Anxiety disorders, along with depression, are among the most common mental illnesses. It is not uncommon to see the doctor primarily for physical symptoms, such as palpitations, shortness of breath, dizziness, and gastrointestinal discomfort. Correct diagnosis and initiation of adequate treatment are essential to prevent generalization and chronification of anxiety symptoms. The therapy of choice is cognitive behavioral therapy including exposure-response management. Drug therapy should be considered if the patient is severely impaired and cognitive behavioral therapy alone has not produced the desired effect.

Both ICD-10 and DSM-5 distinguish object- and situation-dependent (phobic) from object- and situation-independent fears.

- In a phobic disorder, the affected person feels fear predominantly or exclusively in narrowly circumscribed, actually harmless situations. Outside of these anxiety situations, there is typically freedom from symptoms. However, fear of anxiety, as well as avoidance of anxiety-provoking situations, can have a lasting impact on quality of life.

- In the context of object- and situation-independent anxiety, the anxiety symptoms occur suddenly without any external specific cause (panic disorder) or are characterized by permanent tension and fear (generalized anxiety disorder).

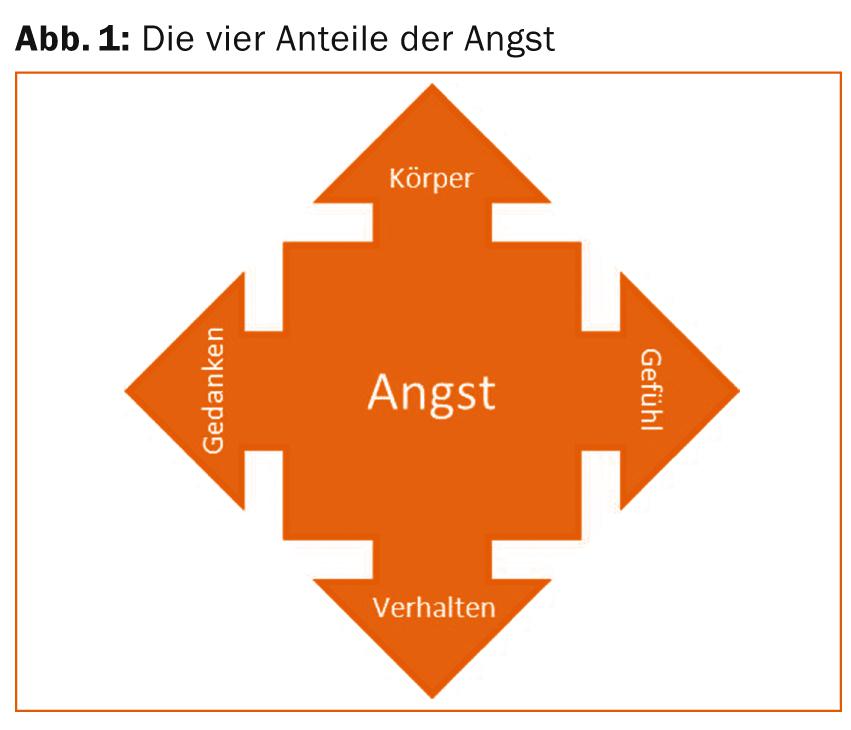

An important part of the analysis of anxiety symptoms is the detailed recording of all four parts of anxiety [1]. These four shares are

- the physical symptoms

- the thoughts and feelings that accompany the fear

- Feelings as well as

- the behavior.

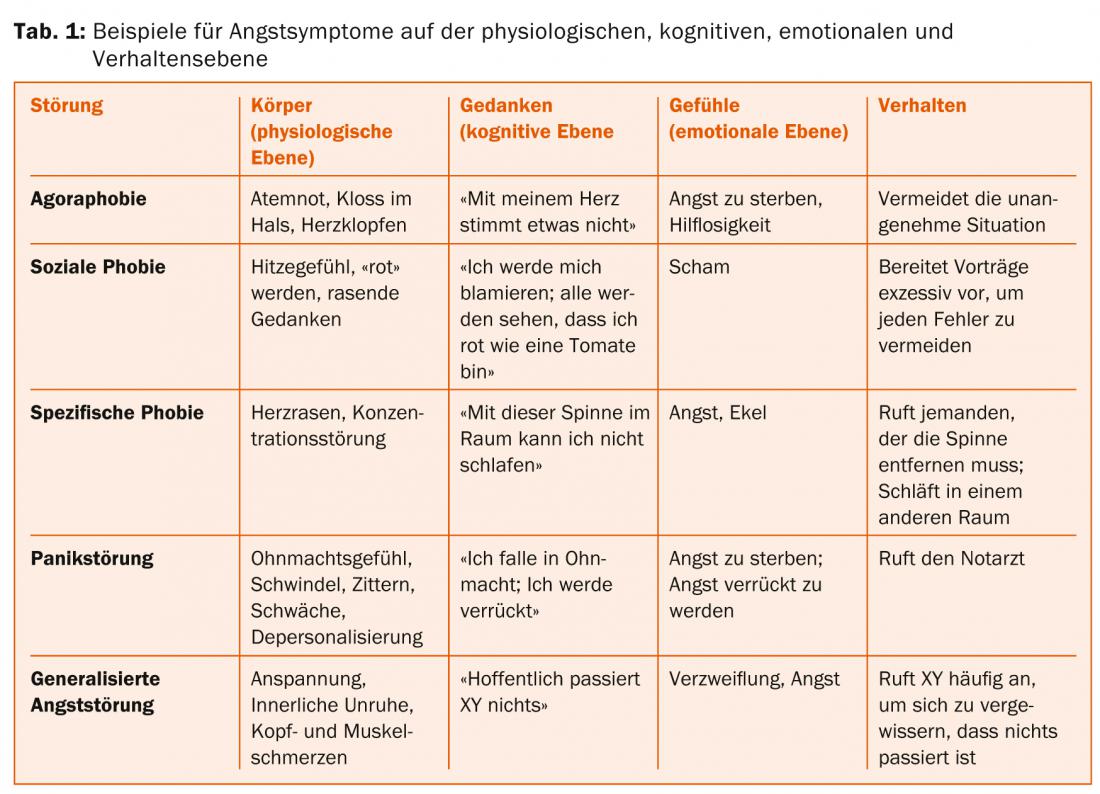

Figure 1 summarizes the proportions, and Table 1 presents examples of the four anxiety proportions of the major anxiety disorders.

Characteristics

Characteristic of each anxiety disorder are the following aspects:

Agoraphobia: Fears sometimes exist when using public transportation, in enclosed spaces and crowds. In some cases, patients can only leave the house if they are accompanied. Physical symptoms are often complained of as well.

Social phobia: There is a pronounced fear of being judged negatively in social situations due to one’s own behavior or due to the occurrence of feared symptoms (e.g., “blushing”). Appropriate situations (e.g. giving a lecture, attending a birthday party) are therefore avoided or endured only with strong anxiety.

Specific phobia: Typically, anxiety symptoms occur only when the sufferer is confronted with the specific, triggering stimulus (e.g., elevator in claustrophobia). Outside of trigger situations, affected individuals are symptom-free. Depending on the occurrence of the trigger event, symptom-free intervals may last several weeks or months. In terms of content, these phobias can relate to any life situation (e.g., flying, darkness, individual animals, etc.).

Panic disorder: Patients with panic disorder suffer from intermittent severe anxiety attacks (panic), which are unpredictable for the patient and often accompanied by the fear of dying. These attacks start abruptly and reach their maximum within a short time. Patients with panic disorder often complain of physical symptoms and repeatedly visit physicians/emergency departments because of them. The examinations performed (e.g. ECG, laboratory) typically remain without pathological findings.

Generalized Anxiety Disorder: The focus of this disorder is permanent worry about numerous issues in everyday life. Other significant symptoms include muscle tension (often accompanied by acute and chronic pain), restlessness, nervousness, irritability, and sleep disturbances.

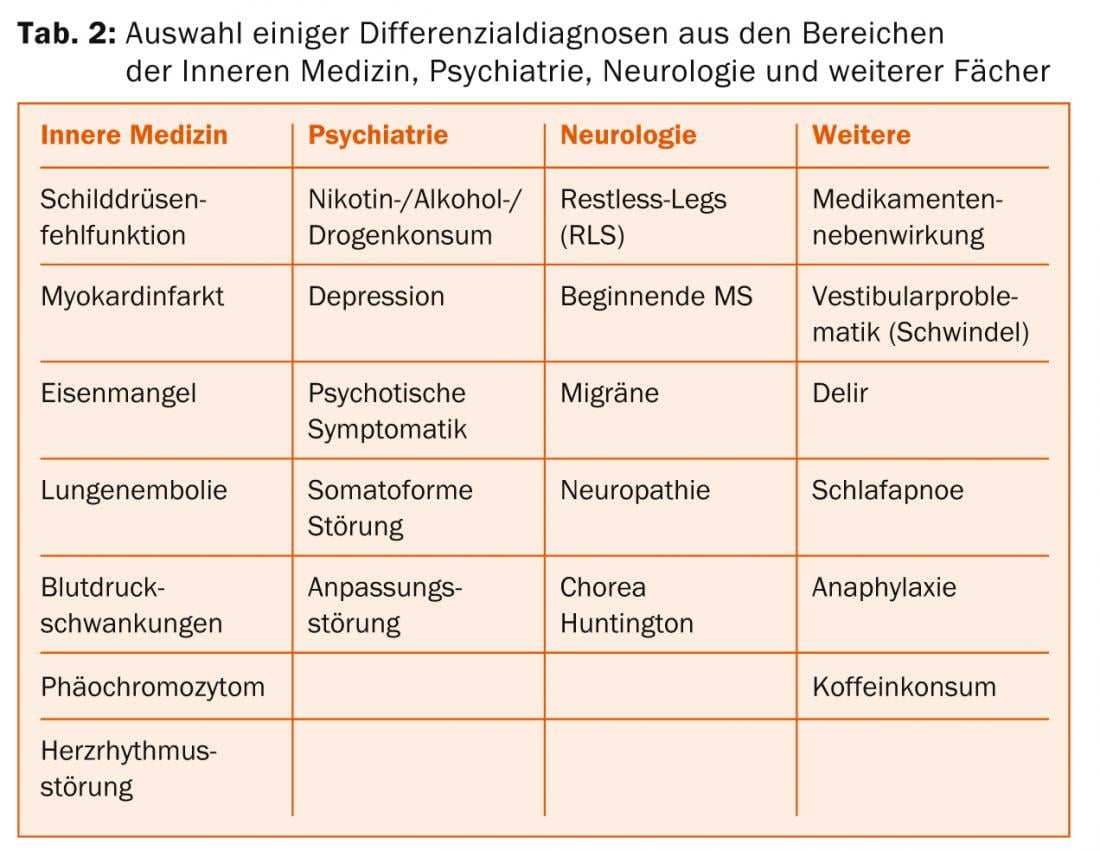

Before an anxiety disorder is diagnosed, physical causes and diseases that can cause anxiety and anxiety-like symptoms must be ruled out. The key points here are a good medical history (including medication and substance history) as well as a basic physical examination and technical clarifications, such as ECG, blood pressure measurements and basic laboratory including thyroid values. Typical differential diagnoses are summarized in Table 2.

Neurobiological basics

The amygdala or tonsil nucleus, located medially in the temporal lobe, is the brain region thought to play a central role in threat detection. Once the amygdala has “perceived” a stimulus as threatening, regions located in the midbrain and brainstem are activated, which then trigger the typical physiological symptoms of anxiety: Increase in respiratory and heart rate and blood pressure, muscular tension, sympathetic tone, activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenocortical system (cortisol), and others. In parallel, other cognitive systems responsible for perceiving and processing stimuli are affected: attention and thinking are focused on potentially threatening stimuli, other content recedes into the background. On the neurobiological level, these two processes (peripheral-physiological, cognitive) are reflected in increased activations in the insular cortex on the one hand and in prefrontal and parietal cortical regions on the other.

Such a fear response is regularly found when healthy individuals are confronted with fear-inducing stimuli. How strongly a healthy person reacts depends, among other things, on individual anxiety, i.e., the individual tendency to perceive situations and stimuli as threatening and to react with fear. The more anxious a person, the more likely a fear response will be triggered and the stronger the fear response. From a neurobiological perspective, the same systems are involved in appropriate “normal” anxiety and in anxiety disorders. In anxiety disorders, however, these systems are involved to a greater extent and they respond to stimuli and situations that do not elicit a fear response in healthy individuals. Thus, increased activity and reactivity of the amygdala (Fig. 2), insular cortex, and in frontal regions is generally found in anxiety disorders [2,3]. With successful therapy, this hyperactivity decreases to normal [4].

Therapy

Once the possible physical diseases have been ruled out, further somatic investigations should be avoided as far as possible, since these reinforce the (often hypochondriacal) fears and delay the start of adequate therapy [5]. Psychoeducation has a high priority in the initial discussions, which often take place at the family doctor’s office or (in the case of panic attacks) in the emergency ward. The patient’s complaints should be explained as symptoms of stress or anxiety that can be well treated.

Concrete guidance for self-help plays an important role in all degrees of severity of anxiety disorders, and may even be sufficient in cases of mild symptomatology without relevant restriction of everyday activities. In practice, it has proven effective to counsel patients individually and to systematically instruct them in coping with anxiety by including cognitive-behavioral self-help literature (bibliotherapy) [6]. This can be used to convey in a structured way the cycles through which anxiety is triggered and maintained and the possibilities that exist for interrupting them and overcoming anxiety. Relaxation techniques such as Jacobson’s progressive muscle relaxation are also used. The information that functional brain changes have been demonstrated in people with anxiety disorders and that these normalize when anxiety is successfully managed can be relieving and motivating for active management of anxiety problems.

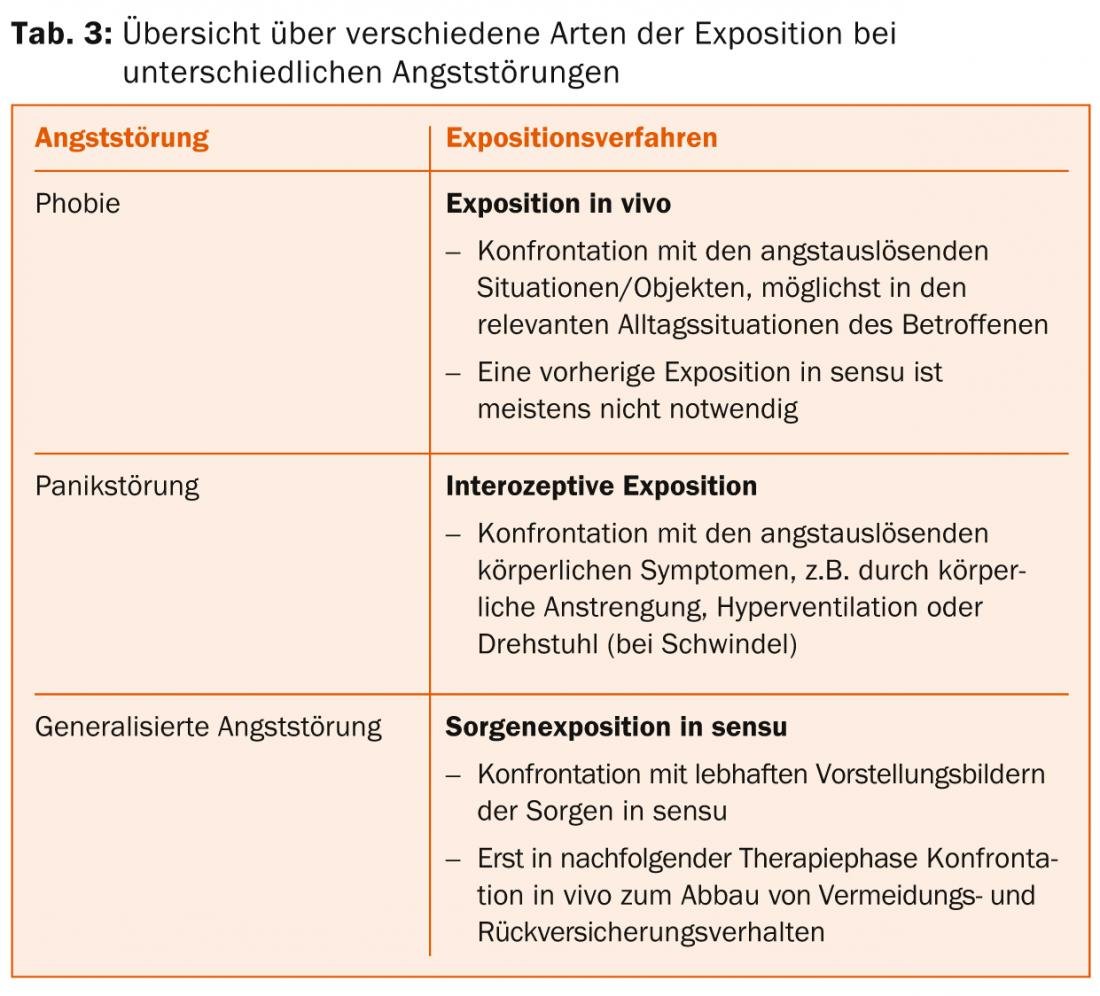

If self-help instructions are unsuccessful, or if a disorder is present that goes beyond mild anxiety symptoms, disorder-specific treatment with a designated professional should be initiated as soon as possible. The treatment of choice is psychotherapy, with by far the best evidence for cognitive behavioral therapy. This can take place individually or in groups; core elements are exposure with response management as well as cognitive procedures to change dysfunctional assumptions and – especially in social phobia – to build social skills. The different forms of exposure, which are applied depending on the anxiety disorder, are listed in Table 3 . In practice, a graduated approach with a gradual increase in the severity of the situation based on a previously created individual anxiety hierarchy has proven effective.

In the case of complex disturbance patterns, other cognitive-behavioral therapy methods and the incorporation of systemic and/or psychodynamic elements also play an important role. The choice of approach is individualized based on a careful analysis of the causative, precipitating, and maintaining conditions for anxiety symptomatology and, if necessary, depending on comorbidities.

Drug therapy for anxiety disorders should be considered when the patient is severely impaired and cognitive behavioral therapy alone has not produced the desired effect. In addition, the following factors, among others, play a role in practice, which may argue for drug therapy [7]:

- Severe anxiety symptomatology preventing specific psychotherapy (too little willingness to take risks; excessive demands to keep regular appointments)

- Presence of major comorbid depression

- Patient preference

- Contraindications to exposure therapy (e.g., due to cardiac insufficiency).

- Waiting time bridging until specific psychotherapy.

Antidepressants are primarily considered, and the best evidence is for many selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SSNRIs), and tricyclics [8]. Benzodiazepines should – among other things because of the risk of dependence – only be given for a short time in “anxiety emergencies” when reassuring medical talk is not enough. Another indication is occasionally for anxiety/anxiety initially triggered or exacerbated by antidepressants, which can be reduced by benzodiazepines.

Especially considering the long-term effects, drug treatment should always be combined with cognitive behavioral therapy to ensure therapeutic success even after gradual discontinuation of medication.

Prof. Dr. med. Michael Rufer

Literature:

- Weidt S, et al: My patient has anxiety – what next? Praxis 2012; 101: 523-530.

- Brühl AB, et al: Neural correlates of altered general emotion processing in social anxiety disorder. Brain Res 2011; 1378: 72-83.

- Etkin A, et al: Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. Am J Psychiatry 2007; 164: 1476-1488.

- Quide Y, et al: Differences between effects of psychological versus pharmacological treatments on functional and morphological brain alterations in anxiety disorders and major depressive disorder: a systematic review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2012; 36: 626-644.

- Aceto L, et al: Anxiety and panic disorders. Praxis 2009; 98: 59-65.

- Rufer M, et al: Stronger than fear. A guidebook for people with anxiety and panic disorders. Bern: Huber; 2010.

- Rufer M, et al: Combining psycho- and pharmacotherapy for anxiety disorders: Are there additive effects? State of research and practice recommendations. Swiss Journal of Psychiatry & Neurology 2006; 3: 30-34.

- Keck ME, et al: The treatment of anxiety disorders. Part 1: panic disorder, agoraphobia, generalized anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobias. Swiss Medical Forum 2011; 11: 558-566.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2014; 12(5): 21-24.