Somatoform disorders do occur frequently and are relevant to health economics. Nevertheless, they are still sometimes given little attention in psychiatry and psychotherapy – both in clinical care and in research. Reasons for this situation include the fact that the term “somatoform disorder” was not introduced into official classification systems until 1980, and the term describes a very inhomogeneous group of patients. So far, it is questionable whether the different clinical pictures represent a nosologically uniform concept.

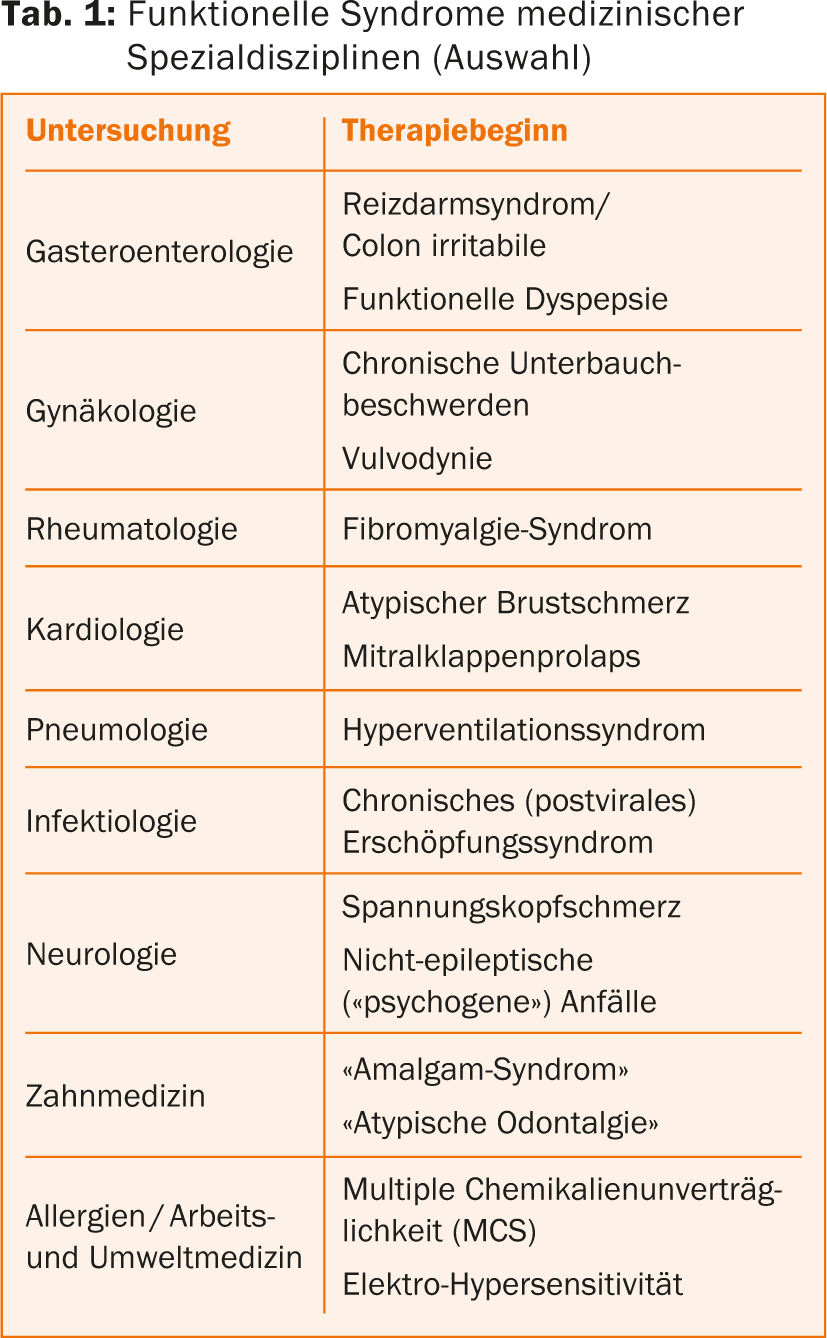

Somatoform disorders have an exceptional position in psychiatric diagnostics, since in many cases they do not appear clinically under this medical term. The German S3 guideline “Management of patients with non-specific, functional and somatoform body complaints (NFS)”, which is primarily aimed at general practitioners and somatic specialists, lists a large number of medical functional terms, behind which a somatoform disorder is often hidden [1]. Well-known disorders are fibromyalgia syndrome or chronic fatigue syndrome, but also lesser-known syndromes such as glossodynia (burning tongue) or bruxism ( tab. 1).

Phenomenologically, the clinical pictures subsumed under “somatoform disorders” correspond to what used to be understood as functional disorders in the German-speaking world [2]. However, the two terms are not completely congruent. Quite a few patients with functional syndromes do not meet the criteria for a diagnosis of somatoform disorder [3]. In the English literature, the term “medically unexplained symptoms” (MUS or MUPS) is more commonly used as an umbrella term for the various disorders, although the concept has also been criticized for its vagueness [4].

Definitions and criteria

The characteristic feature of all somatoform disorders, according to ICD-10 [5,6] and DSM-IV [7], is the presence of physical discomfort or anxiety that cannot be fully explained by a physical finding, substance exposure, or by another mental disorder. The problem with this definition is that it does not explain the core symptoms of the disorder, which reduces the reliability and validity of the diagnoses. Moreover, it was shown that the diagnosis of the core disorder of the somatoform disorder group, somatization disorder, is very rarely assigned due to much too complex diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV, whereas undifferentiated somatoform disorder has much too unspecific criteria [8]. Primarily because of this problem, the DSM-5 [9] completely abandoned the divergence between somatic findings and somato-psychic complaints in the definition of somatoform disorders, and the individual disorders were conceptually redefined as follows (Tab. 2). The focus of the diagnostic criteria in DSM-5 is no longer the absence of a medical cause for the complaints as in DSM-IV-TR, but a single somatic symptom is sufficient, with the following requirement: “excessive thoughts, feelings, or behaviors are related to the somatic symptoms or associated health concern” [9]. The various problems of the absence of such a distinction (medically explainable vs. unexplainable) cannot be addressed in this framework [10]. However, an initial study validated the inclusion of psychological and behavioral features in the DSM-5 diagnosis of somatoform disorders [11].

The diagnostic criteria of the individual disorder patterns in somatoform disorders are only listed in the ICD-10 research criteria [5], but not in the clinical diagnostic guidelines [6]. Only very glossary-like descriptions are reproduced in the clinical diagnostic guidelines. Therefore, clinically active colleagues should base their diagnosis on the research criteria, which largely correspond to the DSM-IV7 criteria (Table 3).

Comorbidity and epidemiology

Depressive disorders and anxiety disorders are the main differential diagnoses. At the same time, these two groups of disorders are also the most common comorbid disorders. Approximately 50% of patients with somatoform disorders also have a depressive disorder, and 45-95% of patients with depression also have somatic symptoms at the time of diagnosis. Similar rates of comorbidity exist to anxiety disorders [12]. In a Europe-wide analysis, somatoform disorders represented the fourth most common mental disorder with a 12-month prevalence rate of 6.3% [13]. Somatoform pain disorders are the most common separate diagnostic group [14]; they incur comparable costs to anxiety disorders and depressive disorders [15].

Pathophysiology and nosological concepts

The pathophysiology of somatoform disorders is poorly understood. It is not even clear whether the group of somatoform disorder syndromes, which includes conditions as diverse as irritable bowel syndrome or hyperventilation syndrome, constitutes a unified disorder group. However, some chronic MUPS have been shown to be disproportionately common together and associated with identical factors (female gender, high health anxiety, history of traumatic events) [16]. A meta-analysis identified an association between a history of sexual abuse and several functional (but not all) complaints [17].

A genetic disposition to somatoform disorders has been demonstrated [18]. However, this is weaker than in other mental disorders such as schizophrenia. The concordance rate was 29% for identical twins and 10% for fraternal twins. However, all concordant pairs had different somatoform disorders or other psychiatric disorders, so additional environmental influence is likely.

Currently, the most elaborate model for explaining somatoform disorders is based on the concepts of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) [12]. The psychological disorder model of CT addresses the psychological processes that are pathologically altered in somatoform complaints and lead to dysfunctional illness behavior, which in turn contributes significantly to the chronification of symptoms [12]. At the same time, the disturbance model allows the identification of the processes that are used as intervention strategies within the framework of CT (Fig. 1).

Therapy options

One of the biggest therapeutic obstacles in treating patients with somatoform disorders is their “organically fixed” model of illness. Developing a psychophysiological understanding is a major goal of treatment [12]. Clinical experience repeatedly shows that in patients with somatoform disorders, communication between all medical (psychiatrist, internist, orthopedist, etc.) and psychotherapeutic practitioners is a key criterion for successful therapy.

Pharmacotherapy

Overall, very few empirical studies exist on the efficacy of psychotropic drugs in somatoform disorders, so their use must be critically questioned. According to the S3 guideline, psychopharmacological treatment with antidepressants should only be given in cases of pain-dominant symptoms (e.g., fibromyalgia syndrome) or a comorbid depressive disorder [1]. However, there is insufficient data to support differential efficacy of individual antidepressant classes, although there is own positive experience with the use of amitriptyline.

Medications to improve somatic symptoms should be used after a critical risk-benefit assessment and for a limited time. Equally critical is the use of antipsychotics, opioid analgesics, or benzodiazepines [1].

Psychotherapy

CT is the gold standard of treatment for somatoform disorders. In addition to this evidence, some empirical evidence exists, albeit to a much lesser extent, for the efficacy of psychodynamic therapies for individual functional syndromes. Table 4 summarizes the findings of evidence-based guidelines on psychotherapy for somatoform disorders and associated syndromes [19].

With regard to efficacy, it must be noted that the effect sizes are low to moderate, so that ultimately only an improvement in symptoms is achievable, but often not a complete remission.

Generally speaking, the approach to CT includes the following components [19]:

- Extension of the subjective disorder model, attempting to identify other possible influencing factors in addition to organic explanations.

- Based on a symptom diary, patients are motivated to reduce physical states of tension using relaxation techniques.

- Changing the focus of attention with the goal of reducing the patient’s focus on physical complaints.

- Reduction of dysfunctional cognitions: Many patients show generalized and catastrophizing evaluations (chest pain is always a sign of a heart attack); alternative views need to be developed.

- Reduction of protective behavior: Many patients show pronounced protective behavior. The goal is to build adequate physical resilience.

Various manuals and descriptions of the psychotherapeutic approach to somatoform disorders and functional physical symptoms exist, mainly based on CT [19]. Individual manuals have a very flexible structure so that the therapy modules can be individually adapted to the patient’s complaint profiles [20].

Practical tips for practitioners

- Confirm the credibility of the complaints and work out a common model of disturbance with your patients.

- Assign regular and fixed but time-limited appointments that are not complaint-driven.

- Critically question inadequate sparing behavior and motivate patients to increase activity in a staged manner.

- The therapies of all medical and psychotherapeutic practitioners involved should be coordinated and concerted.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the therapeutic gold standard; CBT techniques are integrated into outpatient treatment.

- Reluctance to use psychotropic drugs in general and specifically opioid analgesics or benzodiazepines.

Literature:

- Hausteiner-Wiehle C, et al. (Eds.): S3 guideline “Management of patients with non-specific, functional and somatoform body complaints”. Schatthauer, Stuttgart 2013.

- Langewitz W: In Adler RH, et al. (Ed.). Munich Elsevier 2011; 739-775.

- Hausteiner-Wiehle C, Henningsen P: World J of Gastroenterology 2014; 20: 6024-6030.

- Isaac ML, Paauw DS: Med Clin N Am 2014; 98: 663-672.

- Dilling H, et al: International classification of mental disorders. ICD-10 chapter V (F) research criteria. Huber, Bern 1994.

- Dilling H, et al: International classification of mental disorders. ICD-10 chapter V (F) clinical diagnostic guidelines. Huber, Bern 1993.

- Saß H, et al: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-IV. Hogrefe, Göttingen 1996.

- Dimsdale JE, et al: J Psychosomatic Research 2013; 75: 223-228.

- American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder. Washington D.C.: Am Psychiatr Pub 5th Edition 2013.

- Rief W, Martin A: Annu Rev Clin Psychol 2014; 10: 339-367.

- Wollburg E, et al: Journal Psychsomatic Research 2013; 74: 18-24.

- Rief W, Hiller H: Somatization disorder. 2nd ed. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2011.

- Wittchen HU, et al: Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 2011; 21: 655-679.

- Grabe HJ, et al: Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics 2003; 72: 88-94.

- Konnopka A, et al: Psychother Psychosom 2012; 81: 265-275.

- Aggarwal VR, et al: Internat J Epidemiology 2006; 35: 468-476.

- Paras ML, et al: JAMA 2009; 302: 550-561.

- Torgersen S: Arch Gen Psychiatry 1986; 43: 502-505.

- Martin A, et al: Evidence-based guideline on psychotherapy for somatoform disorders and associated syndromes. Hogrefe, Göttingen 2013.

- Kleinstäuber M, et al: Cognitive behavioral therapy for medically unexplained body complaints and somatoform disorders. Springer, Berlin 2012.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(5): 26-31.