After an injury, expectations regarding a return to sport should be clarified from the beginning and clear goals should be set. Phase-adapted rehabilitation takes place as a team. The decision as to when a patient can return to sport must be determined on an individual basis according to clear criteria. Functional tests help to objectify these decisions. Biology, physiology, and psychology must be restored before the patient returns to sports.

When will I be able to do my sport again? This is often one of the first questions patients ask the attending physician after injuries. The question can hardly be answered in a general way, as it depends on various factors when a patient is “fit” to play sports again. Ideally, there should be a systematic decision-making process with clear criteria. As a physician, one is often caught between the coach, therapist, and athlete [1]. The end point is to reach the level of sport before the injury. The time frame required for this depends on the type of sport and the intensity. As an example, the replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament can be used to explain the return to sport, as this is one of the most common sports traumatology operations and is therefore extensively researched.

Who will make it back to the sport?

In a recent meta-analysis of approximately 7500 patients, it was shown that eight out of ten patients make it back to sports after cruciate ligament replacement [2]. However, only 65% reach the level they had before surgery, and just over half return to competitive sports. From the data, an ideal patient for a successful return to sports after anterior cruciate ligament replacement surgery can be derived: The patient is young (OR 1.4) and elite athlete (OR 2.5 for the level he had before the accident, 6.0 for competitive sports), was fitted with a hamstring graft (OR 2.4 for competitive sports), has a normal IKDC score for documentation of knee injury (OR 1.9) and side matched functional tests at follow-up, furthermore he has a positive attitude and is anxiety free [2].

Phase-adapted gradual rehabilitation

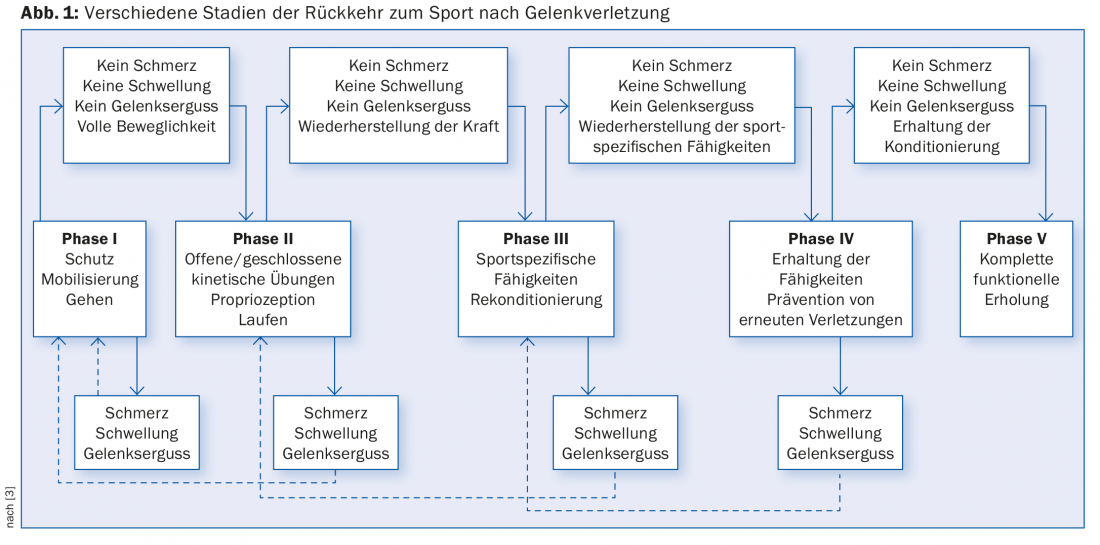

Rehabilitation after an injury usually takes place in an interdisciplinary team of physiotherapists, doctors and trainers and, if necessary, sports psychologists. The goal is functional recovery, taking into account biology, metabolism, and neuromuscular deficits and considering psychosociological aspects [3]. Soft tissue healing occurs in phases – rehabilitation should therefore be structured in an adapted manner (Fig. 1) .

In this context, it is difficult to make evidence-based recommendations because the phases overlap and also vary intraindividually. It makes more sense to agree on goals and proceed step by step, adapted to the patient’s individual possibilities. Low-knee-impact sports activities such as aqua jogging or cycling (on an ergometer) can be incorporated into therapy. For return to sports, the biological processes of healing should be sufficiently advanced, physiological functions restored, and mental readiness intact.

Biological factors

On the one hand, the biological factors are intrinsic, i.e. the ideal patient is a non-smoker who is as healthy, athletic and motivated as possible. After replacement of the anterior cruciate ligament, extrinsic factors include the type of sport and its intensity, but also the surgical procedure chosen with appropriate anatomical reconstruction, graft selection and stable fixation, and thus the surgeon’s experience. Other decisive influences are concomitant injuries to ligaments, menisci or cartilage. Once the conditions for a return to sport are met for these factors, the way is clear for the healing phases to proceed normally after a ligament injury.

After the initial inflammatory phase lasting a few days, revascularization takes place during ten days to six weeks. Remodeling of the scar takes another six weeks, and after about four months the new collagen has matured and structurally adapted to the stresses. In cruciate ligament replacement, this phase is followed by the so-called ligamentization, which describes the structural remodeling of the graft. Histological and magnetic resonance imaging can demonstrate remodeling processes in the graft for up to two years [4]. The shortest healing time is four months with conservative therapy and six months after cruciate ligament replacement [5].

Aspects of physiology

The injury to the anterior cruciate ligament results in at least a partial loss of proprioception. Loss of the reflex arc limits sensory function. The coordination of the musculature must be learned again after the injury and be centrally geared, and like all learning, the speed here depends on the number of repetitions and is therefore time-consuming and varies from individual to individual. Early, active practice is important, so it makes sense for the patient to receive physical therapy support as soon as possible after the injury.

Often, certain instabilities of the leg axes already exist before the injury as a result of strength imbalances and deficits, which are also blamed for the injury, among other things. For proper function is responsible for the whole axis – trunk muscles, especially the hip muscles, and the entire leg muscles. The goal is to avoid a functional valgus position. There are also postoperative strength deficits, always affecting the quadriceps femoris muscle (motor of the knee); this should be trained again (at least isometrically) as early as possible [6].

Psychological aspects

Psychosocial factors are responsible for up to 50% of patients who do not return to sports [7]. In addition to the physical stress, there is also the psychological stress with limitations of self-confidence and fear. Fear of re-injury is normal, but it should not lead to avoidance behavior, but should be overcome. It makes sense to clarify expectations and set realistic goals, including any interim goals, at the beginning of therapy. Preoperative physical therapy already helps the patient mentally adjust to the road ahead and correlates with a good outcome. It is important to support and maintain the athlete’s motivation. Close and good supervision by a motivated physiotherapist is probably the most important support.

The goal: functional stability

Whether functional stability can be achieved depends, among other things, on the main sport and the corresponding load components. The static prerequisite is the restored stability of the knee joint in anterioposterior translation and especially also rotation. The amount of training plays an essential role in compensating for muscular deficits and imbalances. In this context, neuromuscular influencing factors such as proprioception and muscle reaction time are decisive for the function of the affected joint.

Important psychological factors besides the athlete’s motivation are compliance and self-efficacy.

Assessment of sports ability

At the beginning of the assessment is a conversation: What is the requirement, where do you stand, how do the physiotherapist and trainer see it? Scoring systems such as Lysholm, IKDC, Tegner, KOOS or ACL-QoL etc. have been established for subjective assessment [8]. A complete clinical examination of the joint, also to exclude any new concomitant lesions, is mandatory. In addition to the trophic assessment, the range of motion is also documented in a side-by-side comparison. Objective stability – at least anterior tibial translation – can be measured using anterior drawer and Lachmann test and quantified with instruments such as the Rolimeter or KT 1000. For the objectification of rotational stability, the pivot shift test standard, which is not always easy to assess, exists in clinical practice. Isokinetic force measurements (Cybex test) give a good overview of any differences in force between injured and healthy extremity and show dysbalances between flexors and extensors.

Various functional tests have been established to test the function (Fig. 2) . These essentially consist of balance exercises and various jump tests. Usually, the patient is then cross-compared with a comparison collective, but longitudinal measurements would be more ideal. These tests are time-consuming and have therefore so far been used almost exclusively in competitive sports. Using a new, simplified test set-up, we are currently testing all cruciate ligament injured patients at the Cantonal Hospital Aarau prior to return to sports [9]. The goal is to record and target specific deficits, thereby reducing the re-injury rate.

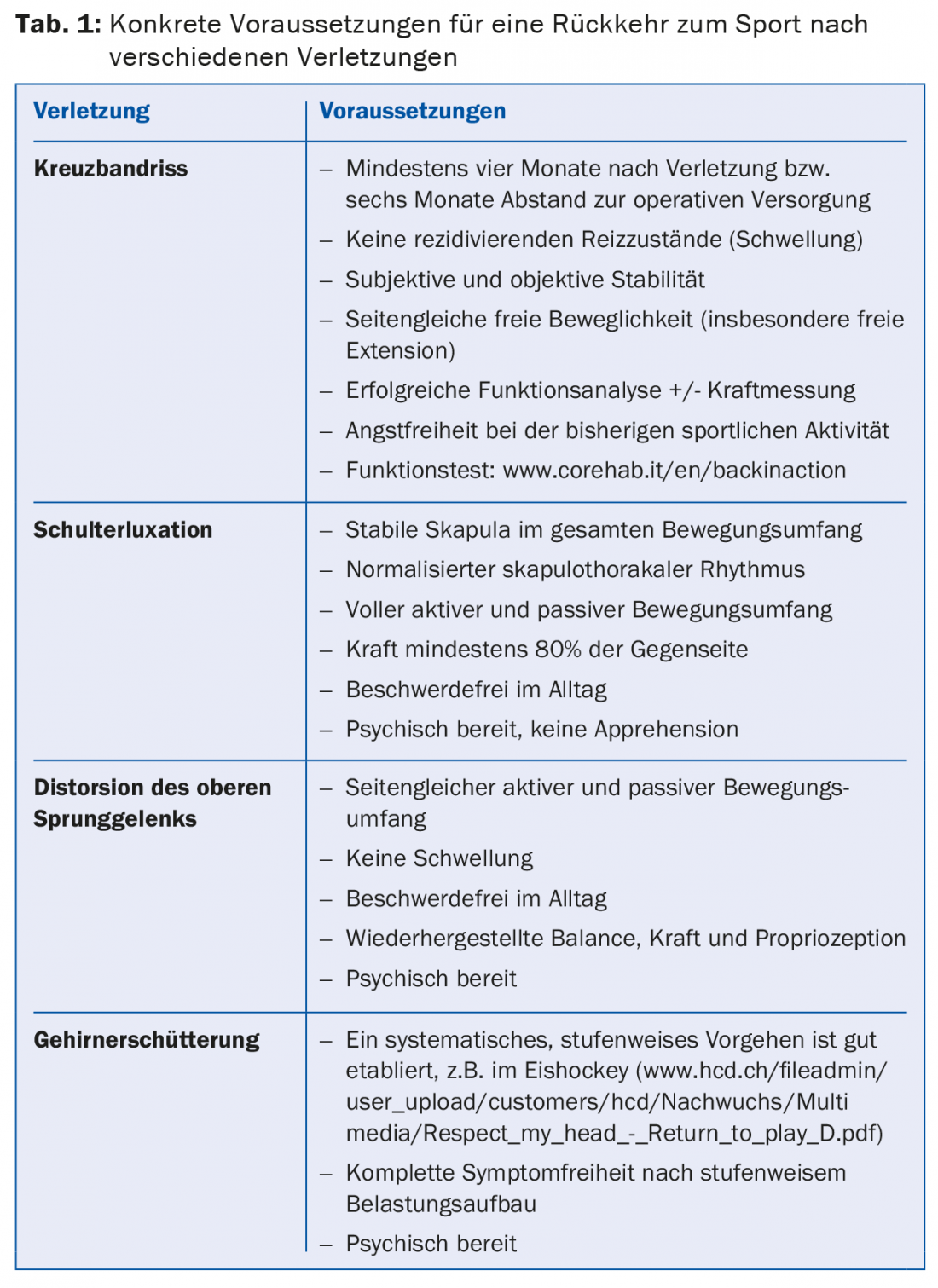

An overview of the specific requirements for a return to sport after various injuries is given in Table 1.

Injury prevention

When returning to sports, preventive thinking should always be taken into account. After cruciate ligament reconstructions, up to 10% of patients suffer re-ruptures, and ruptures of the opposite side occur in up to 23%. Therefore, physiotherapy should always be symmetrical to compensate for pre-existing neuromuscular deficits. However, not only functional training is important, but also muscle building, flexibility and endurance. Postural stability, i.e. the perception of the body in space, plays an essential role in injury prevention. Established training programs such as FIFA 11+ (http://f-marc.com/11plus/home) [10] are recommended.

Literature:

- Shrier I, et al: Return to play following injury: whose decision should it be? Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(5): 394-401.

- Ardern CL, et al: Fifty-five per cent return to competitive sport following anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction surgery: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis including aspects of physical functioning and contextual factors. Br J Sports Med 2014; 48(21): 1543-1552.

- Roi GS, et al: Return to competition following athletic injury: sports rehabilitation as a whole. Apunts Med Esport 2010; 45: 181-184.

- Moshiri A, Oryan A: Tendon and Ligament Tissue Engineering, Healing and Regenerative Medicine. J Sports Med Doping Stud 2013; 3: 126.

- Petersen W, Zantop T: Return to play following ACL reconstruction: survey among experienced arthroscopic surgeons (AGA instructors). Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013; 133(7): 969-977.

- Petersen W, et al: Return to play following ACL reconstruction: a systematic review about strength deficits. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2014; 134(10): 1417-1428.

- Ardern CL, et al: A systematic review of the psychological factors associated with returning to sport following injury. Br J Sports Med 2013; 47(17): 1120-1126.

- Rodriguez-Merchan EC: Knee instruments and rating scales designed to measure outcomes. J Orthop Traumatol 2012; 13(1): 1-6.

- Herbst E, et al: Functional assessments for decision-making regarding return to sports following ACL reconstruction. Part II: clinical application of a new test battery. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2015; 23(5): 1283-1291.

- Barengo NC, et al: Impact of the FIFA 11+ training program on injury prevention in football players: a systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2014; 11(11): 11986-12000.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(8): 20-23