Functional dyspepsia is common and severely limits quality of life. The diagnosis is initially based on a thorough medical history. If there are no accompanying alarm symptoms, empiric therapy can be initiated.

Functional dyspepsia (FD), along with irritable bowel syndrome, is one of the most common functional gastrointestinal disorders and is prevalent in the general population. The prevalence worldwide is 10-30% [1], and 2-5% of all consultations in the primary care setting are due to complaints of functional dyspepsia. With normal life expectancy, the disease leads to a sustained impairment of quality of life. Affected patients complain of persistent or recurrent upper abdominal discomfort. The diagnosis of FD is made in the absence of an organic, systemic or metabolic etiology in routine investigations. Despite many new therapeutic options, there is no uniform treatment regimen to date. The heterogeneous clinical picture and multifactorial origin of functional dyspepsia require an individual therapy management adapted to the patient.

Definition

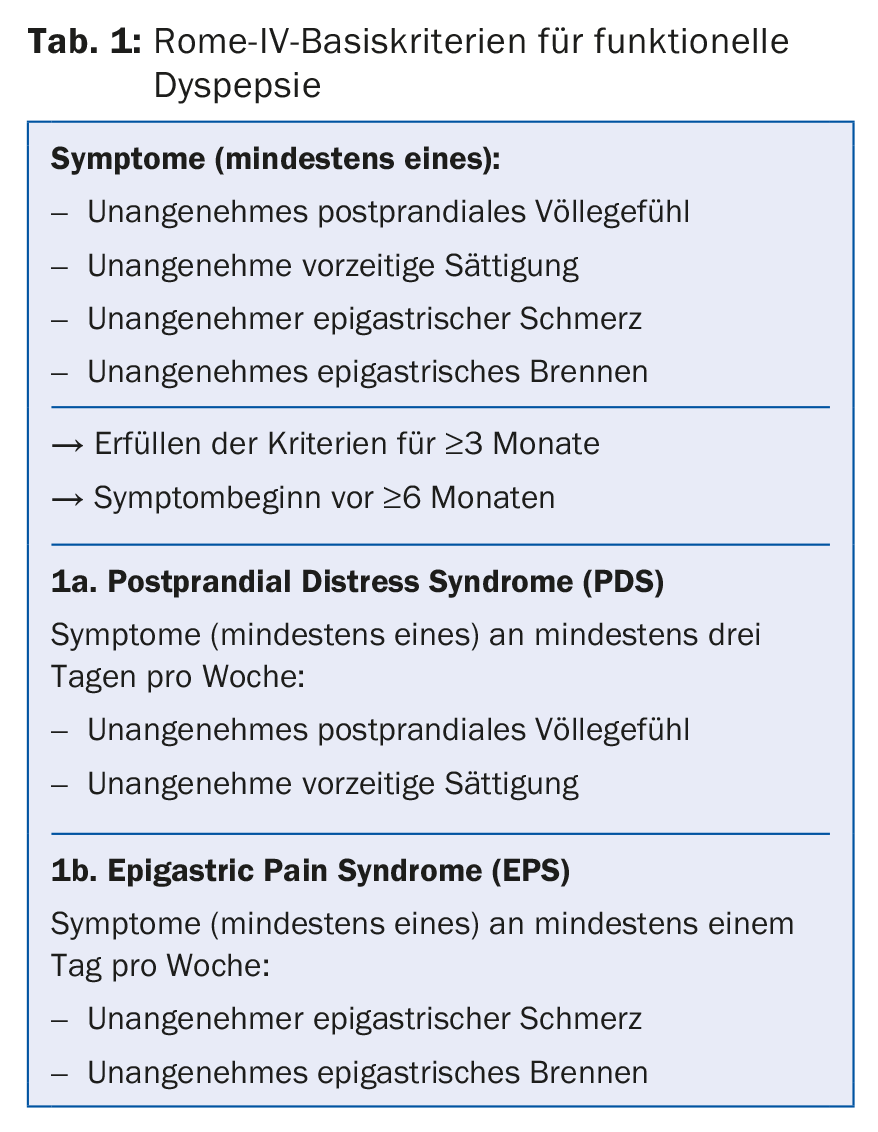

The term “dyspepsia” encompasses a symptom complex of heterogeneous upper abdominal complaints. Dyspeptic complaints that have not yet been further diagnosed are generally referred to as “dyspepsia of unclear origin”. In the absence of a diagnostically detectable organic cause, the diagnosis of “functional dyspepsia” is made. Functional dyspepsia is currently defined by the Rome IV criteria (Table 1), which divide the condition into two subgroups, postprandial distress syndrome (PDS) and epigastric pain syndrome (EPS). PDS is characterized by food-dependent symptomatology with postprandial fullness and premature onset of satiety, newly also accompanied by postprandial pain. EPS is characterized by the symptoms of epigastric pain and epigastric burning, which are not exclusively dependent on meals. Other symptoms that may occur include nausea, and less commonly vomiting, flatulence, or in a few cases weight loss.

Diagnostics

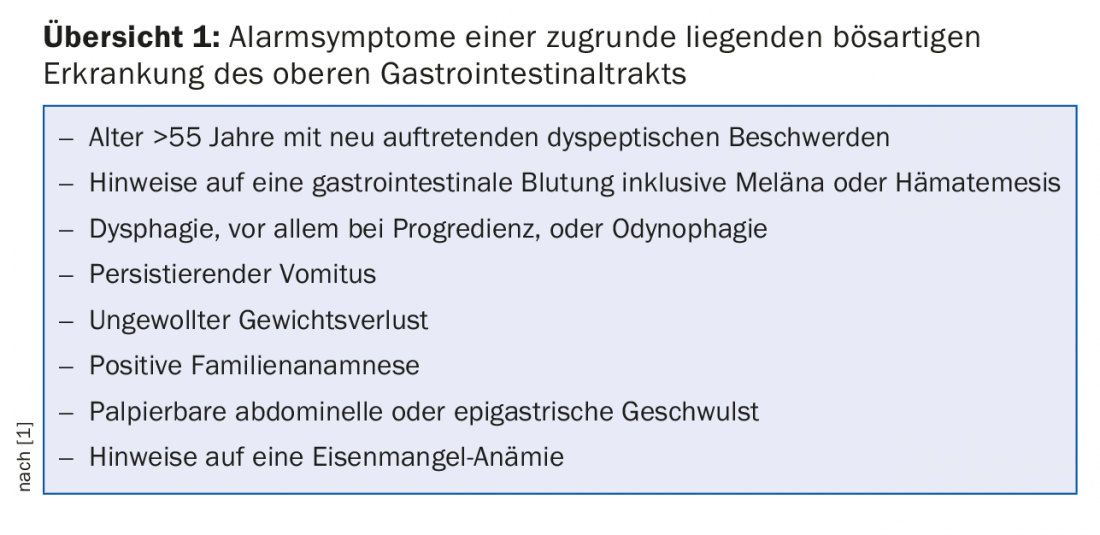

The basis of the diagnosis is a structured and precise anamnesis and the physical examination. During anamnesis, special emphasis should be placed on asking about preexisting conditions, medication use (especially NSAIDs), previous abdominal surgery, and alarm symptoms (review 1).

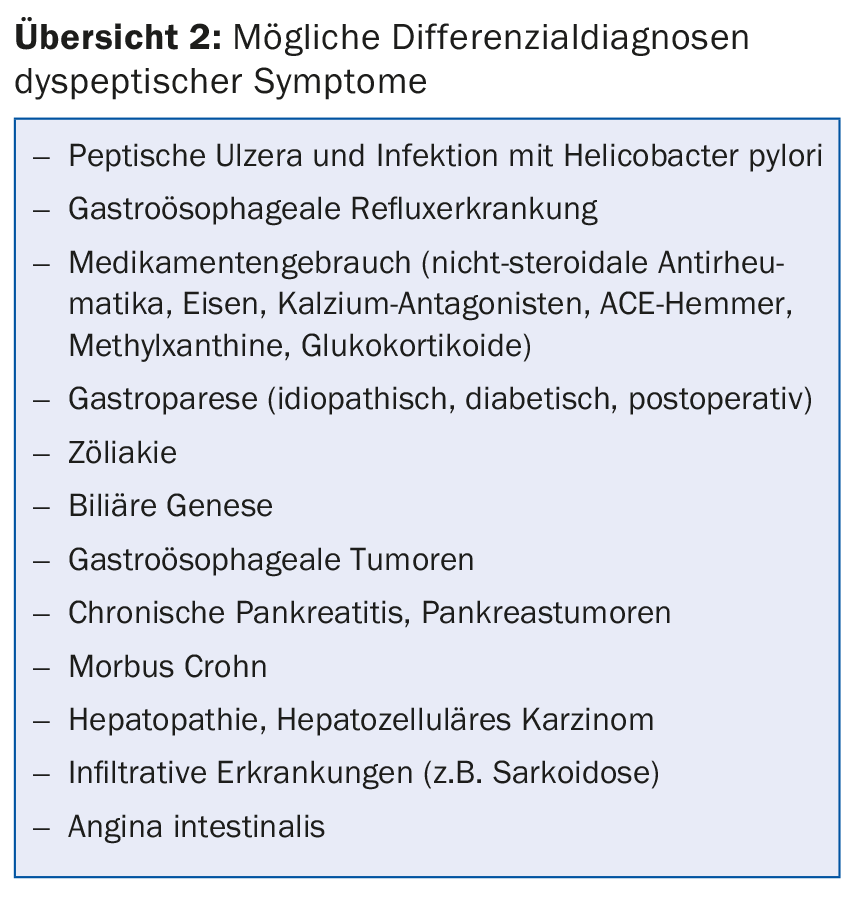

In patients with new-onset dyspeptic symptoms without alarm symptoms, empiric, symptom-based therapy can be initiated initially [1]. Unfortunately, the presence of alarm symptoms alone is not a suitable distinguishing criterion of a functional or organic genesis of dyspeptic symptoms. Therefore, to exclude the possible differential diagnoses (overview 2), a clinical examination, basic blood analysis (heme, chemistry including bili, alk Phos, P-amylase, CRP, TSH), abdominal ultrasonography, and, in most cases, esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy (ÖGD) with biopsy collection (corpus, antrum, and duodenum) should be performed as a minimum diagnostic standard before diagnosing FD.

Depending on the clinical presentation, a decision is made about further diagnostic testing. A not insignificant number of FD patients present with reflux symptoms. In these patients, acid measurement by 24-h impedance pH-metry or endoscopically inserted Bravo capsule can be performed to differentiate non-erosive gastroesophageal reflux disease (NERD). Furthermore, delayed gastric emptying can be observed in up to a quarter of those with functional dyspepsia [2]. Several diagnostic tests are available to evaluate gastric emptying disorder. The gold standard is to perform gastric emptying scintigraphy, measuring emptying time for a standardized solid test meal. The 13C breath test represents an alternative non-radioactive measurement method. Here, gastric emptying can be measured for solid and liquid test meals. Studies show that the significance of the results is comparable to that of scintigraphy [3].

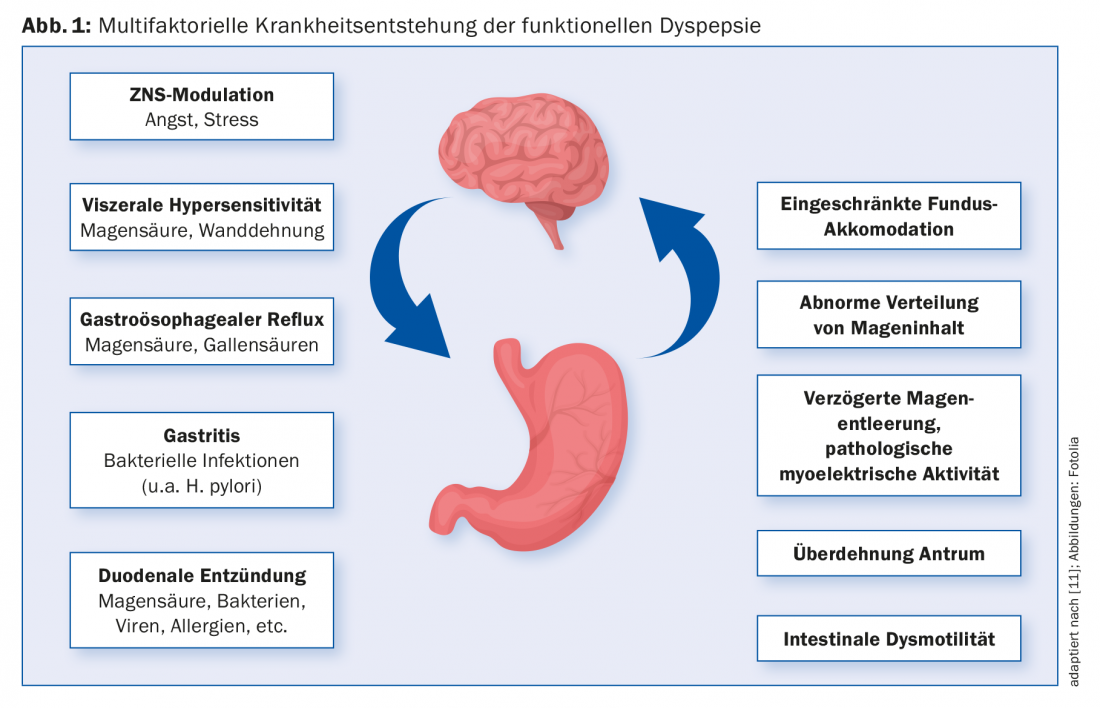

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia is multifactorial (Fig. 1). A preceding gastroenteritis is now undoubtedly recognized as a risk factor. Noroviruses, Giardia lamblia, Salmonella, Escherichia coli and Campylobacter were identified as important pathogens. The role of Helicobacter pylori infection in symptom development in functional dyspepsia is currently evaluated differently. Meta-analyses have shown that a certain proportion of FD patients benefit from H.p. eradication therapy. According to the current Kyoto consensus and the Rome IV criteria, it is now recommended to make a stand-alone diagnosis of H.p.-associated dyspepsia in patients who show sustained benefit from eradication therapy alone with regard to their dyspeptic symptoms [4]. Dyspeptic symptoms run in families. Certain genetic factors such as a polymorphism of the GNbeta C825T or CCK-AR genes are thought to play an important role. Recent studies show that psychological distress, especially anxiety disorders, is associated with FD and can both precede and follow disease onset [5]. A central role in the pathophysiology of functional gastrointestinal diseases is attributed to visceral hypersensitivity. Gastroduodenal hypersensitivity to chemical (pH, lipids) and mechanical (stretching stimuli) stimuli has been observed in patients with FD [6]. Furthermore, delayed gastric emptying [2] and impaired accommodation reflex of the gastric fundus [5] can be observed in some of the affected patients. One of the most important recent discoveries is the inflammatory response in the duodenum. This is now considered to play a key role in the development of the disease. Numerous studies have demonstrated duodenal eosinophilia and increased numbers of mast cells in patients with functional dyspepsia [7].

Therapy

The therapy of functional dyspepsia should always begin with a detailed therapy discussion. In addition to a clear diagnosis and information about the benign nature of FD (“reassurance”), it is particularly important to take the patient’s complaints seriously and not to present the disease as a harmless disorder of well-being. Patients may benefit from lifestyle changes and dietary modification. In addition to increased exercise, small regular meals, the avoidance of spicy or very fatty foods and a far-reaching renunciation of caffeine and alcohol are recommended. In addition, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided and smoking should be discontinued.

Different groups of medications are used to treat functional dyspepsia, if possible. In general, it can be recommended to select the primary drug used symptom-oriented depending on the existing subgroup.

Among the herbal medicines, Iberogast®, a phytopharmaceutical based on a combination of nine medicinal herbs, is the most important. It leads to improved gastric motility and relaxation of the fundus [8]. A large placebo-controlled trial showed significant symptom response in the drug group versus the control group. Iberogast finds great popularity among patients due to its herbal composition. We therefore recommend it as a first-line therapy and because of the virtual absence of side effects. Acid suppressive treatment with a proton pump inhibitor is widely used [9], with patients with epigastric pain syndrome benefiting more from therapy than patients in whom epigastric pain is not a dominant symptom. The proton pump inhibitor should be used in simple standard dosage, for example pantoprazole 20 mg/d, for six weeks. To prevent acid rebound, tapering of therapy may be appropriate at higher doses. In postprandial distress syndrome, patients usually benefit more initially from therapy with a prokinetic, especially if gastroparesis is present. For example, the motility-enhancing antiemetic domperidone [9] or “off-label” the enterokinetic prucalopride, which we also frequently use for constipation, can be used. Psychotropic drugs, especially antidepressants, are commonly used to treat abdominal pain in FD patients. Large prospective multicenter studies have demonstrated the superiority of the tricyclic amitriptyline over the SSRI escitalopram [10]. Visceral therapy with amitriptyline should always be initiated at a low dosage, for example 10-25 mg/d, as this is usually sufficient for pain management. In the absence of improvement after a dose increase to a maximum of 100 mg, a change in therapy is indicated.

Summary

Functional dyspepsia, popularly known as “irritable stomach”, is one of the most common gastrointestinal complaints with which patients consult their family doctor. The disease manifests itself in recurrent upper abdominal discomfort and is often associated with a significant reduction in quality of life for those affected. Due to the heterogeneous and non-specific symptomatology, finding a diagnosis is often a particular challenge. The pathogenesis of functional dyspepsia is complex and incompletely understood to date, despite important new findings in recent years. The variable symptomatology and multifactorial pathophysiology require an individual and symptom-oriented therapy management.

Take-Home Messages

- Functional dyspepsia is a common and serious condition that is associated with a significant reduction in quality of life.

- Diagnostically, a detailed anamnesis is fundamental. In cases of dyspeptic complaints without accompanying alarm symptoms, empiric therapy can be initiated; in all other cases, esophago-gastro-duodenoscopy is indicated for further clarification.

- A good doctor-patient relationship and general measures such as a change in diet and smoking cessation can lead to significant symptom recovery.

- Iberogast® (3× 20-30 drops) is an efficient and well-tolerated first-line therapy. Alternatively, sequentially or in combination, proton pump inhibitors are recommended for epigastric pain syndrome (EPS) and prokinetics for postprandial distress syndrome (PDS), depending on the subgroup.

- For refractory symptoms, visceroanalgesic therapy with low-dose amitriptyline (start 1× 10-25 mg before bedtime) can be initiated.

Literature:

- Talley N, Ford A: Functional dyspesia. N Engl J Med 2015; 373: 1853-1863.

- Haag S, et al: Symptom patterns in functional dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: relationship to disturbances in gastric emptying and response to a nutrient challenge and in consulters and non-consulters. Gut 2004; 53: 1445-1451.

- Szarka LA, et al: A stable isotope breath test with a standard meal for abnormal gastric emptying of solids in the clinic and in research. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2008; 6: 635-643.

- Fan K, Talley N: Functional Dyspepsia and Duodenal Eosinophilia: A New Model. J Dig Dis 2017; 18(12): 667-677.

- Ly HG, et al: Acute Anxiety and Anxiety Disorders Are Associated With Impaired Gastric Accommodation in Patients With Functional Dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 2015; 13(9): 1584-1591.

- Lee KJ, et al: Pathophysiology of functional dyspepsia. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2004; 18(4): 707-716.

- Vanheel H, et al: Impaired duodenal mucosal integrity and low-grade inflammation in functional dyspepsia. Gut 2014; 63(2): 262-271.

- Pilichiewicz AN, et al: Effects of iberogast on proximal gastric volume, antropyloroduodenal motility and gastric emptying in healthy men. Am J Gastroenterol 2007; 102(6): 1276-1283.

- Moayyedi P, et al: Pharmacological interventions for non-ulcer dyspepsia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; (4): CD001960.

- Talley N, et al: Effect of amitriptyline and escitalopram on functional dyspepsia: a multicenter, randomized controlled study. Gastroenterology 2015; 149: 340-349.

- Stangehellini V, et al: Gastroduodenal Disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; 150: 1380-1392.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(2): 15-19