Rectal prolapse is a symptom of pelvic floor insufficiency. It can be recognized by the circular folding, in which it differs from anal prolapse. Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy according to D’Hoore is the favored form of therapy.

82-year-old Mrs. H. presents herself at your consultation and reports that for some time now, “something has been coming out of her anus”. She had been ashamed to go to the doctor about it until now. So far, she has always been able to push it back herself. Now pushing back would become more and more difficult and the constant bleeding and stool smearing was very unpleasant. They have been caring for the patient for years and have prescribed her stool regulation medications several times. The last colonoscopy was more than ten years ago.

Basics

The rectum is responsible for the reservoir function of the intestine before excretion. Rectal prolapse is defined as a prolapse of the full wall of the rectum through the anus, with loss of its function. Basically, an external rectal prolapse can be distinguished from an internal rectal prolapse (intussusception).

The incidence of rectal prolapse is approximately 2-3 per 100,000 population with a relatively low prevalence of 0.5% in the overall population.

In addition to an external painful prolapse of the rectum, mucus and/or blood discharges up to various stages of fecal incontinence can be inquired about anamnestically, which often manifests itself in fecal smearing that is unpleasant for the patient. Recurrent external prolapse of the rectum through the anal canal usually causes chronic overstretching of the sphincter apparatus with associated incontinence of varying severity. However, more than half of those affected also experience defecation disorders with incomplete emptying due to the rectum being turned in on itself by a valve mechanism. Further, urinary incontinence and/or vaginal prolapse can cause discomfort and thus increase patient suffering. The various complaints provoked by coughing, sneezing or pressing should be asked about in the detailed anamnesis, as these often go unmentioned out of shame. Due to the distressing symptoms, the quality of life of those affected is often significantly reduced on a physical and psychological level.

The exact etiology of the symptom complex is not yet fully understood. Rectal prolapse, however, is not a clinical picture in its own right, but rather a symptom of a pelvic floor insufficiency that often has multifactorial causes. Evidence of a deep Douglas space, a wide sphincter, a loosened diastatic levator ani muscle, and a loosened fascial attachment to the presacral fascia can be found in most.

In theory, all age groups can be represented in the affected patient population: The occurrence peaks in practice from the age of 50 and affects more than ten times as often the female sex (up to 90%). General pelvic floor weakness in women may be favored by childbirth.

Diagnostics

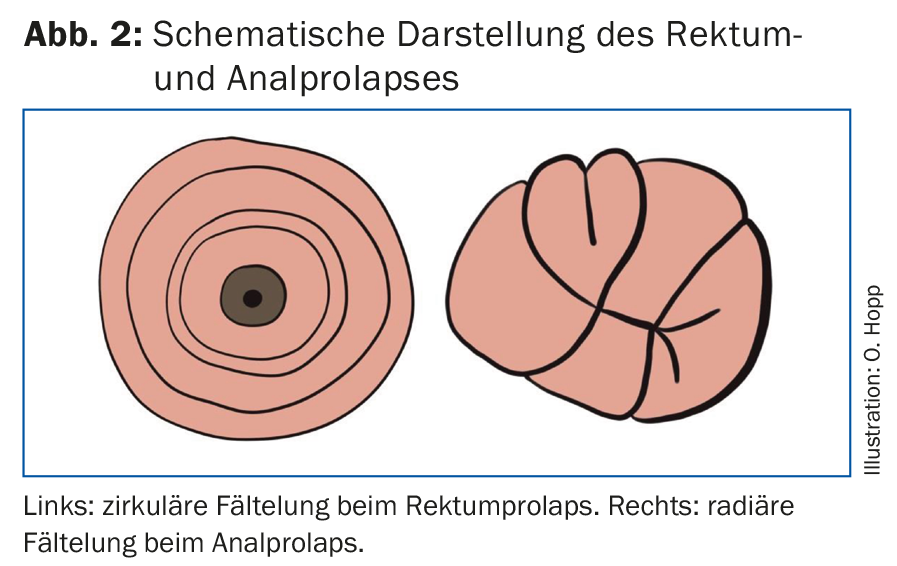

The diagnostic examination should be performed in either the lithotomy position or the strict lateral position with the legs drawn up (Fig. 1). If prolapse does not occur immediately, patients should be asked to push as if going to the toilet. Rectal prolapse is recognized by the circular folding and must be distinguished from anal prolapse, which is diagnosed by the radial folding (Fig. 2) . Both differ in the subsequent therapy.

It is not uncommon to see ulceration on inspection; contact bleeding can easily occur due to mechanical irritation of the recurrent prolapse. Perianal eczema is recognizable by irritation and redness around the anus, is sometimes moist, and may have ulceration or scratch marks. The presence of eczema, in addition to fecal smearing in the linen, indicates a disorder of fine continence. The prolapse should be carefully reduced and a digital rectal examination (DRU) performed. In this case, sphincter insufficiency can often be detected, during pinching and even at rest. In internal prolapse, impingement of the rectum occurs during DRU under pressing. During the examination, it is also possible to understand whether spontaneous reduction occurs or whether manual reduction is required and the condition has progressed accordingly.

A proctoscopic examination should also be performed to visualize intussusception and evaluate the mucosa. Colonoscopy must be performed as part of a follow-up diagnostic workup prior to rectal surgery to rule out concomitant pathologies. It is recommended anyway from the age of 50 for general preventive care. In this case, it should be kept in mind that laxation, especially for elderly patients, can become a torture due to recurrent prolapsing of the rectum. For this reason, these should be prepared under inpatient conditions or at least outpatient support should be ensured. In addition, MR-defecography can be used as the most sensitive examination method to document the anorectal pathophysiology and its dysfunction.

Therapy

There are countless different surgical options for treating rectal prolapse. Since this is a benign condition, the patient’s age and concomitant diseases as well as the degree of suffering should be taken into account in addition to the extent of the prolapse. If the prolapse is detectable as part of a combined pelvic floor disorder, an interdisciplinary discussion between gynecologists, urologists and proctologists is advisable in order to develop a customized therapy concept. Conservative therapy is possible, if at all, only in small prolapse in polymorbid patients by means of good stool regulation.

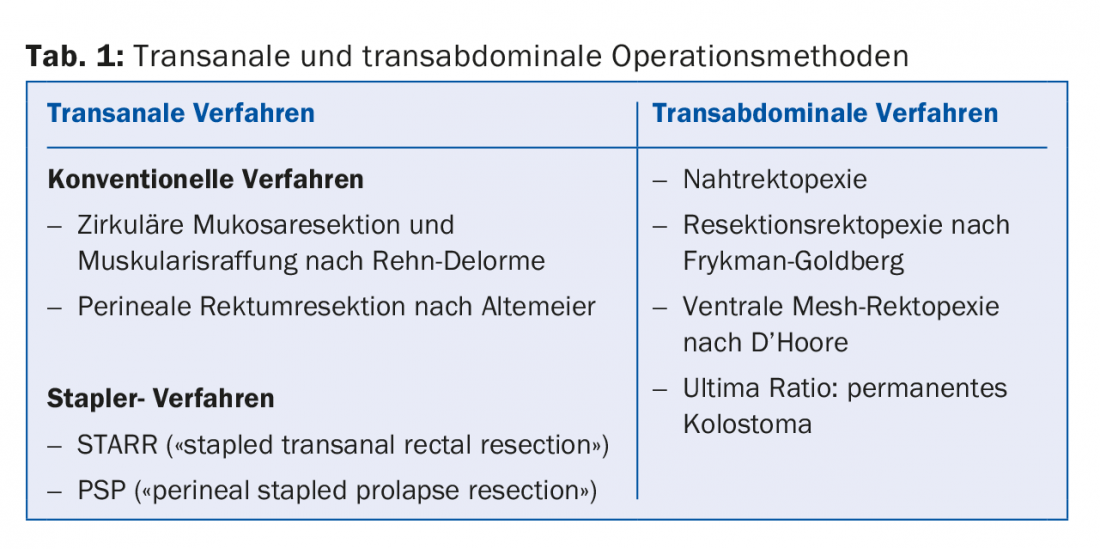

Basically, a distinction must be made between transanal and transabdominal (today usually laparoscopic) surgical methods (Tab. 1).

Transanal surgery can be performed under regional anesthesia and is therefore suitable for polymorbid patients. In Rehn-Delorme surgery, the excess mucosa is resected and the underlying muscle layer is tightened with sutures in an accordion fashion. For larger prolapses, the Altemeier operation is an option. A full-wall resection with end-to-end coloanal anastomosis is performed. Stapler surgery (STARR, PSP) is characterized by a shorter surgical time with less blood loss, but is associated with significantly higher costs because of the special stapling devices. Recurrence rates of 4-60% are reported in the literature for all transanal procedures.

Modern anesthesia techniques have significantly reduced the surgical risk for laparoscopic procedures but also for polymorbid patients. The main advantage of transabdominal surgery is the ability to treat coexisting pelvic floor pathology. Among the various transabdominal surgical procedures, D’Hoore laparoscopic ventral mesh rectosacropexy seems to be gaining acceptance. In this procedure, the rectum is mobilized or stretched anteriorly, sparing the dorso-lateral autonomic nerves, and then a synthetic or biological mesh is fixed between the distal rectum and promontory. This surgery can be performed conventionally-laparoscopically or robotically-assisted. In case of concomitant constipation or pathology at the sigmoid colon (pronounced sigmoid diverticulosis, recurrent diverticulitis), an additional sigmoid resection should be considered (resection-rectopexy with/without mesh); it must be kept in mind that the anastomosis extends the risk profile for the intervention accordingly by the anastomotic complication (insufficiency, bleeding, stenosis). Transabdominal surgery restores the anatomy of the anorectal junction, or the posterior and middle pelvic compartments. Enterocele and rectocele can be corrected at the same time. The rectal ampulla is preserved with its reservoir function, in contrast to transrectal surgery. In most cases, all of this leads to significant improvement of incontinence and defecation disorder and thus to an improvement in the quality of life. However, in cases of preoperative sphincter weakness, repair of the prolapse may result in troublesome fecal incontinence. Then, in principle, the possibility of a permanent colostomy should also be considered as a last resort in elderly patients. Several studies demonstrate that laparoscopic ventral rectopexy can be performed safely and gently even in elderly patients. Serious complications (postoperative bleeding, bowel or vaginal injuries) are extremely rare; mesh-related complications (erosion, migration, stricture) can be expected in 1-3% of cases. In a large 2018 Finnish study of over 500 patients, the recurrence rate was 7.1% [1].

In contrast, large comparative studies (PROSPER study 2013 [2], Cochrane analysis 2015 [3]) show no significant differences in recurrence rate and with regard to residual mucosal prolapse, incontinence, and constipation between the procedures. In the PROSPER trial, the recurrence rate ranged from 13 to 26%, depending on the procedure.

However, a recent registry study from Denmark with over 1600 patients showed a significantly higher re-operation rate (mainly due to recurrence) of 26% after transanal surgery vs. 10% after transabdominal surgery [4].

Based on the current data situation, it is not possible to conclusively answer which procedure is best used for which patient. In our opinion, laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy according to D’Hoore is the surgical method of choice in “fit” patients, since the anatomical conditions are reconstructed and the autonomic nerve structures are spared. Transanal surgery is reserved for the elderly, polymorbid patients or small prolapse.

In the present case of Mrs. H., an external rectal prolapse was diagnosed, which significantly limited her quality of life. Because she had no relevant secondary diagnoses despite her advanced age, we performed a laparoscopic procedure using D’Hoore mesh rectopexy. Laxation for colonoscopy was troublesome for the patient, but possible under inpatient conditions. The subsequent colonoscopy showed only moderate sigmoid diverticulosis except for a few polyps that could be ablated, which had not caused any symptoms so far. Therefore, we did not perform a sigmoid resection. The patient showed grade I incontinence (wind cannot be held) after recovery.

Take-Home Messages

- Rectal prolapse is not a clinical picture in its own right, but a symptom of a frequently multifactorial pelvic floor insufficiency.

- Rectal prolapse is recognized by the circular folding and must be differentiated from anal prolapse, which is diagnosed by the radial folding.

- Laparoscopic ventral mesh rectopexy according to D’Hoore is the best therapeutic option in the absence of contraindications and the procedure favored by us at the Frauenfeld Cantonal Hospital.

- Transanal surgery is reserved for the elderly, polymorbid patients or small prolapse.

Literature:

- Mäkelä-Kaikkonen J, et al: Does ventral rectopexy improve pelvic floor function in the long term? Dis Colon Rectum 2018; 61: 230-238.

- Senapati A, et al: PROSPER: a randomised comparison of surgical treatments for rectal prolapse. Colorectal Dis 2013; 15: 858-870.

- Tou S, et al: Surgery for complete (full-thickness) rectal prolapse in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2015; 11. art. No.: CD001758.

- Bjerke T, et al: One decade of rectal prolapse surgery: a national study. International Journal of Colorectal Disease 2018; 33: 299-304.

Further reading:

- Bordeinaou L, et al: Rectal prolapse: an overview of clinical features, diagnosis, and patient-specific management strategies. J Gastrointest Surg 2014; 18(5): 1059-1069.

- D’Hoore A, et al: Long-term outcome of laparoscopic ventral rectopexy for total rectal prolapse. Br J Surg 2004; 91: 1500-1505.

- Gingert Ch, et al: Rectal prolapse, Coloproctology, Georg Thieme Verlag 2016.

- Kairaluoma MV, Kellokumpu IH: Epidemiologic aspects of complete rectal prolapse. Scand J Surg 2005; 94: 207-210.

- Matzel KE, et al: Rectal prolapse-abominal or local approach. Surgeon 2008; 79: 444-451.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(6): 19-22