Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common valvular disorder which can occur at all ages. It is the most frequent cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries. MVP is associated with significant morbidity in symptomatic patients, whereas the uncomplicated form of MVP has a benign natural history. Mitral regurgitation (MR) due to MVP can be repaired with a low risk of mitral regurgitation recurrence and reoperation. Early surgery is associated with low surgical risks and better outcomes.

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common valvular disorder which can occur at all ages. It is associated with valve thickening, annulus dilation and abnormal chordae tendineae [1]. Mitral valve prolapse has been recognized as a clinical entity for some 60 years, when Barlow and Bosman used cineangiography. Before this period, the general opinion was that systolic clicks and murmurs are caused by pericardial adhesions, and the advanced stage of the disease with progressive mitral regurgitation was frequently misdiagnosed with rheumatic heart disease. However, with the arrival of two-dimensional (2D) echocardiography the natural history and pathophysiology of the MVP and its complications became manifest. The term MVP was originally coined by Criley et al [2], and is now recognized as the major cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries. If not diagnosed and appropriately managed, the MVP can be a cause of premature mortality and considerable morbidity.

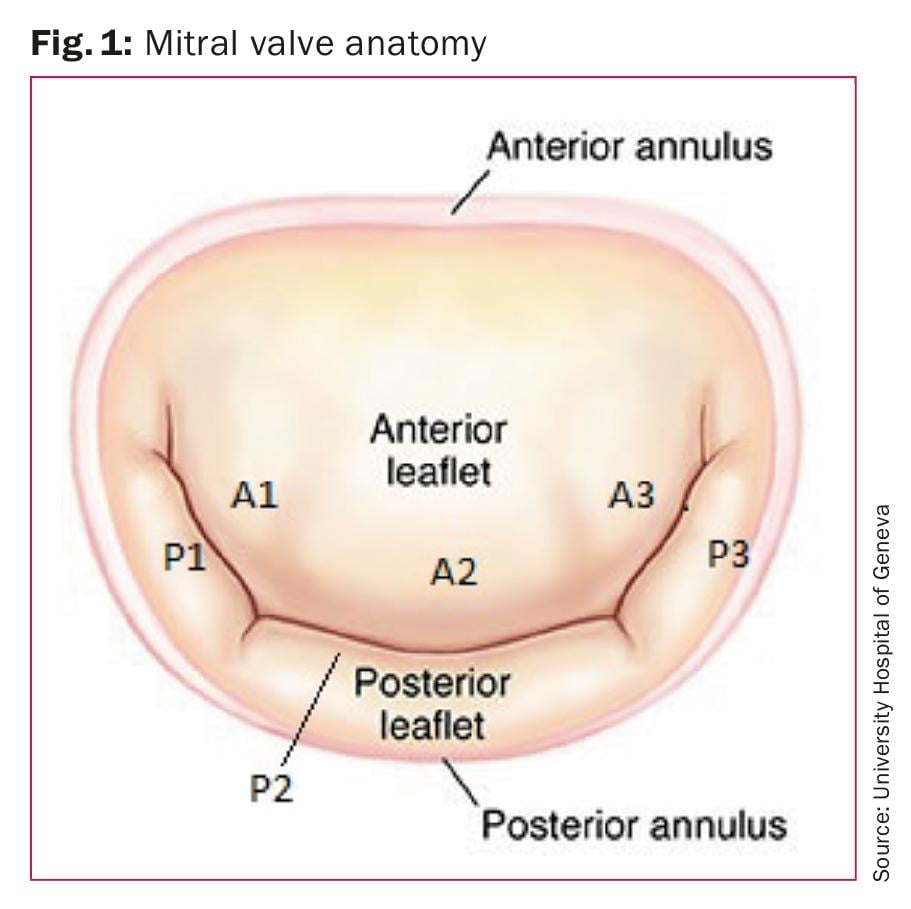

Mitral valve anatomy

A basic knowledge of the anatomy of the normal mitral valve (Fig. 1) is important to understand the variable presentation and mechanism of mitral valve prolapse. The mitral valve consists of anterior and posterior leaflets attached at their bases to a fibrous or fibromuscular ring, the mitral annulus. The leaflets are attached to the two papillary muscles (anterolateral and posteromedial) by chordae tendineae. One of the functions of the chordae tendineae is to prevent eversion or prolapse of the leaflets in systole. The anterior leaflet is generally larger than the posterior, has a narrower base and is triangular. The posterior leaflet is shorter, and segmented into three scallops or segments: lateral, middle, and medial. Although the middle scallop is the largest, there is considerable variability. The anterior and posterior leaflets meet at two commissures: posteromedial and anterolateral.

Carpentier classification: Alain Carpentier [3] has proposed a surgical classification of mitral valve anatomy. In this classification, the three scallops of the posterior leaflets are referred to as P1 (anterolateral), P2 (middle), and P3 (posteromedial). The corresponding segments of the anterior leaflet are labelled A1, A2, and A3 (Fig. 1).

Mitral valve prolapse – Definition, Classification

Mitral valve prolapse (MVP) is a common valvular disorder defined as the systolic billowing of one or both mitral leaflets into the left atrium, with or without mitral regurgitation. It is the most frequent cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries and the most common primary cause for dysfunction requiring mitral valve repair or replacement [4,5].

MVP is classified as an inheritable connective tissue disorder that is regarded as an autosomal dominant disorder with variable penetrance. It is divided into primary and secondary MVP [6]. Primary MVP is generally associated with myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve (MV). Secondary MVP is caused by chordae tendineae rupture and/or abnormal left ventricular (LV) wall motion. Potential causes of secondary MVP include coronary artery disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathies, and infective endocarditis. MVP may also be associated with some heritable disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, the Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or the Loeys-Dietz syndrome.

Boudoulas et al. [7] proposed a «clinical classification» of MVP and divided MVP into two groups: anatomic MVP and syndromic MVP.

Pathology and pathophysiology

MVP is characterized by progressive enlargement of the mitral valve annulus and thickening of leaflets and chordae causing leaflets to prolapse superiorly into the left atrium beyond the mitral annulus in systole, leading to MR. Histologically, the mitral valve leaflets in MVP present myxomatous degeneration with collagen breakdown and production of abnormal collagen fibrils.

It is known that special genes have important roles in the formation of the heart valves: calcineurin, Wnt/beta-catenin, fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-4, Sox4, and TGF-β. Defects in one or more of these genes and their signalling cascades may cause myxomatous changes and weakening of the valves. It is reported that TGF-β up-regulation has an important role in the pathogenesis of both anatomic or non-syndromic MVP and syndromic MVP [8].

Natural History and Epidemiology

MVP is the leading cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries with a prevalence of about 2,4% of the population. MVP has been detected in many population groups of different ethnic and racial backgrounds. Marks et al. [9] reported that patients with thickened and redundant valves had an increased risk of infective endocarditis, MR, and MV replacement.

The age of onset of MVP is variable. Clinical manifestations rarely occur before adulthood, and surgical intervention for severe MR is most likely in the sixth or seventh decade. The average time from detection of a murmur to symptomatic presentation is about 20–25 years [6,10].

The presence of MR leads to progressively more severe MR, as initial level of MR causes LV dilatation, which increases stress on the mitral apparatus. This stress causes further damage to the valve apparatus, resulting in more severe MR and further LV dilatation, thus proceeding a perpetual cycle of ever-increasing LV volumes and MR. This volume overload leads to irreversible LV dysfunction and a poor prognosis.

Symptoms

Most patients with new diagnosed MVP are asymptomatic, and the diagnosis is often based on cardiac auscultation or because of an unexpected echocardiographic finding. The common symptoms of patients with MVP are shortness of breath, palpitations, chest discomfort and the symptoms of heart failure when significant MR is already present. Some patients may present sudden onset of these symptoms which may result from acute chordal rupture or from valve leaflet perforation or valve disruption in endocarditis.

Echocardiographic Diagnosis

2D echocardiography is a standard diagnostic technique for precise diagnosis of MVP and to determine the presence of MR and other findings that affect prognosis and risk of complications. The transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and three-dimensional (3D) echocardiography may give supplementary information on the evaluation of the mitral valve apparatus. Stress echocardiography may help to differentiate moderate from severe MR by generating additional diagnostic and prognostic information in selected patients.

On 2D echocardiography, MVP is diagnosed when one or both of the leaflets are displaced 2 mm or more in systole above a line connecting the annular hinge points in parasternal or apical long-axis view [5,11].

Complications of MVP

MVP is associated with significant morbidity in symptomatic patients, whereas the uncomplicated form of MVP has a benign natural history. Most common complications of MVP are endocarditis, sudden cardiac death, arrhythmias, cerebrovascular events, and severe MR with surgical indication.

The risk of infectious endocarditis is five times greater in patients with MVP than in the general population [12], but the absolute risk is small, at approximately 0,2% per year. Risk factors for the development of infective endocarditis in patients with MVP include male gender, age over 45 years, the presence of a systolic murmur, valvular thickness.

Cardiac arrhythmias are frequently detected in patients with MVP. Atrial fibrillation is one of the most common complications of the MVP. Paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia is the most common tachyarrhythmia. Most arrhythmias that are identified in patients with MVP are benign; however, some cases with ventricular arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death (SCD) have been reported. Ventricular arrhythmias and SCD are the most serious complication of MVP. The estimated rate of SCD in MVP ranges from 0,2%/y to 0,4%/y in different prospective studies [13,14]. Corrado et al. [15] studied 200 consecutive cases of sudden death (age ≥35 years) and found that most patients with MVP (10% of the total) were asymptomatic women without significant mitral valve regurgitation. Basso et al. [14] examined the registry of 650 young adults (age ≤40 years) with SCD and found that MVP is an important cause of arrhythmic SCD, mostly in young adult women (7% of all SCD, 13% of women).

MVP is the most frequent cause of mitral regurgitation, with development of MR in about 10% of isolated MVP [6,7], resulting from progressive myxomatous leaflet degeneration, redundancy of the chordae tendineae and enlarging of the mitral annulus. However, the general contribution of these factors is unclear. Not all patients with MVP progress to severe MR, the progression often is slow over an average of 25 years [10]. Severe MR may have an acute onset due to ruptured chordae tendineae or infective endocarditis. Men over the age of 45 years with MVP have a two to three times higher risk of developing severe MR that ultimately requires surgery. Once severe MR is established, the volume overload leads to progressive enlargement of left atrial and LV chambers, resulting in atrial fibrillation, pulmonary hypertension and congestive heart failure [6,7].

Management of Mitral Valve Prolapse

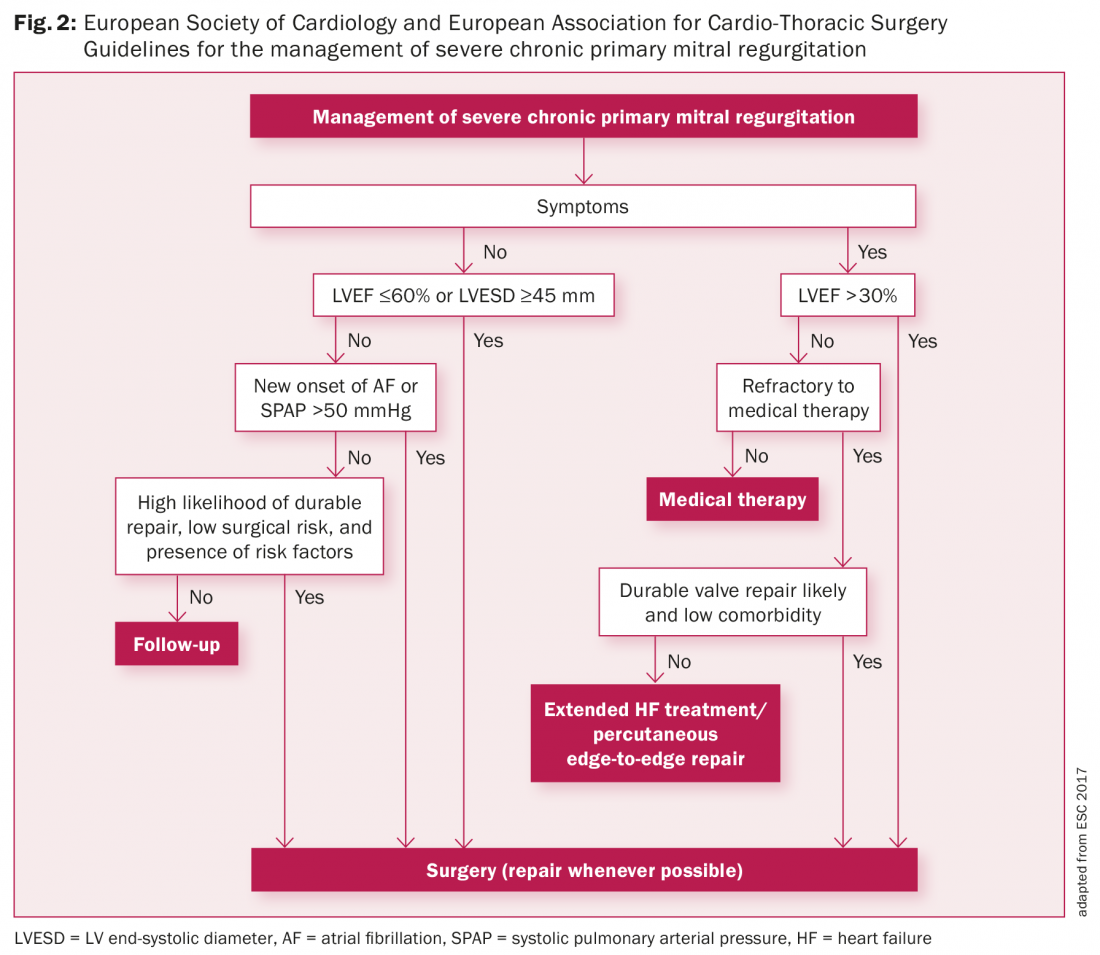

Asymptomatic patients with MVP or those with only mild symptoms, no arrhythmias, a normal ECG, and no evidence of MR have an excellent prognosis and generally a benign natural history. Asymptomatic patients with moderate MR and preserved LV function should have follow-up on a yearly basis with echocardiographic control every 1–2 years. Asymptomatic patients with severe MR and good LV function (LVEF >60%) should have a clinical and echocardiographic follow-up every six months. If they reach guideline indications for MV surgery (Fig. 2), early surgery is associated with low surgical risks and better outcomes [16–18].

In symptomatic MVP medical treatment with ACE-inhibitors, Beta-blockers and spironolactone (or eplerenone) is considered in patients with symptoms of heart failure who are not suitable for surgery or when these symptoms persist after surgery. Patients with ventricular arrhythmias or palpitations associated with dizziness and/or syncope should have a careful family history review for SCD. It is recommended for these patients to have a 24-hour ambulatory monitoring (Holter) and stress testing for possible arrhythmia detection. Patients with chronic or paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, whether or not arterial embolism has occurred, are recommended to have anticoagulation therapy (e.g. Sintrom, Warfarin) if not contraindicated.

Surgical intervention

In Figure 2 we present the latest guidelines of the European Society of Cardiology and European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery for the management of severe primary mitral regurgitation. Symptomatic patients with severe mitral regurgitation (MR) should be considered for MV surgery [16]. It has been reported that long-term survival after mitral valve reconstruction is less favourable in patients with New York Heart Association (NYHA) Class III or IV than in patients with NYHA Class I or II [17,18]. Early surgery is associated with better outcomes. Surgical indications for patients with severe MR are LVEF ≤60% or LV end-systolic diameter (LVESD) ≥45 mm, new onset atrial fibrillation and a systolic pulmonary pressure ≥50 mmHg [16].

There is no randomized comparison between the results of valve replacement and repair, but it is widely accepted that, when feasible, valve repair is the preferred approach. Mitral regurgitation due to mitral valve prolapse can be repaired with a low risk of mitral regurgitation recurrence and reoperation. Preoperative transesophageal echocardiography has an important role in diagnosis of the severity of MR and may give supplementary information on the evaluation of the mitral valve apparatus. Intraoperative transesophageal echocardiography should be used to evaluate the result of MV repair.

Surgical technique – valve repair

It is broadly accepted that the majority of patients with mitral valve prolapse and severe regurgitation can undergo successful repair using different techniques. Proper analysis of all segments of MV and subvalvular apparatus is important for MV reconstruction. The aim of valve reconstruction is to achieve durable normal valve function. There are three basic principles of mitral valve repair [19]: normal leaflet motion, large surface of leaflet coaptation and remodeling of the mitral valve orifice as well as stabilisation of the mitral annulus. The goal of MV plasty for MVP is to correct the prolapse and to transform the posterior leaflet into a smooth, regular, and vertical buttress parallel to the posterior wall of the left ventricle. Many surgical techniques have been developed to correct MVP. Because of the great variability of the dysfunction and lesions, and of quality of the leaflet tissue, it is difficult to recommend standardized techniques for the repair. The choice of technique depends on many factors, such as extent of the prolapse, degree of prolapse and the lesions producing the prolapse. The «one lesion one technique principle» proposed by Carpentier [3,20] facilitates the choice between the different surgical techniques. In all techniques of mitral valve repair which involve the subvalvular apparatus, remodeling of the mitral valve with annuloplasty is necessary to reduce tension on the sutures [19].

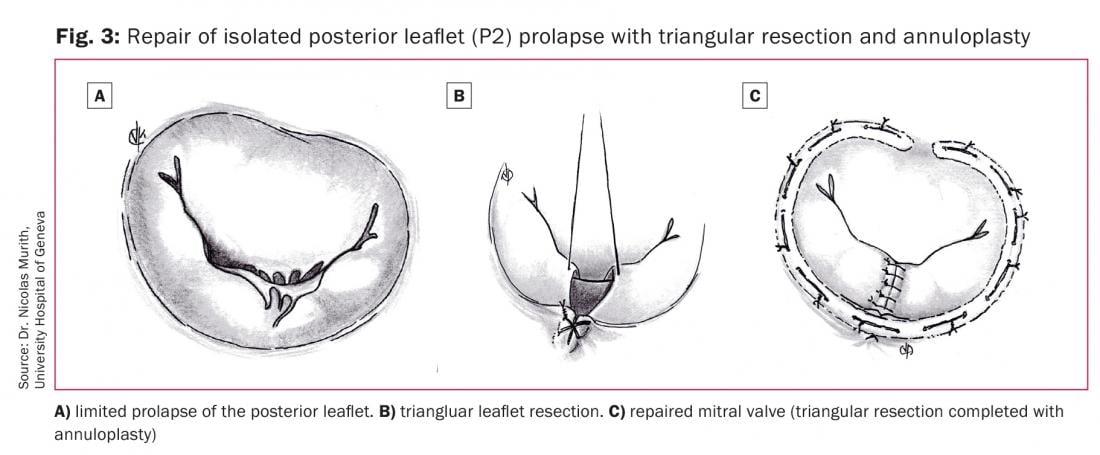

A limited prolapse of the anterior or posterior leaflet (Fig. 3A) can be treated by triangular leaflet resection. The prolapsed area is identified, two hooks or sutures passed around the non-elongated chordae at the limits of the prolapsed area and after gentle traction, the created triangle of tissue is identified. A 5-0 suture is placed on top of the triangle and the tissue is then resected (Fig. 3B). The two new created edges of the leaflet are then sutured by 4-0 or 5-0 polyester sutures using everted or inverted sutures (Fig. 3C). For the anterior leaflet prolapse, the resection area should not involve more than 10% of the leaflet surface area [19].

If there is a non-elongated secondary chorda less than 5 mm from the free edge of a prolapsed segment of the anterior leaflet, a leaflet fixation could be done with two 5-0 monofilament sutures passing through the chorda and then through the leaflet free edge.

For the posterior leaflet prolapse, the triangular resection is indicated when the length of the free edge of the prolapsed segment is not more than one third of the total length of this segment. If more than one third of the length is involved by extensive posterior leaflet prolapse, a quadrangular resection and annular plication can be performed. The resection area should not involve more than 40% of the posterior leaflet area. In case of more extensive prolapse, a composite technique of partial posterior leaflet resection associated with chordae repair can be used.

Triangular leaflet plication or triangular resection can be used in case of limited prolapse involving ≤5 mm of the commissural edge. In case of extensive commissural prolapse caused by chordae rupture, a quadrangular resection can be performed. If the posterior commissure is involved, the quadrangular resection is completed by annular plication and the «magic stitch» by Carpentier, when the prolapsed area is 5–10 mm. If prolapse is greater than 10 mm, the quadrangular resection is completed by sliding leaflet plasty [19]. At the anterior comissure, the quadrangular resection generally is completed by sliding leaflet plasty.

Acute MV regurgitation can occur after myocardial infarction or trauma due to MVP caused by papillary muscle rupture. Generally, this condition requires an emergency surgical operation, in most instances MV repair is difficult or not possible, therefore a valve replacement is necessary. However, in some cases the MV repair can be done. Papillary muscle reimplantation, papillary muscle head reimplantation or muscle shortening technique can be used depending on the type of lesion.

In case of extensive bi-leaflet prolapse, a combination of these techniques should be used to achieve a good result.

In situations with extended bi-leaflet prolapse, or presence of the multiple regurgitant jets, when the anatomical reparation is difficult or not possible, an «edge-to-edge» surgical repair technique can be performed, which consists of suturing together the facing portions of the anterior and posterior mitral valve leaflets [21].

Occasionally, after all the major corrections have been accomplished, there may remain some commissural prolapse at the junctions of the leaflets. This can be often corrected with lateral Alfieri-type stitches or a Carpentier «magic stitch», or by lateral comissuroplasty. The surgical success and late outcomes of the mitral valve plasty are determined by employment of the correct surgical approach for a given pathology. In all cases of surgical mitral valve repair the mitral valve annulus is stabilised by a annuloplasty using a closed rigide or semi-rigide annuloplasty device. Failure to support the mitral annulus with a annuloplasty increases the rate of MR recurrence.

Mitral valve replacement

Mitral valve replacement with biologic or mechanic prosthesis can be performed when reconstruction is not satisfying or might not result in long-lasting repair success.

Conclusion

Mitral valve prolapse can occur at all ages and it is the leading cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries. The majority of patients with mitral valve prolapse and severe regurgitation can undergo successful repair. Mitral valve repair for mitral valve prolapse is a low-risk, durable surgical procedure. Outcomes and long-term survival after mitral valve repair are better if patients are referred early to surgery.

Take-Home-Messages

- MVP is the most frequent cause of mitral regurgitation in developed countries.

- 2D echocardiography is a standard diagnostic technique for precise diagnosis of MVP.

- Mitral regurgitation (MR) due to MVP can be repaired with a low risk of mitral regurgitation recurrence and reoperation.

- Early surgery is associated with low surgical risks and better outcomes.

- When feasible, valve repair is the preferred approach.

Bibliography:

- Otto MC, Bonow OR: Valvular Heart Disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2014.

- Criley SM, et al.: Prolapse of the mitral valve: Clinical and cineangiographic findings. Br Heart J 1966; 28: 488–496.

- Carpentier A: Cardiac valve surgery — the «French correction». J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 1983; 86: 323—37.

- Braunwald E: Mitral valve prolapse. In: Braunwald’s heart disease: a textbook of cardiovascular medicine, Philadelphia: WB Saunders 1997; 5(2): 1029–1035.

- Guy FC, et al.: Mitral valve prolapse as a cause of hemodynamically important mitral regurgitation. Can J Surg 1980; 23: 166–170.

- Jacobs W, Chamoun A, Stouffer GA: Mitral Valve Prolapse: A Review of the Literature. Am J Med Sci 2001; 321(6): 401–410.

- Boudoulas H, et al.: Mitral valve prolapse and the mitra valve prolapse syndrome. Am Heart J 1989; 118: 796–818.

- Delling FN, Vasan RS: Epidemiology and Pathophysiology of Mitral Valve Prolapse: New Insights into Disease Progression, Genetics, and Molecular Basis. Circulation 2014; 129(21): 2158–2170.

- Marks AR, et al.: Identification of high-risk and low-risk subgroups of patients with mitral valve prolapse. N Engl J Med 1989; 320: 1031–1036.

- Cohen IS: Two-dimensional echocardiographic mitral valve prolapse: evidence for a relationship to echocardiographic morphology to clinical findings and to mitral annular size. Am Heart J 1987; 113: 859–868.

- Shah, PM: Current concepts in mitral valve prolapse – Diagnosis and management. J Cardiol 2010; 56(2): 125–133.

- Hickey RJ, MacMahon SW, Wileken DEL: Mitral valve prolapse and bacterial endocarditis: when antibiotic prophylaxis necessary? Am Heart J 1985; 109: 431–435.

- Nishimura RA, et al.: Echocardiographically documented mitral-valve prolapse: long-term follow-up of 237 patients. N Engl J Med 1985; 313: 1305–1309.

- Basso C, et al.: Arrhythmic Mitral Valve Prolapse and Sudden Cardiac Death. Circulation 2015; 132(7): 556–566.

- Corrado D, et al.: Sudden death in young people with apparently isolated mitral valve prolapse. G Ital Cardiol 1997; 27: 1097–1105.

- Baumgartner H, et al.: 2017 ESC/EACTS Guidelines for the management of valvular heart disease. Eur Heart J 2017; 38(36): 2739–2791.

- Tribouilloy CM, et al.: Impact of preoperative symptoms on survival after surgical correction of organic mitral regurgitation: rationale for optimizing surgical indications. Circulation 1999; 99(3): 400–405.

- Mohty D, Enriquez-Sarano M. The long-term outcome of mitral valve repair for mitral valve prolapse. Curr Cardiol Rep 2002; 4(2): 104–110.

- Carpentier A, Adams D, Filsoufi F: Carpentier’s Reconstructive valve surgery. 1st ed. Saunders; 2010.

- Carpentier A, et al.: Conservative management of the prolapsed mitral valve. Ann Thorac Surg 1978; 26(4): 294–302.

- Maisano F, et al.: The edge-to-edge technique: a simplified method to correct mitral insufficiency. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 1998; 13(3): 240–245; discussion 245–246.

CARDIOVASC 2017; 16(6): 10–15