The proportion of HPV-vaccinated 18-24-year-old women has stagnated at about 50%. Vaccination coverage must be significantly improved if the circulation of papilloma virus is to be sustainably reduced. One possibility, for example, is the planned vaccination of adolescent boys and young men. The adolescent window of the two-dose HPV vaccine schedule ends at the 15th birthday. After this youth window, three doses are required instead of two. Despite this, nearly two-thirds of all HPVVaccinations given at age after 15th birthday, which reduces efficacy (one-third already had sexual intercourse at time of vaccination). Furthermore, the risk of temporal coincidence with rare autoimmune diseases increases with age.

The development of HPV vaccination and HPV detection methods has been shaped by the HPV research work of Harald zur Hausen, for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2008. Two HPV vaccines are licensed in Switzerland that provide high protection against two (bi-valent, bHPV, 2vHPV) or four HPV types (quadri-valent, qHPV, 4vHPV). The market launch of an HPV vaccine immunizing against nine HPV types is planned for next year (2016) (novem-valent, 9vHPV). Both the 4vHPV and the 9vHPV are 90% protective against the pointed condylomas >. The 9vHPV covers additional oncogenic HPV types (so-called “high risk” types), although their frequency varies internationally [1]: Thus, the oncogenic types 51 (in fourth place) and 59, which are relatively frequent in Switzerland, are not included in the 9vHPV. In addition, side effects at the injection site (burning/pain, erythema, swelling) are reported to be even more frequent with 91% (9vHPV) vs. 85% (4vHPV) [2] – the vaccinating MPAs and physicians will have to intensify their educational work accordingly.

The novem-va^lente HPV vaccine will only be able to demonstrate its theoretically possible contribution of a maximum additional 20% reduction in cervical carcinomas if it were to replace the bi- and quadrivalent HPV vaccines entirely and the vaccination coverage were to increase markedly.

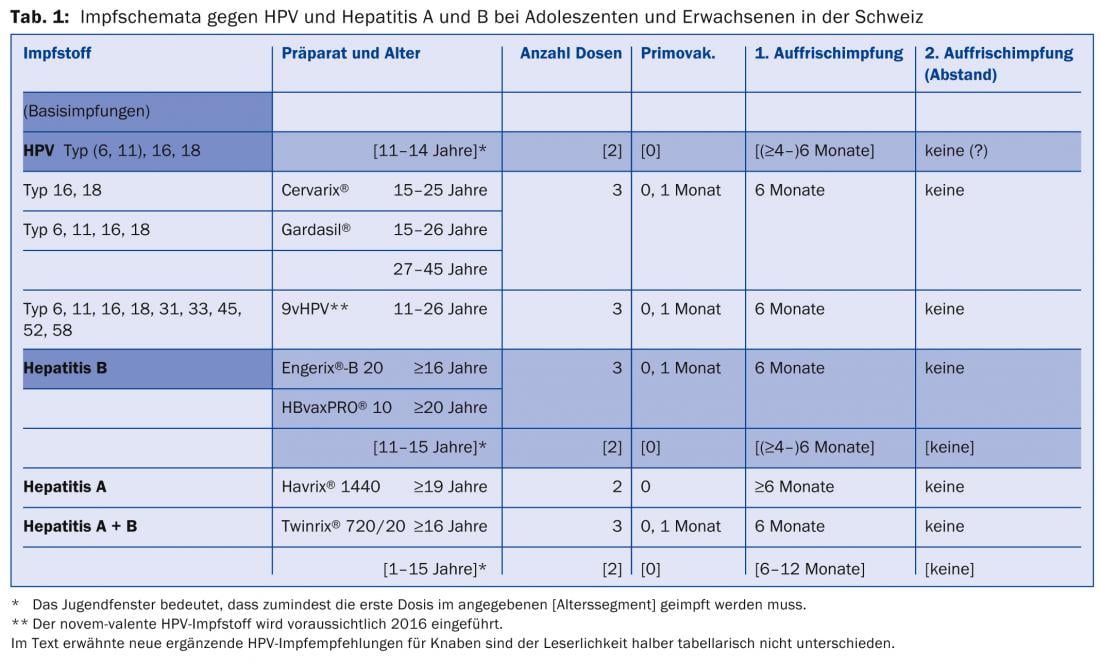

Vaccination schemes

A two-dose vaccination schedule is in place in Switzerland for HPV vaccinations, with the start of this so-called two-dose adolescent window from age 11 until the 15th birthday (latest date of first dose; recommended since February 2012). Similarly, two-dose regimens have existed since Oct. 2000 in the youth window for hepatitis B vaccination between the 11th and 16th birthdays, and since August 2001 for combined hepatitis A+B vaccination between the 1st and 16th birthdays. It is obvious and immunologically possible to treat against HPV and hepatitis (A and) B simultaneously in two sessions six months apart in the adolescent window 11-15. In each case, one injection was administered into the left and right m. deltoideus (Table 1).

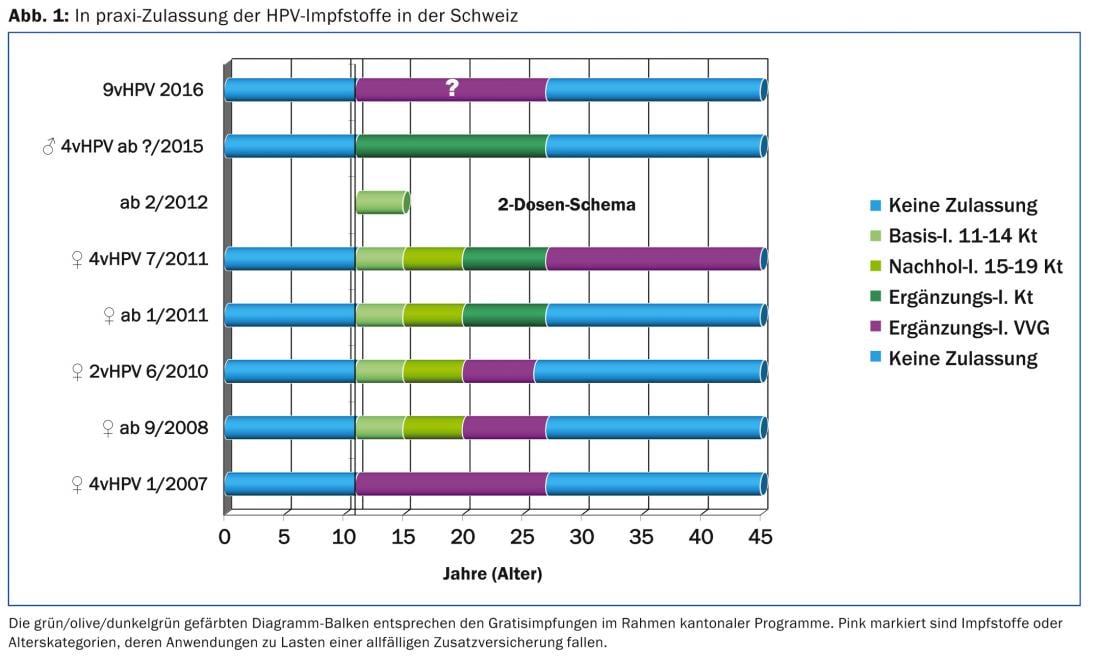

In cantonal programs, the possibility of “free vaccination” of young women born 1984-2003 has existed since September 2008 (Fig. 1). An evaluation of HPV vaccination commissioned by the Federal Office of Public Health [3] showed vaccination coverage rates of 18-24 year-olds of a good 50%. This is judged to be insufficient to reduce viral circulation of oncogenic HPV types 16 and 18 and also to protect non-immunized individuals (so-called herd effect). Since the infection status of the current partner is the most important risk factor for HPV transmission, the supplementary HPV vaccination of adolescent boys and young men planned this year, also within the framework of cantonal programs, is not only a corrected “access equity” [4] but also a possible protection against viral transmission. A Canadian study [5] demonstrated that HPV prevalence was higher in individuals with infected partners (85%) than in patients whose partners were HPV negative (19%). Condoms exerted a stronger protective effect in men than in women. In a US observational epidemiologic study, HPV prevalence was 38% (HPV testing eight months after cohabitating) despite consistent condom use [6]. Of course, the same two-dose schedule exists for boys in the adolescent window, which is the optimal time to vaccinate. In theory, the only distinction made in the 2015 Swiss vaccination recommendations is that HPV vaccinations in adolescent boys are not referred to as basic or catch-up vaccinations as in girls, but as “supplementary vaccinations.” For supplementary vaccinations, there are no requirements to achieve a minimum vaccination coverage rate with the help of appropriate campaigns.

Impact of HPV vaccination and research on cervical cancer screening.

The bi- and quadrivalent vaccines can theoretically prevent up to 70% of cervical cancers when vaccinated before cohabitating; the novem-valent HPV vaccine can prevent up to 90% [2]. Since this primary prevention of cervical cancer does not provide complete protection, secondary prevention measures (cervical smears) must be continued. Among vaccinated women under 25 years of age, one-quarter (25.2%) reported that they were still recommended cancer smear, but that it was needed less frequently [3]. Although this change in screening behavior is not without controversy, it is important to consider that the sensitivity of the single Pap smear (50-70%) may decrease in cohorts of young women with high vaccination coverage. Severe cervical dysplasia (so-called HSIL, High-grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion) is diagnosed by cytotechnologists in approximately 0.2% of all cervical smears; a decrease in the positive-pathologic proportion could result in fewer positive cytologies being detected. Maximal vaccination coverage can theoretically reduce HSIL changes by 50% (2vHPV and 4vHPV) to 80% (9vHPV) [2], meaning that a single positive HSIL Pap smear can still be detected for every 1000 submissions.

In addition, cervical screening in Switzerland must adapt to international recommendations. Preferably recommended (US cancer/colposcopy/pathology societies: ACS, ASCCP, ASCP) is cervical co-testing at 5-year intervals from age 30-65 years. Co-testing means that from the same cervical smear (“liquid based” LBC) the cytological (microscopic Pap test) and the molecular biological (fully automated HPV test) result are obtained. To avoid confounding one in ten women by co-testing (positive HPV DNA tests due to e.g. transient HPV infections, test specificity 90%), preference should probably be given to HPV mRNA tests with a specificity towards 95% [7]. HPV testing and HPV vaccination are main topics of the biennial international EUROGIN congresses. The practicing author succeeded in convincing his foreign laboratory, thanks to congress information and his own publication [8], to include this so-called Aptima® HPV mRNA test in the analysis program in Switzerland for the first time (Fig. 2).

Papillomavirus mRNA group genome detection is charged to line item 3133.00 (CHF 54). In the USA, the Aptima® HPV mRNA assay was approved by the FDA in October 2011 (FDA approved). This assay specifically detects the oncogenic proteins E6/E7 of 14 high-risk HPV types (16, 18, 31, 33, 35, 45, 51, 56, 58, 59, 66, 68) that are overexpressed as a result of infection persistence – based on ribosomal translation of HPV mRNA. This cellular deregulation is the result of the integration of the viral genome into the nuclei of the basal cervical epithelium. The possible shifts within the different (“high risk”) HPV type prevalences due to vaccination argue for a high-risk HPV mRNA test with broad type coverage, i.e. including types 51 and 59, which are not included in the 9vHPV vaccine and are relatively common in Switzerland.

Take-Home Messages

- Basic and catch-up vaccination coverage rates (11-19-year-old adolescent girls) against human papilloma virus (HPV) should have been optimized since 2011 with cantonal supplementary vaccination programs for 20-26-year-old women. Despite this, the proportion of vaccinated 18-24 year old women has stagnated at around 50% [3].

- In order to sustainably reduce the circulation of papilloma virus and thereby achieve a herd effect, higher vaccination coverage, e.g., via planned vaccination of adolescent boys and young men, must be achieved.

- Although gynecologists are the most common HPV vaccinators, accounting for 32% of all HPV vaccinations (primarily catch-up and supplemental vaccinations [3]), and are following up on this new core competency, it is important to remember that HPV vaccination is primarily intended as a Basic vaccination of 11-14 year olds is recommended and would therefore fall in 99.5% before the time of the first sexual intercourse or at the same time.

- The fact that almost two-thirds of all HPV vaccinations are given after the age of 15 reduces efficacy on the one hand (one-third of late adolescents had already had sexual intercourse at the time of vaccination), and on the other hand, with increasing age, carries the risk of temporal coincidence with rare autoimmune diseases such as multiple sclerosis or neurological diseases (Guillain-Barré syndrome) [9]. In addition, the HPV vaccination schedule after the adolescent window (starting on the 15th birthday) requires three doses instead of two.

Daniel Brügger, MD

Literature:

- Krech T, et al: Genitourinary human papillomavirus and chlamydia. Schweiz Med Forum 2010; 10(12): 230-232.

- Luxembourg A (CDC/NCIRD): 9-valent HPV (9vHPV) Vaccine Program Key Results. www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2014-10/HPV-02-Luxembourg.pdf

- Mice number-Feuz M: Evaluation of HPV vaccination. VIII. Vaccination Congress, 06.11.2014 Biel.

- Stronski-Huwiler S: HPV vaccination in Switzerland: Girls AND Boys? VIII. Vaccination Congress, 06.11.2014 Biel

- Burchell AN, et al: Influence of Partner’s Infection Status on Prevalent Human Papillomavirus Among Persons With a New Sex Partner. Sex Transm Dis 2010; 37(1): 34-40.

- Winer RL, et al: Condom use and the risk of genital human papillomavirus infection in young women. N Engl J Med 2006; 354(25): 2645-2654.

- Monsonego J, et al: Evaluation of oncogenic human papillomavirus RNA and DNA tests with liquid-based cytology in primary cervical cancer screening: the FASE study. Int J Cancer 2011; 129(3): 691-701.

- Brügger D: What will become of gynecologic cancer screening? Gynecology 2010; 5: 6-8.

- Siegrist CA: Autoimmune diseases after adolescent or adult immunization: What should we expect? CMAJ 2007; 177(11): 1352-1354.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(2): 17-20