Drug-related disorders in adolescents impose severe burdens on the patient and his or her family and pose the greatest threat to development. When manifest dependence is added, clinical and social problems accumulate, especially in at-risk populations. In practice, there has been a growing trend over the past decade that even adolescent patients with psychiatric comorbidity rarely abstain from drugs. Alcohol and cannabis use in particular have become daily companions in terms of self-medication. Comorbidities with depression, ADHD, psychotic disorders and trauma sequelae characterize the complex situations that require primary care pediatric early detection and specialist early intervention. Basic diagnostics include multiple symptom assessments as well as self, family, and drug histories. The least restrictive setting with adequate safety and effectiveness of treatment should generally be selected for therapy. Inpatient detoxification may be required. Involving the family, e.g. through Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT) is useful in any case. However, permissive social conditions on the one hand and the unwinnable “war on drugs” on the other pose additional social challenges.

The development of an addiction problem is ultimately a long-term individual biopsychosocial event that affects the individual. Nevertheless, some basic patterns can be identified that often accompany early risk and thus the need for early intervention, particularly in at-risk populations [1]. These are:

- Early onset (before the age of 12)

- Rapid dose and consumption increase

- Consumption increasingly or exclusively alone and not in peer groups

- Indiscriminate replacement of one substance by the other

- Complete change of peer group

- Persistent mental focus on substance use.

Differential epidemiology

Adolescence, as a vulnerable period, is when most first experiences with psychoactive substances occur. The age of initiation for nicotine – despite declining smoking rates since the late 1990s – is 13-14 years; with alcohol, three quarters of up to 17-year-olds have their first experience. The first use of illicit drugs begins somewhat later. By far the most common first illicit drug is cannabis, with, for example, 0.6% of 12- to 13-year-old Germans having already had relevant experience of use. The proportion of young people with experience of consumption rises to 13.5% by the age of 17. By age 25, 40.9% of all adolescents and young adults have had their first experience with cannabis, with an overall decline in cannabis use.

For each age group, the proportion of boys with experience of consumption is higher than that of girls (for comprehensive information on current epidemiological studies, see [2]).

Experiences with psychoactive substances are only repeated if they have positive medium-term connotations. The altered state of consciousness (intoxication) experienced by the consumer must be suitable for generating a specific motivation to repeat. Therefore, a clear distinction has to be made between the extremes of one-time trial use in the sense of lifetime prevalence and intensive continuous use in the sense of weekly or daily prevalence.

Developmental tasks and developmental psychopathology

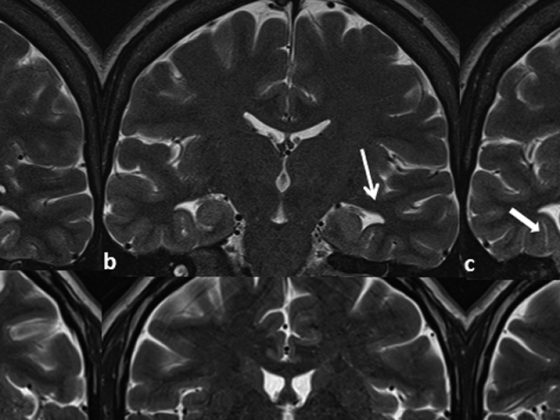

The developmental dynamic significance of coping with so-called developmental tasks is based, among other things, on the typical character of biographical transitions (table 1). Unmastered early developmental tasks reduce the likelihood of successful mastery of subsequent developmental tasks. Successive biographies with multiple stresses develop, in which the problems continue to escalate even without an increase in consumption [3]. From this chain reaction a principle of prevention and early intervention may be derived: Every temporal delay in the development of addiction means a relevant promotion of individual development [4]. This also and especially includes the adequate and timely treatment of adolescent psychiatric disorders and mental abnormalities in adolescence.

Clinical modeling

Psychological models focus primarily on learning, coping, conflict dynamics and motivation, and family-associated factors. Biologically oriented models focus on changes in brain and body organics (e.g., so-called addiction memory). Sociological models emphasize the macrosocial embeddedness of addiction. This includes the social definition of addiction or abuse, which may vary historically and regionally (overview in [5]).

The established transtheoretical model, which describes addiction development and cessation of consumption as a circular process (circulus vitiosus), but in which different interventions can be made at each point of the process, is still helpful for individual understanding [6].

Diagnostics and differential diagnosis

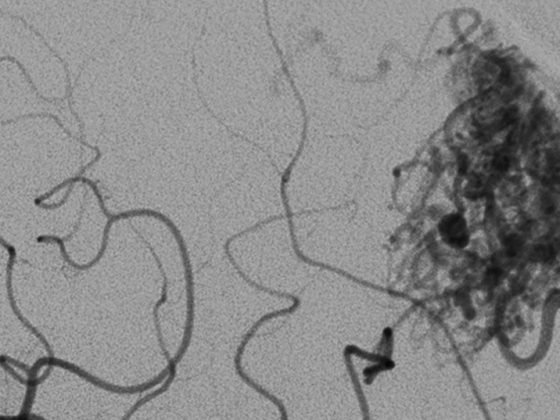

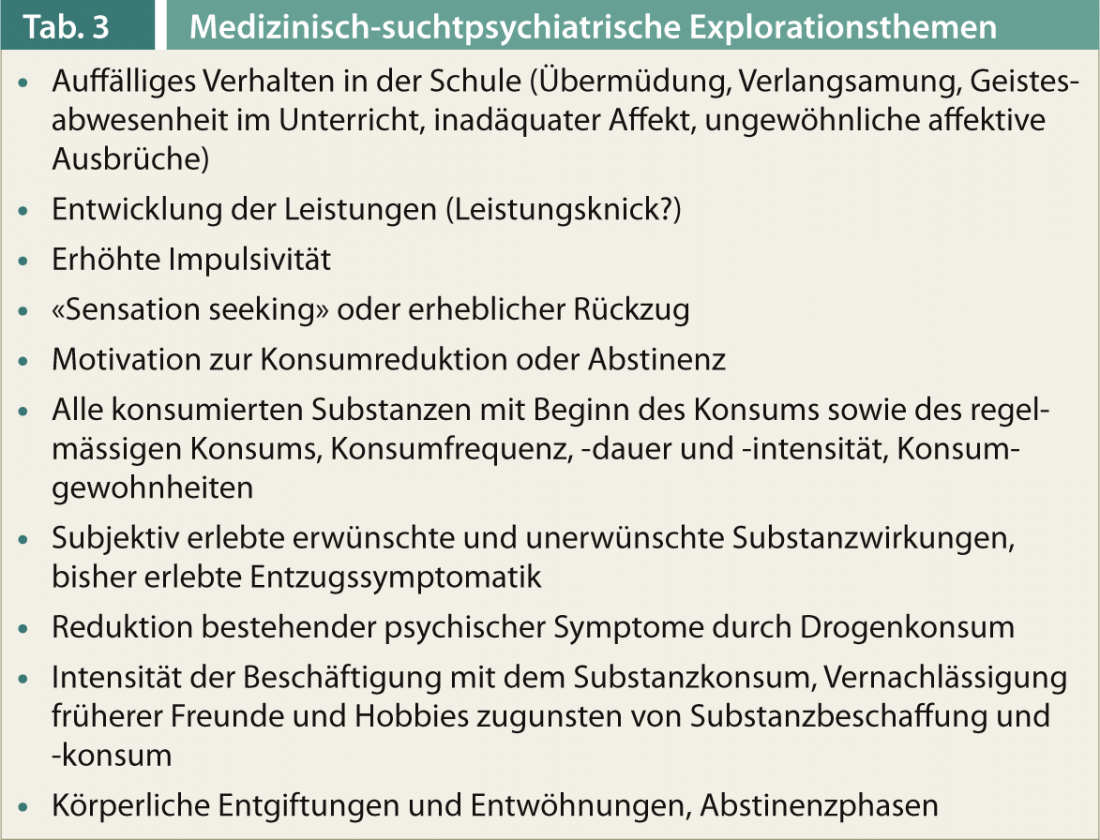

The multiple recording of the symptoms and the self-history, family history and an accurate drug history form the basis of any diagnosis. In addition, the psychosocial (tab. 2) and medical-biological consequences of drug use are systematically recorded and assessed at (tab. 3).

The face-to-face medical discussion should turn more to interactional, school, and performance-related problems – rather than focusing on the details of drug quantities, procurement, etc. High importance is to be attached to the representation of the adolescent himself at an early stage of consumption. The dissimulation and concealment tendencies typical of the serious drug addict are not yet pronounced in the case of harmful use, so that the adolescent’s statements about quantity, type of drugs and pattern of use are in principle credible.

Urine monitoring (unannounced if necessary) supplements these measures in many cases, but is used less for basic diagnostics than for checking compliance with (partial) abstinence and other therapy goals. Hair analysis is sometimes indicated for judicial purposes, but is of secondary importance for everyday practice. In any case, the anamnesis and laboratory diagnostics should be supplemented by a careful, complete physical examination (possibly by a specialist), since adolescents often conceal somatic symptoms, do not regularly visit their pediatrician or family doctor, and it is often only the addiction problem that reveals other physical abnormalities.

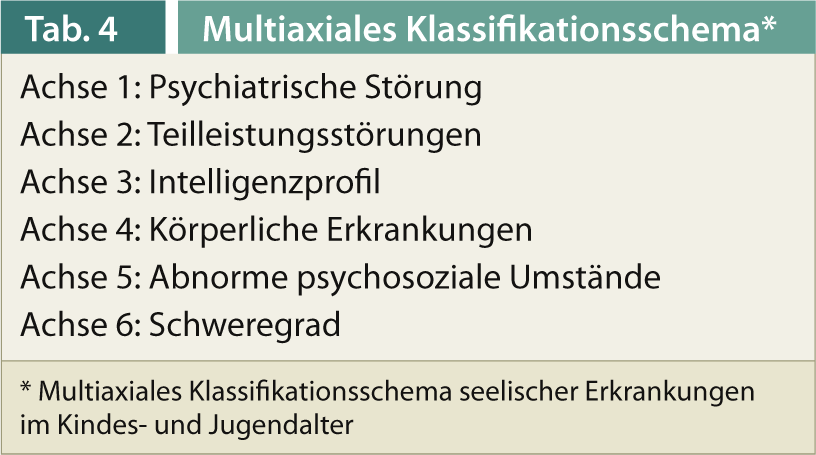

Through child and adolescent psychiatric multilevel diagnostics on the basis of the Multiaxial Classification Scheme for Mental Disorders in Childhood and Adolescence (MAS, Tab. 4), the topics of partial performance disorders and intelligence profile as well as family factors, which are important for development, are also to be mapped [7].

Therapy approaches

In principle, the least restrictive setting should be chosen in which adequate safety and effectiveness of treatment can be ensured [8, 9]. First of all, this concerns the physical safety of the adolescent himself (acute physical danger, intoxication-related danger to self) as well as third parties (danger to others from the adolescent).

If there is no need for an acute inpatient admission due to a somatic or psychiatric indication, the further selection of the intervention setting is decisive:

- Type and severity of substance dependence

- Type and quantity of substances consumed

- Risk of significant withdrawal symptoms

- Previous treatment failures in a less restrictive setting.

If necessary, detoxification should be provided as inpatient qualified withdrawal treatment, followed by rehabilitation in a specialized facility for adolescents with substance dependence.

Based on the previous school history, the current performance diagnostics, and any intellectual limitations resulting from the drug use, the therapy planning has to aim at school and occupational rehabilitation and integration from the very beginning and should not declare secondary goals, such as an optimal fit into a therapy commune or reappraising family therapy discussions, as apparent main goals.

It can rarely be assumed that the adolescent has sustained intrinsic motivation, which is why it is essential to involve the custodial parents or a guardian and to cooperate with the competent regional child and adult protection authorities (KESB) and, if necessary, with the youth ombudsman’s office. In this context, criminal charges or ongoing proceedings must be taken into account, as well as debts and financial dependency situations – both topics that are often neglected in medical diagnostics and later have a significant impact on the course of therapy. Involvement of the family or important close caregivers is advisable in almost every case (see [10]), especially since, in addition to the custody issue, the family system dynamics can also be important for the course of the case. Specific therapy methods such as Multidimensional Family Therapy (MDFT, [11]) are also among those with the highest levels of evidence.

The evidence of pharmacological interventions is de facto non-existent; medication is based on individual symptoms or comorbidity.

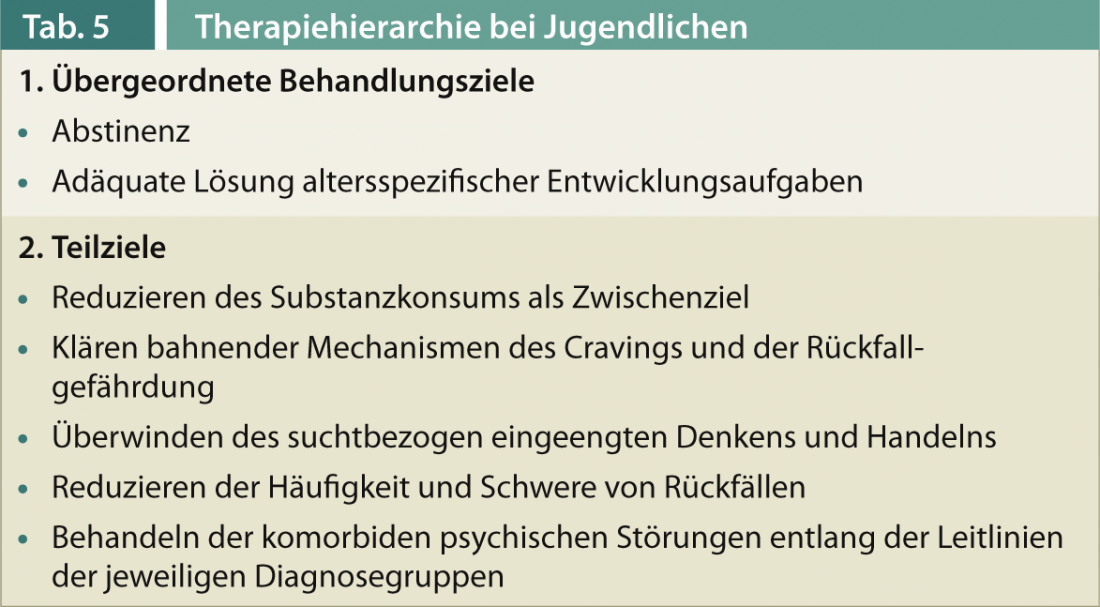

The basic therapy goals (Tab. 5) focus – and this closes the circle – on the upcoming developmental tasks.

Oliver Bilke-Hentsch, MD MBA

Literature:

- Jordan S, Sack PM: Protection and risk factors, in Thomasius R, et al. (eds.): Addictive disorders in childhood and adolescence. Stuttgart, Schattauer 2009; 127-137.

- Monitoring Report Addiction Switzerland 2013 (www.suchtschweiz.ch).

- Reis O: Risk and protective factors of addiction development, developmental dynamic aspects, in: Batra A , Bilke-Hentsch O (eds.): Praxisbuch Sucht. Stuttgart, Thieme 2011; 8-15.

- Esser G, et al: A developmental model of substance abuse in early adulthood. Childhood and Development 2008; 17: 31-45.

- Batra A, Bilke-Hentsch O: Praxisbuch Sucht. Stuttgart, Thieme 2011.

- Prohaska JO, Di Clemente CC: Towards a comprehensive model of change, in Miller WR, Heather N (eds.): Treating addictive behaviours. New York, Plenum, 1985; 3-27.

- Remschmidt H, Schmidt MH (eds.): Multiaxial classification scheme for childhood and adolescent mental disorders according to the WHO ICD-10. 4th ed. Bern, Huber 2004.

- German Society for Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychotherapy (eds.): Guidelines on Diagnosis and Therapy of Mental Disorders in Infancy, Childhood and Adolescence. 2nd ed. Cologne, Deutscher Ärzte-Verlag 2006.

- AACAP Official Action: Practice Parameters for the Assessment and Treatment of Children and Adolescents with Substance Use Disorders. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005; 44: 609-621.

- Klein M. (eds.): Children and the risks of addiction. Stuttgart, Schattauer 2008.

- Spohr B, Gantner A.: Multidimensional family therapy – a combination of family therapy and addiction therapy for adolescents with addictive disorders and behavioral problems. Psychoth in Dialog PID 2010; 3: 254-260.