Carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS) is the most common focal neuropathy, usually with no specific cause. The nightly falling asleep of the hand, especially of the fingers I-IV, combined with pain as well as the disappearance of the symp-tomatics after shaking the hand is practically pathognomic for a carpal tunnel syndrome. First and foremost, conservative measures such as wearing a volar wrist splint at night are the main focus. In case of increasing CTS symptoms, failure of conservative measures or persistent sensory disturbances and/or paresis of the abductor pollicis brevis muscle, surgical decompression is indicated. Preoperative neuro(myo)graphic evaluation is usually obligatory.

Patients with peripheral nervous system disorders are frequently referred for neurological evaluation. In my practice, these are predominantly focal neuropathies, such as cervical and lumbar radicular lesions, carpal tunnel syndrome (CTS), and ulnar nerve neuropathy. Somewhat less common are lesions of the axillary nerve, radial nerve, common peroneal nerve, and lateral cutaneous femoral nerve (meralgia paraesthetica) and peripheral facial paresis. In this article, I would like to limit myself to the most common focal neuropathy, carpal tunnel syndrome CTS, and give you a bit of an understanding of electromyographic testing. After all, this is a “core business” of the neurologist.

Symptoms and causes of carpal tunnel syndrome

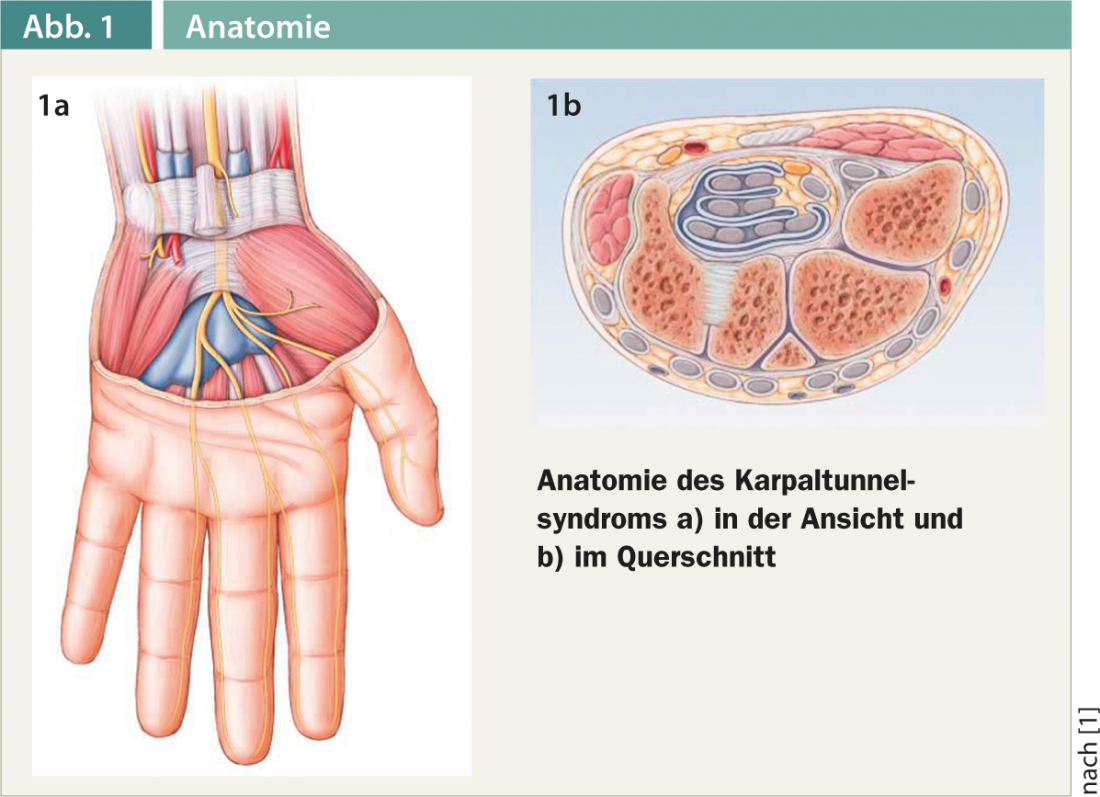

The most common nontraumatic peripheral nerve lesion is carpal tunnel syndrome. This is a chronic compression of the median nerve in the carpal tunnel as it passes under the retinaculum flexorum (Fig. 1a and b).

Carpal tunnel syndrome is the most common constriction syndrome and accounts for approximately 45% of all nontraumatic nerve injuries. The incidence is reported differently in the literature. The risk of disease is 8-10%, with women being about twice as likely to develop the disease as men. CTS occurs primarily between the ages of 40 and 50.

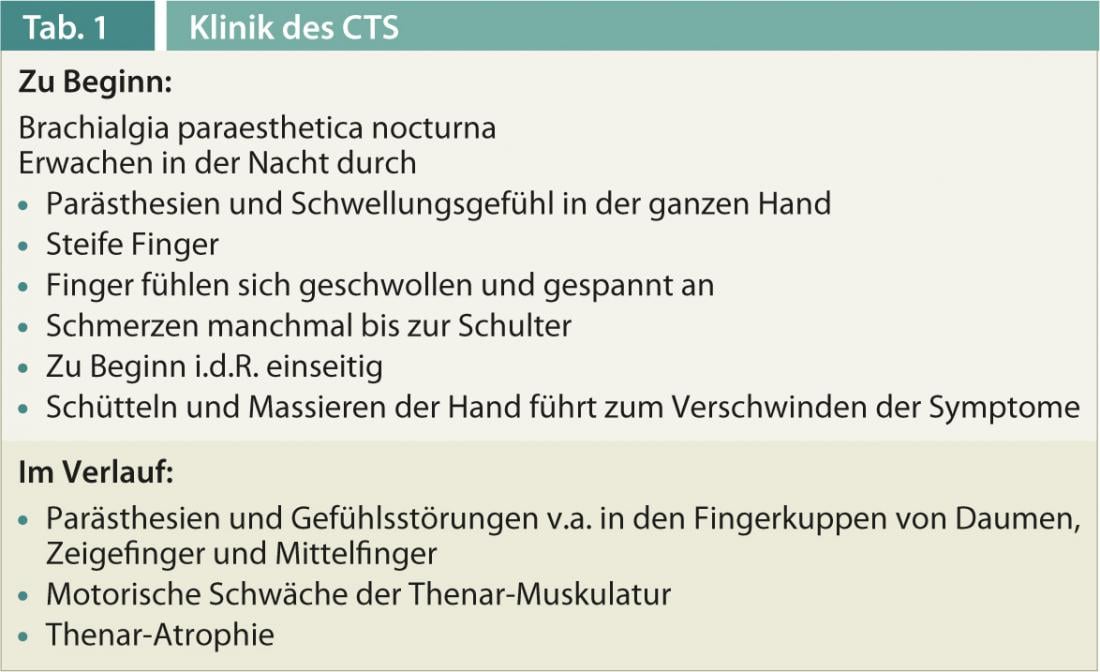

A typical symptom is “brachialgia paraesthetica nocturna”, which often occurs unilaterally at the beginning. Affected individuals wake up at night with paresthesias and swelling sensations throughout the hand. Stiff fingers, which feel swollen and tight, and pain that extends to the shoulder are often reported. Shaking and massaging the hand initially causes the symptoms to disappear. During the day, the same symptoms occur during certain activities such as knitting, driving a car, bicycle or motorcycle. A history of the above classic CTS complaints is virtually pathognomonic. Later, paresthesias and sensory disturbances persist, especially in the fingertips of the thumb, index, and middle fingers, and motor weakness of the thenar muscles and thenar atrophy occur (Table 1).

More difficult are situations (usually assigned by rheumatology) in which cervicobrachialgia is present as a result of arthritis, polyarthritis, or soft tissue rheumatism. Anamnestically, there is usually a pain syndrome involving the neck-shoulder-arm and hand on both sides.

Paresthesias usually extend beyond the hand and are also reported in the arms.

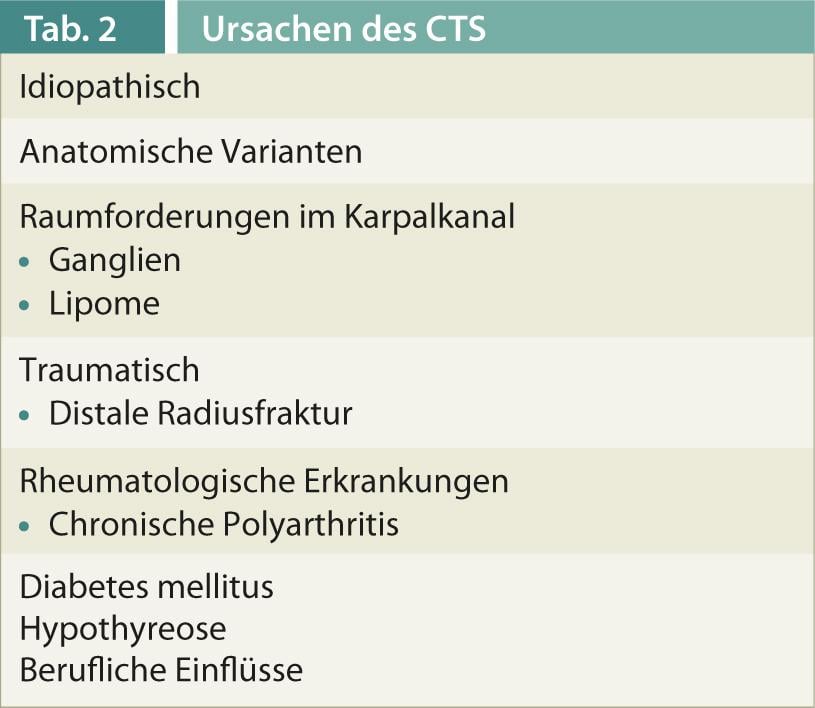

A variety of possible causes can be found in the literature. CTS may be the result of a distal radius fracture, a space-occupying lesion in the carpal tunnel (ganglia, lipomas), an anatomical variant, or may occur in the context of chronic polyarthritis, diabetes mellitus, or hypothyroidism (Table 2) . In most cases, however, no specific cause can be verified.

The typical CTS symptoms are known to most general practitioners and are first treated conservatively by wearing a volar wrist splint at night or by local steroid infiltration before the patient is referred to a neurologist for an EMG examination and surgery.

Neurological and neuromyographic examination

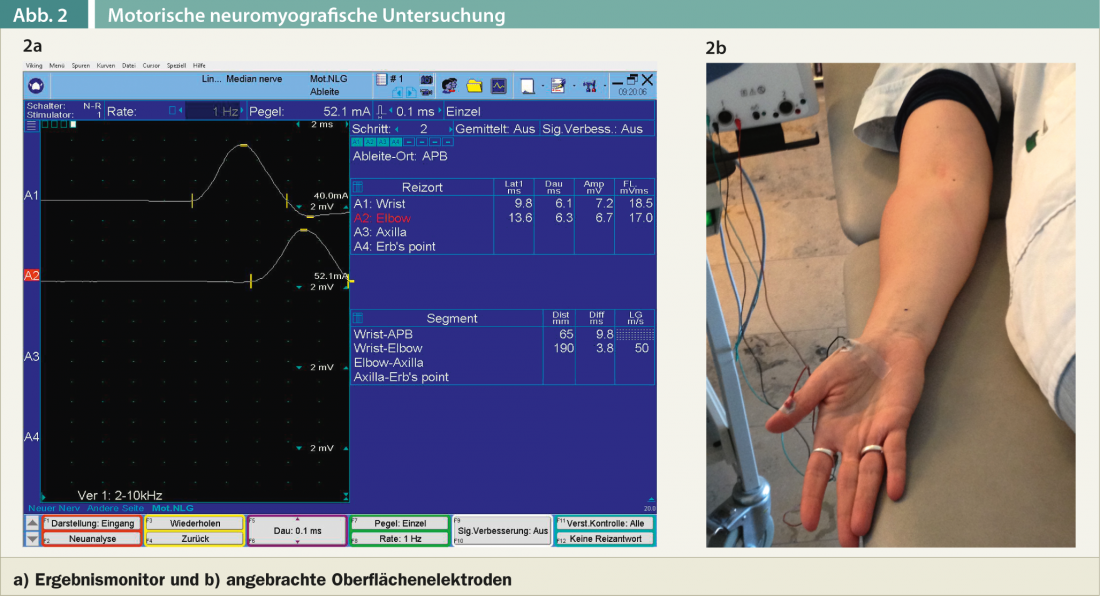

If the patient has a history of classic carpal tunnel syndrome symptoms and there is no concomitant disease such as diabetes mellitus or a rheumatological condition, I limit myself to the neurological examination of the cervical spine and upper extremities. The clinical and electromyographic examination serves not only to detect carpal tunnel syndrome, but also to exclude other causes, especially a cervical radicular lesion of the C6 and C7 nerve roots. After the clinical examination, a motor and sensory neurography of the median nerve and usually also of the ulnar nerve is always performed. Motor neurography of the median nerve involves a lead over the abductor pollicis brevis muscle. Irritation of the median nerve is performed slightly proximal to the carpal tunnel as well as in the region of the ulnar flexion (Fig. 2a).

The amplitude of the motor cumulative potential, the distal motor latency (time duration when the median nerve is stimulated slightly proximal to the carpal tunnel until the appearance of the motor cumulative potential over the abductor pollicis brevis muscle), and the motor conduction velocity are measured (Fig. 2b).

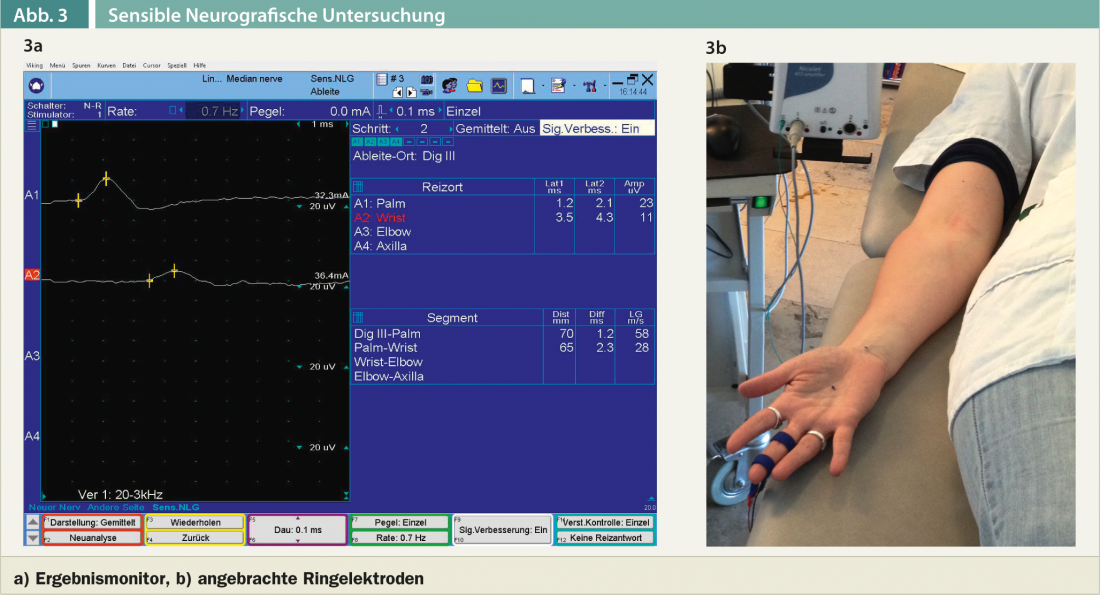

Sensory neurography can be performed in orthodromic or antidromic technique, although I routinely prefer the antidromic technique (Fig. 3a). The sensitive nerve action potential is recorded from one median finger, e.g., the middle or index finger or both fingers. (Fig. 3b). Irritation occurs in the vola and distal to the carpal tunnel. The very brief current stimulus is somewhat unpleasant for the patients examined, but is usually well tolerated. In cases of clinically evident thenar weakness or visible thenar atrophy and lack of motor cumulative potential over the abductor pollicis brevis muscle, a myographic examination of the abductor pollicis brevis muscle and the pronator quadratus or pronator teres muscles is also performed. This involves insertion of a needle electrode into the muscle. The myographic examination is uncomfortable for patients.The extent of the electromyographic workup depends on the clinical findings and is also likely to vary somewhat from examiner to examiner, depending on the school. There are currently no internationally recognized guidelines on the assessment of the severity of carpal tunnel syndrome (e.g., mild, moderate, severe, marked, etc.) – and consequently it is likely to vary somewhat depending on the examiner. Slightly slowed sensory conduction velocity in the carpal segment with otherwise unremarkable parameters is usually classified as neurographically mild CTS. If all motor neurographic parameters(markedly prolonged distal motor latency, small sum motor potential) and sensory neurographic parameters(markedly slowed sensory conduction velocity in the carpal segment, small amplitude sensory nerve potential) are pathologic and if myographic evidence of denervation signs can be detected in the abductor pollicis brevis, CTS is classified as severe or marked. The subjective suffering pressure does not always correlate with the electromyographic findings. Thus, there are always patients who are significantly impaired by paresthesias and pain, although neurographically only a mild CTS is present. Conversely, there are patients who report to the physician only with a clear thenar atrophy and sensory deficits in the volar-sided fingers I-III and the ulnar-sided ring finger.

Controversy exists regarding the time at which surgical decompression of the median nerve should be performed. According to a recent CTS review in pharma-kritik, there are no clear studies regarding surgical indications. From a pragmatic point of view, the answer to the question of surgery seems to me to be simpler: Personally, in the case of clear and progressive CTS symptoms and failure of conservative measures, I consider early surgical decompression to be advisable. Surgical decompression should be considered at the latest in the presence of persistent sensory deficit symptoms.

Literature:

- NEJM 2002; 346: 1807-1812.

- BMJ 2007; 335: 343-346.

- JAMA 2000; 283: 3110-3117.

- Carpal tunnel syndrome, guidelines of the DGN; Status: 14.11.2012; Published by the German Society for Neurology, Georg Thieme Verlag.

- pharma-critics 2007; 9: 33-36.

- Vogt W: Carpal tunnel syndrome – pathogenesis, diagnosis and cause, insurance medical aspects. Lucerne 1998.

- Switzerland Med Forum 2006; 6: 209-214.

- Switzerland Med Forum 2004; 34: 565-588.

- Switzerland Med Forum 2012; 12: 480-484.