Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease of as yet unclear etiology. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is based on the typical clinical presentation and histologic evidence of non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas, after exclusion of other differential diagnoses. Since in more than 90% of sarcoidosis patients the lungs resp. the intrathoracic lymph nodes are involved, the diagnosis is often made by means of biopsies obtained by bronchoscopy. If indicated, the therapy is carried out with immunosuppressants resp. Immunomodulators.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystemic granulomatous disease of as yet unclear etiology [1]. It is characterized by non-necrotizing, epithelioid cell granulomas in various organs and therefore has a variable clinic according to organ involvement. There is no specific diagnostic test, so diagnosis is based on typical clinical findings, detection of the typical granulomas, and exclusion of differential diagnoses.

The prevalence of sarcoidosis is estimated at 1-40/100,000 population worldwide, although varying case definitions, variable clinical presentation, and ultimately the occasional difficulty in making a diagnosis make accurate quantification difficult [2,3]. Furthermore, a “North-South divide” with higher prevalence in Scandinavia has been described [4]; in the ACCESS study, it was confirmed that African Americans have more frequent and severe disease [5].

In Switzerland, a lifetime prevalence of 121/100,000 was found for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis (130/100,000 men, 112/100,000 women). A prevalence of 44/100 000 was calculated for active sarcoidosis and 16/100 000 for sarcoidosis requiring hospitalization. The average annual incidence in Switzerland is estimated at 7/100,000 population [6].

Disease is possible at any age, although younger adults (<40 years) are more likely to develop the disease; a second peak of disease exists for the female sex at >50 years of age [7]. In Switzerland, the median age at diagnosis is 45 +/- 15 years (41 +/- 14 years for men, 48 +/- 15 years for women) [6].

Cause and pathogenesis

The causes of sarcoidosis are not known. Various hypotheses are discussed in the literature. The disease is likely triggered by inhalation of an agent/antigen (pathogen, aerosol) in genetically predisposed patients, supported by the observation of a clustered incidence of sarcoidosis in the first year after the 9/11 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York among dust-exposed firefighters [8]. In Switzerland, an increased prevalence was observed in regions with metal processing industry and with agriculture (potato and grain processing and cultivation of meadows) [6]. Because of the feature of granulomatous disease, exposure to mycobacteria or other pathogens has also been discussed but never proven.

The observation of a familial as well as ethnic clustering suggests that there is a genetic background [9]. Different alleles – mainly of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) and the ACE gene – have been studied, identifying genotypes more frequently associated with sarcoidosis [10]. In turn, some genotypes have been associated with Löfgren’s syndrome and a benign course, among others [11].

Immunologic processes are involved in the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis, although these are not yet understood in detail. The immune response is presumably triggered by the presentation of an undefined antigen by macrophages to CD4+ T lymphocytes via MHC class II receptors. The chemokines and cytokines (including TNF-α, IL-2) released during this process lead to the formation of the typical granulomas consisting of epithelioid cells, multinucleated giant cells, and CD4+ T lymphocytes [12–14]. It is not known which mechanisms cause the disease to be self-limiting on the one hand and chronically progressive on the other.

Diagnosis

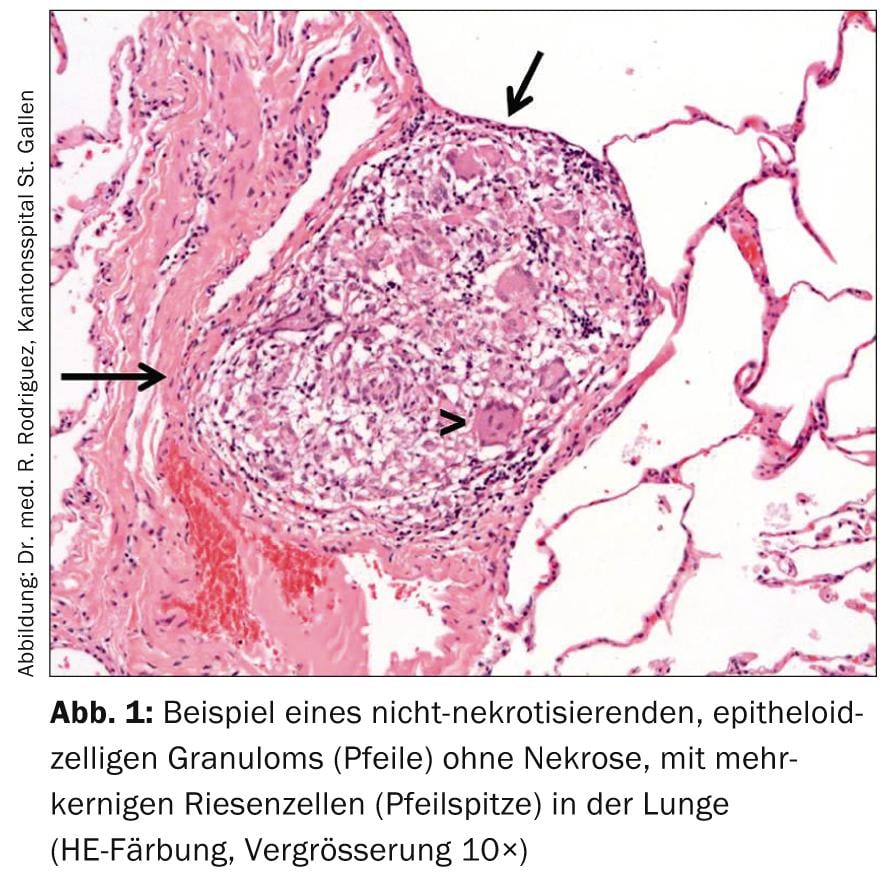

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis is made with a typical clinical picture, histopathologic evidence of non-necrotizing epithelioid cell granulomas (Fig. 1), and after exclusion of differential diagnoses.

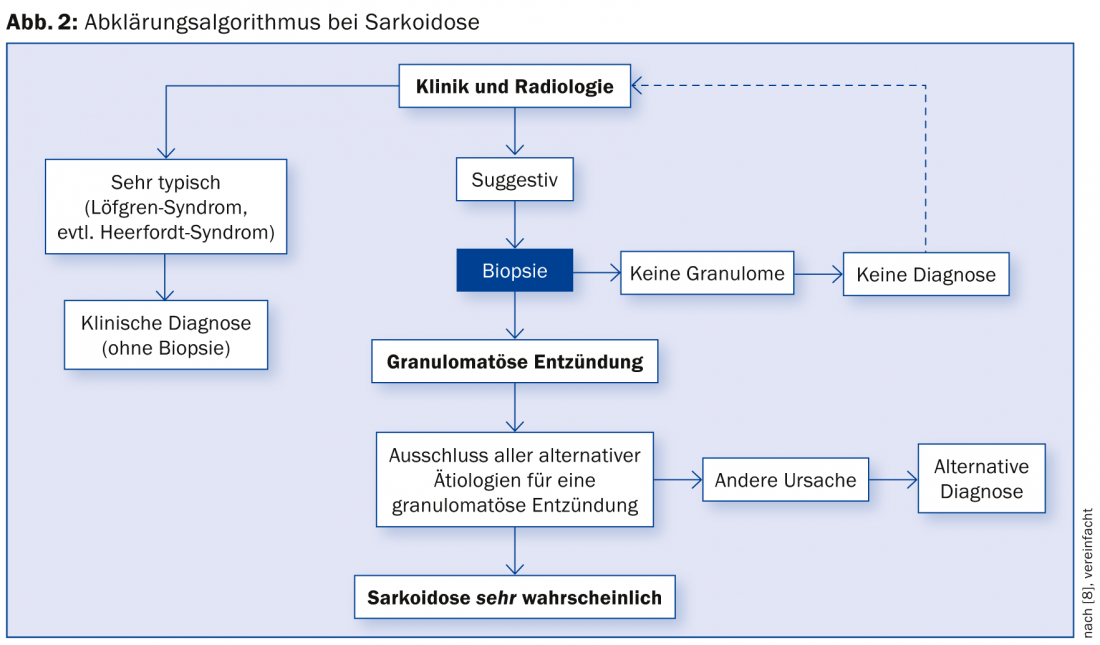

A possible diagnostic algorithm is summarized in Figure 2 [15].

Typical symptoms

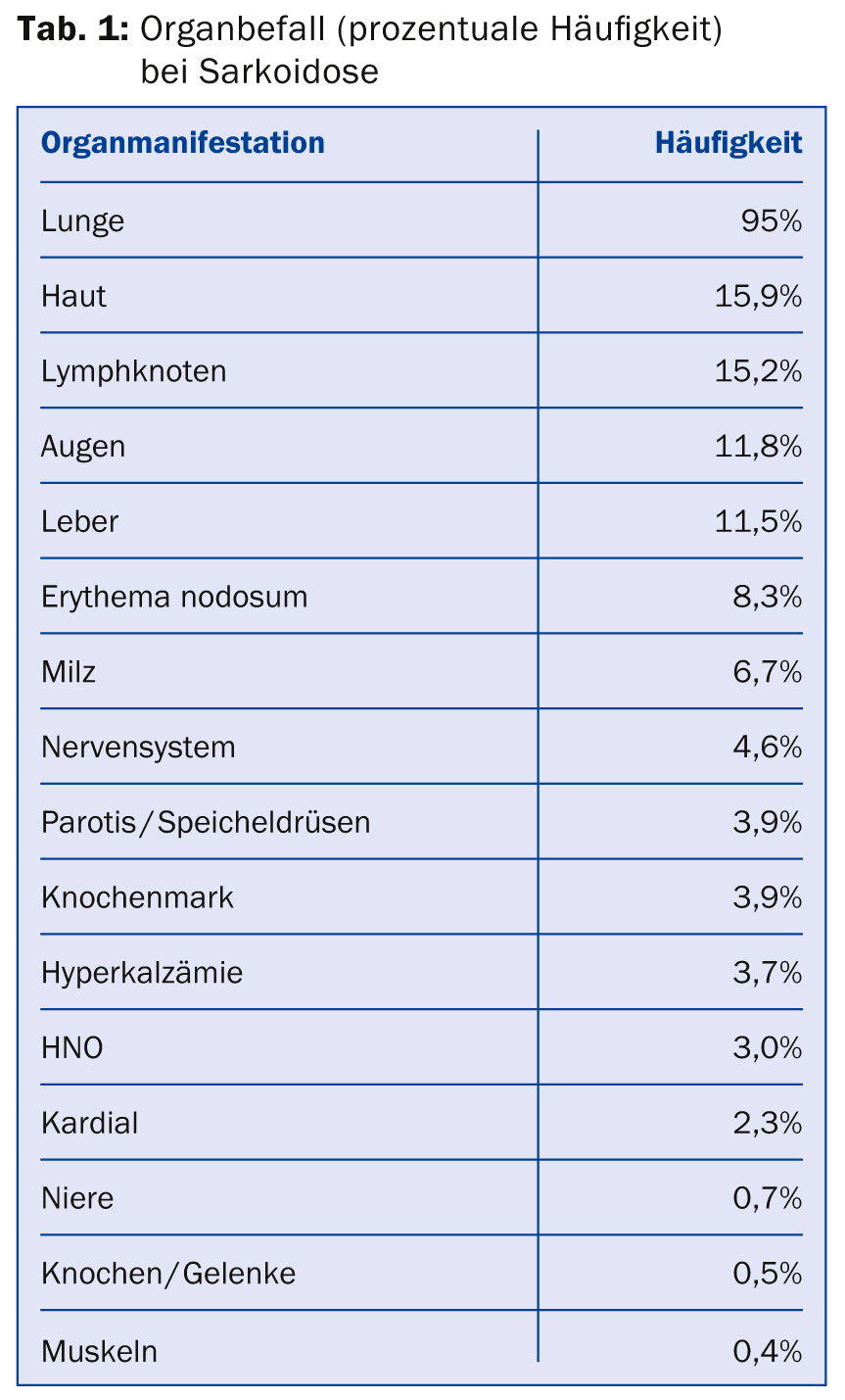

Typical granulomas can develop in any organ. The hilar and mediastinal lymph nodes, lung tissue, skin, and extrathoracic lymph node stations are frequently affected. Less frequently, ophthalmologic, neurologic, or cardiac involvement is described (Table 1); when these organs are affected, clinical impairment, morbidity, and mortality are significant [16]. There is no single typical sarcoidosis symptomatology, as virtually all organs can be affected.

Patients are often asymptomatic, so it is not uncommon for sarcoidosis to be an incidental finding of bihilar lymphadenopathy when a conventional radiograph is performed [17].

Because pulmonary manifestations are present in more than 90% of patients, symptoms such as nonproductive cough, dyspnea, and thoracic pain are common. Nonspecific general symptoms such as fever, weight loss, chronic fatigue, malaise, muscle weakness, and exercise intolerance are also often described.

Löfgren syndrome and Heerfordt syndrome

The co-occurrence of bihilar lymphadenopathy, fever, erythema nodosum, and arthralgias/arthritides is termed Löfgren’s syndrome. This clinic is characteristic, so histologic evidence of granulomas may be omitted in this situation. Löfgren’s syndrome has a good prognosis. The rare but specific combination of parotitis with uveitis and peripheral facial paresis (“Bells’ palsy”) with histologically proven sarcoid granulomas is known as Heerfordt syndrome.

Intrathoracic manifestation

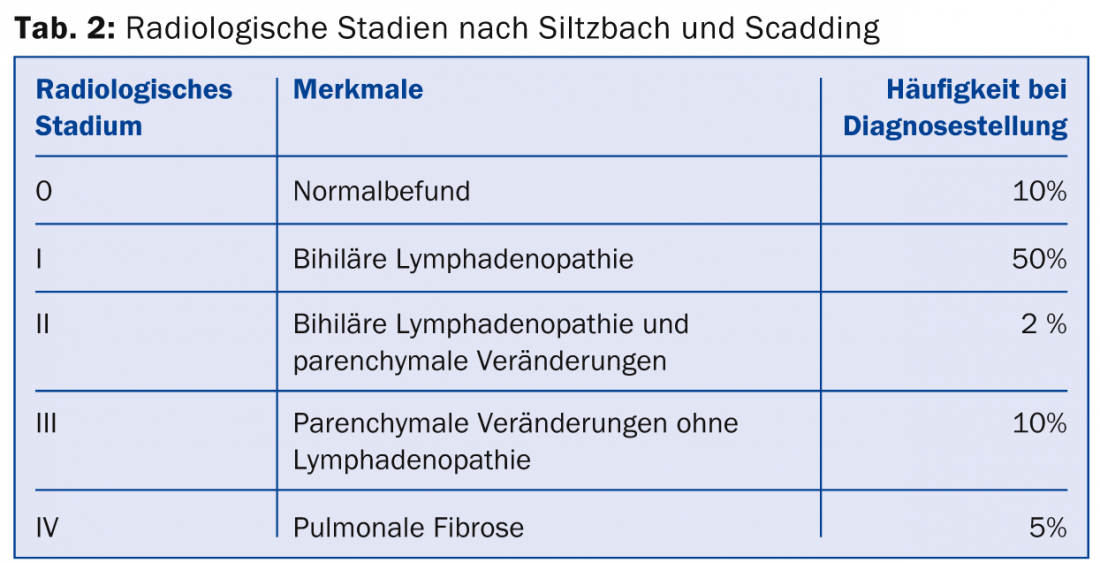

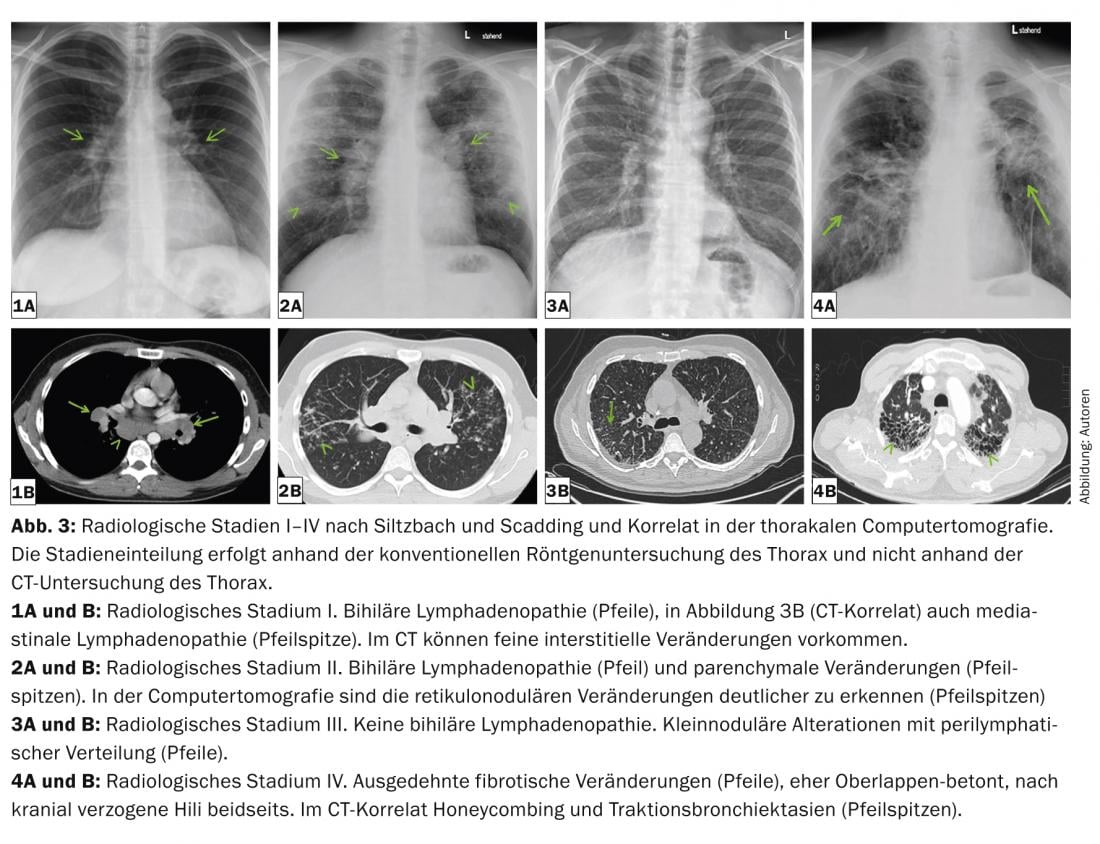

Intrathoracic manifestations range from bihilary lymphadenopathy alone to severe lung parenchymal destruction and the occurrence of pulmonary hypertension (even without pulmonary changes). Pulmonary severity is classified into five radiological stages according to Siltzbach and Scadding based on the conventional radiograph (Table 2 and Fig. 3) [18,19].

Staging is important because prognostic information can be derived from it. Two-thirds of patients experience spontaneous remission within 2-5 years. This is especially true for radiological stages I and II at diagnosis.

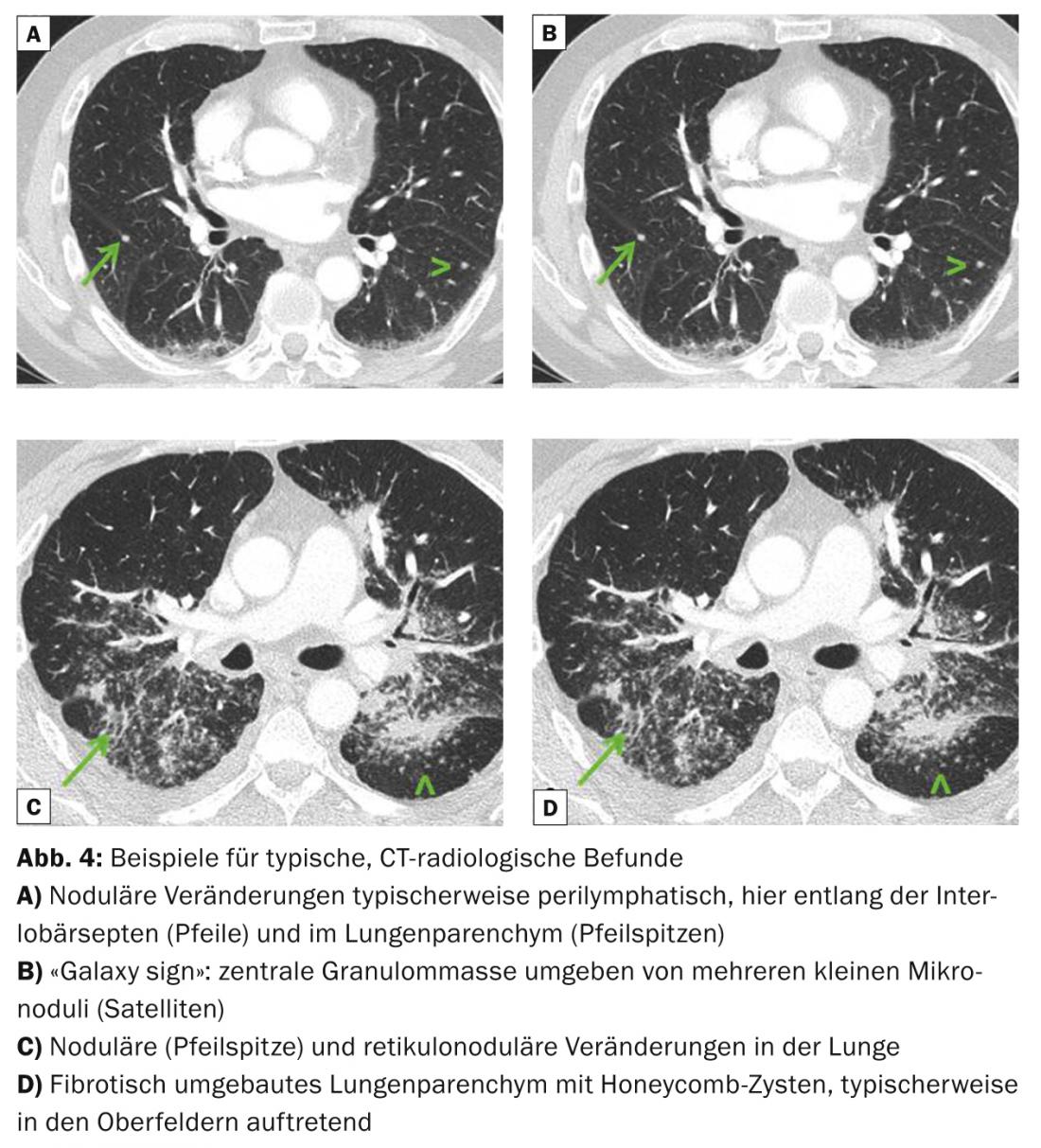

Pulmonary radiological typical images are bihilary, but also symmetrical mediastinal lymphadenopathy, micronodules (diameter <3 mm) with typical distribution (upper and middle fields, along the bronchovascular bundles, subpleural and along the interlobular septa), bilateral macronodules that may rarely melt (reflecting ischemic necrosis of the core of the granuloma), ground-glass opacities, proliferation of reticular drawing, fibrosis with honeycombing, and traction bronchiectasis with emphasis on the upper fields (Fig. 3 and 4). Thoracic computed tomography (“high resolution computed tomography”, HRCT) is more sensitive for assessing discrete changes in the lung parenchyma.

Neurological, cardiac or ophthalmological manifestation

In cardiac sarcoidosis, there are often conduction disturbances in the sense of AV block or intraventricular conduction disturbances in the ECG. Patients may be asymptomatic, experience palpitations, or have syncope or dyspnea. Suffer arrhythmias up to sudden cardiac death. If the myocardium is severely involved, there may be cardiomyopathy with the clinical picture of heart failure. In addition, pericarditis may occur.

Ophthalmologic involvement often manifests as uveitis, optic nerve neuritis, and swelling of the lacrimal glands.

Neurologic involvement most commonly results in cranial (facial nerve palsy) or peripheral neuropathy, meningeal irritation with evidence of lymphocytes in the CSF, or infiltration of the pituitary or pituitary gland. of the hypothalamic region with corresponding endocrinological complications.

The occurrence of hypercalcemia can be threatening, as a result of increased hydroxylation of vitamin D3 in the epithelioid cells of the granulomas.

Skin manifestation

Various skin manifestations are frequently described. Typical are lupus pernio resp. Erythema nodosum, but also maculo-papular and nodular changes (Fig. 5) – frequently also in the area of tattoos and scars. Depending on the localization (face), the skin changes can lead to significant subjective impairment due to disfigurement.

Histological evidence of sarcoid granulomas

Except in Löfgren’s syndrome, histologic evidence of typical granulomas is recommended for diagnosis; these are non-necrotizing, small, sharply circumscribed with some perivascular emphasis and aggregation tendency, and possibly fine-lamellar centripetal fibrosis. (Fig. 2). The selection of the biopsy site should allow for the least invasive procedure possible (e.g., skin biopsy, lacrimal gland biopsy, excision of peripheral lymph nodes).

Only about 2% of all patients with extrapulmonary sarcoidosis do not have pulmonary involvement [16]. Therefore, bronchoscopic techniques are used to try to identify histologic resp. to take cytological samples. In endobronchial lesions (cobblestone-like altered mucosa in up to 50% of patients [20]), a mucosal biopsy can be obtained by forceps biopsy; a positive result can be expected in more than 60% of patients [21]. Using transbronchial lung biopsies, diagnostically useful samples can be obtained in 60-97% of patients (depending on the number of biopsies taken and the extent of radiographic lung parenchymal changes) [22–24], using sonographically guided transbronchial needle aspiration (TBNA) of mediastinal and/or hilar lymph nodes in approximately 80% of patients [25]. The combination of these techniques improves the diagnostic yield, so that mediastinoscopy, which used to be frequently required, is now very rarely used.

Bronchoscopy usually involves bronchoalveolar lavage. Sarcoidosis is likely – though not proven – with evidence of lymphocytic alveolitis (>15% lymphocytes), an elevated CD4/CD8 quotient >3.5, and exclusion of infection (including mycobacteria). The sensitivity of the CD4/CD8 quotient is 42-59% and the specificity is 76-96% for the increase of the quotient >3.5 [26,27].

Using PET/CT technique, inflammatory foci can be visualized as regions of increased FDG uptake in selected cases. If the biopsy site cannot be clearly defined because of the clinical findings, PET/CT technology can be used to try to identify an inflammatory focus.

Differential diagnoses to be excluded

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis with a typical clinical presentation and evidence of the appropriate histopathologic findings can be made when other granulomatous diseases have been excluded. Differential diagnoses include infectious diseases such as tuberculosis, fungal infections (histoplasmosis, coccidioidomycosis), brucellosis or tularemia. These diseases can be excluded by means of bronchoalveolar lavage workup if clinical suspicion is appropriate. However, differential diagnoses also include malignant diseases, in particular lymphomas and carcinomas (exclusion by histopathological findings). Chronic berylliosis can cause a picture very similar to sarcoidosis, especially pulmonarily. To differentiate berylliosis, it is important to obtain an accurate occupational history. If suspected, the diagnosis is made by in vitro stimulation of mononuclear cells from blood or fluid from bronchoalveolar lavage. Furthermore, exogenous allergic alveolitis (history, decreased CD4/CD8 quotient), drug-induced pneumonitis (history) and granulomas in the context of a foreign body reaction (histology) should be excluded. Because sarcoidosis granulomas can also be perivascular, differentiation from vasculitis in biopsy material can be difficult.

Small, sharply circumscribed granulomas in draining lymph nodes, in the surrounding stroma, and also in the liver or spleen of patients with malignancies are referred to as “sarcoid-like reaction”; such granulomas occur in about 4% of patients with carcinomas (including breast cancer and renal and gastrointestinal carcinomas) and somewhat more frequently in patients with Hodgkin’s (14%) and non-Hodgkin’s (7%) malignancies [28].

Another important differential diagnosis when granulomatous disease is detected is common variable immunodeficiency (CVID). This is characterized by low serum immunoglobulin levels, recurrent bacterial infections, and a decreased antibody response. Some of the patients develop granulomatous inflammation with non-necrotizing granulomas in the lungs, spleen, liver, and lymph nodes, among others [29].

Sarcoidosis is treated with TNF-α inhibitors, among other drugs. Paradoxically, granulomatous inflammation has been described during therapy with TNF-α inhibitors, especially etanercept in rheumatoid arthritis, but also infliximab [30]. Noncaseating granulomas may also occur in association with interferon-γ therapy (including in chronic hepatitis C) [31].

Work-up and progress assessment

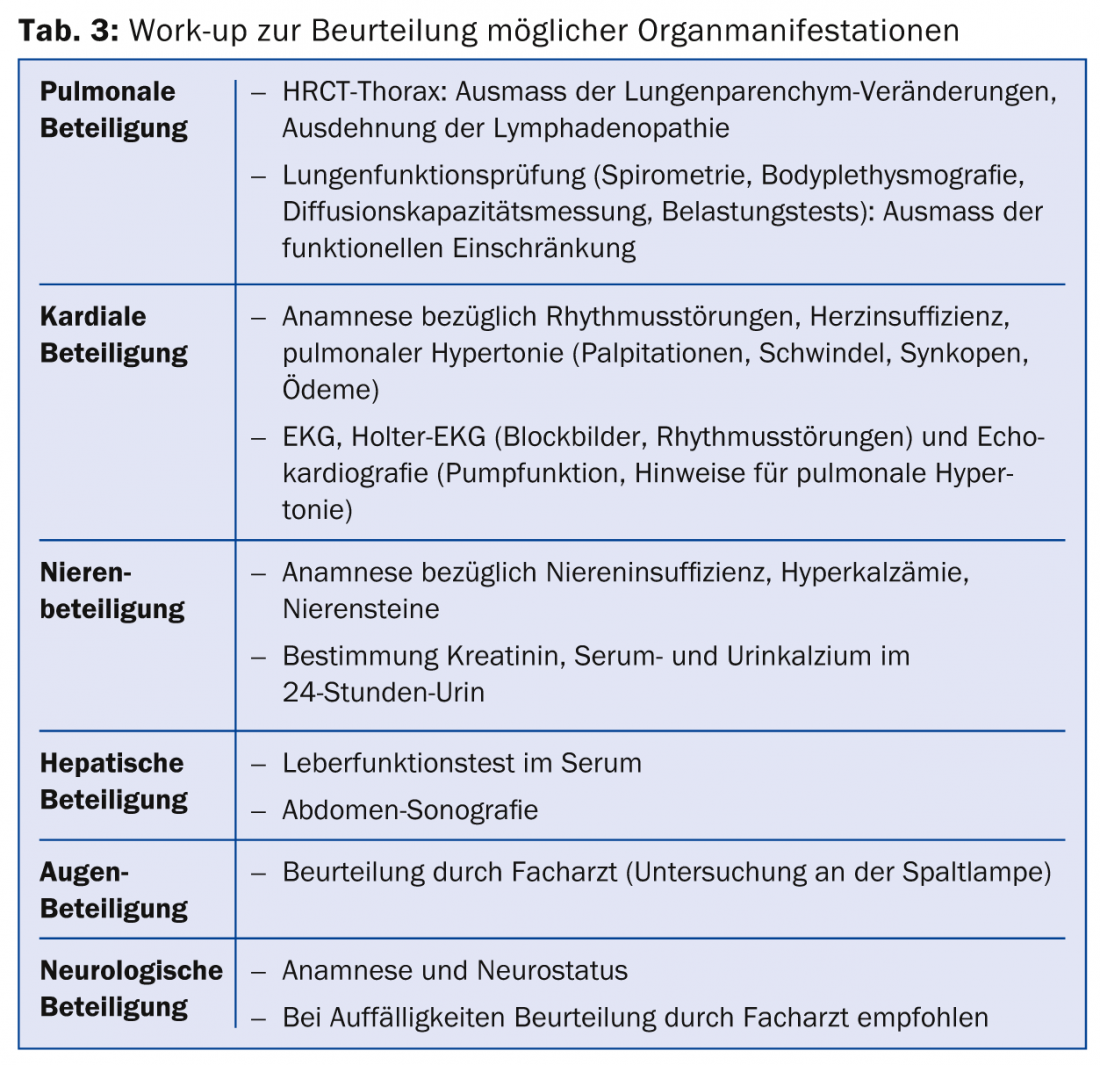

Once a diagnosis of sarcoidosis is made, it is recommended that a work-up be performed regarding the extent of the disease. In particular, organ manifestations that could lead to substantial morbidity should be screened (Table 3).

Furthermore, it should be defined which parameters can be used for the assessment of the course (e.g. also under therapy). Angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) is determined to assess possible medullary involvement. ACE is produced in the epitheloid cells of granulomas in sarcoidosis, among others [32]. However, due to low sensitivity, ACE is not suitable as a diagnostic test. If elevated at diagnosis, ACE is a possible follow-up parameter. Another possible paramenter of progression is the soluble interleukin-2 receptor: antigen-presenting cells produce interleukin 2 (IL-2) in association with granuloma formation. This leads to the activation of T cells. This releases a soluble form of the interleukin-2 receptor (sIL-2 receptor) into the bloodstream. Since an increase in sIL-2 receptor reflects nonspecific activation of T lymphocytes, it can be used to determine disease activity and thus assess progression.

Prognosis and indication for therapy

The course of the disease cannot be predicted. However, the prognosis is favorable in about two-thirds of patients: remission occurs within a decade, and in about 50% of patients within three years. In about one third of patients, the disease progresses chronically with relevant functional impairment of the affected organs. Less than 5% of all patients die from sarcoidosis. Mortality is mainly due to pulmonary fibrosis with respiratory failure, cardiac or neurological involvement, or pulmonary hypertension [33].

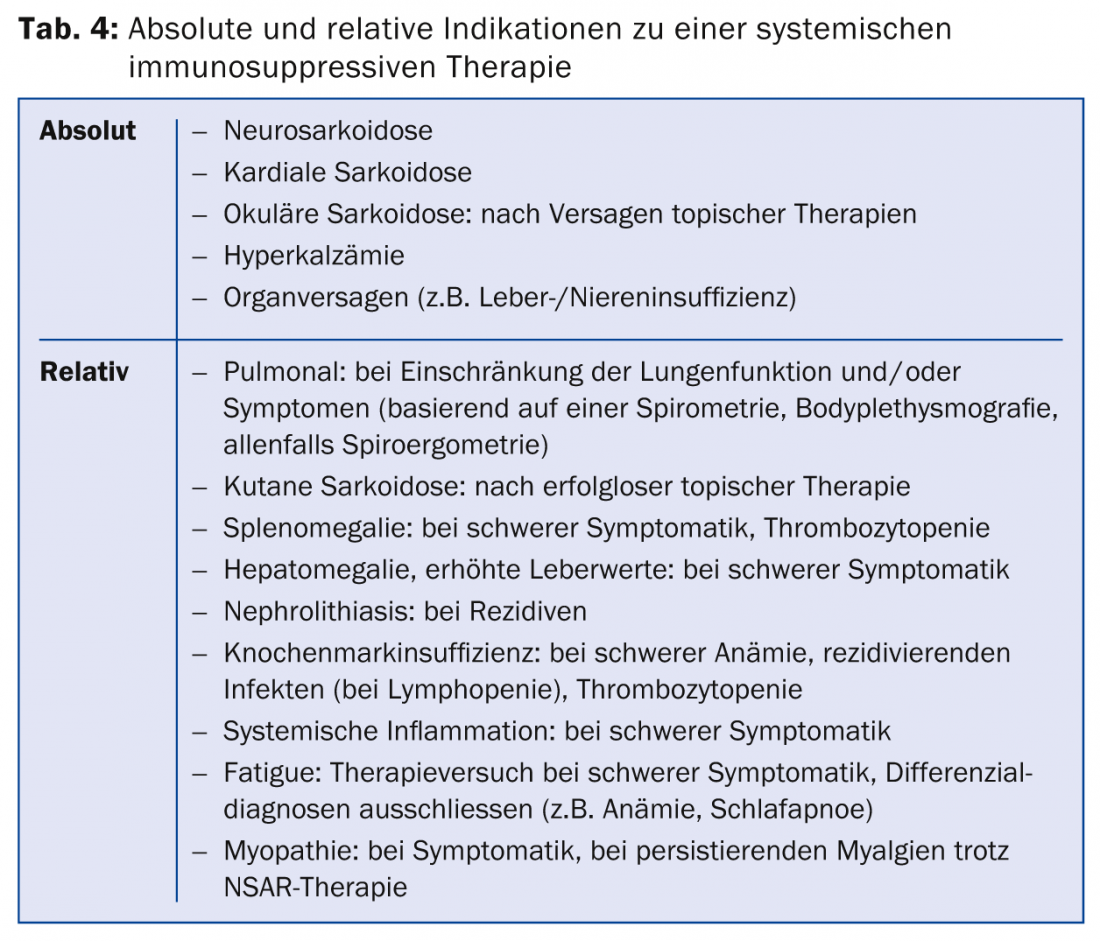

The indication for therapy should be made very carefully, in the knowledge of the usually spontaneously favorable course of the disease, the potential side effects of therapy, and the increased recurrence rate after therapy with immunosuppressants (the postulated antigen persists in the affected organ, so that granuloma formation may recur after therapy cessation). An absolute indication for therapy is neurosarcoidosis, cardiac or ocular sarcoidosis with involvement of the middle or posterior segment of the eye, and severe functional impairment of the affected organs, typically hepatic or renal insufficiency, but also severe pulmonary dysfunction. In the case of mild and moderate limitation, careful clinical follow-up is possible: if symptoms are present and the functional limitation is progressive, thus indicating disease activity, therapy is usually started.

Therapy with immunosuppressants/immunomodulators

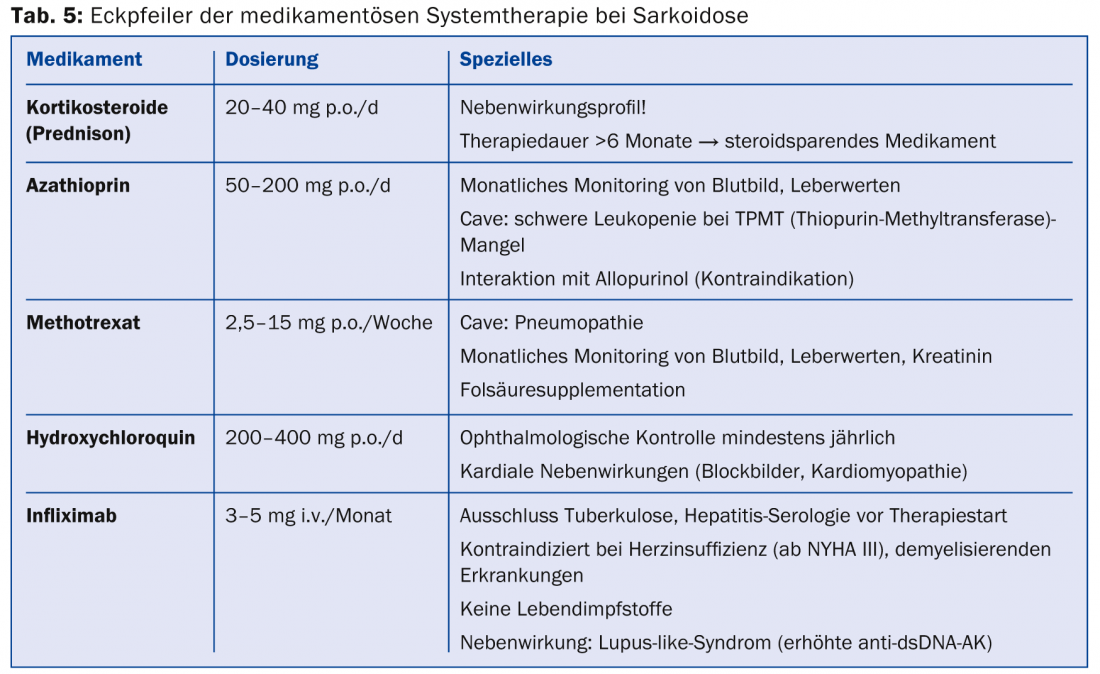

If there is an indication for therapy (Tab. 4), immunosuppressive drugs or Immunomodulators used (Table 5) .

Because of their good and rapid efficacy, corticosteroids are agents of first choice. Doses of 20-40 mg in tapering doses over approximately six months are recommended, but there are no randomized-controlled trials. The use of steroid-sparing agents (azathioprine, methotrexate, leflunomide, mycophenolate) for steroid-associated adverse events should be evaluated early. However, methotrexate should be prescribed cautiously in pulmonary sarcoidosis because of the potential for methotrexate pneumonitis. Since TNF-α is involved in the formation of granulomas, TNF-α antagonists (mainly infliximab) are a good second-line alternative therapy [34,35]. A benefit could be shown especially for the therapy of cutaneous sarcoidosis (lupus pernio) as well as pulmonary and neurological manifestations. The antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine achieves good results in cutaneous sarcoidosis and in hypercalcemia. In Löfgren’s syndrome, symptomatic therapy with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs is well established.

Literature:

- Hunninghake GW, et al: ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society/World Association of Sarcoidosis and other Granulomatous Disorders. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis 1999; 16(2): 149-173.

- Fernandez FE: [Epidemiology of sarcoidosis]. Arch Bronconeumol 2007; 43(2): 92-100.

- Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC: Epidemiology of sarcoidosis: recent advances and future prospects. Semin Respir Crit Care Med 2007; 28(1): 22-35.

- Pietinalho A, et al: The frequency of sarcoidosis in Finland and Hokkaido, Japan. A comparative epidemiological study. Sarcoidosis 1995; 12(1): 61-67.

- Rossman MD, Kreider ME: Lesson learned from ACCESS (A Case Controlled Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis). Proc Am Thorac Soc 2007; 4(5): 453-456.

- Deubelbeiss U, et al: Prevalence of sarcoidosis in Switzerland is associated with environmental factors. Eur Respir J 2010; 35(5): 1088-1097.

- Hosoda Y, et al: Global epidemiology of sarcoidosis. What story do prevalence and incidence tell us? Clin Chest Med 1997; 18(4): 681-694.

- Izbicki G, et al: World Trade Center “sarcoid-like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest 2007; 131(5): 1414-1423.

- McGrath DS, et al: Epidemiology of familial sarcoidosis in the UK. Thorax 2000; 55(9): 751-754.

- Rossman MD, et al: HLA-DRB1*1101: a significant risk factor for sarcoidosis in blacks and whites. Am J Hum Genet 2003; 73(4): 720-735.

- Berlin M, et al: HLA-DR predicts the prognosis in Scandinavian patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997; 156(5): 1601-1605.

- Baughman RP, et al: Release of tumor necrosis factor by alveolar macrophages of patients with sarcoidosis. J Lab Clin Med 1990; 115(1): 36-42.

- Iida K, et al: Analysis of T cell subsets and beta chemokines in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis. Thorax 1997; 52(5): 431-437.

- Pinkston P, Bitterman PB, Crystal RG: Spontaneous release of interleukin-2 by lung T lymphocytes in active pulmonary sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1983; 308(14): 793-800.

- Judson MA: The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med 2008; 29(3): 415-427, viii.

- Baughman RP, et al: Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001; 164(10 Pt 1): 1885-1889.

- Thomas KW, Hunninghake GW: Sarcoidosis. JAMA 2003; 289(24): 3300-3303.

- Siltzbach LE: Sarcoidosis: clinical features and management. Med Clin North Am 1967; 51(2): 483-502.

- Scadding JG: Prognosis of intrathoracic sarcoidosis in England. A review of 136 cases after five years’ observation. Br Med J 1961; 2(5261): 1165-1172.

- Chapman JT, Mehta AC: Bronchoscopy in sarcoidosis: diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. Curr Opin Pulm Med 2003; 9(5): 402-407.

- Shorr AF, Torrington KG, Hnatiuk OW. Endobronchial biopsy for sarcoidosis: a prospective study. Chest 2001; 120(1): 109-114.

- Koerner SK, et al: Transbronchinal lung biopsy for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. N Engl J Med 1975; 293(6): 268-270.

- Gilman MJ, Wang KP: Transbronchial lung biopsy in sarcoidosis. An approach to determine the optimal number of biopsies. Am Rev Respir Dis 1980; 122(5): 721-724.

- Mitchell DM, et al: Transbronchial lung biopsy through fibreoptic bronchoscope in diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Br Med J 1980; 280(6215): 679-681.

- Agarwal R, et al: Efficacy and safety of convex probe EBUS-TBNA in sarcoidosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Respir Med 2012; 106(6): 883-892.

- Costabel U: CD4/CD8 ratios in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: of value for diagnosing sarcoidosis? Eur Respir J 1997; 10(12): 2699-2700.

- Zaiss AW, et al: [T4/T8 ratio in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid: sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of sarcoidosis]. Prax Clin Pneumol 1988; 42 Suppl 1: 233-234.

- Chowdhury FU, et al: Sarcoid-like reaction to malignancy on whole-body integrated (18)F-FDG PET/CT: prevalence and disease pattern. Clin Radiol 2009; 64(7): 675-681.

- Ardeniz O, Cunningham-Rundles C: Granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency. Clin Immunol 2009; 133(2): 198-207.

- Khasnis AA, Calabrese LH: Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors and lung disease: a paradox of efficacy and risk. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2010; 40(2): 147-163.

- Goldberg HJ, et al: Sarcoidosis after treatment with interferon-alpha: a case series and review of the literature. Respir Med 2006; 100(11): 2063-2068.

- Studdy PR, Bird R: Serum angiotensin converting enzyme in sarcoidosis – its value in present clinical practice. Ann Clin Biochem 1989; 26(Pt 1): 13-18.

- Siltzbach LE, et al: Course and prognosis of sarcoidosis around the world. Am J Med 1974; 57(6): 847-852.

- Judson MA, et al: Efficacy of infliximab in extrapulmonary sarcoidosis: results from a randomised trial. Eur Respir J 2008; 31(6): 1189-1196.

- Baughman RP, et al: Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2006; 174(7): 795-802.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2015; 10(3): 10-18