The prevalence of asthma in children has steadily increased in recent decades. Today, it is one of the leading causes of chronic disease at a young age. Some small studies have already suggested that low-level exposures to irritants in cleaning products can cause chronic inflammation and trigger asthma symptoms.

Young children, who spend 80-90% of their time indoors in the early years, are at particular risk because of their increased respiratory rate and proximity to the ground, where exposure to gases and skin is increased. Researchers from Simon Fraser University in Vancouver wanted to get to the bottom of the link between the frequency of cleaning product use in early infancy (3-4 months) and childhood asthma or its precursors by age 3. For this purpose, they evaluated data from the Canadian Healthy Infant Longitudinal Development (CHILD) cohort study.

Included were 2022 children who had been followed from birth to three years of age. When the infants were between 3 and 4 months old, parents were required to complete a questionnaire on exposure to household cleaning products and how often certain types of products were used. Asthma diagnosis, atopy, recurrent wheezing, and a combination of recurrent wheezing and atopy at 3 years of age were studied. A child was classified as having asthma if the parents answered “yes” to the corresponding question on the questionnaire thereafter or if the asthma was personally diagnosed by a CHILD clinician during the 3 years.

Because asthma diagnosis is often difficult or unreliable in 3-year-olds, the researchers included additional parameters. Among others, atopic status was determined by skin testing for 13 inhalant and 4 food allergens. A child was considered to have recurrent gieating if he or she had two or more seizures of at least 15 minutes duration in the previous 12 months. Early childhood wheezing, especially when recurrent and accompanied by atopy, is an important predictor of future risk for asthma in children with abnormal airway function and a higher response to environmental exposures during life.

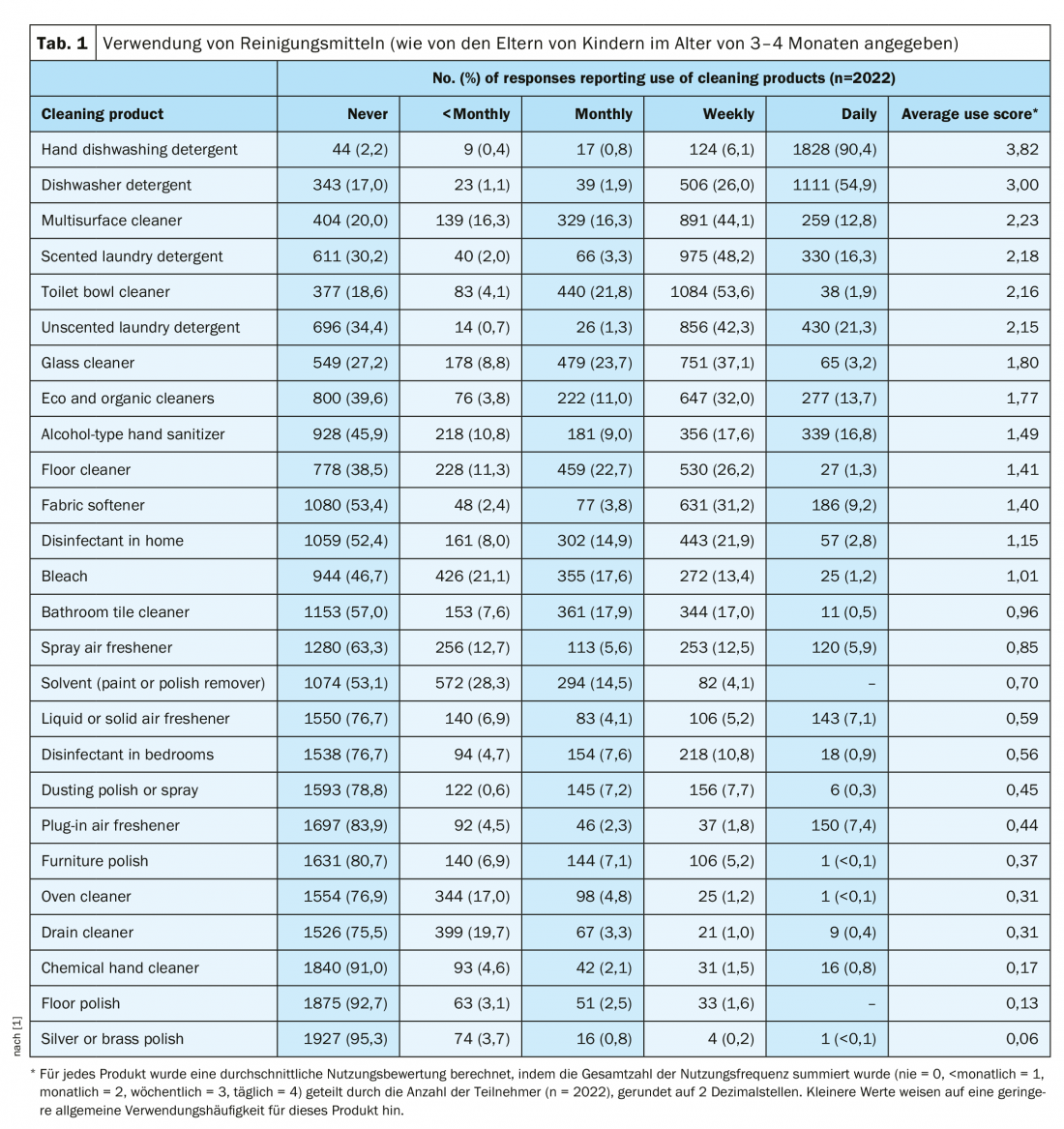

76.4% of participants had not experienced tobacco smoke exposure (n=1545) by 3 to 4 months of age, and a parental history of asthma was also predominantly absent (64.7%). Pets were present in 57% of homes, and visible mold was observed in 41.9% of homes. The most commonly used products were hand dishwashing detergent, dishwashing detergent, floor cleaner, glass cleaner, and laundry detergent (Table 1).

Increased risk for asthma, but not for atropia alone

Analysis of exposure frequency showed nonsignificant trends toward associations with recurrent wheezing (adjusted OR 1.26; 95% CI 0.85-1.88), recurrent wheezing with atopy (adjusted OR 1.76; 95% CI 0.81-4.06), and asthma (adjusted OR 1.57; 95% CI 0.98-2.53), but not with atopy alone (adjusted OR 1.17; 95% CI 0.85-1.63) compared with participants with low exposure frequency. Girls were more affected than boys. The risk was increased especially for children in whose households liquid or solid air fresheners, spray air fresheners, plug-in deodorizers, dust sprays, antimicrobial hand sanitizers, and oven cleaners were frequently used.

The lack of an association between detergents and atopy is consistent with previous research. A 2015 longitudinal study found that exposing children to volatile organic compounds at a very young age increases the risk of atopic dermatitis by age 3. Allergic sensitivities, however, still develop in childhood, and frequent use of cleaning products can hinder indoor growth and contact with microbes, which are necessary to strengthen the immune system and protect against allergic diseases. Researchers suspect that chemicals in cleaning products damage airway epithelium by affecting inflammatory pathways of the innate immune system. The resulting inflammation leads to airway hyperresponsiveness, which can become chronic and result in allergic sensitization.

Their findings, the researchers concluded, were not evidence but did suggest that effects on the respiratory tract early in life from frequent use of cleaning products are more likely due to an inflammatory than an acquired allergic response. The potential for these common household products to predispose the respiratory system to future allergic reactions is an area of future investigation, he said.

Literature:

- Parks J, et al: CMAJ 2020; 192 (7): E154-E161; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.190819

InFo PNEUMOLOGY & ALLERGOLOGY 2020; 2(2): 24-25.