Maltreatment of the elderly with neuropsychiatric disorders is common, usually as a result of informal, family caregivers becoming overwhelmed. A vague suspicion can best be clarified with questions from the Elder Abuse Suspicion Index. The most important prevention is to provide sufficient relief for the main caregiver.

In general, elder abuse is common in Europe, as revealed by a representative survey of 4467 people aged 60-84 years living in private households from seven European cities: 22.6% reported at least one instance of abuse in the past year, 19.8% in the form of psychological, 3.9% in the form of financial, 2.6% of physical violence (0.7% with injury), and 0.8% of sexual violence [1].

Violence against the elderly is defined by the WHO as deliberate actions that burden, injure, harm or limit those affected, but also as conscious or unconscious failure to provide necessary support.

While elder abuse in elder care institutions is most often reported in the press, it is actually much more common and often worse in the home setting. The number of unreported cases there is enormously high, because home care is characterized by dependence and power, ambivalent feelings, unfamiliar roles into which relatives often slip without preparation, as well as the unraveling of previously repressed conflicts. This is all the more important as 80% of people over 80 in Switzerland live at home and 60% are cared for by relatives. This also affects the majority of elderly patients with neuropsychiatric disorders.

In a study conducted by the Zurich University of Applied Sciences, conflict patterns of domestic violence were investigated by means of qualitative analysis based on 31 complaint cases at the Independent Complaints Office for the Aged (UBA) [2]:

Intergenerational entanglement in addiction

Case study: A 94-year-old academic with mild dementia causes a kitchen fire in her single-family home, which she occupies alone. Her son places her in a private nursing home nearby. She reaches the UBA with the help of a friend and complains that her son hardly visits her, that she is no longer allowed to go to her house, although she urgently needs clothes from there. The son places his daughter, who is studying, in the house and wants to buy it for her below market price. She worries she will soon no longer be able to pay for the expensive home. Thanks to the mediation of UBA, she can return to her home and is cared for there with Spitex.

Elder abuse in the partnership with dementia

Case study: an 87-year-old pharmacist who is mildly cognitively impaired lives with his 85-year-old wife, who drinks a lot of white wine, then drunkenly hits him repeatedly with her walking stick. He repeatedly had her psychiatrically hospitalized for it per FU, but always took her home after two days. After clarifying the exact conflict and realizing that she has only been drinking excessively since her dementia, he agrees to the proposal to make the household alcohol-free. As a result, she forgets to ask for alcohol and no longer becomes aggressive.

Sibling conflict over caregiving services

Case study: A 90-year-old mother lives with dementia in an old house next to the new building of the eldest daughter. This she visits every evening. The second daughter organizes the care of her mother with private employees six days a week. She looks after the third daughter on Sundays. The first daughter keeps sabotaging the orders to the second daughter’s employees and insults the sisters. The second daughter goes to the complaints office, and the office is able to defuse the conflict with conflict mediation, which involves a clear division of tasks among the three sisters.

Social proximity and financial exploitation

Case study: A 75-year-old man with a speech impediment has been married to a 50-year-old Jamaican woman for four years and lives on AHV and supplementary benefits. They send almost all of their cleaning wages to their home country, but they do not declare the wages as income to the Office for Supplementary Benefits. This demands a large repayment, which he is unable to make. He is also afraid of her, who is physically superior to him. He wants a separation and eventual divorce, but feels helpless. Thanks to mediation by various UBA experts, acceptable solutions can be worked out (repayment in small installments, separate housing and divorce).

Neighborhood conflict due to neglect

Case study: An 80-year-old mother with dementia lives on the fourth floor of an apartment building, with her depressed daughter on the first. She helps as much as she can, but this is often rejected by the mother as undue interference. Instead, however, this often rings at neighbors at inopportune times because of trivialities. These reach the UBA, whose care expert brings about professional Spitex care and informs the neighbors and empowers them to also be allowed to separate themselves. The daughter is thus greatly relieved and her depression improves.

Autonomy of action despite the need for protection (stealing mania)

Case study: A 73-year-old silverware dealer lives in a retirement apartment. Their administration is done by the son. She accuses the latter of stealing from the silver. The police judge her to be untrustworthy and suspect a paranoid. Her memory is intact and she insists on bribing her son. She finds someone to help her move abroad to live with her sister. After a short time, she also feels stolen from there and wants to go back to Switzerland.

What to do in case of suspicion?

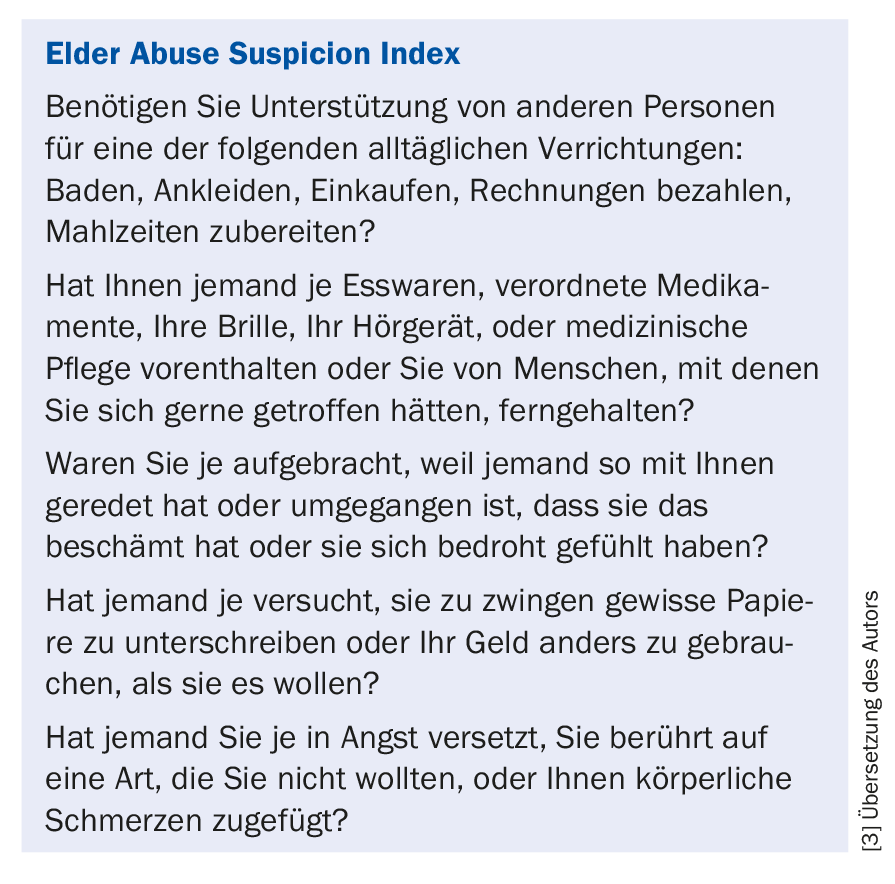

Since especially the long home care of chronically neuropsychiatrically ill elderly persons is a risk factor for elder abuse, it is necessary to always think about assaults of caregivers when providing medical care. Very helpful in case of a vague suspicion, an “uneasy gut feeling”, is a questioning based on the “Elder Abuse Suspicion Index” according to Jaffe (see box) [3].

Preventive counseling is important in the care of neuropsychiatric chronically ill patients, which promises to prevent excessive demands on family caregivers as much as possible. This includes informing the family at an early stage about the locally available professional services for home and day care, possibly involving experts from the relevant health leagues (e.g. MS League, Parkinson’s Association, Alzheimer’s Association). Often, a family meeting with all involved is also helpful for organizing and agreeing on all members of the formal (= professional, paid) and informal (= provided by relatives, unpaid) helpers’ network.

A key medical task here is to make family caregivers aware of the danger of being overwhelmed and the need for relief. Especially when a single person provides care alone, in the long run there is usually either illness of the person providing care (e.g., depression or other stress-related illnesses such as gastric bleeding) or mistreatment of the person being cared for. In the process, the elderly should be encouraged to accept relief from grandchildren; teenagers are also often able to do this and are well motivated to do so. Further training courses for family caregivers and regular participation in family groups organized by health leagues or Pro Senectute are also very helpful.

If a suspicion of elder abuse is confirmed, the help of the UBA can also be sought; in cases of hardship, the child and adult protection authority KESB must be called in. In acute and serious situations, hospitalization in a somatic or psychiatric clinic is often indicated, if necessary by means of a “Fürsorgerische Unterbringung”. It is important to inform the clinic about the suspected abuse so that a premature return to dangerous home care can be avoided. Since in cases of elder abuse the victim is usually dependent on continuous care, a police expulsion – as is otherwise the standard measure in cases of domestic violence – can usually not be applied and accordingly a report to the police is usually not indicated except in cases of acute life-threatening incidents.

Literature:

- Lindert J, et al: Violence against people over 60 years and depression and anxiety-Results from a European study. Health Care 2010; 72 (08/09): P69.

- Baumeister B, et al: Six conflict patterns: results of a file analysis. Pp.43-64. In: Baumeister B. and Beck T. (eds.): Schutz in der häuslichen Betreuung alter Menschen. 2017; Bern: Hogrefe Verlag

- Yaffe MJ, et al: Development and validation of a tool to improve physician identification of elder abuse: The Elder Abuse Suspicion Index (EASI). Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect 2008; 20 (3): 276-300.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(1): 32-34