Multiple sclerosis is the most common neurological disease in young adults. Already at a young age it can lead to permanent disability, but the disease activity at the beginning of the disease seems to be relevant for the later course. The early start of an efficient therapy is therefore important. With recently completed clinical trials and recent promising research results, an increase in therapeutic options is expected in the coming months and years.

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the most common autoimmune disease of the central nervous system (CNS), the pathophysiological basis of which remains unclear in detail. Based on the new McDonald 2010 criteria, the diagnosis of MS is often made after the first clinical episode [1]. In most cases there is a relapsing course (“relapsing remitting multiple sclerosis”, RRMS).

During the course of the disease, many patients experience a secondary chronic progression of symptoms independent of relapses (“secondary progressive MS”, SPMS); after ten years, this is the case in about 30-40% of patients [2]. Primary chronic progression (“primary progressive MS”, PPMS) is present in 10-20% of patients, and this course may include superimposed relapses [3].

The initial stage of RRMS often corresponds formally to a clinically isolated syndrome (CIS). In CIS patients, the 2010 McDonald criteria for the diagnosis of RRMS are not met, but the presence of MS must often be assumed as probable [4].

The processes in the early phase of the diseases seem to have a significant influence on the further course of the disease, so that an early start of therapy is important. The formal transition of CIS into clinically confirmed MS can be delayed and the further course positively influenced by the early use of basic therapy [5, 6].

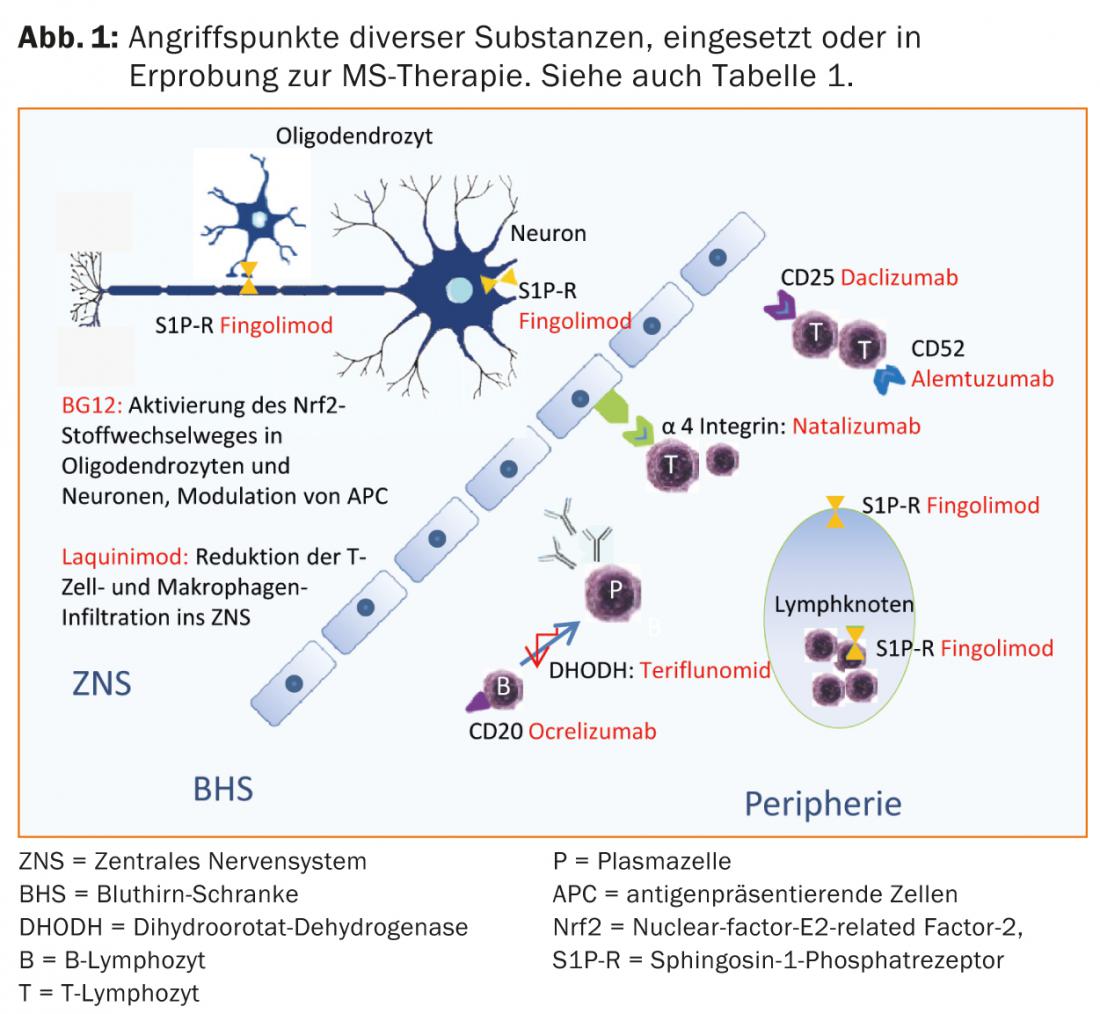

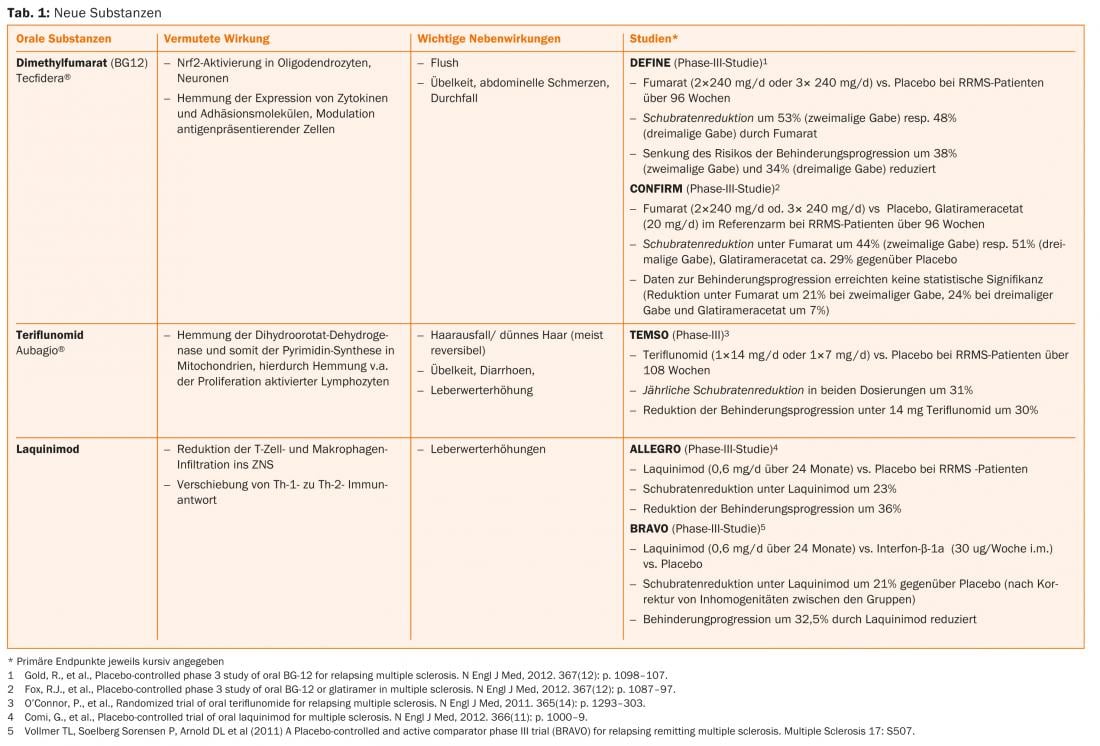

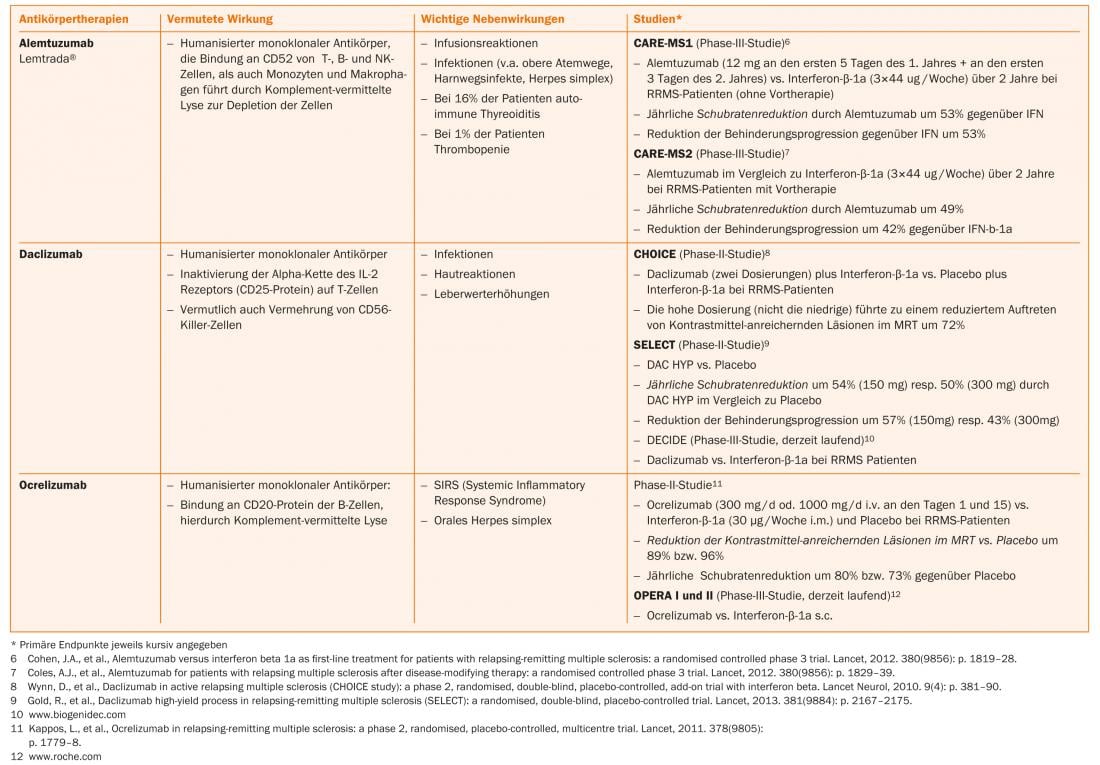

More recently, progress has been made in the treatment of CIS and RRMS. In addition to oral substances (such as fumaric acid, laquinimod, teriflunomide), antibody therapies (such as alemtuzumab, daclizumab, ocrelizumab) are also in phase II or III studies or some corresponding studies have already been completed.

Fumaric acid, teriflunomide and alemtuzumab are already approved in some countries, so that an expansion of the therapeutic options can also be expected in Switzerland in the near future (Tab. 1 and Fig. 1).

Current therapeutic options

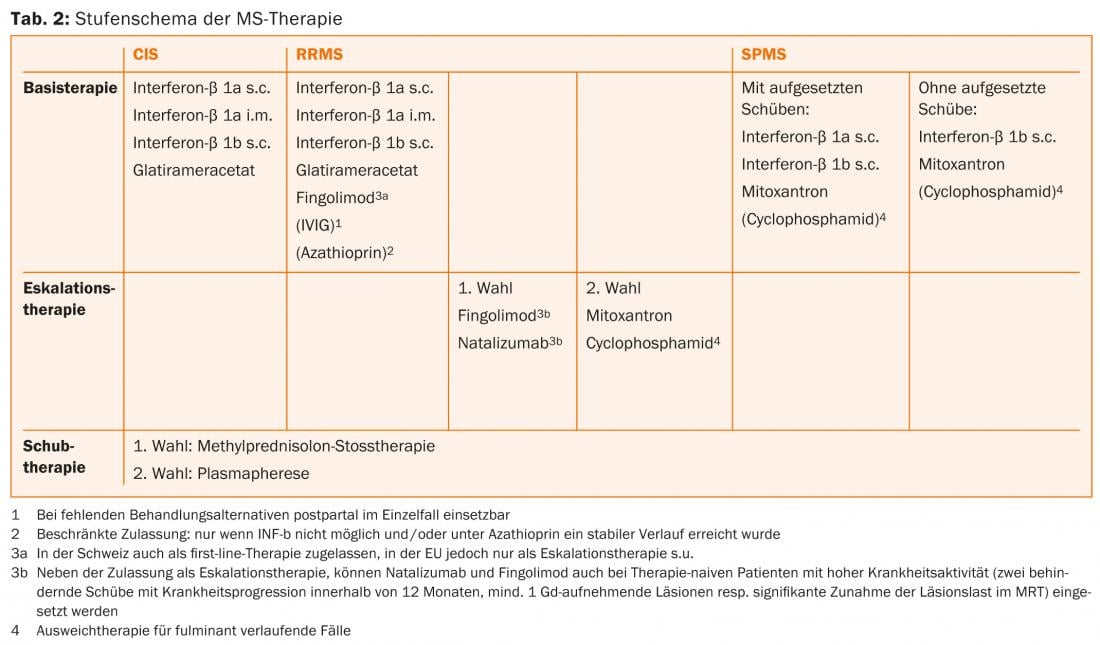

For the treatment of CIS and RRMS patients, beta-interferons (interferon-beta 1b s.c. [Betaferon®], interferon-beta 1a s.c. and i.m.) are available in the EU and Switzerland. [Betaferon®], interferon-beta 1a s.c. and i.m. [Rebif® and Avonex®] and glatiramer acetate s.c. [Copaxone®] have been approved [7, 8]. For these substances, which are usually injected by the patient himself, there are many years of extensive experience and they are characterized in particular by a favorable safety profile [9]. In 2011, fingolimod was additionally approved in Switzerland as first-line therapy for the treatment of RRMS [10]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examinations should be performed initially and regularly during the course of therapy to determine the initial situation and for subsequent therapy monitoring.

The interferons (IFN) used are recombinantly produced. Endogenous IFNs are integral components of the immune system that are important for the immune response to viral infections. The exact mechanism of action of IFN-β preparations in the treatment of CIS/RRMS has not yet been fully elucidated. Flu-like side effects are common, especially during the first few months of therapy, and can be alleviated by taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug or acetaminophen [11]. Local side effects such as pain, redness of the skin, lipoatrophy, and induration may occur at the injection sites [12, 13]. As an alternative to beta-interferons, the copolymer glatiramer acetate, which is comparable in efficacy, can be used, a heterogeneous mixture of synthetic polypeptides consisting of four amino acids, whose mechanism of action is also not fully understood [14]. Flu-like side effects are not relevant with this drug, but postinjection reactions with flushing symptomatology and local induration or lipoatrophy at the injection sites may occur [15].

In Switzerland, fingolimod (tablet) is additionally approved for first-line basic therapy of RRMS. Fingolimod is the first orally available, generally well tolerated, disease-modifying MS therapy that was superior to the comparator interferon-beta 1a i.m. in one of the pivotal studies [17]. Fingolimod binds as a non-selective high affinity antagonist to sphingosine-1-phosphate receptors (S1P-R) on lymphocytes, thereby preventing their emigration from secondary lymphoid organs. Redistribution of lymphocytes results in lymphopenia, and metabolism in the liver may result in elevated liver enzymes. Due to the expression of S1P receptors in the area of the cardiac conduction system, side effects such as bradycardia or a disturbance of the atrioventricular conduction may occur, especially during the first intake. For this reason, checks of blood pressure, pulse and ECG are necessary at the first administration as well as after breaks in therapy. Macular edema may occur as a rare complication [16]. Because of the effects on the immune system, patients whose skin type predisposes to malignancy should be examined dermatologically on a regular basis [17, 18]. In addition, viral infections in particular are favored. In patients who have not experienced chickenpox, anti-varicella zoster virus antibody titers should be determined before starting therapy. Seronegative patients should be vaccinated.

New substances such as alemtuzumab (infusion, only for patients with current disease activity), dimethyl fumarate (tablet) and teriflunomide (tablet) have already been approved for the treatment of RRMS in some countries and have been submitted for approval in Switzerland.

Escalation Therapy

Therapy escalation from first-line therapy to fingolimod (itself first-line in Switzerland, not in the EU) [16, 19] or natalizumab [20] may be considered if ≥1 relapse has occurred on baseline therapy in the previous year and there are ≥9 T2-hyperintense lesions or ≥1 acute, i.e., contrast-enhancing lesion on MRI. IFNs are mentioned as the appropriate basic therapy in the indications. However, current practice is to equally evaluate escalation in patients treated with glatiramer acetate or, in the case of escalation to natalizumab, fingolimod. Primary treatment with natalizumab or (in the EU, not restricted in Switzerland) fingolimod is indicated only for patients who have had ≥2 relapses with disability progression in the past year and who have ≥1 contrast-enhancing lesion or a “significant” increase in T2 lesion load detectable on cerebral MRI.

Natalizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody against the cellular adhesion molecule α4-integrin, which lymphocytes require to enter the CNS. In the pivotal trial, natalizumab reduced relapse rates by 68% compared with placebo and similarly demonstrated a good effect on disability progression and signs of disease activity on magnetic resonance imaging [20]. Natalizumab is administered by infusion every 28 days and is usually well tolerated. The use of this very effective drug is limited by the risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML). This opportunistic infection caused by the JC virus often leads to severe disabilities, and a lethal outcome is possible. There is no targeted treatment option for PML. Therefore, in PML, natalizumab is discontinued and washed out with plasmapheresis to restore immunocompetence as quickly as possible. Slightly more than half of MS patients and the corresponding healthy population are carriers of the JC virus. While JC-seronegative patients have a low risk of PML (approximately 1:10,000) [21], the risk in seropositive patients can increase up to approximately 1:89 for the third and fourth year if immunosuppressive therapy had been given in the past. Therefore, depending on the individual risk, careful counseling of patients about benefits and risks is necessary [22]. When switching from fingolimod to natalizumab, a washout period of approximately two months should be observed; at a minimum, it is necessary to wait for normalization of lymphocyte counts [23]. As reserve and second-line drugs, mitoxantrone, cyclophosphamide, or azathioprine [23] can be used in escalation therapy after careful review (Table 2). Other off-label therapies may be considered.

Finally, it should be mentioned that combinations of the above MS therapeutics are not approved.

Desire for children, pregnancy, breastfeeding

MS often affects young women. The question of treatment during childbearing, pregnancy and lactation is therefore relevant. The use of the teratogenic chemotherapeutic agents or immunosuppressants azathioprine, cyclophosphamide, and mitoxantrone is contraindicated. A washout period should also be observed with fingolimod before ending contraception, if possible. Glatiramer acetate was rated highest by the U.S. Food and Drug Agency (FDA) for risk when exposed during pregnancy because this drug was not teratogenic in animal studies and previous human data are also favorable [24]. Also, no teratogenicity has been observed for interferons and natalizumab in humans to date.

Although these data are not from controlled trials, consideration should be given to interrupting treatment with any of these drugs only when pregnancy occurs, taking into account the respective label. During pregnancy, when relapse activity is usually low, treatment is given only in rare exceptional cases. Treatment is also not usually given during breastfeeding, especially since many MS sufferers do not breastfeed in order to be able to start treatment again after giving birth, after which there is often a high level of disease activity.

Use of basic therapeutics in progressive forms

Effective treatment options with a clear effect for the progressive form of progression do not exist at present; rather, in addition to an individual, multimodal, symptomatic therapy, physiotherapeutic and rehabilitative measures are in the foreground. In SPMS, the option of using IFN-β-1b and, if mounted relapses are present, IFN-β-1a s.c. [25] is an option.

If a particularly aggressive course is present, the administration of mitoxantrone should be discussed [26]. Prior to this, a careful assessment of the risk-benefit ratio should be made, particularly because of the increased risk of leukemia [27] and cardiomyopathy and the toxic effect on gonadal function. The duration of therapy is limited by the total cumulative dose that can be applied (in Switzerland max. 100 mg/m2 body surface). This can be exceeded if necessary under careful control of cardiac function.

Conclusion

Early therapy of CIS/RRMS is important for disease progression. An increasing number of drugs are available for this purpose, which differ in terms of efficacy, safety, side effect profile and therapeutic comfort. The increasing choice of MS therapeutics offers the possibility of a more individualized therapy, adapted to the specific patient profile.

Helen Könnecke

PD Michael Linnebank, MD

Literature:

- Polman CH, et al: Ann Neurol 2011; 69(2): 292-302.

- Weinshenker BG, et al: Brain 1989; 112(Pt1): 133-146.

- Weinshenker BG: Semin Neurol 1998; 18(3): 301-307.

- Miller DH, et al: Mult Scler 2008; 14(9): 1157-1174.

- Weinshenker BG, et al: Brain 1989; 112(Pt 6): 1419-1428.

- Hirst C, et al: J Neurol 2008; 255(2): 280-287.

- Buttmann M, Rieckmann P: Expert Rev Neurother 2007; 7(3): 227-239.

- Comi G, et al: Ann Neurol 2011; 69(1): 75-82.

- Reder AT, et al: Neurology 2010; 74(23): 1877-1885.

- www.swissmedic.ch.

- Hartung HP, et al: Neurologist 2013; 84(6): 679-704.

- Nikfar S, Rahimi R, Abdollahi M: Clin Ther 2010; 32(11): 1871-1888.

- Plosker GL: CNS Drugs 2011; 25(1): 67-88.

- O’Connor P, et al: Lancet Neurol 2009; 8(10): 889-897.

- Ford C, et al: Mult Scler 2010; 16(3): 342-350.

- Cohen JA, et al: NEJM 2010; 362(5): 402-415.

- Comi G, et al: Mult Scler 2010; 16(2): 197-207.

- Kappos L, et al: NEJM 2006; 355(11): 1124-1140.

- Kappos L, et al: NEJM 2010; 362(5): 387-401.

- Polman CH, et al: NEJM 2006; 354(9): 899-910.

- Bloomgren G, et al: NEJM 2012; 366(20): 1870-1880.

- www.biogenidec.ch.

- DGN guideline on the diagnosis and therapy of MS. Diener HC, Weimar C (eds.): Guidelines of the German Society of Neurology Thieme Verlag: Stuttgart 2012, 430-475.

- Salminen HJ, Leggett H, Boggild M: J Neurol 2010; 257(12): 2020-2023.

- Kappos L, et al: Neurology 2004; 63(10): 1779-1787.

- Hartung HP, et al: Lancet 2002; 360(9350): 2018-2025.

- Martinelli V, et al: Neurology 2011; 77(21): 1887-1895.

InFo Neurology & Psychiatry 2013; 11(6): 13-20.