Pneumonia diagnosis and triage is anything but trivial, especially in the context of the current covid pandemic. As a basis for deciding which patients can be managed in the outpatient setting, the inclusion of the CRB-65 score and the ATS criteria is helpful, in addition to oxygenation. While classic pneumonia can be treated with targeted antibiotic therapy, several monoclonal antibody therapies are now available for covid patients, although there are several things to keep in mind.

The incidence of community-acquired pneumonia increases with each decade of life. The pathogens are mostly bacteria. Streptococcus pneumoniae is the most common pathogen, followed by Mycoplasma pneumoniae and viruses [1]. According to the pneumonia triad, the affected patients are immunocompetent individuals. In those over 65 years of age, pneumonia is associated with increased lethality [2]. “Pneumonia diagnosis is difficult,” admits Stephan Wieser, MD, Bethanien Lung Clinic, Zurich [3]. “There is no gold standard – nothing replaces you as a clinician,” the pulmonologist continued. Criteria are an acute course (≤21 days) with cough, plus ≥ 1 additional symptom/findings (new finding on clinical chest examination, fever >4 days, dyspnea/tachypnea) [3,5]. Older patients in particular often present oligosymptomatic. In addition to respiratory symptoms such as cough with or without sputum, dyspnea, and respiratory-related thoracic pain, general symptoms such as fever or hypothermia, and a general feeling of illness are common. Flu-like symptoms (e.g., myalgias, arthralgias, diarrhea) or neurologic symptoms (e.g., disorientation) are also possible [1]. If pneumonia is clinically suspected, thoracic imaging is recommended to confirm the diagnosis [1]. The inflammation of the lung tissue can be objectified as an infiltrate from a radiological point of view. Chest X-ray is also informative for differential diagnosis and for detection of complications or concomitant diseases, such as heart failure [1,3].

Which patients can be treated as outpatients and which belong on the IPS?

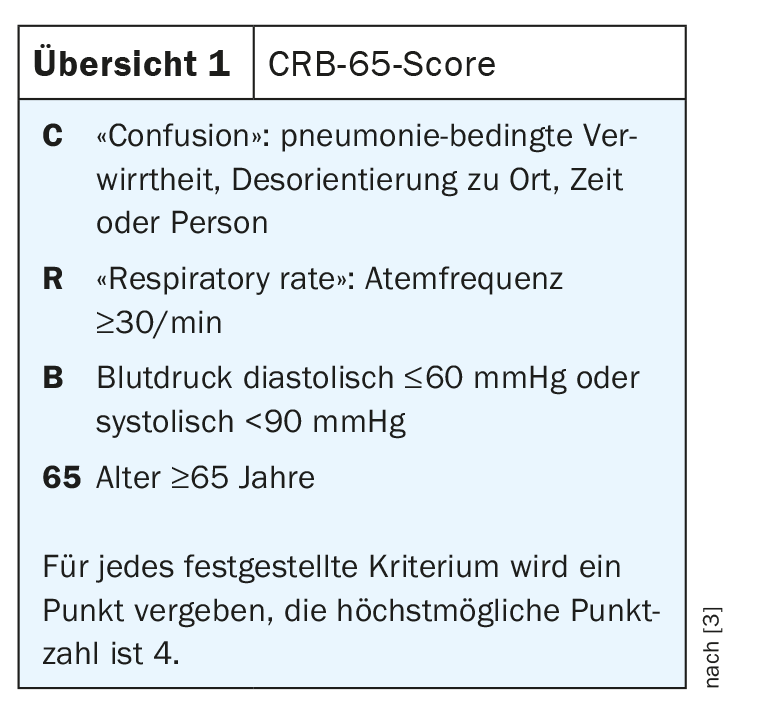

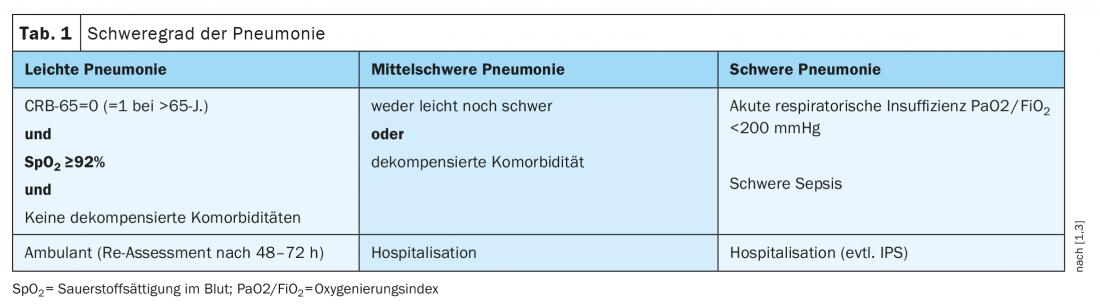

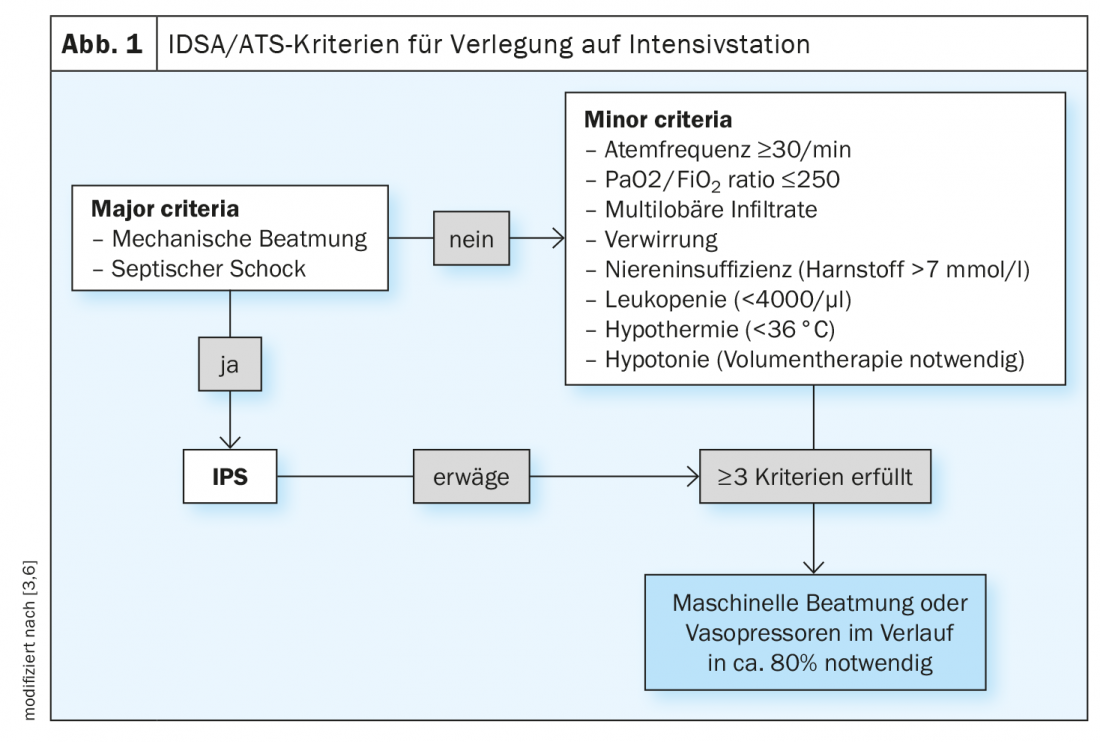

The CRB-65 index can be used with oxygen saturation for triage. “The CRB-65 score is clinically very easy to use,” said Dr. Wieser [3]. It is a clinical score that can be used to estimate the severity of community-acquired pneumonia and 30-day mortality (review 1) [3]. In addition, oxygen saturation is another relevant parameter. Patients who have a score of 0 on the CRB-65 or 1 in those over 65 years of age, have adequate oxygenation with SaO2 >92%, and appear stable by clinical assessment can usually be treated as outpatients (Table 1) [1]. However, if outpatient treatment is chosen, the patient should be re-evaluated after 48-72 h [1]. With a CRB score of 1-2, inpatient admission is recommended. Hospitalization should also be considered if acute respiratory failure or sepsis is present or if there is a decompensated comorbidity, Dr. Wieser said. A CRB score of 3-4 points indicates a significant risk of mortality and intensive therapy is indicated [4]. He added that whether ICU admission is indicated can also be assessed using the ATS criteria. If mechanical ventilation is required or septic shock is present, or if ≥3 of the minor criteria are met, an IPS admission should be made (Fig. 1) [3,6].

Targeted antibiotic therapy: what does that mean in concrete terms?

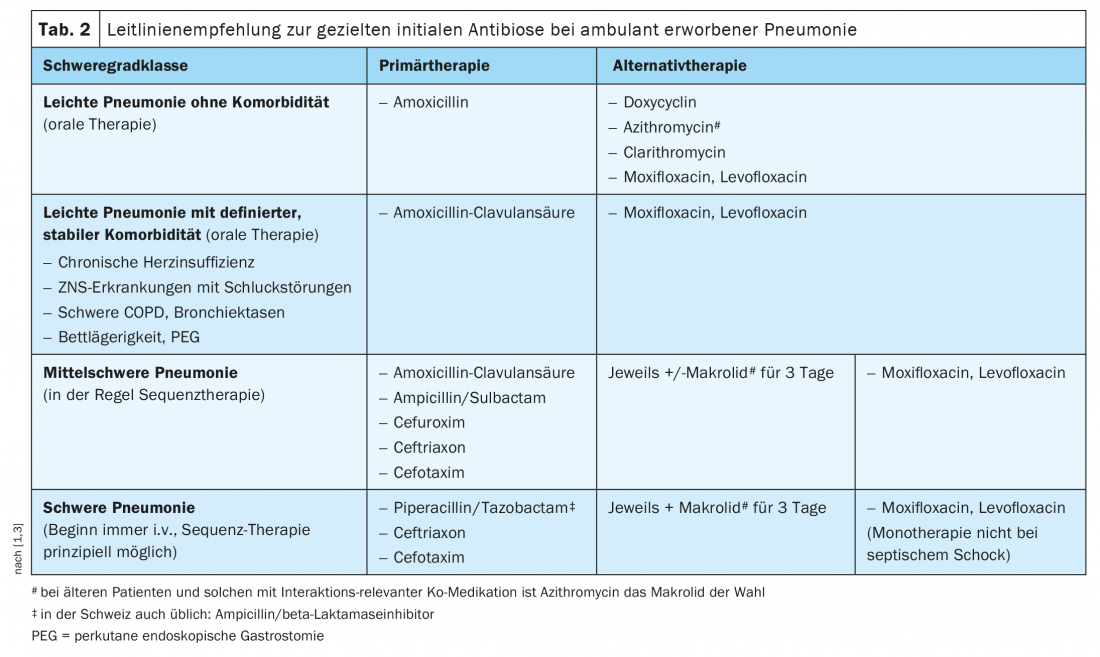

One of the goals of pneumonia diagnostics is to initiate targeted antibiotic therapy. Amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid works very well against pneumococci. Haemophilus produces slightly more beta-lactamase. In the case of risk factors such as nursing home, chronic diseases or aspirations, beta-lactamase formers are often present, so that one additionally treats with clavulanate, explains Dr. Wieser. Doxycycline, a tetracycline, is also very effective against pneumococci, although not to the same extent as amoxicillin. Doxycycline has particularly good efficacy against atypical pathogens. The same applies to macrolides, which also continue to have very good efficacy against pneumococci in Switzerland. In contrast, respiratory fluoroquinolones such as levofloxacin or moxifloxacin should be used in the outpatient setting only as a backup. These considerations are also reflected in the recommendations of the current S3 guidelines on empirical antibiotic therapy, although in this regard it is important to be guided by the local resistance situation and to adopt local recommendations, because this can vary a bit depending on the region, Dr. Wieser points out. However, the indication guidelines of the DGP provide a good orientation (Tab. 2) . Regarding influenza pneumonia, it is worth mentioning that the drug oseltamivir is given a higher priority in the current guidelines compared to the past, said the speaker.

Covid-19: “Happy hypoxia” – Measure oxygen saturation and respiratory rate!

“For covid 19 pneumonia, you may do the same triage,” the speaker summarized. However, the value of oxygen saturation is much greater, because there is the clinical finding of “silent hypoxia”, which is also called “happy hypoxia” [7]. “Patients don’t notice their hypoxia to the same extent, with dyspnea, as we’re used to in the past.”

There are various hypotheses as to why this “happy hypoxia” occurs, for example, that initially the expansibility of the lungs is preserved and the work of breathing is not significantly increased. Or that vasoregulation of the lungs is altered by microthrombi and vascular pathology, among other factors, and that loss of hypoxic pulmonary vasoconstriction occurs, resulting in more perfusion than ventilation, and thus the patient does not even really notice the hypoxia. Another hypothesis is that respiratory alkalosis occurs due to hypoventilation, resulting in more oxygen being bound to heme and a correspondingly longer period of still-maintained saturation before exhaustion occurs. Another hypothesis is that the SARS-CoV-2 virus acts directly neurally and negatively affects the mechanoreceptors and chemoreceptors in their afferents, and therefore the perception of hypoxia and respiratory mechanics is not immediately detectable by the patient. The bottom line is that if Covid-19 is suspected, it is especially important to measure respiratory rate in addition to oxygen saturation.

Monoclonal antibody therapy against covid-19: early use recommended.

Regarding treatment options for covid patients, studies on off-label use of inhaled steroids are controversial. However, with antibody drugs such as Ronapreve® (casirivimab / imdevimab), Xevudy® (sotrovimab) and Lagrevio® (molnupiravir), there are several therapeutic options that have been approved or successfully tested in clinical trials. Patients treated with casirivimab/imdevimab 1200 mg (i.v., 1×) (n=736) showed a risk reduction of 70.4% (95% CI; 31.6-87.1; p=0.002) in the endpoint of hospitalization or death at 29 days (1% vs. 3.2%) compared to the control group (n=748) [8]. Patients treated with sotrovimab 500 mg (i.v., 1×) showed a risk reduction of approximately 85% (1% vs. 7.2%) in the same endpoint [9]. Importantly, treatment with these monoclonal antibodies occurs early in the course of covid disease, which is also true for molnupiravir, as shown by phase III data published in the New England Journal of Medicine [10].

In Switzerland, the criteria for antibody therapy use are summarized in the “Recommendations for the Use of Monoclonal Antibody Therapies by the Swiss Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Care Group of the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force.” Currently, the indication is limited to over 12-year-olds with mild covid symptoms who do not require supplemental oxygen therapy, are unvaccinated, or whose vaccination/booster was ≥ 4 months ago (preferably with negative serology). In addition, patients are eligible for this treatment option if they are at high risk for a severe course, are unvaccinated or recovered, or if the covid sufferers are immunosuppressed, or are unvaccinated pregnant women or persons over 80 years of age [11].

Congress: Forum for Continuing Medical Education

Literature:

- S3 guideline on the treatment of adult patients with community-acquired pneumonia – Update 2021, www.awmf.org (last accessed Jan. 26, 2022).

- Ewig S, et al: Thorax 2009; 64: 1062-1106.

- Wieser S: Community-acquired pneumonia, Stephan Wieser, MD, FomF Jan. 25, 2022.

- Bauer TT, et al: J Intern Med 2006; 260(1): 93-101.

- ERS/ESCMID Guidelines for the management of adult lower respiratory tract infections. Clin Microbiol Infect 2011

- Chalmers JD, et al: Clin Infect Dis 2011; 53(6): 503-511.

- Machado-Curbelo C: MEDICC Rev 2020; 22(4): 85-86.

- Weinreich DM; Trial Investigators: N Engl J Med 2021; 385(23): e81.

- Gupta A, et al: COMET-ICE Investigators: N Engl J Med 2021; 385(21): 1941-1950.

- Jayk Bernal A, et al: N Engl J Med. 2021 Dec 16: NEJMoa2116044.

- FOPH: Recommendations for the use of the monoclonal antibody therapies sotrovimab and casirivimab/imdevimab from the Swiss Society for Infectious Diseases (SSI) and the Clinical Care Group (CCG) of the Swiss National COVID-19 Science Task Force, 6th January 2022.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2022; 17(2): 28-30