A physician’s transcultural understanding of his/her patients from other cultures can help him/her understand, among other things, problems of transcultural marriages, prejudice and its management, illness, and symptoms originating in a different cultural setting. In this context, political problems arising from the transcultural situation can also be better understood.

Conflicts in the doctor-patient relationship under the transcultural understanding

The wisdom that without relationship there is no education can be applied to the doctor-patient relationship; without relationship with the patient there is no understanding and healing. This working hypothesis is especially true for Oriental patients who borrow their self-concept from a collective culture (we-strength). This contrasts with Central European culture, which favors other personality traits with its individual culture (ego strength).

A physician’s transcultural understanding of his/her patients from other cultures can help him/her understand, among other things, problems of transcultural marriages, prejudice and its management, illness, and symptoms originating in a different cultural setting. In this context, political problems arising from the transcultural situation can also be better understood [3].

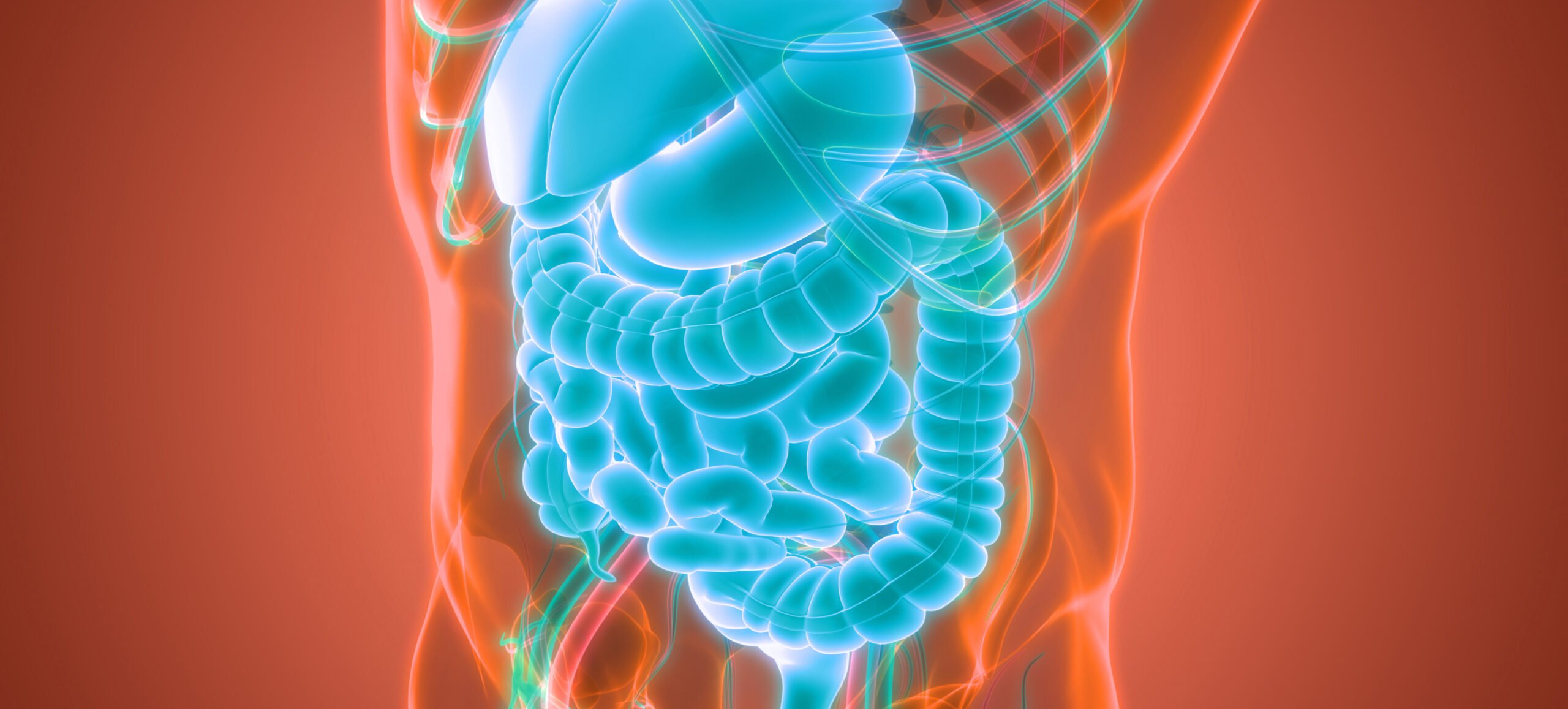

For the doctor-patient relationship this means that the doctor expresses his understanding of the individual life situation of the patient with his connection (relationship), who willingly opens up to the doctor through understanding and transfers to him the role of authority and the role of the knower (expectation of being helped and healed). If the physician can form the relationship with his patient from the oriental cultural area positively, he learns among other things also much about the different emotional stress processing, which are naturally derived in dependence of the cultural-social relations, which finally gives the physician information about the different choice of the organ. Cultural syndromes: often culturally different organs are mentioned to the doctor as the site of the disorder because of external factors, e.g. burning liver in Turkey, Iran and France in loss, separation and grief [4,5]. Likewise, the broken heart, similar to angina due to loss of love and loneliness hurts the heart of the Swiss or Germans, which is why the Germans are 4-6 times more likely to be treated with cardiac tablets compared to the British and Americans [4]. Other organs such as the abdomen, navel, and the head are also “organ-coded” as body-related signals and used for suffering.

The basis for this is a psychosomatic understanding that uses transcultural knowledge of how emotional stress experiences, culture-dependent concepts affect the body and provides information about the individual emotional experience of conflict. Since individual concepts of reality are closely linked to socialization norms and contexts of meaning, the individual emotional experience of conflict is situated in a close cultural and social context.

If this understanding succeeds (also in the form of understanding interpretations and questions), the previously self-evident standards with which facts and behaviors were judged (as a rule, this happens unconsciously) become permeable, so that a conscious distancing from one’s own concepts and behavioral habits can take place. With an understanding verbalization of the underlying unconscious needs (awareness), self-help possibilities are opened to the patient, in which he/she can first recognize these connections, how he/she can harmonize his/her needs together with his/her physician [3].

The previously taken-for-granted standards with which facts and behaviors were judged become permeable, so that a distancing from these concepts and behavioral habits can take place. Peseschkian refers to this process as “metatheoretical reinterpretation.” Transcultural understanding can increase the patient’s willingness to consider alternative solutions by making him aware of the relativity of the concept of illness and its dependence on the associated cultural frame of reference [6,7].

Example loneliness

“Loneliness has a positive connotation in German usage.” According to Wilhelm Tell’s motto “The strong man is most powerful alone,” the ability to be self-reliant, independent and alone is considered by many to be the epitome of strength. In Germany, it is not very noticeable when someone goes for a walk alone and thinks about something. In the Orient, such behavior usually arouses suspicion: “Is he offended? Is he depressed or even melancholic? Surely he can’t do it to himself or to us by shutting himself out. If he has sorrow, surely we can help him!” The attempt to experience loneliness and to withdraw from current social events is understood as a disturbance of mutual trust [6].

The example of the transcultural meaning of loneliness shows how behaviors and their meanings, which until then stood outside of culturally shaped subjective ideas and concepts of reality, form the self-evident standard for the assessment of one’s own and others’ identities.

It should be noted, however, that transcultural thinking also takes place within a culture, because each culture, in turn, is also not uniform and homogeneous. Within the Federal Republic, there are regional cultural identities (which can be thought of for any other country as well) that can have more significant differences among themselves than with other nations. Also, for example, the problem of “woman”-“man” (even if both come from the same culture) would have to be put into perspective with transcultural thinking, since the role as “woman”/”man” is shaped socially, culturally and biographically.

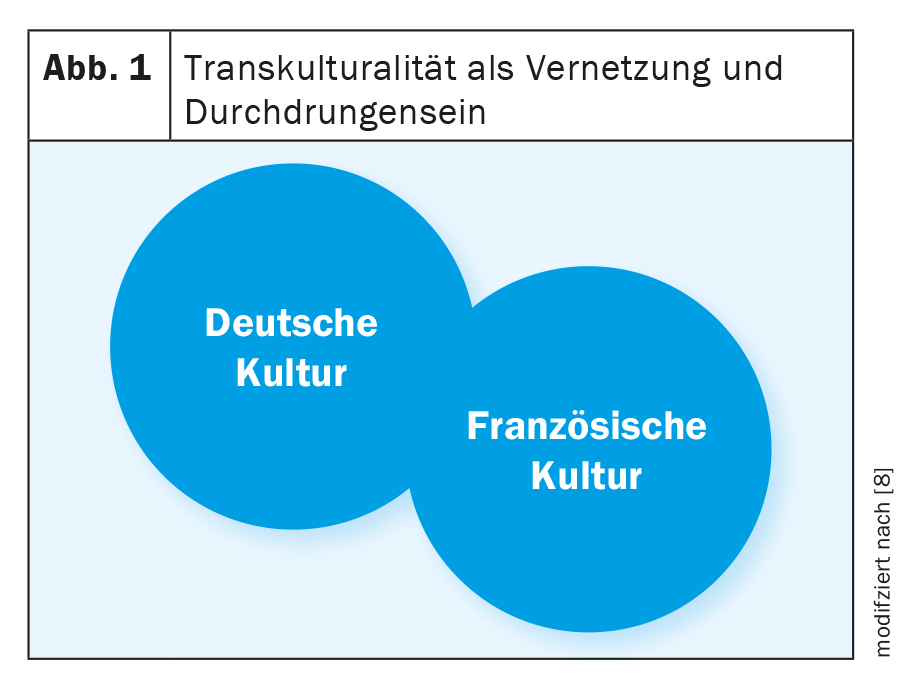

With the understanding of transcultural references, the conception of a reality, of a behavior, of a conception of values and norms, which until then had been regarded as the only and only legitimate one, becomes permeable, can gain elasticity, and enables a distancing from one’s own concepts and habits of behavior [8] (Fig. 1).

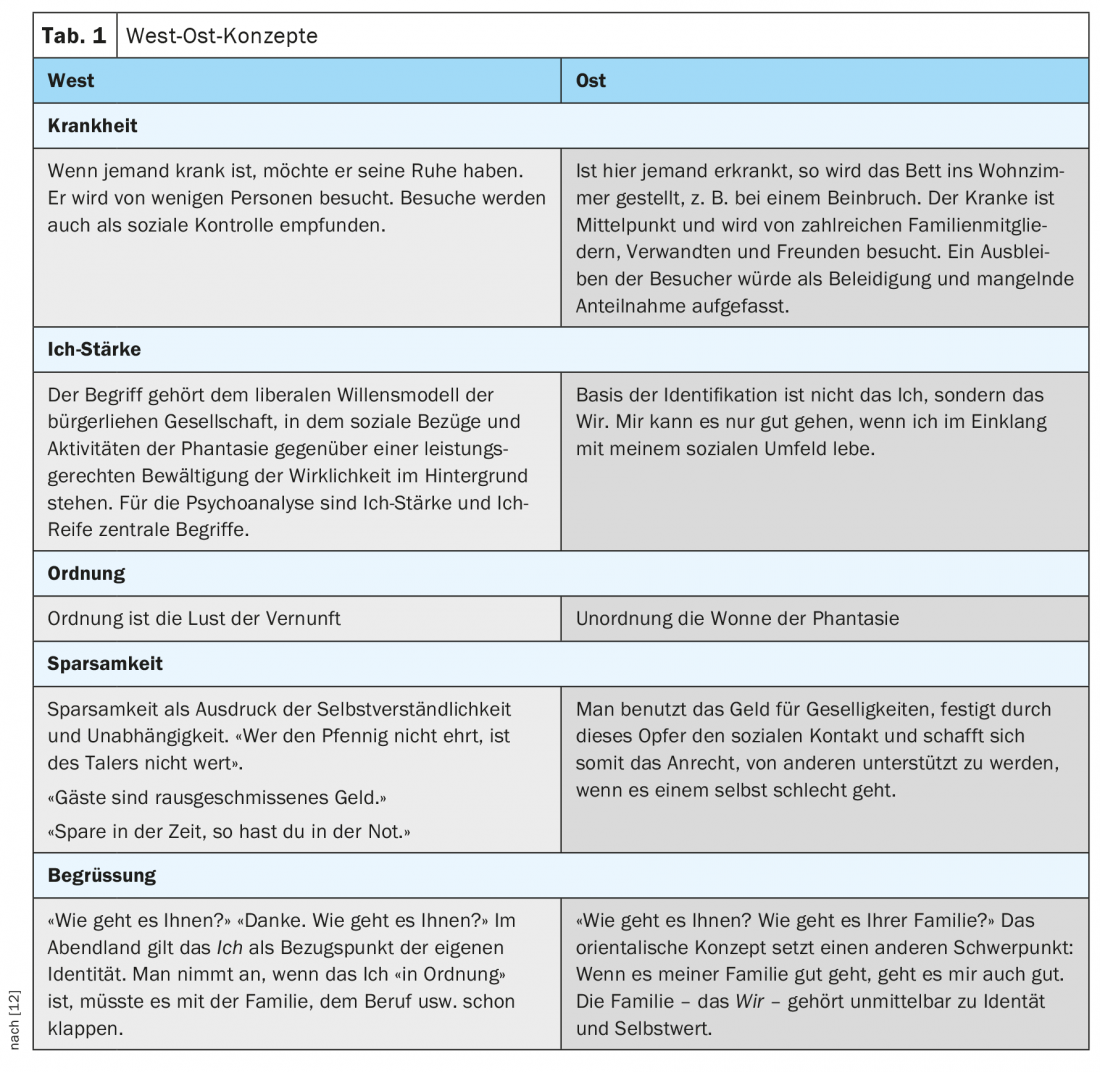

In the following, I would like to give a few examples of what is meant by this in everyday practice and what is meant to be clarified by the comparison of East and West concepts. These examples are to be understood as cultural typifications and are thus to be used for understanding.

The Balance Model [3] – Life Focus in East and West

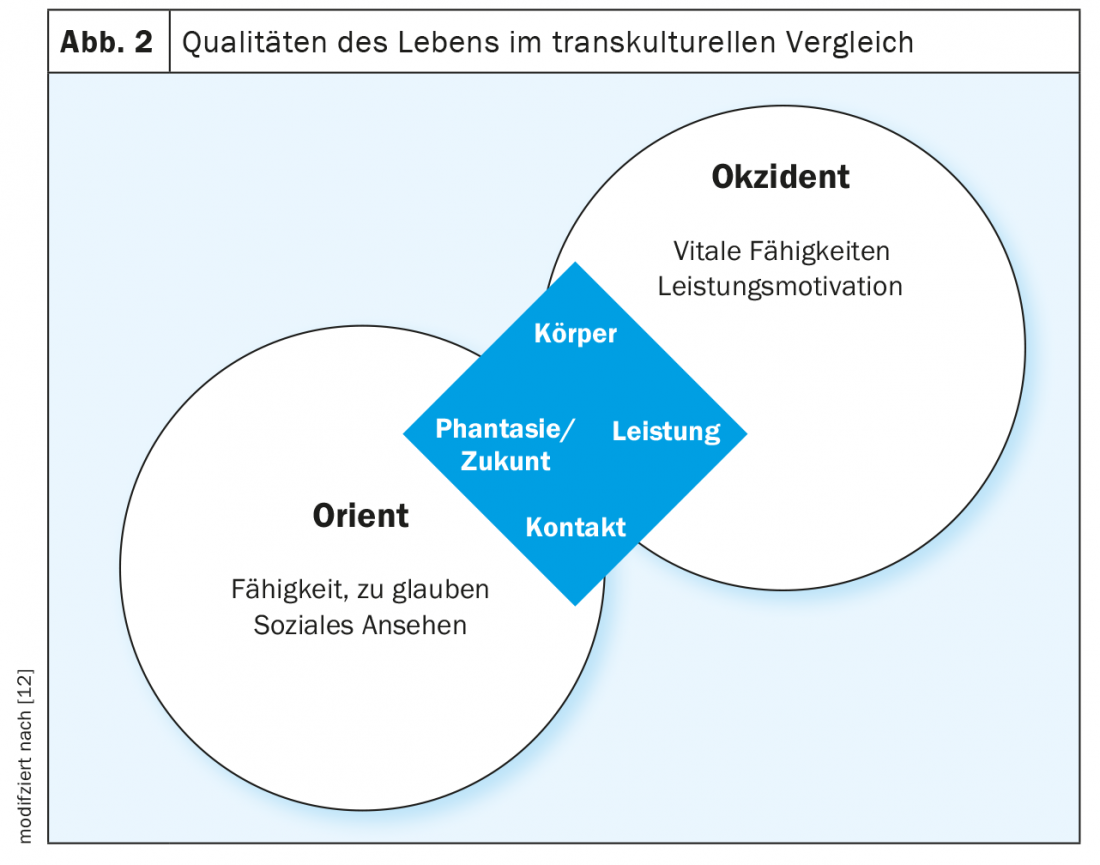

Implicit in the balance model is a notion of comprehensive health. If the four areas are occupied and lived in a relative balance in daily life, if a balance is possible within these references, then we can speak of quality of life in the sense of health as a whole. This refers to the following points:

Body: health, sexuality, aesthetics, hygiene, sleep-wake rhythm, sport/exercise, nutrition and pain; possible symptoms: psychopathological, psychomotor, vegetative symptoms and anxiety about the body;

Performance: productive area of the person, especially the profession; possible symptoms: stress reactions, self-esteem problems, fear of failure, discharge depression, etc…;

Contact: Society, family, friends, acquaintances, other cultures; possible symptoms: Inhibition, social anxiety, object anxiety, obsessive-compulsive behavior, detachment problems, etc…;

Fantasy/future: religion, meaning, worldview, view of man, philosophy; possible symp-to-me: obsessive thinking, anxiety psychosis, helplessness, resignation, suicidality, etc.

If the balance model is a symbol of wholeness, then health is an ideal state in which the distribution of energy in all areas is continuously balanced.

With the balance model according to Peseschkian [9] (Fig. 2) cultural differences can be shown, how in the different cultures the main points are emphasized differently and about this also a different concept of health and illness (symptoms) can be deduced. In the so-called “Western” cultures, the emphasis is favored on the areas of body and performance (appropriate descriptions for this: ego-strength and performance society), while in the “Eastern” cultures, the emphasis is on the areas of contact and imagination/future (appropriate descriptions for this: collective society and we-strength).

If it has already been written here that personality is composed of cultural habits (concepts, norms, and worldview), then it is accordingly to be expected that conflicts, disorders, and illness correlate to this.

Case study

The transcultural problem can be illustrated by an example with a 64-year-old Iranian man who came to my practice for an initial interview in October 2020. When asked what would bring him to me, he cited marital problems. The marital problems would have arisen more and more in recent years, as his wife had taken up a job with a travel company for about 10 years and had built up increasingly close relationships with colleagues there, which would lead to the wife being out of the house more and more. He also complained of sleep disturbances, stomach and intestinal problems, inner restlessness and also feelings of anger towards his wife.

The patient has been married to a woman sixteen years younger for 18 years. Both have two children (daughter 14 yrs; son 12 yrs). The patient is Muslim and employed in the IT field. His wife is from East Germany, is Protestant, but religion would not play a role for his wife. The following excerpt from the initial interview will briefly illustrate the problem:

Pat: “It makes me aggressive, she’s often with these women from her work after work and I don’t get to see how she’s doing and what she’s doing there.”

Therapist: “You’re upset that your wife has developed her own circle of friends with co-workers and your wife doesn’t inform you about it?”

Pat.: “That’s not possible. Why is she involved with strangers when she has a family?”

The patient is visibly excited and looks very serious.

Therapist: “You wish your wife would see family and marriage as her center of life?”

Pat.: “Yes. What’s the point?”

Therapist: “Well, I think your wife has a desire to have her own circle of friends in addition to her family.”

Pat.: “I don’t do that. I always came straight home after my work.”

Therapist: “You wish your wife would be with you and your children much more?”

Pat.: “Yes. She should be much more responsive to me, approach me more and understand my feelings. If she would only show half of her feelings and sensations, I would be happy. When I approach her about it, she only answers that she is a social being and avoids me.”

The conflict situation of the pat. becomes understandable against the following background. The patient had met his wife at work in the early days of his career. They quickly became close and got married. However, he had to experience how his wife’s parents had a negative attitude towards him because of his foreign origin. The way in which they openly and clearly indicated this had offended the patient very much, but due to his oriental politeness he did not let it show. On the contrary, he had always encouraged his wife to continue contact with them, which the in-laws had broken off after the marriage. It was incomprehensible to the patient how parents could behave so dismissively towards their daughter and grandchildren.

In the therapy it could be made clear to the patient that he had taken over for his wife on the one hand husband and on the other hand unconsciously also the father role. The Iranian patient, although a Muslim but not a practicing one (as he pointed out), had unconsciously adopted the religious-cultural imprints unreflectively and unthinkingly expected his wife to fulfill his expectations, virtually as her self-evident duty. By this he meant that it was natural for him that his wife would follow him and support him fully in everything, which is how it worked in the first years of marriage (in the sense of the patriachal role of the husband). In the course of the further years of marriage, the wife began towards her husband (in the sense of collusion according to Jörg Willi* [10]) to further liberate herself, which can be understood as a detachment from her unconscious father, as an expression of her post-maturing autonomy, i.e., if she directed her defenses against her husband, this liberation was unconsciously actually directed at her father. In other words, her increasing desire for autonomy from her husband (the patient) was unconsciously for detachment from her inner father.

* In his model of couple collusion, Jörg Willi outlines that at the beginning of a relationship the different images of self and others are unconsciously the main motive to find each other as a couple, which after a few years becomes the object of conflict. E.g. The woman is looking for a strong man to lean on, the man is looking for a woman who can lean on him and he can take responsibility for her. This original motivation becomes the object of the accusation: The woman accuses the man of always wanting to dominate and determine her, and the man accuses the woman of always having to take care of everything and not being able to lean in sometimes.

The patient, in turn, unconsciously transferred his cultural expectations to his marriage and wife, from whom he expected fidelity and docility, which shaped not only his understanding of family but also his narcissistic concept of self-worth (self-love). He experienced his wife’s autonomy aspirations as a mortification of his narcissistic affirmation as a husband, as well as infidelity and being abandoned by his wife. All autonomous developments of his wife the patient took very personally, directed against him. Based on his concept of politeness, he tried to make his wife feel guilty through subtle accusations, along the lines of how she could do this to him. In the process, he increasingly directed his aggression against his own ego, which in turn led to the physical symptoms described. This, in turn, prompted the wife to emphasize autonomy even more in order to break away from her husband. Both spouses were entangled with each other on an unconscious level, with their unmastered and unreflective individual-cultural socialization norms, each of which was unconsciously transferred to the partner, leading to the misunderstandings described.

Only the processing of the transcultural background helped the patient to gradually understand his behavior in the context of culturally different expectations, to step out of the paternal role in order to strive for an understanding turned attitude towards his wife. In further sessions, the patient learned impulse control over his feelings of grievance. This helped the patient to distance himself from his own expectations towards his wife, to adopt more of a benevolent attitude in order to step out of the projected father role and to communicate in a more partnership-like manner, which visibly relieved the tense marital situation.

Conclusion

Transcultural thinking would practically be the possibility to look at solution ideas and alternative patterns from other cultures, to transfer them into the personal system and to try them out in one’s own context. In the doctor-patient relationship with patients from other cultures, it promotes an understanding of the culturally-individual symptom and illness history that the patient unconsciously presents to the doctor.

This explanatory approach, which contrasts and highlights multi-layered and ambiguous realities through transcultural relativization, offers the opportunity, especially in relation to the doctor-patient relationship, to offer physicians new explanatory concepts in strengthening and developing a high level of integration, which can provide access to alternative approaches to solutions in the doctor-patient relationship. Conflicts and disorders should also be scrutinized from a transcultural point of view in order to become more aware of potential biased thinking patterns, which in turn commit the physician to one-sided problem-solving strategies (cf. to this [11]) and do not allow for active conflict management (circular concepts, i.e. one remains in the usual cultural habits of thought, does not look beyond one’s “edge of the plate”). Also, this may possibly be partly responsible for diagnosing symptoms such as hopelessness, powerlessness, and burnout.

The transcultural understanding, taken further, could be postulated: People realize that the earth is only seen as one country and that all people are its citizens. In this sense, this thinking and understanding would be able to have a considerable influence on the development of all people of this earth and people would not only see the foreign in the other cultures. Instead, new opportunities, which would contribute to international understanding and casually be a peace mission.

Take-Home Messages

- Personality is composed of cultural habits, in it concepts norms, world views and ideas of the primary reference group (parents, family) are integrated, which have thus become a personal and collective habit that we take for granted.

- But it is actually only habits due to relative repetitions in the cultural, social and individual habitat that become a kind of strict law. Access to further, inner, deeper possibilities are dependent on this learning process through repetition that shapes us.

- The result of this learning process may be that the individual (person) limits themselves by assumptions of what they can and cannot do. This reduces the individual’s creativity and ability to perceive new and diverse ways of dealing with conflict.

- With the approach of Positive and Transcultural Psychotherapy (according to Peseschkian), the practicing physician is offered an understanding and a tool for finding at least three solutions when there is no way out.

Literature:

- Bahá’u’lláh A: Messages from Akka [Akka 1868] 1982. Hofheim.

- Peseschkian N: The Merchant and the Parrot. Frankfurt 1979.

- Peseschkian N: Psychosomatics and positive psychotherapy. Berlin 1991.

- Kizilhan J: Cross-cultural aspects of somatoform pain disorder. Psychotherapist 2009; 54 (4): 81-88.

- Gün AK: Intercultural therapeutic competence. Possibilities and limits of psychotherapeutic action. Kohlhammer 2017.

- Peseschkian N: Positive family therapy. Frankfurt 1982.

- Rösing I: Is burnout research burned out? Analysis and critique of international burnout research. Heidelberg 2003.

- Welsch W: Transculturality – Reality – History – Task. Vienna 2017.

- Peseschkian N: Positive psychotherapy. Frankfurt 1977.

- Willi J: The two-partner relationship: the unconscious interaction of partners as collusion. 5th ed. Hamburg 2012.

- Savicki V: Burnout Across Thirteen Cultures. Stress and Coping in Child and Youth Care Workers. Westport 2002.

- Peseschkian N: In search of meaning. Frankfurt.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(1): 6-10.