Dermatosurgery deals with the surgical treatment of mainly malignant, but also benign skin neoplasms. While skin neoplasms were previously often treated by radiotherapy, cryotherapy and electrocautery, new surgical techniques and plastic reconstructive procedures have eclipsed physical forms of treatment. The continued increase in the incidence of skin cancer clearly reflects the importance of dermatosurgery. Surgical procedures with complete histologic incision margin control continue to be perfected, also with the goal of safe minimally invasive removal of the skin tumor. Resulting large defects can be closed with a good cosmetic result thanks to plastic techniques. Apart from further developments in the field of surgical techniques, there have also been some changes in the perioperative area.

If excision of a skin tumor is being considered, written documentation of the reason, purpose, and type and modality of treatment, including potential complications and risks, should be performed and patient consent obtained prior to the procedure. It is also important to point out possible consequences if the patient refuses treatment. It should be noted that the reconnaissance at least. Should be performed 24 hours prior to the procedure to allow the patient sufficient time to think about it.

Perioperative management of anticoagulants

One of the most important recent changes has been in the management of existing anticoagulation. Whereas anticoagulation used to be paused or switched to low-molecular-weight heparin before dermatosurgical procedures, a paradigm shift has emerged in recent years. Even with major flap surgery, it is now recommended that the use of acetylsalicylic acid, clopidogrel, prasugrel, ticagrelor, or phenprocoumon not be paused or switched [1,2]. This is due to study data showing that there is a risk of thromboembolic complications when anticoagulation is paused or switched. The data also demonstrate that the risk of postoperative rebleeding is indeed increased with continued anticoagulation, but the morbidity of these complications weights much lower compared with thromboembolic events.

If platelet aggregation inhibition is taken as primary prophylaxis, it can be paused ten days before surgery in consultation with the general practitioner and restarted three days later. In case of oral anticoagulation with Marcoumar®, the preoperative INR should be ≤3.5. Depending on the urgency of the planned surgery, the benefit of surgery must be weighed against the increased risk of hemorrhage if the INR is >3.5 [2]. The data situation for the newer anticoagulants (rivaroxaban, dabigatran, apixaban, fondaparin) is still insufficient, which is why reliable recommendations are lacking. The German S3 guideline recommends pausing these preparations at least 24 hours before surgery, whereas American publications do not consider pausing necessary [1].

Regardless of anticoagulation, it is fundamentally essential to perform precise hemostasis using electrocautery during surgery with regard to postoperative bleeding. Especially vessels from the depth of the wound must be coagulated or ligated. Bleeding from the wound edge is usually prevented by good skin adaptation during closure. In addition, a pressure dressing should be applied postoperatively for 48 hours to minimize the risk of hematoma or rebleeding. However, for operations in the facial region (with or without anticoagulation), especially periorbital, it is important to inform the patient preoperatively about the high probability of sometimes extensive suffusions. Although cosmetically disfiguring, these hematomas regress spontaneously after a few days and do not require therapy.

Antibiotic prophylaxis

The worldwide increase in antibiotic resistance in medicine and the results of numerous studies led to the reconsideration and adaptation of prophylactic use to prevent endocarditis or joint prosthesis infection or wound infection. Consecutively, the recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis in dermatosurgical procedures were also adapted.

The infection rate in dermatosurgical operations is generally very low and is reported in the literature to be 0.4-4% [3,4]. Very low infection rates are also found in two-stage surgery (Mohs surgery). Even when non-sterile gloves were used during primary excision in Mohs surgery, no more infections occurred compared to incision margin-controlled procedures with sterile gloves [5].

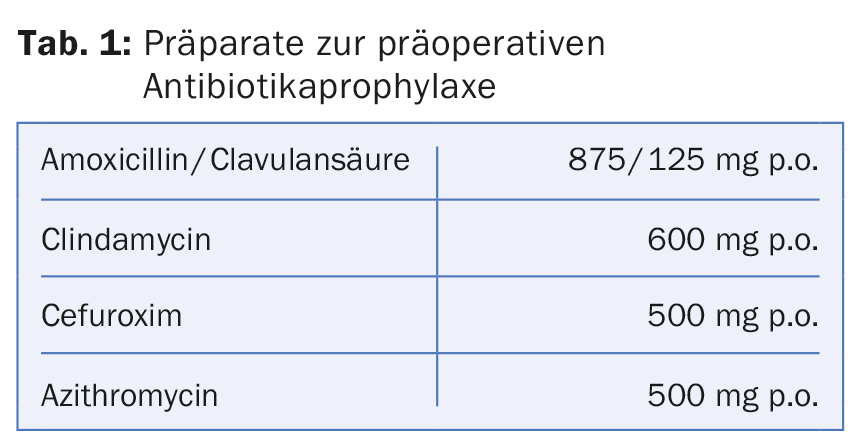

Regardless of the low infection rates, antibiotic prophylaxis is still used too frequently in dermatosurgery, as evidenced by several previous studies [6]. Based on this evidence, the indication for antibiotic prophylaxis should henceforth be very restrictive. General antibiotic prophylaxis is not recommended for procedures on nonsuperinfected skin because of the low rate of wound infections, bacterial endocarditis, and prosthetic joint infections. Only in cases of high risk of wound infection and procedures on the mucosa or infected skin is preoperative antibiotic administration advised. This should be given as a single peroral dose 30-60 minutes before surgery to ensure that the antibiotic is contained in the blood-fibrin cogel in the wound area. Table 1 lists possible preparations for preoperative prophylaxis.

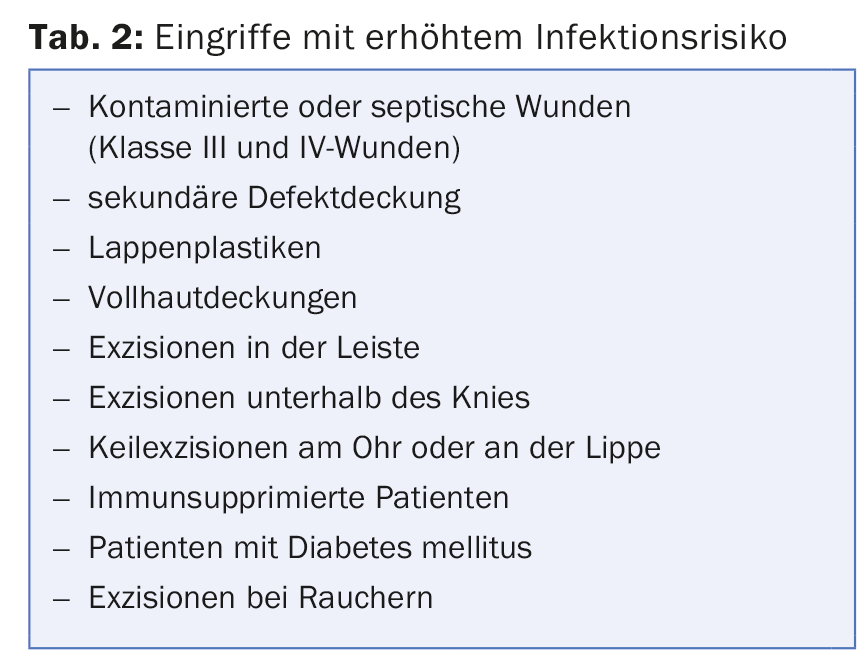

Postoperative infections usually manifest on the second postoperative day. A follow-up check performed at this time allows early detection of infection, and the first dressing change can be performed at the same time. Particularly in the case of high-risk patients and operations in special regions, follow-up monitoring is advisable because of the increased risk of infection (Tab. 2).

Prophylactic postoperative administration of antibiotics contradicts current recommendations and should only be prescribed in cases of manifest wound infection [6].

Skin disinfection

For antiseptic treatment of the surgical site, alcohol-based preparations or PVP-iodine solutions are mainly available. The former require a shorter exposure time compared to the PVP-iodine solutions.

The choice of disinfectant depends on the surgical region. In the face, especially near the eyes, a disinfectant containing alcohol should be avoided and used instead, e.g. Octenisept®. For the hairy seborrheic head area, on the other hand, it is recommended to use a colorless alcohol-based disinfectant. On the rest of the body, for example, Betaseptic® is recommended, which has a very broad action against microorganisms. One of the advantages of Betaseptic® is that the brown color of the solution indicates whether the entire surgical area has been disinfected. This can be advantageous, for example, during operations on the ear.

Before covering the surgical site with sterile draping material, the disinfectant must have dried, especially if alcohol-based disinfectants are used. On the one hand, there is better adhesion of the masking material, on the other hand, there is the risk that the alcohol can ignite when using the electrocautery.

Shaving the hair is recommended right before surgery because shaving before the day of surgery increases the rate of infection. The use of disposable razors usually results in small skin injuries with a consecutive increased risk of wound infection, which is why the use of a hair trimmer is recommended.

Local anesthesia

In the vast majority of cases, lidocaine 1% is used for local anesthesia, usually in combination with epinephrine as a vasoconstrictor. The duration of action of lidocaine is approximately 30-120 minutes. Longer acting is bupivacaine, which is a useful alternative, e.g., for procedures on toes or fingers, to minimize immediate postoperative pain.

The injection should first be administered subcutaneously. On the one hand, the burning pain is felt less strongly in the subcutis than in the dermis due to the local anesthetic, and on the other hand, slight hydrodissection occurs as a result of the injection, which facilitates subsequent blunt preparation in the displacement layer. In addition, lifting the skin creates a greater safe distance from the deeper vascular and nerve structures. After placing a subcutaneous depot, the needle can be withdrawn and subsequently another depot can be injected intradermally. This allows for very fast anesthesia.

To reduce pain from the local anesthetic, sodium bicarbonate (NaBic) can be added in a 1:4 ratio when lidocaine is used. This is not possible with bupivacaine; a precipitation reaction would occur with the addition of NaBic.

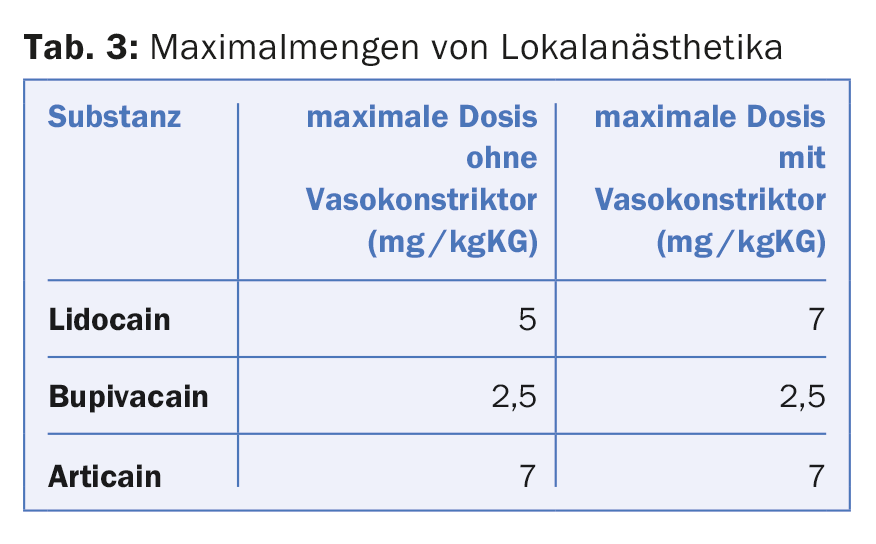

In the case of large dermatosurgical procedures using local anesthesia, the maximum quantities of anesthetics must be observed due to cardiotoxic complications (Tab. 3). To anesthetize large areas of skin, the local anesthetic can be diluted with NaCl in the same way as the tumescent solution in order not to exceed the maximum amounts.

Incision margin control, micrographically controlled surgery

Especially in the face, simple wound closure with side-to-side adaptation is often not possible with large tumors due to the resulting high skin tension. In this case, special surgical techniques in terms of flap plasty are necessary. Because skin is displaced or rotated during such procedures, prior histologically confirmed totality of excision is essential. Mohs surgery is considered the safest excision method here. If histological examination of the excised tissue is not possible on the same day, definitive wound closure can also be performed several days after excision. Epigard® is recommended for temporary defect coverage.

Flap Plastics

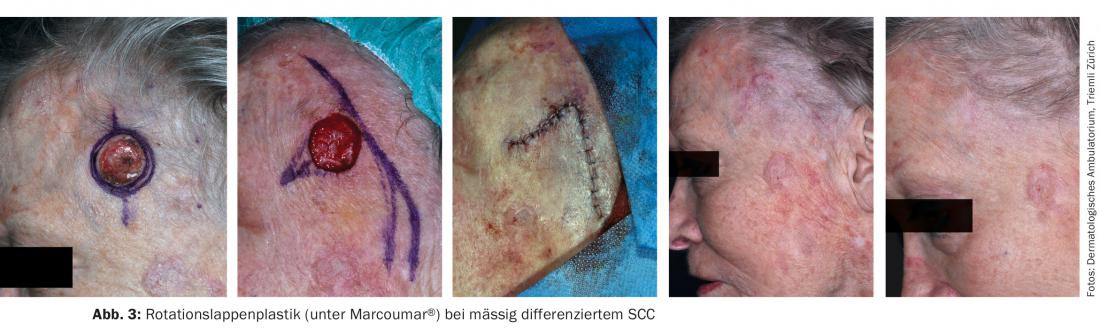

There are different types of flapplasties (displacement, rotation and transposition flapplasties, Fig. 1-3). There are often several options for covering the excision defect. As a rule of thumb, a simple closure technique should be preferred over heroic flap surgery. The possibility of placing the scar in the facial mimic folds must be weighed. In order to be able to mobilize sufficient skin, it should be determined where the best skin displacement or the largest “skin reservoir” is available in order to achieve the most tension-free skin closure possible.

In very large tumors, defect coverage can be achieved using split or full thickness skin (Fig. 4) , although the cosmetic result is usually inferior to flap surgery.

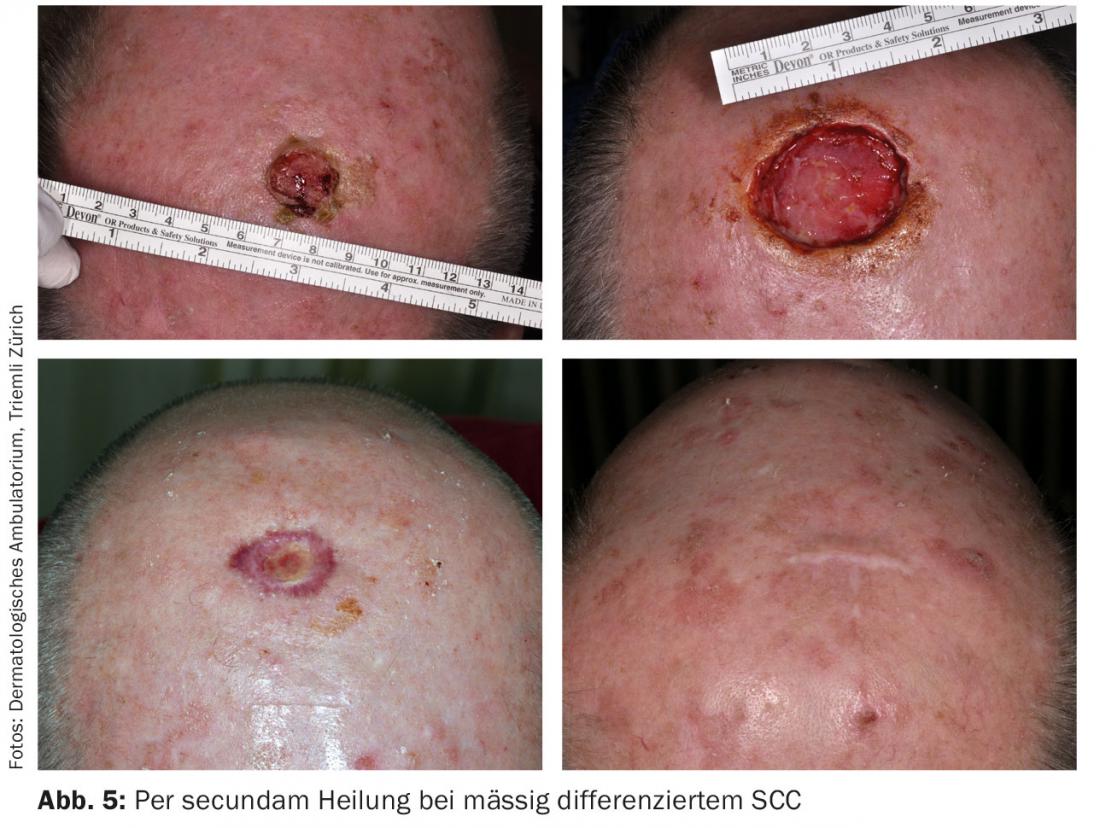

Apart from these special closure procedures using flap plasty, one should also evaluate the possibility of per secundam healing. Often, a cosmetically satisfactory result can be achieved, although the healing time is prolonged compared to primary wound closure. Concave areas of the face in particular, such as the temporal region, the nasolabial fold and the medial corner of the eye, are ideal for this purpose. Even with operations in convex regions, the cosmetic result is often astonishing (Fig. 5) . In order to reduce the size of the primary defect, a so-called tobacco pouch suture can be performed if secondary healing is planned. However, studies in this regard do not document a better cosmetic result and only a statistical trend for a reduction in healing time [7].

Postoperative procedure

After wound closure, a sterile compression bandage should be applied to prevent secondary bleeding. In the scalp area, this occasionally requires a “turban bandage” for fixation so that sufficient pressure can be applied to the wound bed. This should be left for two days and kept dry. Subsequently, it can be replaced by a smaller bandage. Opsite® plasters, which adhere very well and are water-repellent, have proved very successful as postoperative wound dressings.

According to the literature, the application of local antibiotic ointments to the fresh suture has no effect on the infection rate. In addition, with regard to postoperative management, the results of the Cochrane Reviews are interesting. According to these data, the type of wound dressing used does not matter in terms of infection rate. There is also no evidence that early dressing changes or early bathing/showering promotes the occurrence of infections [8–10]. However, the validity of some of the reviews is limited given the studies included.

If suture removal is necessary due to the use of non-absorbable suture material, it should be performed on the face after five to seven days and on the trunk, extremities and scalp after 10-14 days.

Literature:

- Brown DG, Wilkerson EC, Love WE: A review of traditional and novel oral anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy for dermatologists and dermatologic surgeons. J Am Acad Dermatol 2015 Mar; 72(3): 524-534.

- Palamaras I, Semkova K: Perioperative management of and recommendations for antithrombotic medications in dermatological surgery. Br J Dermatol 2015 Mar; 172(3): 597-605.

- Napp M, et al: [Significance and prevention of post-operative wound complications]. Dermatologist 2014 Jan; 65(1): 26-31.

- Saco M, et al: Topical antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of surgical wound infections from dermatologic procedures: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat 2015 Apr; 26(2): 151-158.

- Mehta D, et al: Comparison of the prevalence of surgical site infection with use of sterile versus nonsterile gloves for resection and reconstruction during Mohs surgery. Dermatol Surg 2014 Mar; 40(3): 234-239.

- Bae-Harboe YS, Liang CA: Perioperative antibiotic use of dermatologic surgeons in 2012. Dermatol Surg 2013 Nov; 39(11): 1592-1601.

- Joo J, et al: Purse-string suture vs second intention healing: results of a randomised, blind clinical trial: JAMA Dermatol 2015 Mar; 151(3): 265-270.

- Toon CD, et al: Early versus delayed post-operative bathing or showering to prevent wound complications. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 7: CD010075.

- Toon CD, et al: Early versus delayed dressing removal after primary closure of clean and clean-contaminated surgical wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2015; 9: CD010259.

- Dumville JC, et al: Dressings for the prevention of surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014; 9: CD003091.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2016; 26(1): 24-28