Actinic keratoses are a marker of chronic sun damage and carcinogenesis of the skin. Sun protection, especially at a young age, is the most important primary prevention measure against actinic keratoses in the case of chronic UV exposure. Early treatment of actinic keratoses is indicated. A variety of treatment options are available.

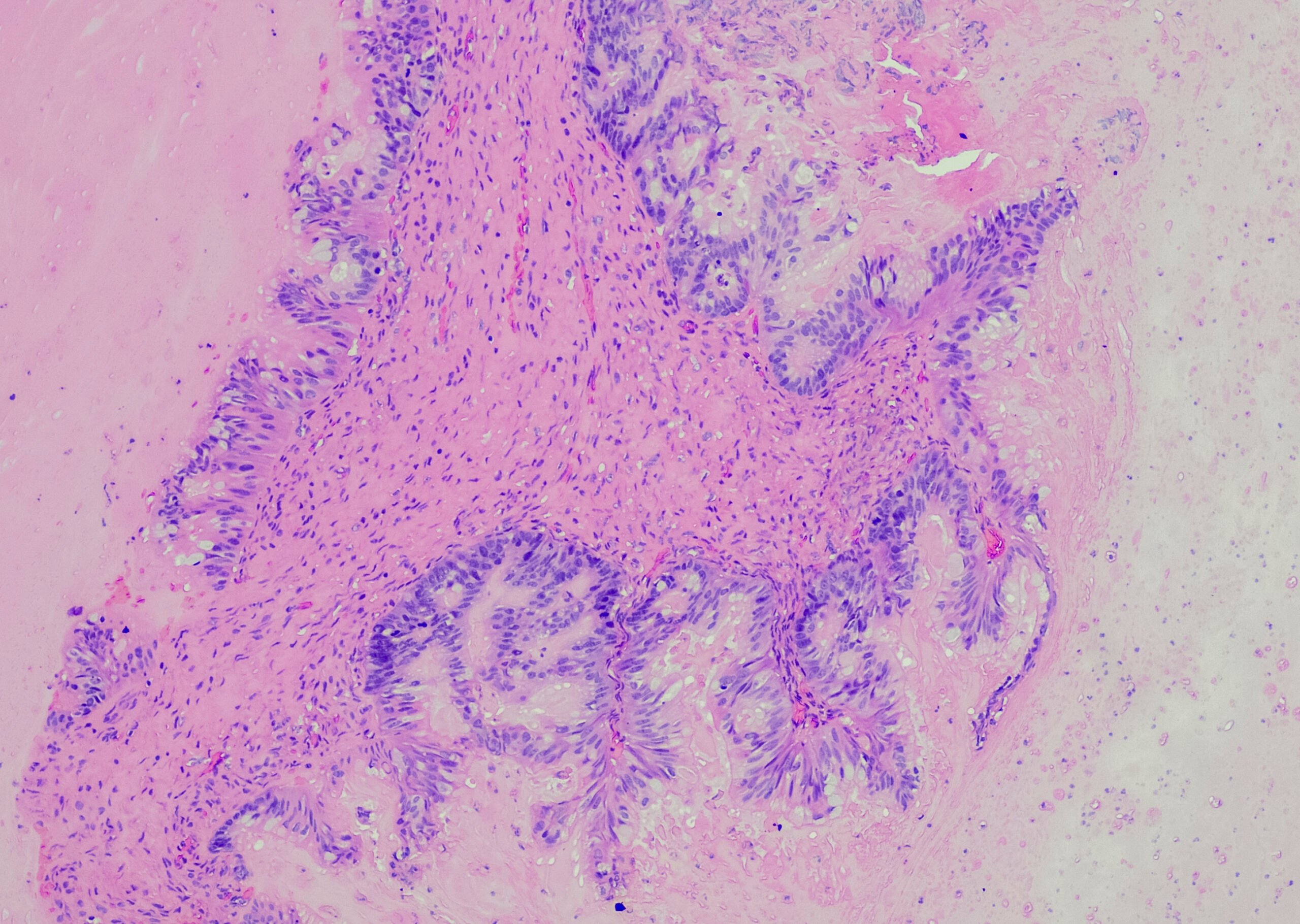

Actinic or solar keratosis (AK) represent in situ squamous cell carcinomas of the skin and are among the more common dermatoses seen in daily practice. As the name suggests, the sun resp. UV radiation, especially UV-B, is responsible for their formation. Primarily chronic UV exposure leads cumulatively to permanent and increased DNA and genome damage of the skin (especially mutation of the tumor suppressor gene p53), the consequence of which is then a more or less pronounced mitosis-rich proliferation of transformed dyskeratotic keratinocytes.

It has been known for some time that individuals with occupational UV exposure (“outdoor workers”) are significantly more likely to have AK than those who work primarily in offices. However, in addition to the intensity of UV radiation, the skin type of the person exposed to UV radiation also contributes to the risk of developing AK. Therefore, much higher prevalences are observed in regions with high UV irradiation and fair-skinned population. In our latitudes, AK is found in 11-25% of people over 40, whereas in Australia it is around 60%. A study from Hamburg in 2013 was able to show that the overall prevalence was 2.7%, with men more affected at 3.9% than women at 1.5%.

However, the prevalence also increases with age, as studies have shown: In men over 60, 20% are already affected, and in men over 70, as many as 52%. In the last 10 years, a significant increase in AK has also been observed in general. In addition to etiological factors – such as chronic UV exposure – the reason for this is probably demographic change with a higher proportion of older people.

Immunosuppression with drugs, e.g. as a result of organ transplantation, should not remain unmentioned as another significant risk factor: In one study, AK was found in 29% of 452 kidney transplant recipients at the time of the initial examination.

Since squamous cell carcinomas of the skin (PEK) can develop from AK, the question usually arises: with what probability and within what period of time? A 2013 systematic literature review analyzing 24 studies concluded that due to the limited number of available data and methodological limitations, reliable estimates of the incidence of AK development into invasive carcinoma are not currently possible and further studies are needed.

Clinical findings

AK presents especially on UV-exposed skin areas such as capillitium, ear helix, bridge of the nose, forearm extensor sides or back of the hand as skin-colored-reddish or reddish-brownish rough, scaly macules, papules or plaques (Fig. 1). Rarely do individual lesions occur; rather, an entire region is affected. In this context, one speaks of field cankerization.

Diagnostics

Inspection and palpation are appropriate to make the tentative diagnosis of AK. AK, however, is characterized by variable erythema with a variably expressed keratosis. The clinical grading of AK does not correlate with histologic expression. Therefore, the invasiveness cannot be confidently assessed clinically.

In the case of unclear findings, dermoscopy is a suitable procedure for differentiating other diseases and tumors. Numerous studies have demonstrated that AK, pigmented AK, Bowen’s disease, and PEK show typical patterns, especially of the vessels, on dermoscopy: AK show mainly a red pseudonetwork and slightly yellowish-brownish scales, whereas invasive carcinomas show hairpin and irregular vessels, targoid hair follicles, central keratin masses, and ulcerations. AK and PEK can thus also be well differentiated from basal cell carcinomas. In addition, dermoscopy is also useful for differentiating between lentigo maligna, lentigo senilis, and pigmented AK. In addition, the degree of invasiveness correlates with vascular atypia, so dermoscopy can also be used to assess invasiveness. Other non-invasive imaging techniques include confocal laser microscopy and optical coherence tomography, but these are mostly only available to clinics.

If typical clinical findings are present, AK do not require histologic diagnosis. On the other hand, in lesions that are not clinically clear, in which there are signs of progression to PEK, or in which there are no signs of progression to PEK, the patient should be treated. whose biological behavior cannot be assessed, a biopsy should be performed. AK that do not respond to adequate therapy should also be biopsied.

Therapy

A variety of therapeutic options are currently available for the treatment of AK, which does not necessarily facilitate the decision for a particular therapy in everyday practice. Furthermore, the choice for an appropriate treatment depends on patient-, lesion- and therapy-specific factors. Patient factors include age, comorbidities, immunosuppression, comedication, patient wishes and preferences, and treatment adherence. Lesion-related aspects subsume the number of AK, their localization, clinical nature, and the size of the affected field. In addition, as mentioned above, AK is pathogenetically based on DNA damage in the skin, which preprograms recurrences sooner or later.

In principle, each of the existing treatment options is ultimately based on destruction of the affected areas with subsequent re-epithelialization.

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy with liquid nitrogen (-196°C) represents the most common physical destructive treatment procedure of AK in everyday life. Frequency, duration, intensity and specific temperature in the treatment area are not standardized. In the few existing studies, lesion-related healing rates range from 41.9% to 88%, patient-related from 25% to 90.3%, and recurrence rates range from 1.2% to 12% within the first year. Overall, it is more or less an eminence-based method than an evidence-based method, but it is inexpensive, requires little time, and is well tolerated by the patient without local anesthesia. The length of freezing correlates with effectiveness, but also with possible side effects (hypo/hyperpigmentation, scars).

Other ablative procedures, which should only be mentioned here for the sake of completeness, but which have been shown in studies to be at best equivalent to cryotherapy, are surgical procedures (curettage, flat excision, excision, dermabrasion), TCA peeling and laser (ablative, non-ablative).

Photodynamic therapy PDT

PDT is based on selective destruction of skin tumor cells in the epidermis and dermis using a photosensitizing substance (5-aminolevulinic acid ALA, methyl-5-amino-4-oxopentanoate MAL [Metvix®]) and irradiation with high-energy red light. Studies find lesion-related healing rates ranging from 58% to 94.3% and patient-related rates ranging from 31.8% to 91%, with cosmetic outcomes predominantly rated as “excellent” or “good.” However, the time required (3 hours should elapse between application of the cream and irradiation), pain, and stronger local reactions (erythema, edema, pustules, erosions) are perceived as disadvantages.

An ALA-containing patch (Ameluz®, Alacare®) is also available as an alternative to simplify the treatment procedure.

A new variant to conventional PDT is the so-called daylight PDT, which can be performed from the end of April to the end of September. After curettage of crusts and hyperkeratoses and application of sunscreen SPF 20, MAL is applied to the actinic keratoses without occlusion and the patient is instructed to stay outside for 90 to 120 minutes (depending on sun exposure) between 11 am and 4 pm after about half an hour. After that, MAL should be washed off. In the study review, this type of PDT appears to be slightly inferior to equivalent to the conventional method with significantly reduced pain.

Topical 5-fluorouracil (Efudix®)

5-Fluorouracil is a pyrimidine analogue that is incorporated into RNA and DNA as an antimetabolite, inhibiting the synthesis of this nucleic acid. In addition, inhibition of thymidyl synthetase occurs. 5-Fluorouracil 5% should be applied twice daily for 2 to 4 weeks, but other dosage variations are also common, e.g., every 2nd day for 3 weeks to self-treatment by the patient. Usually, there are more or less pronounced inflammatory reactions up to erosions, blisters or necroses, which can ultimately be therapy-limiting. Lesion-related healing rates ranged from 47% to 94%, and patient-related rates ranged from 38% to 96%. Topical low-dose 0.5% fluorouracil in combination with 10% salicylic acid (Actikerall®), applied once daily, usually shows fewer inflammatory skin reactions. Lesion-related healing rate: 39.4% to 98.7%, patient-related: 55.4%.

Imiquimod

Imiquimod is a specific TLR-7 agonist and causes release of a number of cytokines (IFN-alpha, IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-alpha), resulting in an increase in cellular immunity with antiviral and antitumor properties. The 5%-containing cream (Aldara®) is applied three times a week for 4 weeks. According to studies, lesion-related healing rates range from 45.1% to 93.6%, and patient-related healing rates range from 24% to 85%. The 3.75%-containing cream (Zyclara®) is used as interval therapy: 1× daily for 2 weeks, 2 weeks off, 1× daily for 2 weeks, resulting in lesion-related healing rates ranging from 34% to 81.8%.

Diclofenac in hyaluronic acid gel (Solaraze®)

In carcinogenesis, diclofenac as a COX1 and COX2 inhibitor slows proliferation as well as neoangiogenesis and promotes apoptosis. The gel is applied twice daily for 60 to 90 days. In the study overview, lesion-related healing rates range from 51.8% to 81%, and patient-related from 27% to 50%, with adverse reactions (pruritus, erythema, hyp- and paraesthesias, photoallergic reactions) observed significantly less than with imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil.

Ingenol mebutate (Picato®)

The topically applied gel derived from a spurge plant, which induces a breakdown of the mitochondrial membrane potential with consecutive cell necrosis, which clinically manifests itself in a more or less severe toxic dermatitis, was withdrawn from the market in January 2020 due to a possible risk of increased skin carcinogenesis in the treated areas.

Summary

In summary, sun protection, especially at a young age and in cases of chronic UV exposure, is the most important measure in the primary prevention of AK. However, once sun damage is set and “burned” into the skin’s genome, early detection and treatment becomes a top priority. A variety of therapeutic options and modalities are available in the treatment of AK. Each method has certain advantages, but also disadvantages. The study review shows that the effectiveness of the treatment options presented ranged from 50% to 90%, with PDT performing slightly better than Solaraze®, which also reflects clinical experience. The aim should be to adapt the treatment regime to the individual patient, switching between individual procedures over time or combining methods. In addition, not every patient responds equally well to a particular treatment method. Occasionally, more pronounced local inflammatory side-effect reactions occur during treatment, whereas in other patients it seems that nothing happens at first, but the AK lesions nevertheless eventually heal completely. In this respect, the educational discussion and the guidance of the patient have very decisive functions. On the one hand, the patient must be informed about the chronic light damage to the skin, the onset of carcinogenesis and the regular control examinations that will therefore probably be necessary throughout life, and on the other hand, he/she must be informed about the various therapeutic options. However, this requires that the treating dermatologist is familiar with “playing the keyboard” of AK treatment options.

Take-Home Messages

- Sun protection, especially at a young age, is the most important primary prevention measure against AK in the case of chronic UV exposure.

- AK are a marker of chronic sun damage and skin carcinogenesis.

- Early treatment of AK is indicated.

- A variety of AK treatment options are available.

- Education and an individual treatment concept are fundamental principles in AK therapy.

Literature:

- S3-Guideline Actinic keratosis and squamous cell carcinoma of the skin, AWMF-Guideline of the German Dermatological Society March 2020.

- Kornek T, Augustin M: Skin cancer prevention. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2013; 11(4): 283-296.

- Green AC: Epidemiology of actinic keratoses. Curr Probl Dermatol 2015; 46: 1-7.

- Memon AA, et al: Prevalence of solardamage and actinic keratosis in a Merseyside population. Br J Dermatol 2000 ; 142(6): 1154-1159.

- Schmitt J, et al: Occupational ultraviolet light exposure increases the risk for the development of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol 2011; 164(2): 291-307.

- Werner RN, et al: The natural history of actinic keratosis: a systematic review. Br J Dermatol 2013; 169(3): 502-518.

- Huerta-Brogeras M, et al: Validation of dermoscopy as a real-time noninvasive diagnostic imaging techniquefor actinic keratosis. Arch Dermatol 2012 ; 148(10): 1159-1164.

- Zalaudek I, et al: Dermatoscopy of facial actinic keratosis, intraepidermal carcinoma and invasive squamous cell carcinoma: A progression model. J Am Acad Dermatol 2011.

- Akay BN, et al: Dermatoscopy of flat pigmented facial lesions: diagnostic challenge between pigmented actinic keratosis and lentigo maligna. Br J Dermatol 2010; 163(6): 1212-1217.

- Lallas A, et al: The clinical and dermoscopic features of invasive cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma depend on the histopathological grade of differentiation. Br J Dermatol 2015; 172(5): 1308-1315.

DERMATOLOGY PRACTICE 2020; 30(4): 6-9