By no means every patient who visits the doctor with swellings of the large salivary glands suffers from a viral or bacterial inflammation. The cause of swelling can also be a salivary stone. This must be recognized and diagnosed at an early stage so that the patient can be quickly and adequately given the right therapy. The leading symptom of salivary stone disease is always an increase in swelling of the affected gland and discomfort during eating.

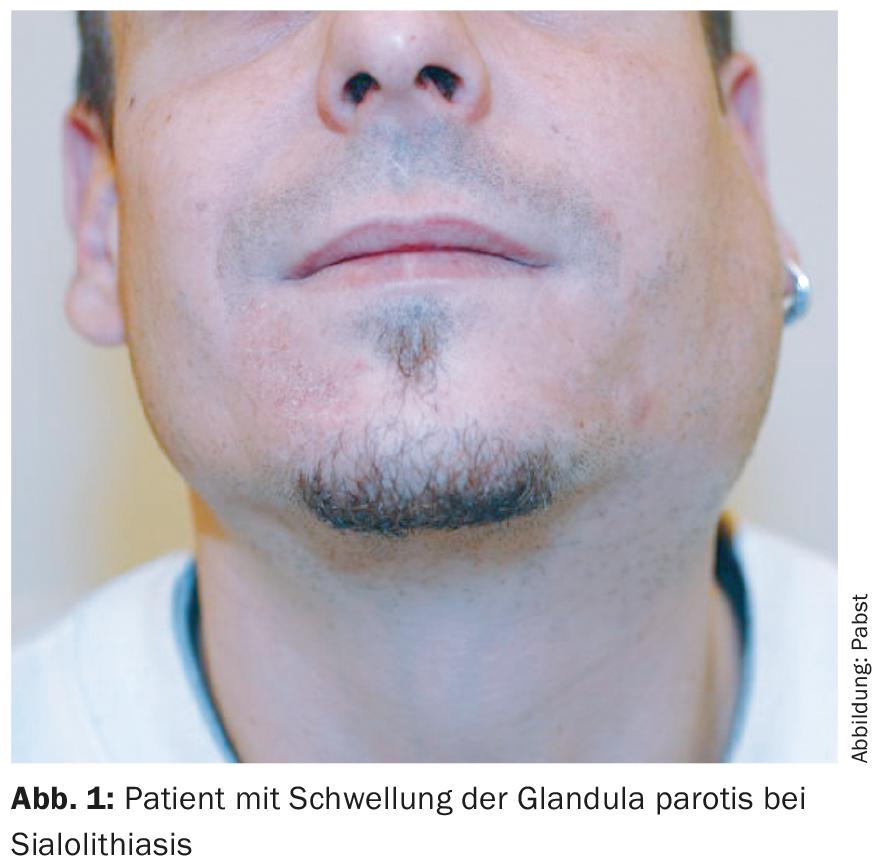

Patients with swelling of the major salivary glands frequently come to the practice (Fig. 1) . In many cases, the cause is assumed to be a viral or bacterial inflammation, which is followed by antiphlogistic or antibiotic therapy. However, the actual cause often remains unclear.

Stenoses in the salivary ducts or else sialolithiasis are often diagnosed only after several episodes of unclear salivary gland swelling, and in the case of salivary gland swelling lasting only a short time, the patient’s statements are regarded as questionably credible because the finding is no longer seen when the patient presents to the physician. For this reason, it is important to know the diagnosis and symptoms of salivary stones in order to quickly and adequately guide the patient to the right therapy.

What are salivary stones and how do they form?

Salivary stones are the most common cause of salivary gland inflammation [3]. The stones, which are 2 mm to 2 cm in size, consist of calcium phosphate and carbonate and are mostly found in the glandular hilus of the affected gland. In 70% of cases the submandibular gland is affected, in about 30% the parotid gland. Exactly how salivary stones are formed is unclear at this time. However, it is assumed that possibly after small inflammations in the glandula, corresponding small stenoses or depressions form in the ductal system, in which the suspended matter from the saliva is deposited. This would also explain why the submandibular gland is more frequently affected than the parotid gland, since the glandular duct (Warthon’s duct) is ascending here and the saliva has a higher viscosity.

Salivary stones can be found in about one percent of the population, but they usually go unnoticed until the onset of discomfort when eating. A correlation to kidney stones or a development through the consumption of calciferous water could not be proven until now.

Medical history and clinical examination

In the history, the patient reports a rapid onset of swelling of the corresponding gland, which often resolves on its own after minutes to hours. After blockage of a glandular duct by a salivary stone, saliva backs up into the gland. The affected gland then swells, especially when eating or salivating substances, and the pain of gland swelling is increased because more saliva is produced. Prolonged salivary gland congestion can lead to bacterial superinfection, which is extremely painful. Further complications such as abscesses or inability to eat may develop as a result. Fever or skin redness, possibly even fistulas after enoral or through the skin after an abscess, may occur.

The complaints are often confused with symptoms of temporomandibular joint arthritis or with mumps. The first examination step is performed by the ENT physician by means of clinical examination. Palpation of the floor of the mouth or cheek and, depending on the location and size of the stone, the stone can often be identified by bimanual palpation. At the same time, the affected gland is bimanually smoothed out; the caruncula of the respective excretory duct can be used to assess whether there is total blockage without salivation or whether thickened, possibly purulent secretion is expressible as a sign of infection.

Imaging diagnostics

Submandibular stones are more likely to be radiopaque than parotid stones because they have a higher calcium content. The detection of these stones can be optimized by intraoral settings compared to the standardized extraoral settings used in radiography. Nevertheless, the concretions are often mistaken for tissue calcifications or exostoses, especially on conventional radiography. Computed tomography can circumvent some of these disadvantages, but again, of course, some stones are not radiopaque.

MR sialography, in which saliva can be used as a natural contrast medium by skilful choice of examination parameters, also shows multiple concretions in the gland as well as in the excretory duct with good resolution. The disadvantage of this method is the poor availability of the very costly examination.

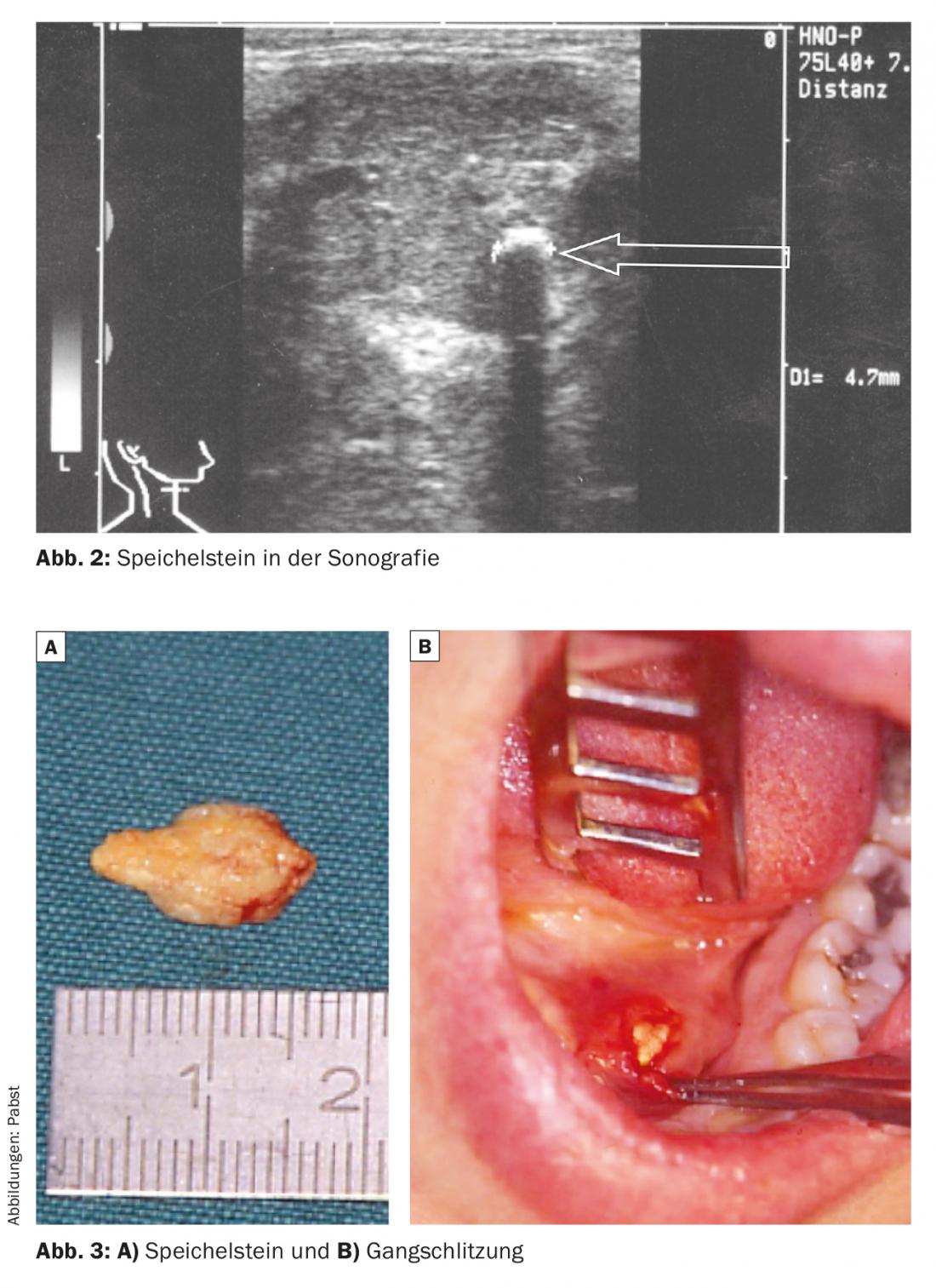

Sonography has been shown to be the method of choice for sialolithiasis [2,3,5]. It is a non-invasive, readily available, low-cost examination method that is not very burdensome for the patient. However, sonography requires a certain amount of experience on the part of the examiner and this is its greatest disadvantage. In return, it shows high sensitivity and allows accurate topographic stone localization in relation to adjacent anatomical structures. Concretions between 1 and 2 mm are mostly detectable independent of the calcium content due to the ultrasound heads between 7.5 and 13 MHz that are frequently used today. In addition, dorsal ductal congestion indicates stenosis in the ductal system (Fig. 2).

Conservative treatment of salivary stones

If glandular congestion occurs due to obstruction of the duct, antiphlogistic treatment and sialogoga and glandular massage can be used initially for two to three days. Salivary duct probing also sometimes already brings relief. If the stone is located near the entrance, especially in Warthon’s duct, salivary duct slitting can be performed as first-line therapy (Fig. 3). If the infection parameters are increasing after two days and the duct congestion continues, antibiotic therapy should be started, otherwise there is a risk that the inflammation will spread.

Shock wave treatment, sialendoscopy or removal of the salivary gland.

If the concretion is located in the region of the glandular hilus or in the gland itself or in the proximal ductal system, three forms of therapy may be considered.

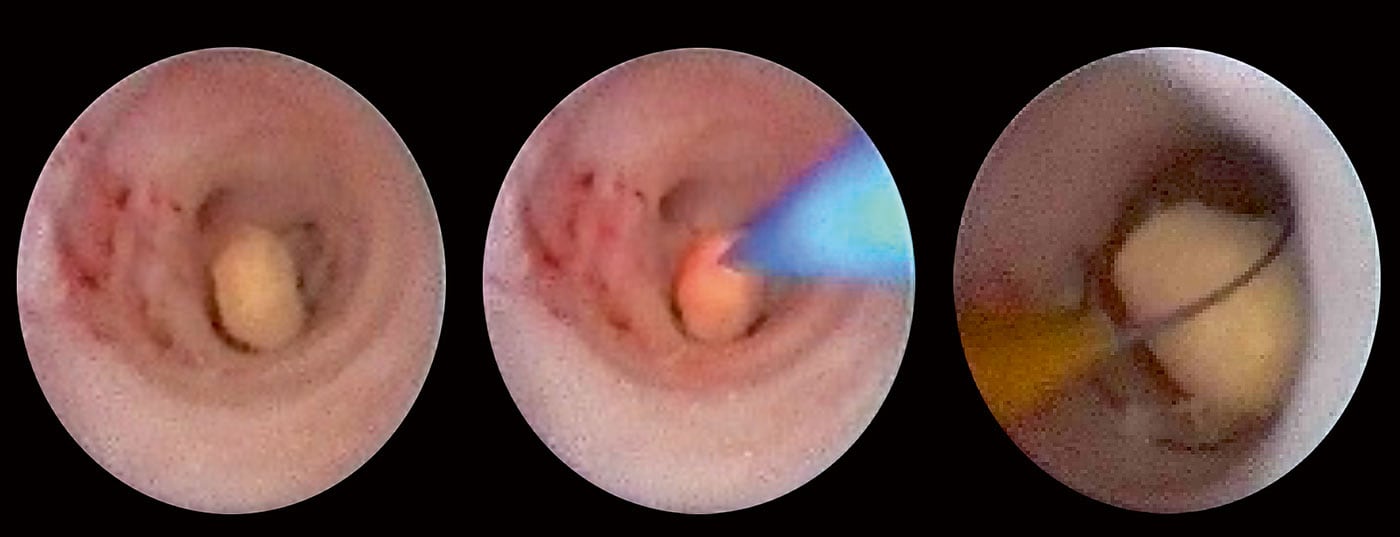

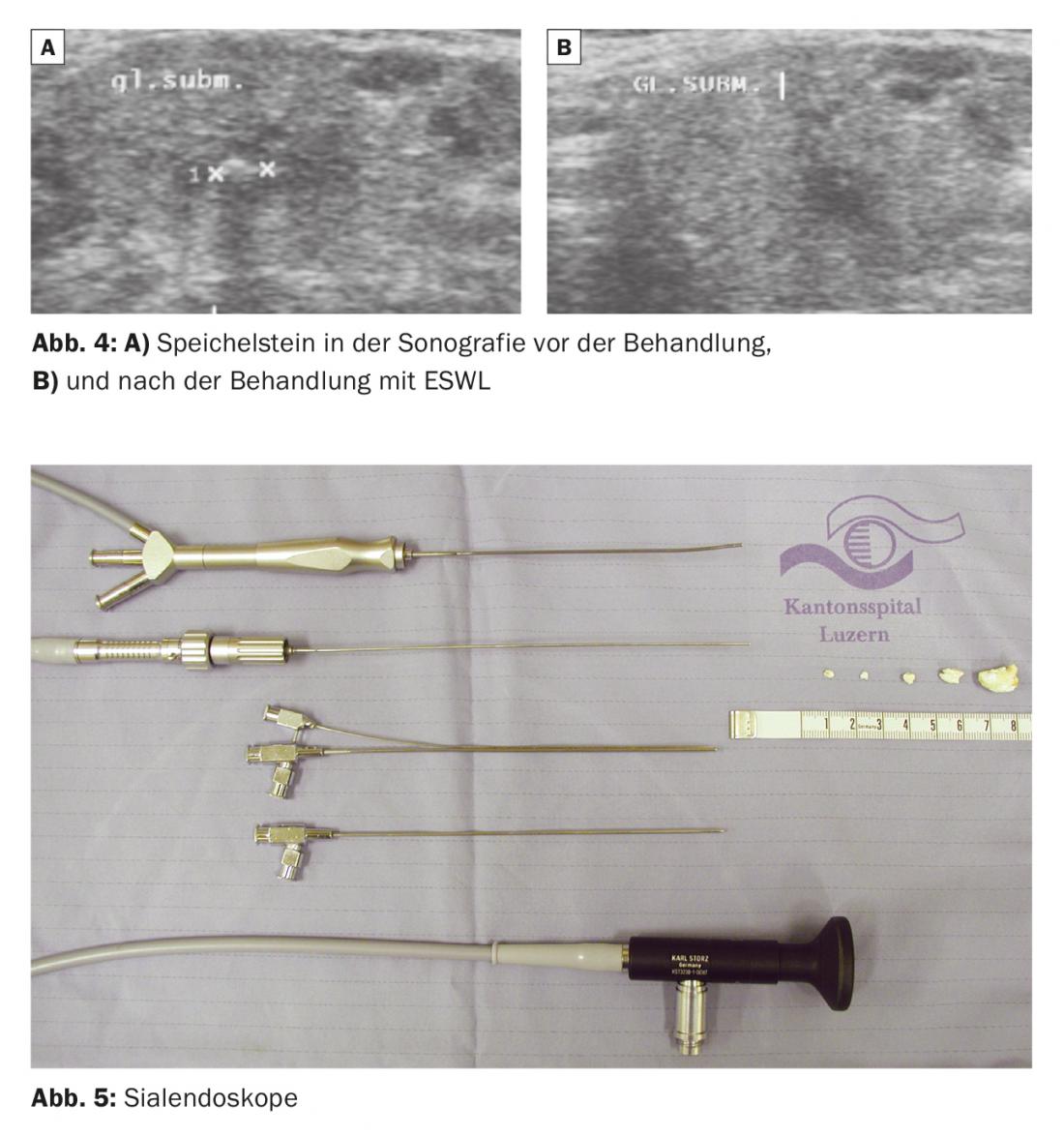

- Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (lithotripsy, ESWL): the patient undergoes shock wave treatment on the stones diagnosed by ultrasound, analogous to the treatment of kidney stones [5]. It is a gentle, low-pain, outpatient procedure that is usually performed three times at monthly intervals. ESWL may only be used in the inflammation-free stage. The success rate is between 60 and 70% depending on size, composition, location and salivary gland (Fig. 4) [2]. Since ESWL is a non-invasive form of therapy, it is preferred to surgical procedures whenever possible.

- Sialendoscopy (endoscopic salivary stone removal transductally): This is a minimally invasive operation, whereby the procedure is performed transductally using a 1-2 mm endoscope (Fig. 5) [1–5]. Intraglandular stones can be fragmented (e.g., by laser) and the stone fragments removed by means of hooks, insertion of baskets or tines (Fig. 6). The advantage of this surgical method is that it is a low-risk surgical procedure without endangering the facial nerve and can usually be performed on an outpatient basis. The success rate is about 80%.

- Salivary gland removal: The submandibular gland or parts of the parotid gland can be surgically removed. However, there is a risk of facial nerve damage, ranging from 7 to 17% depending on the literature [5]. Fortunately, this form of therapy can be considered ultima ratio, which today needs to be performed in only a few cases.

Conclusion for practice

First of all, it is important to know and diagnose a salivary stone condition. Here, the leading symptom is always an increase in swelling of the affected gland and discomfort when eating. In addition to anamnesis and clinical examination, sonography is primarily suitable for establishing the diagnosis. In the hands of a trained examiner, sonography shows a high sensitivity for salivary stones. After conservative therapeutic approaches using sialogoga and glandular massage, the simplest surgical therapy for stones near the entrance remains salivary duct slitting. Gland removal, with its not inconsiderable risks to the facial nerve, has been therapeutically displaced by newer, gentler treatment methods, particularly extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy and sialendoscopy, which can be performed both diagnostically and interventively.

Second reprint with kind permission of “Dimensions” magazine

Literature:

- Geisthoff U: Salivary gangendoscopy. HNO 2008; 56: 105-107.

- Zenk J, et al: [The significance of extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy in sialolithiasis therapy]. HNO 2013; 61: 306-311.

- Koch M, Zenk J, Iro H: Salivary gangendoscopy in the diagnosis and therapy of obstructive salivary gland diseases. HNO 2008; 56: 139-144.

- Marchal F, Dulguerov P: Sialolithiasis Management: The State of the Art. Arch Laryngo-Rhino-Otol Head Neck Surg 2003; 129: 951-956.

- Pabst G, Reimers M: Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy (EWSL) and sialendoscopy. The Lucerne treatment concept for sialolithiasis. Switzerland Med Forum 2004: Suppl 16, 119-121.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(6): 26-30