For most people, the death of a loved one is a major life event and is often accompanied by an intense grief reaction. connected. Grief is highly individualized, so it can be difficult to generalize it across people. Persistent grief disorder refers to an unusually long, severe, and debilitating grief reaction. Although there are many similarities, it is important to distinguish ATS from PTSD and depression.

The following article addresses the new diagnosis of persistent grief disorder (ATS), with a particular focus on the practice-relevant areas of diagnosis and therapeutic approaches.

Persistent grief disorder: a new diagnosis

For most people, the death of someone close to them is a life event and is often associated with an intense grief reaction. Grief is highly individualized, so it can be difficult to generalize it across people. In a majority of affected individuals (80-90%), acute grief symptoms usually subside six months after the loss, with affected individuals managing to accept the loss experience and integrate it into their lives [1]. However, there are some people who have unusually long, severe, and debilitating grief reactions. These individuals can now be treated with the new, scientifically proven diagnosis of ATS Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) diagnosed in the eleventh version of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-11) of the World Health Organization (WHO) [2], whereas previously they could only be described in a makeshift way with diagnoses such as depressive disorder [3].

The prevalence of ATS is estimated by large-scale studies to be approximately 10% worldwide [1]. In certain populations that are more frequently affected by conflict, war, and high mortality rates, prevalence is higher, ranging from 54% to 76% in the example of refugees [4,5].

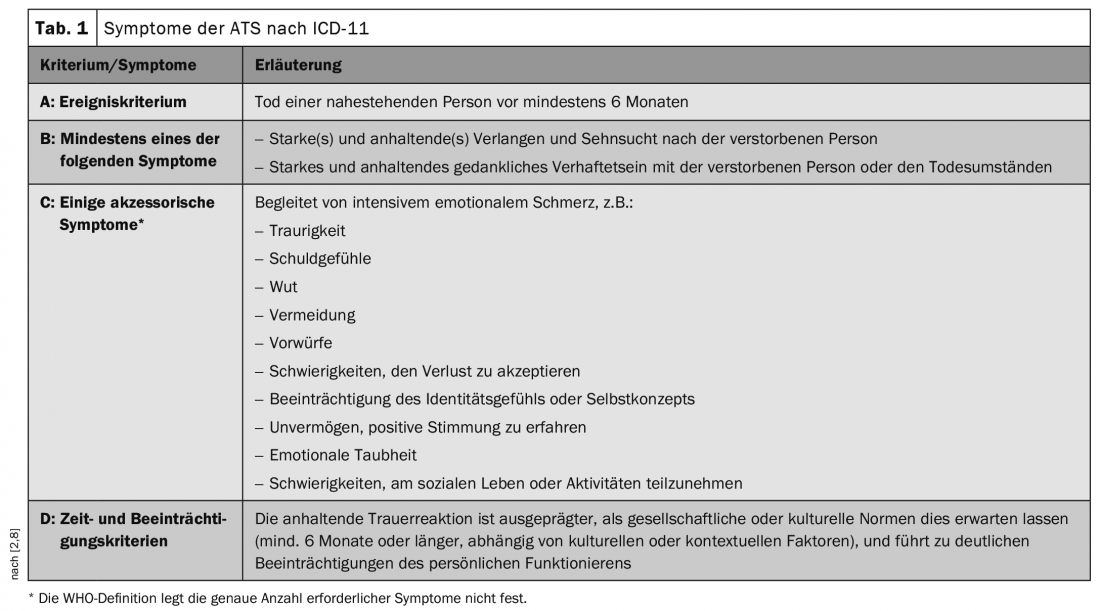

Diagnostic criteria according to ICD-11

Qualitatively, pathological grief is not significantly different from healthy grief (also called normative grief) [6], however, in terms of

- Duration and intensity of symptoms

- as well as the extent of the experienced impairment in functioning in important areas of life.

Thus, the symptom domains are less decisive for a diagnosis than the severity and duration of the symptomatology, as well as the clinically significant level of suffering [7].

The new definition of ATS according to ICD-11 includes an intense and prolonged grief reaction, which is characterized by a strong longing for and/or mental attachment to the deceased person, accompanied by emotional pain [8]. Affected individuals also suffer significant impairment in various functional areas (e.g., occupational, social). Very recently, the ATS definition has been very similar to the text revision of the U.S. DSM-5-TR system. Specifically, the criteria may manifest as, for example, a continuing preoccupation with the circumstances of the death or with keeping the deceased person’s possessions. It is also possible to oscillate between avoiding thoughts of the deceased person and excessive mental preoccupation with him or her. Likewise, those affected often struggle with problems coping with everyday life without the deceased person, difficulty trusting, difficulty evoking positive memories of the loved one. Furthermore, many affected individuals have difficulty engaging in (social) activities, show increased social withdrawal, and struggle more often with the feeling that life is meaningless. In addition, increased substance use (including tobacco, alcohol), increased suicidal ideation, and increased suicidal behavior may occur. Also significant to the new definition of ATS is the culture criterion, which requires that a grief reaction exceed the typical duration (at least six months) and intensity in the individual’s cultural or social context for a diagnosis to be assigned. This means that in assigning a diagnosis, consideration of cultural, social and religious norms, as well as individual circumstances, are crucial. The minimum duration of six months specified by ICD-11 can be understood more as a rough guide. In addition, intercultural differences must be taken into account in the expression of grief, whereby in certain cultural circles, for example, visions or hallucinations in which affected persons see the deceased person are part of the normal mourning process, whereas in others this would be considered pathological (Table 1) [3].

Differential diagnostics

As a makeshift, grief states requiring treatment have often been described with diagnoses such as depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) [2]. Although there are many similarities, it is important to differentiate ATS from it in terms of differential diagnosis. This is particularly relevant for accessing therapy tailored to ATS, which shows significantly higher efficacy in ATS than nonspecific therapies or therapies tailored to other grief-related diagnoses (e.g., depression) [9].

Differentiation Depression [2]: Some symptoms, such as sadness or social withdrawal, occur in both depression and ATS. However, in distinguishing the diagnoses, it is important to note that in ATS, symptoms relate specifically to the loss of the loved one, whereas in depression they encompass multiple areas of life. In addition, some symptoms typical of ATS (e.g., anger over loss, difficulty trusting, etc.) are not characteristic of depression. Finally, the timing of symptom onset in relation to loss must also be considered in ATS.

Differentiation PTSD [2]: It is particularly important to differentiate from PTSD following a death that occurred under traumatic circumstances. Although memories of the death play a role in both cases, in PTSD sufferers experience the situation associated with the death as if it were happening again in the here and now (flashbacks), whereas in ATS sufferers are more preoccupied with memories of the circumstances of the death without experiencing it as if it were happening in the here and now. In addition, feelings of fear of re-experiencing are more prevalent in PTSD, whereas sadness and longing are more prevalent in ATS (Table 2).

Psychotherapeutic treatment approaches

In the psychotherapeutic treatment of ATS, there should be much room for appreciation of the affected person. The tragedy of loss, as well as the accompanying grief of the bereaved, should always be acknowledged and validated. Due to frequent fear or guilt in changing the bond with the deceased person, a cautious approach and an empathic attitude is essential. The goal of therapy should be emotional processing and adjustment to the new life situation, not severing the relationship with the deceased person. In addition, it is important to consider cultural aspects, such as the inclusion of culture-specific rituals. At the end of therapy, positive memories of the deceased person and the development of (new) life goals should be brought to the fore. The following are particularly effective approaches to treating ATS (see also [10] for a more detailed explanation of various treatment approaches to ATS).

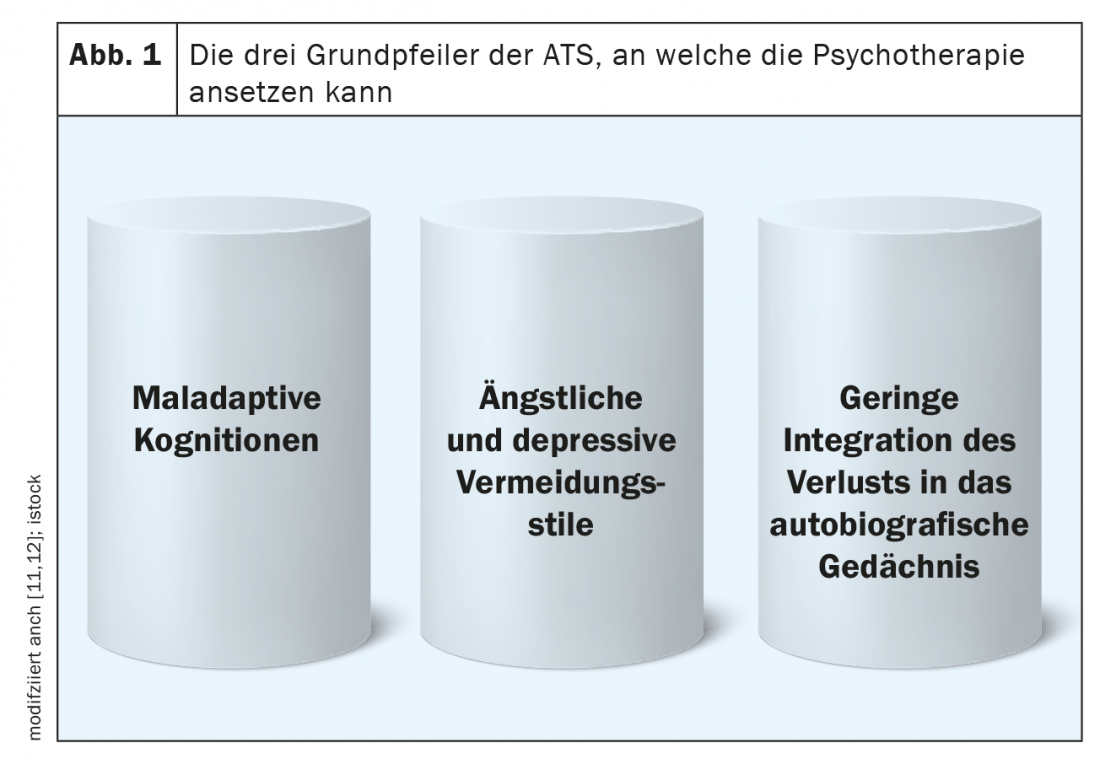

Cognitive behavioral therapy according to [11,12]

According to recent research, three key processes are critical to the development and maintenance of ATS: 1. negative appraisal of grief response or maladaptive core beliefs; 2. anxious and depressive avoidance styles (e.g., social isolation); 3. low elaboration and integration of the loss into autobiographical memory (Fig. 1) . Psychotherapy should start with these three pillars of ATS.

At the beginning of therapy, the diagnostic process focuses on which of the above three processes is most involved in maintaining ATS and is selected as the focus of treatment. In the case of a lack of integration in autobiographical memory, for example, graduated exposure in sensu (in the imagination) and writing tasks are suitable, whereas in the case of anxious avoidance behavior, exposure in vivo (in reality or in relation to stressful situations) is advised. Additionally, behavioral activation occurs with depressive avoidance symptomatology, while Beck cognitive restructuring is appropriate with dysfunctional cognitions and core beliefs. In the latter, maladaptive or unhelpful thoughts (e.g., “I’ll never be happy again!”) are systematically replaced with pleasant and helpful thoughts, which can also achieve change on an emotional level. Cognitive procedures or exposure are also good when there is a strong, mental preoccupation with the event or loss.

In a study by Boelen et al. (2007), the effectiveness of the cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) presented here was studied in 54 bereaved individuals. Here, the intervention of Boelen et al. (2007) compared with supportive therapy, i.e., nonspecific support for grieving individuals. CT was significantly superior to supportive therapy in terms of grief symptoms and general psychological distress, which persisted until catamnesis, indicating a long-term effect of the intervention. The studies on the procedure by Boelen et al. (2006; 2007) were able to illustrate that psychotherapy tailored to ATS is significantly more effective and has a long-term impact compared to nonspecific support for grieving individuals.

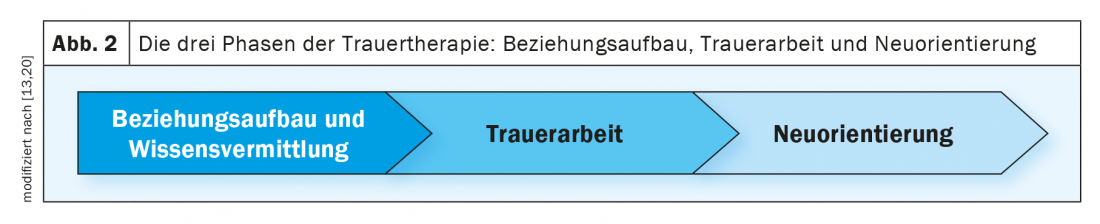

Integrative cognitive behavioral therapy according to [13]

Three-phase integrative cognitive-behavioral therapy (PG-CBT) integrates elements from different therapeutic modalities. In addition to KVT techniques, Gestalt therapy interventions are also woven into the treatment process. In addition, various art therapy interventions are used in the inpatient setting. In the 1st phase of therapy, good relationship building is addressed, ambivalences regarding change are discussed, and mementos are considered in relation to the loss. Individual symptoms are classified using models of the development and maintenance of grief, from which interventions are derived. Phase 2 is followed by the processing of the most present grief focus. Depending on the individual, this may focus on feelings of guilt, adapting to changes in living conditions, grief as a means of maintaining attachment to the deceased person, or explaining and working through avoidance symptomatology. Separate from this are confrontations regarding the most painful aspects of loss, exposures in vivo regarding grief-related triggers, and cognitive restructuring techniques. Likewise, gestalt therapy chair work, in which a conversation is held with the deceased person, can be an effective supplement. Finally, in phase 3, the relationship with the deceased person is redefined and a reorientation towards life without this person is made possible by formulating life goals and new activities (Fig. 2).

PG-CBT was tested in an outpatient setting with 51 individuals (Rosner et al., 2014; 2015a) and showed large symptom improvement in a controlled comparison to the waitlist condition, which was also evident after a catamnesis period of 1.5 years [13,14].

Complicated Grief Treatment according to [15]

Complicated Grief Treatment (CGT) has three primary goals: acceptance of loss, reorganization of attachment to the deceased person, and building new life goals. Four therapy phases are distinguished: Phase 1 represents the introductory examination of the symptomatology, the circumstances of death, the relationship to the deceased person, and the individual identification of goals. Ambivalence regarding the therapy, which may occur, for example, through confrontation with stressful memories, is dealt with by motivational interviewing methods throughout the therapy process. Phase 2 focuses on active treatment of core symptoms, such as with the help of exposure in sensu. Characteristic of this approach, exposures are often repeated at short intervals, so that the emotional stress related to loss-related situations continues to decrease. But the goal here is also to create a coherent narrative of loss. Since those affected are often better able to categorize the loss after this process, acceptance for what has happened is also established and the formulation of new life goals is made possible. In phase 3, priority is given to taking stock of the therapy to date and comparing it with the goals set. In phase 4, further exposures may still occur, e.g., if symptom reduction has not reached the desired level.

Cognitive therapy with confrontation according to [16]

Cognitive therapy with confrontation components extends over 10 weeks and includes double-hour group sessions and four confrontation sessions in an individual setting. During the first two sessions, affected individuals receive detailed education about aspects of grief. This is followed by the four individual confrontation sessions, which mainly involve exposure in sensu. Cognitive restructuring and writing tasks take place in group sessions three through eight. Beginning with the 8th session, a build-up of positive memories is addressed, as well as discussion of new life goals. Through the combined group setting of this intervention, Bryant et al. (2014) an effective, time-limited, and flexible intervention for the treatment of ATS (Table 3).

General evidence of efficacy

The effectiveness of all the therapeutic approaches presented here are scientifically well studied and proven. Overall, Currier et al. (2008) [17] and Wittouck et al. (2011) [18] demonstrated medium-high effect sizes (approximately d=0.53) for common ATS therapies. Recent studies also attest to large effect sizes for the well-studied ATS interventions [see, e.g., 14,15,19,20]. Thus, psychotherapy for ATS is considered moderately to highly effective.

Take-Home Messages

- Persistent grief disorder refers to an unusually prolonged, severe, and debilitating grief reaction in which cultural, social, and religious norms, as well as individual circumstances, play a role in the

- diagnosis must be included.

- Although there are many similarities, it is important to distinguish ATS from PTSD and depression. This is relevant to accessing specific ATS therapy, which is significantly more effective than nonspecific therapies or therapies tailored to other grief-related diagnoses.

- Established psychotherapeutic procedures for ATS are considered moderately to highly effective overall.

Literature:

- Lundorff M, Holmgren H, Zachariae R, et al: Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders 2017; 212, 138-149.

- Killikelly C, Maercker A: Persistent grief disorder. In A. Maercker (Ed.), Trauma sequelae disorders 2019, (pp. 61-77). Springer.

- Augsburger M, Maercker A: Specific stress-related mental disorders in the new ICD-11: An overview. Advances in Neurology – Psychiatry 2018, 86(3): 156-162.

- Craig C, Sossou MA, Schnak M, Essex H: Complicated Grief and its Relationship to Mental Health and Well-Being Among Bosnian Refugees After Resettlement in the United States: Implications for Practice, Policy, and Research. Traumatology 2008, 14(4): 103-115.

- Killikelly C, Bauer S, Maercker A: The Assessment of Grief in Refugees and Post-conflict Survivors: A Narrative Review of Etic and Emic Research. Frontiers in Psychology 2018(9); 1957.

- Holland JM, Neimeyer RA, Boelen PA, Prigerson HG (2009): The Underlying Structure of Grief: A Taxometric Investigation of Prolonged and Normal Reactions to Loss. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 31(3), 190-201.

- Maercker A, Brewin CR, Bryant RA, et al: Diagnosis and classification of disorders specifically associated with stress: Proposals for ICD-11. World Psychiatry 2013; 12(3), 198-206.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2021). ICD-11 mortality and morbidity statistics. https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en

- Shear MK, Reynolds CF, Simon NM, et al: Optimizing Treatment of Complicated Grief: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2016; 73(7): 685-694.

- Rosner R, Comtesse H: Therapy of persistent grief disorder. In: A. Maercker (Ed.). Trauma Consequence Disorders 2019, 379-391. Springer.

- Boelen PA, de Keijser J, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J: Treatment of complicated grief: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral therapy and supportive counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 2007; 75(2), 277-284.

- Boelen PA, van den Hout MA, van den Bout J: A cognitive-behavioral con-ceptualization of complicated grief. Clinical Psychology Science and Practice 2006, 13(2): 109-128.

- Rosner R, Pfoh G, Rojas R, et al: Persistent grief disorder: manuals for individual and group therapy. Hogrefe 2015b.

- Rosner R, Bartl H, Pfoh G, et al: Efficacy of an integrative CBT for prolonged grief disorder: A long-term follow-up. Journal of Affective Disorders 2015a, 183: 106-112.

- Shear K, Frank E, Houck PR, Reynolds CF: Treatment of complicated grief: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2005; 293(21): 2601-2608.

- Bryant RA, Kenny L, Joscelyne A, et al: Treating prolonged grief disorder: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry 2014; 71(12), 1332-1339.

- Currier JM, Neimeyer RA, Berman JS: The effectiveness of psychotherapeutic interventions for bereaved persons: A comprehensive quantitative review. Psychological Bulletin 2008; 134(5), 648-661.

- Wittouck C, van Autreve S, de Jaegere E, et al: The prevention and treatment of complicated grief: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review 2011, 31(1): 69-78.

- Papa A, Sewell MT, Garrison-Diehn C, Rummel C: A randomized open trial assessing the feasibility of behavioral activation for pathological grief responding. Behavior Therapy 2013, 44(4): 639-650.

- Rosner R, Pfoh G, Kotoučová M, Hagl M: Efficacy of an outpatient treatment for prolonged grief disorder: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Journal of Affective Disorders 2014, 167: 56-63.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2021; 19(6): 6-10.