.

- Westergaard ML, et al: Definitions of medication-overuse headache in population-based studies and their implications on prevalence estimates: a systematic review. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(6): 409-425.

- Tassorelli C, et al: A consensus protocol for the management of medication-overuse headache: evaluation in a multicentric, multinational study. Cephalalgia 2014; 34(9): 645-655.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(5): 10-14.