If thromboembolism is not detected and treated in time, life-threatening consequences may result. Validated tests, such as the Wells score and the D-dimer test, can be used to assess the risk of thrombosis. In recent years, anticoagulants (DOAK) have become established as an alternative to vitamin K antagonists for the treatment and prophylaxis of thrombosis. Thus, the current ASH guidelines also recommend anticoagulation with DOAK for patients with deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism.

Leg vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism are both manifestations of venous thromboembolism. Pulmonary embolism is one of the most dangerous complications of thrombosis. The incidence of venous thromboembolism is age-dependent. In 20- to 40-year-olds, the annual incidence of leg vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism is 1:1000, whereas in those older than 75, this value is 1:100 [1]. The Virchow triad describes three major factors leading to the development of thrombosis: Endothelial lesion, changes in flow velocity (hypocirculation, stasis), coagulation disorders (hypercoagulability). Typical predisposing factors include surgery, cancer, or hospitalization. Risk factors specific to women are pregnancy, puerperium, and use of the pill or hormone replacement therapy.

Which patients are at increased risk for pulmonary embolism?

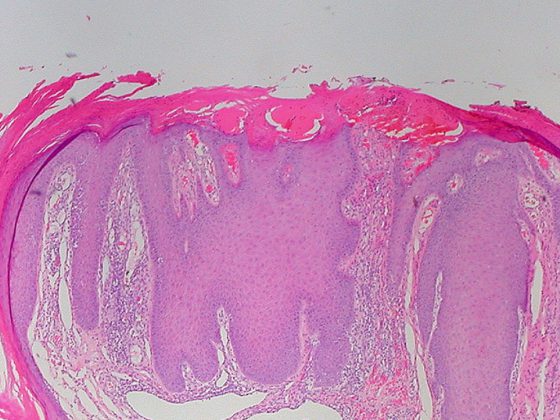

“When we think of pulmonary embolism, we have to look for it,” because many symptoms, such as dyspnea, chest pain, or cough, are nonspecific, says Prof. Christina Jeanneret-Gris, M.D., Senior Physician, Baselland Cantonal Hospital, Bruderholz [2]. “We especially need to know, based on experience, which patients are ‘at risk,'” the expert says, emphasizing, “Ask about effort dyspnea.” The experience of the treating physician is important; in addition, there are several empirically validated methods that can be used to support the clinical assessment. According to the American Society of Hematology (ASH) guidelines published in 2020, clinical assessment cannot be replaced by scores to predict patient outcomes, but these can provide additional guidance [3]. The D-dimer and Wells score act as supportive tools for predicting pulmonary embolism (Fig. 1). Elevated D-dimers alone are not an indication for anticoagulation [5]. D-dimers are formed as cleavage products from fibrin and indicate increased coagulation and fibrinolysis activity of any genesis, i.e., in addition to thrombotic reactions, also nonspecific reactions such as inflammation, trauma, surgery, pregnancy, active tumor disease, or bleeding/hematoma formation.

D-dimer test plus Wells score: high negative predictive value.

Adding the Wells score can significantly increase the negative predictive probability of the D-dimer test. According to a prospective study published in 2019 in the New England Journal of Medicine, pulmonary embolism can be largely excluded in “low-risk” patients at a D-dimer <1000 µg/ml in combination with a Wells score <4 [6].

Of 1325 patients with low or moderate pretest probability and negative D-dimer test (<1000 µg/ml), none developed venous thromboembolism during the three-month follow-up period. Study participants did not receive anticoagulants during this period. In summary, a cut-off <1000 µg/ml is generally valid for the D-dimer, but it is important to note that the D-dimer has to be interpreted age-dependently, Prof. Jeanneret-Gris mentioned in addition (box).

If the D-dimer test is positive, imaging is subsequently required to confirm the suspected thrombosis; if the findings are unclear, a follow-up examination after a few days is recommended [5]. Regarding the choice of imaging modality, leg vein ultrasonography is recommended if deep vein thrombosis is suspected; if pulmonary embolism is suspected, pulmonary scintigram or CT angiography is recommended.

Taking advantage of direct oral anticoagulants (DOAKs)

If pulmonary embolism is detected, anticoagulant therapy should be started immediately. To help decide whether a pulmonary embolism patient can be treated in the outpatient setting, there is the PESI (“The Pulmonary Embolism Severity Index”), a multiply validated score for risk stratification of pulmonary embolism sufferers (Table 1) [4]. Prompt anticoagulation is also recommended in cases of deep vein thrombosis to prevent further growth of the thrombus and washing into the pulmonary circulation. Which drug is best suited for which patient or has the most optimal individual benefit-risk profile is decided on a case-by-case basis by the general practitioner or the treating specialist.

The effect of the direct oral anticoagulants (DOAK) is more rapid than that of the vitamin K antagonists and subsides correspondingly more quickly. With reliable and regular daily use, the risk of embolism from DOAK treatment can be significantly reduced and the risk of bleeding is comparatively low. “The new direct anticoagulants act mainly on factor Xa, but also on factor IIa,” Prof. Jeanneret-Gris said. The following DOAKs are currently approved in Switzerland: Rivaroxaban (Xarelto®), Apixaban (Eliquis®), Edoxaban (Lixiana®), Dabigatran (Pradaxa®) (Tab. 2) [7].

The current ASH guidelines do not specify which active substance is particularly suitable in which clinical situation. Prof. Jeanneret-Gris uses rivaroxaban and edoxaban in carcinoma patients and apixaban in patients with renal insufficiency, among others. In patients with co-medication (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants), she often prescribes edoxaban. With rivaroxaban and apixaban, more attention would need to be paid to co-medications due to CYP3A4 interactions, which was less of a concern with dabigatran and edoxaban. Regarding the duration of primary anticoagulant therapy, according to current ASH guidelines, a period of 3-6 months is preferable to a longer treatment duration.

For secondary prophylaxis, the American Society of Hematology suggests longer-term continuation of DOAK treatment for an indefinite period in idiopathic thromboembolism, with standard or low dosing (eg, rivaroxaban 10 mg/1×d, apixaban 2.5 mg/2×d).

Stop aspirin during DOAK therapy

Further advice from the current ASH guideline is as follows [3]: If thrombosis occurs during anticoagulation with a vitamin K antagonist (e.g., Marcoumar), a low-molecular-weight heparin should be given and not a DOAK. Recurrent thromboembolism requires longer-term coagulative treatment. And very important, he said, is to stop aspirin when giving a DOAK. Prof. Jeanneret-Gris always does this, except when a recent coronary event (e.g., stent, myocardial infarction) has occurred. According to ASH guidelines, the use of compression may be omitted, noting that compression stockings can help reduce edema and pain. In the acute stage of thrombi, the speaker finds compression quite useful, and the benefit has also been empirically proven.

Congress: FomF Advanced Training Days Family Physician 2021

Literature:

- DGA: Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism, www.dga-gefaessmedizin.de (last accessed Oct. 21, 2021).

- Jeanneret-Gris C: Venous thrombosis, Prof. Christina Jeanneret-Gris, MD. FomF Training Days Family Physician, 08./09.09.2021

- Ortel TL, et al: American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: treatment of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism. Blood Adv 2020; 4 (19): 4693-4738.

- Jimenez D, et al: Simplification of the pulmonary embolism severity index for prognostication in patients with acute symptomatic pulmonary embolism. Arch Intern Med 2010; 170 (15): 1383-1389.

- Medix: Thromboembolism, www.medix.ch/wissen/guidelines/herz-kreislauf-krankheiten/thromboembolie (last accessed Oct. 21, 2021).

- Kearon C, et al: Diagnosis of pulmonary embolism with D-dimer adjusted to clinical probability. N Engl J Med 2019; 381: 2125-2134.

- Drug information: www.compendium.ch (last accessed Oct 21, 2021).

- Rhigini M, et al: JAMA 2014; 311(11): 1117-1124.

- Nuremberg Hospital: Acute Pulmonary Embolism, University Department of Internal Medicine, www.klinikum-nuernberg.de (last accessed Oct. 22, 2021)

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(11): 24-26 (published 11/15-21, ahead of print).