“The lower the better” – the approach to lower cholesterol levels as much as possible in patients at cardiovascular risk is more relevant than ever, according to the update of the Swiss AGLA guidelines and the new ESC/ESA guidelines, respectively. In fact, a 1 mmol/l reduction in LDL-C reduces the risk of cardiovascular events by one-fifth. However, such LDL reductions are difficult in some patients. In addition, the questions arise: when to refer to the specialist and when to do a genetic workup?

“The lower the better” – the approach to lower cholesterol levels as much as possible in patients at cardiovascular risk is more relevant than ever, according to the update of the Swiss AGLA guidelines and the new ESC/ESA guidelines, respectively. In fact, a reduction in LDL-C of 1 mmol/l reduces the risk of cardio-vascular events by one-fifth. However, such LDL reductions are difficult in some patients. In addition, the questions arise: when to refer to the specialist and when to do a genetic workup?

Dyslipidemias are among the leading causes of cardiovascular disease. The focus is particularly on LDL cholesterol (“low density lipoprotein cholesterol”). Several studies over the past decades clearly show that lowering LDL-C concentrations is associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular events [1,2]. The causes of dyslipidemias are diverse. According to the Swiss Heart Foundation, familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) affects about one in 200 people in this country [3]. Thus, FH is present in approximately 30% of younger patients with coronary artery disease (CAD) or myocardial infarction [4]. In addition, lifestyle and diseases such as hypothyroidism, liver disease, obesity, chronic renal insufficiency, insufficiently controlled diabetes mellitus or the side effects of certain drugs (e.g. antivirals) are known to have a considerable influence on changes in fat metabolism. These risk factors lead to the fact that today about every third person in Switzerland has an unfavorable lipid profile [5].

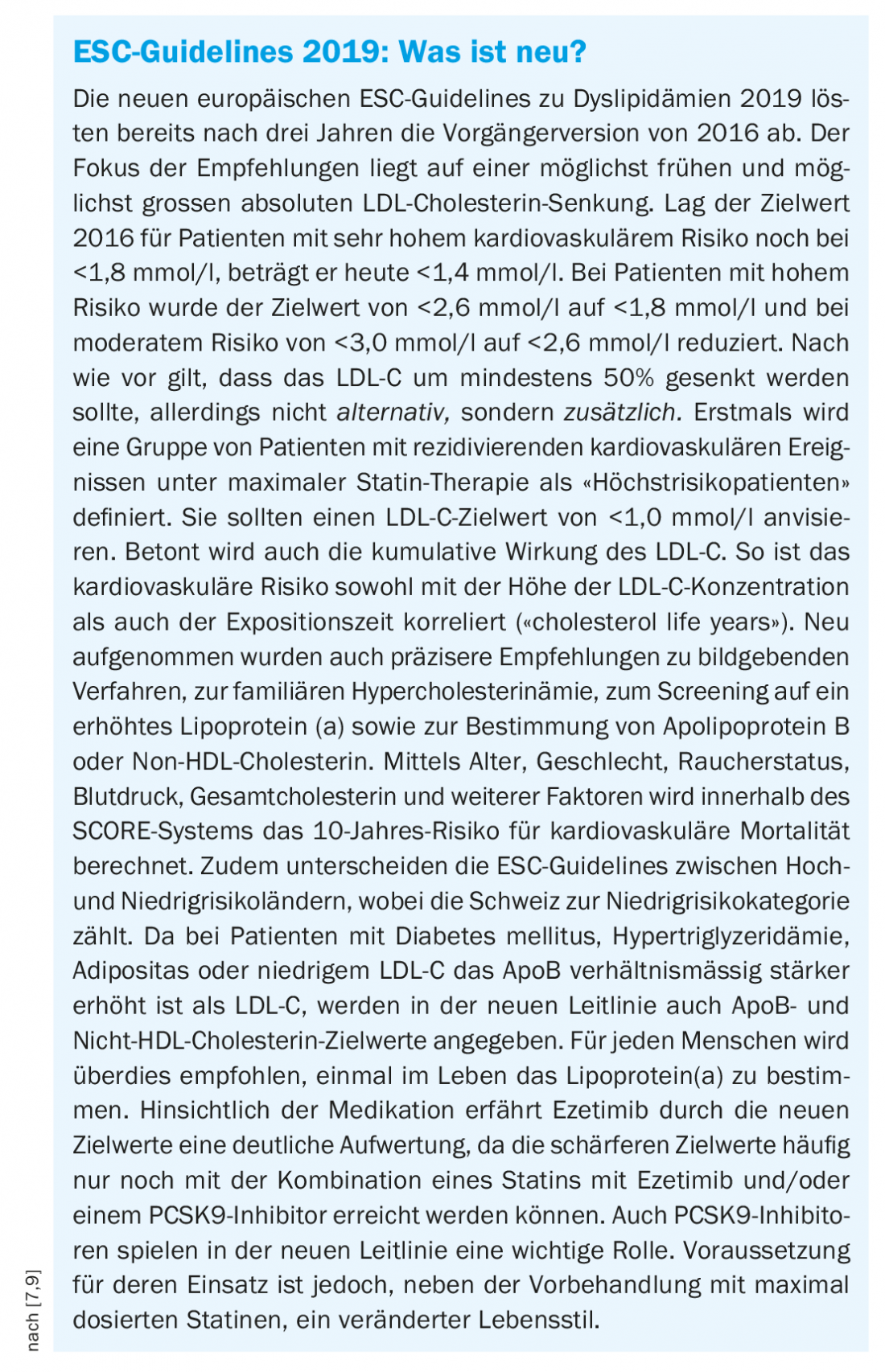

Although only a few years have passed since the publication of the last European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) guidelines on the treatment of dyslipidemia in 2016, a large body of new scientific evidence and the development of new therapeutic options necessitated an update of the guidelines [6]. These new “ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias” presented in 2019 were reviewed and adapted the following year by the Lipids and Atherosclerosis Working Group (AGLA) with a view to their application in Switzerland [7,8]. The goal of this summary is to inform primary care physicians about the updated guidelines and to provide guidance on when to refer which patients to a specialist.

Risk assessment

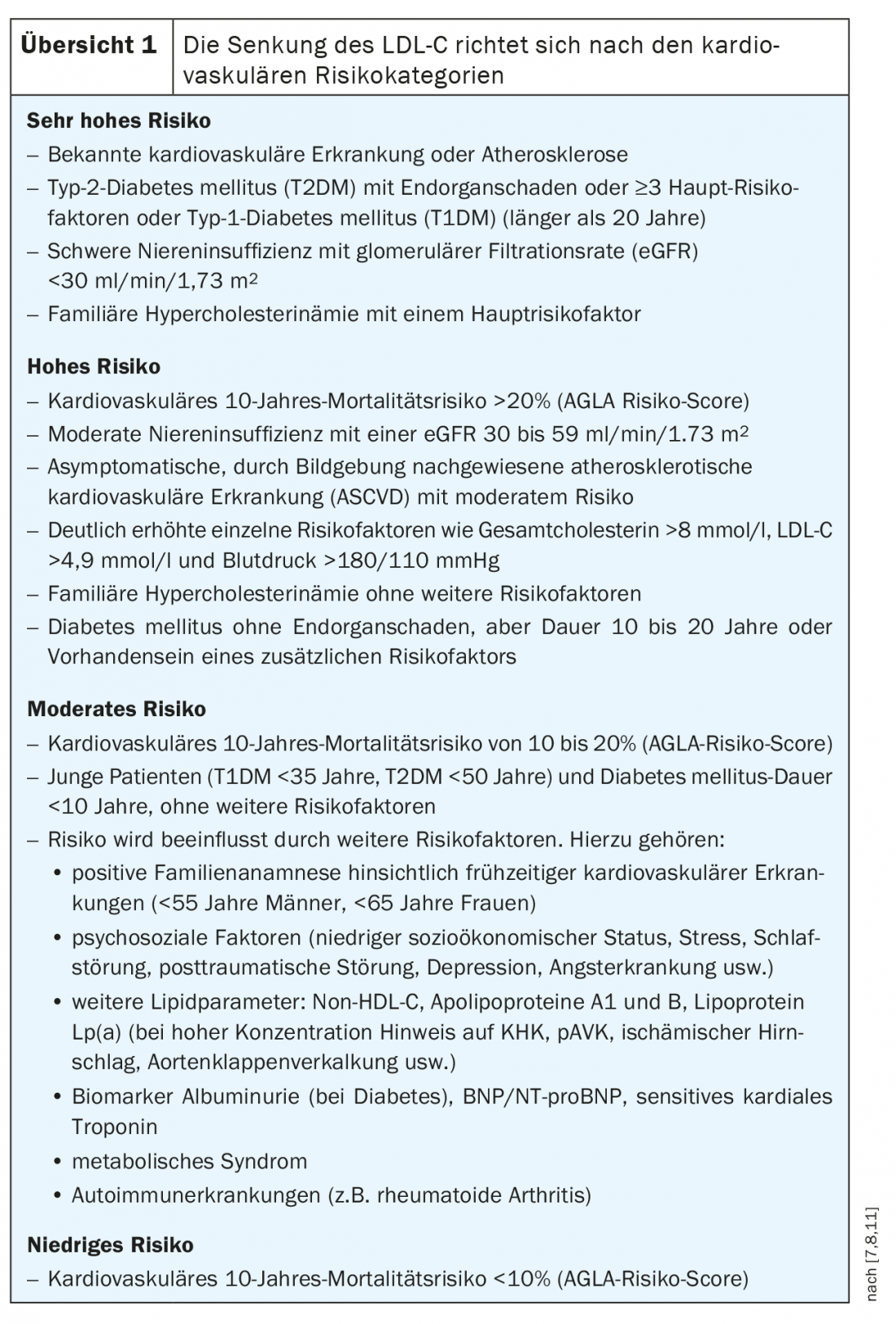

There is no doubt that elevated choles-te-rin levels are associated with increased cardiovascular risk. The evaluation of risk factors is a central component of the risk calculation. For example, not only the level of lipids is crucial, but also the duration of exposure [6]. According to the ESC/EAS guidelines, four different risk categories are classified, namely very high, high, moderate, and low risk (Overview 1).

In Switzerland, the AGLA risk calculator has become established for calculating individual risk. It can be used to easily calculate online the absolute risk over ten years for a fatal coronary event or nonfatal myocardial infarction (www.agla.ch/de/rechner-und-tools/agla-risikorechner) [8]. The AGLA calculator incorporates parameters such as age, family history, smoking, blood pressure, LDL cholesterol, HDL cholesterol or triglyceride levels. However, physical activity, radiotherapy, etc. are not taken into account.

The ESC/EAS-SCORE can also be used to estimate the 10-year risk of cardiovascular mortality (www.scores.bnk.de/esc.html). Switzerland is considered a region with a low cardiovascular risk, and the “low-risk ESC-SCORE variant” is used accordingly.

For primary prevention, the AGLA recommends initial risk assessment in asymptomatic men older than 40 years and women older than 50 years. Low-risk patients should be re-evaluated every five years, and moderate-risk patients should be re-evaluated every two to five years. For individuals who are already at high or very high risk at initial assessment, estimation with a risk calculator is not necessary because these patients are automatically classified as high-risk. This applies to:

- Documented cardiovascular disease (e.g., myocardial infarction or acute coronary syndrome, 2-disease with at least. 50% stenosis on cardiac CT, ischemic stroke, peripheral arterial disease (PAVD), or history of coronary/arterial revascularization).

- Diabetes mellitus with end-organ damage, long disease duration, or at least 3 risk factors

- moderate to severe renal insufficiency (KDIGO grade ≥3).

- Pronounced individual risk factors (LDL-C >4.9 mmol/l, total cholesterol >8 mmol/l, blood pressure >180/110 mmHg)

- familial hypercholesterolemia

- strong lipoprotein Lp(a) elevation

Risk modifiers

For patients at low and especially moderate risk, additional risk assessment criteria were newly introduced as a potential complementary tool. Such “risk modifiers” may help adjust cardiovascular risk estimates. Patients who are actually in a lower risk category may then be placed in a higher risk level. Such modifiers include:

- Social deprivation, psychosocial stress, vital exhaustion, severe psychiatric illness.

- Noninvasive cardiovascular imaging: coronary artery calcium (CAC) score measurement on cardiac CT (CAC score, Agatston score), femoral artery and carotid artery sonography for plaque detection (IIbB).

- Positive family history of early cardiovascular disease (men <55 years, women <60 years).

- Physical inactivity, obesity (measured by body mass index or abdominal girth measurement).

- Chronic immune-mediated inflammatory disease

- Treatment for HIV infection

- Atrial fibrillation

- Left ventricular hypertrophy

- Chronic renal failure

- Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome

- Non-alcoholic fatty liver

- Lipoprotein Lp(a)

LDL-C target values

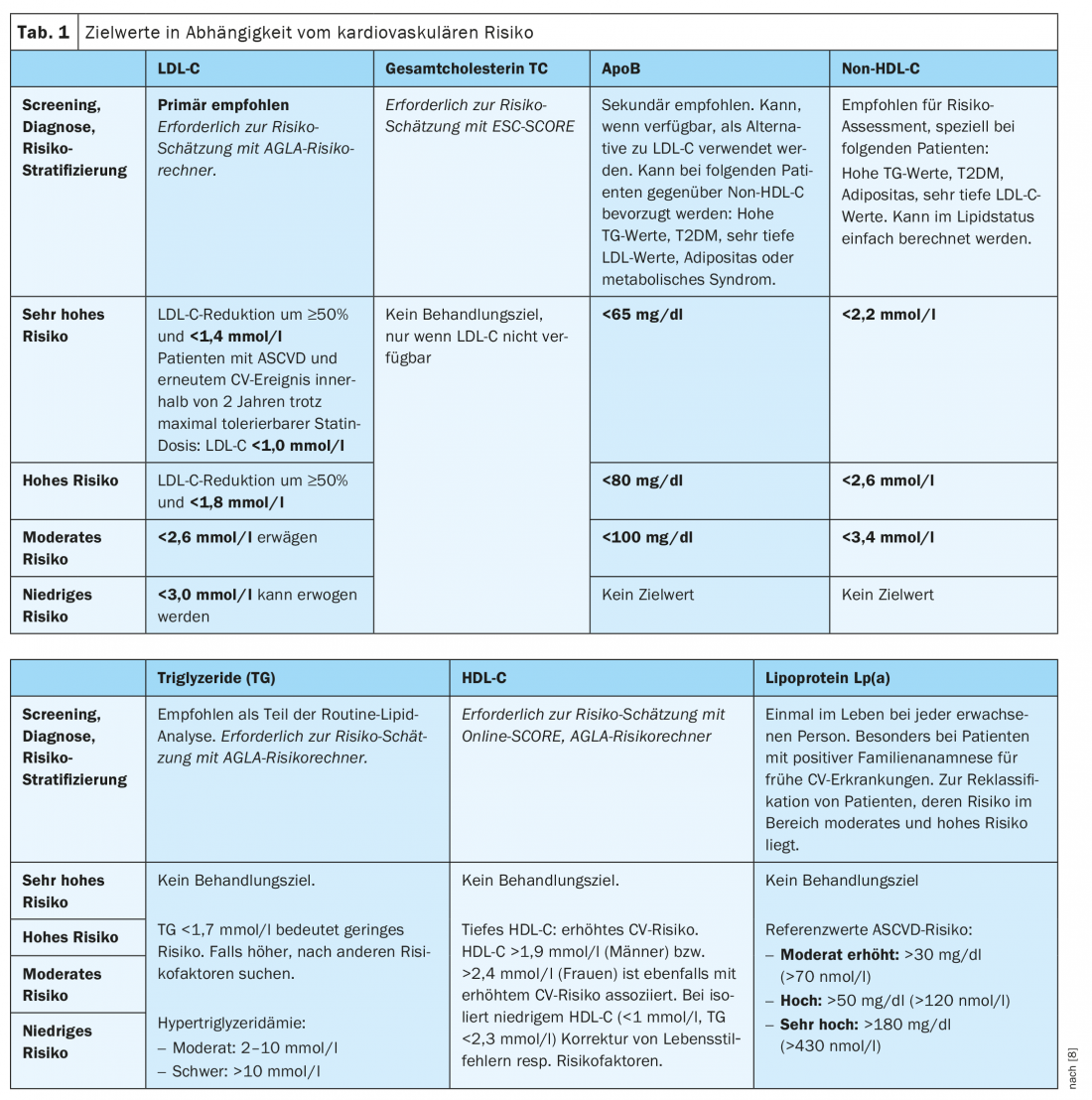

There is a significant association between LDL cholesterol lowering and cardiovascular risk reduction [10]. For this reason, the new ESC guidelines (and correspondingly, the current AGLA guidelines) went beyond the recommendations of past guidelines in formulating the new LDL-C-lowering targets. In principle, LDL-C should be lowered as low as possible (“the lower the better”), especially in the case of high and very high risk. The higher the cardiovascular risk, the lower the target values (Table 1) .

In patients at very high risk, LDL-C reduction of 50% and a target LDL-C level of <1.4 mmol/l should be aimed for. In addition to 50% reduction, a target value of <1.8 mmol/l is recommended for high risk and <2.6 mmol/l for moderate risk. Finally, a low-risk level of <3.0 mmol/l can be targeted. Patients with FH with ASCVD or any other risk factor should be considered at very high risk (see below). According to the AGLA, the lipid status of nonfasting plasma is sufficient for assessment in most cases. However, fasting blood collection is recommended in the following situations:

- Metabolic syndrome

- Non-fasting triglycerides >5 mmol/l

- Known hypertriglyceridemia

- After hypertriglyceridemia induced pancreatitis.

- Before starting drug therapy with severe hypertriglyceridemia as a possible side effect.

- When additional analyses are required that must be determined fasting, e.g. fasting glucose, therapeutic drug monitoring.

Familial hypercholesterolemia

If the lipid profile shows significant disturbances, FH may also be present. In the case of genetically strongly elevated LDL cholesterol, affected individuals have a much greater cardiovascular risk than patients with acquired LDL at the same level [8]. Thus, in FH, the 10-year risk of myocardial infarction without treatment is over 50%. Indications of FH for adults include CHD in under 55-year-old men or under 60-year-old women. In addition, clarification is recommended for high cholesterol levels, namely total cholesterol ≥8mmol/l or LDL ≥5.0 mmol/l or triglycerides ≥5.0 mmol/l (children/adolescents correspondingly lower). Premature atherosclerosis or, in those younger than 45 years, tendon xanthomas or arcus cornealis, as well as genetic hyperlipidemia in other family members, could also indicate FH. If FH is suspected, this should be clarified according to the “Dutch Lipid Clinic Network Criteria” (www.agla.ch/de/rechner-und-tools/agla-fh-rechner). If the suspicion is confirmed, it should be treated as “high risk” and with an additional risk factor as “very high risk”. FH should be diagnosed clinically if possible and confirmed genetically, and family screening is also indicated in patients with FH. If the mutation is detected, therapy adherence is often improved.

Therapy

The treatment of dyslipidemia depends on the overall cardiovascular risk and the LDL target levels for patients based on this risk. The basis of such therapy is lifestyle change, especially with dietary adjustment, reduction of alcohol consumption, more exercise, weight loss and smoking cessation. If lipid reduction is required in addition to achieving the therapy goal according to the risk category, statins are the drugs of first choice. This means that in the first stage, highly effective statins are used at the maximum tolerable dose. If the target values are still missed, combination with the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe is recommended. If there is statin intolerance, ezetimibe should also be considered. A PCSK9 inhibitor may be used in addition to ezetimibe.

If patients at very high risk do not achieve their therapeutic goal despite maximum-dose statin plus ezetimibe, additional treatment with a PCSK9 inhibitor can be used in primary prevention. A combination with such a PCSK9 antibody can also be considered for patients at very high risk in secondary prevention, namely when the therapy target is missed despite maximum tolerable statin plus ezetimibe. For patients with FH at very high risk and failed treatment with highest-dose statin plus ezetimibe, a combination with a PCSK9 inhibitor is also suggested. In the future, other compounds will become available, such as bempedoic acid (ATP citrate liase inhibitor, effective only in the liver), includeisiran (an siRNA molecule that inhibits PCSK9), or ANGPTL3 antibodies in patients with high triglycerides.

The most important drugs for lipid lowering

With intensive therapy with statins, it is possible to reduce LDL concentrations by more than 50%, and with moderate therapy by more than 30 to 50%. The intensity of this reduction depends on the one hand on the statins used (atorvastatin, rosuvastatin and pitavastatin are considered potent statins), and on the other hand on the dosage and the genetic predisposition of the patient. For example, a large meta-analysis showed that lowering LDL-C by 1 mmol/l reduced the relative risk of cardiovascular events by 22% over five years [2]. Statins also reduce triglycerides by 10 to 20% but increase HDL only slightly (1 to 10%). The concentration of Lp(a), on the other hand, is not or only very slightly affected. Side effects of statin treatment may include myopathy, myositis, and rhabdomyolysis. Such muscle symptoms usually begin a few weeks after the start of therapy. In addition, especially in elderly patients, the risk of developing type 2 diabetes mellitus is slightly increased with high-dose statins [11]. Whether the risk of hemorrhagic stroke also increases slightly has not yet been proven beyond doubt. Care should be taken with interactions. Some statins react with certain drugs, such as immunosuppressants, HIV protease inhibitors, macrolides, azole antifungals, benzodiazepines, or calcium antagonists.

Cholesterol absorption inhibitors are also important tools for blood lipid reduction. Ezetimibe blocks the absorption of cholesterol in the intestine, reducing LDL levels by about 18.5%. Ezetimibe acts via Niemann-Pick C1-like protein 1 (NPC1L1), but it does not decrease absorption of fat-soluble foods.

Triglycerides are also decreased, by 8%, whereas there is a minimal increase in HDL [12]. The combination of ezetimibe with statins has been shown to further reduce cardiovascular events. The most common side effects of such combination therapy are headache, muscle pain, and elevation of transaminases GOT and GPT.

Lowering the concentration of PCSK9 (proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9) promotes the expression of LDL receptors and thus the uptake of LDL into liver cells. This leads to a significant reduction of LDL-C levels by about 60%, and in combination with maximum-dose statins by up to 73% [6]. The concentration of triglycerides and Lp(a) is also reduced by around a quarter, while HDL levels increase slightly. PCSK9 inhibitors (evolocumab, alirocumab) show a significant reduction in cardiovascular risk due to these effects. They are indicated in Switzerland for patients at very high cardiovascular risk whose dietary changes and LDL treatment with statins at the maximum tolerated dose (with or without ezetimibe) have failed to achieve target levels. In addition, arterial blood pressure must be controlled and, in the case of diabetes mellitus, the HbA1c value must be <8%, and nicotine abstinence must be aimed for. Obtaining a cost consultation from the health insurer is mandatory.

For secondary prevention, the following are eligible for treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors: high-risk patients with atherosclerotic ischemic cardiovascular events and an LDL-C of >2.6 mmol/l, adults with heterozygous FH, and, for evolocumab, adults and adolescents aged 12 years and older with homozygous FH. In primary prevention, PCSK9 inhibitors are indicated in adult and adolescent high-risk patients aged 12 years and older with severe heterozygous or homozygous FH and an LDL-C of >5.0 mmol/l. There is also an indication for patients with severe heterozygous FH, an LDL-C of >4.5 mmol/l, and at least one of the following risk factors: diabetes mellitus, Lp(a) >120 nmol/l, or severe hypertension.

Diagnosis and initial prescription as well as regular monitoring must be performed by a specialist FMH in angiology, diabetology/endocrinology, cardiology, nephrology, neurology or by designated hypercholesterolemia experts. Treatment with PCSK9 inhibitors may be continued only if successful. This means that, at follow-up within six months of treatment initiation, LDL-C should have been reduced by at least 40% from baseline or an LDL of <1.8 mmol/l should have been achieved on maximally intensified lipid-lowering therapy. This does not apply to individuals with homozygous FH.

Take-Home Messages

- LDL-C is one of the major causes of the development of cardiovascular disease.

- Patients at very high cardiovascular risk should be treated intensively with a 50% reduction in LDL-C and a target LDL-C level of <1.4 mmol/l, and patients at high risk should also be treated with a 50% reduction and a target level of <1.8 mmol/l. It should be noted that the duration of exposure to hypercholesterolemia is also critical.

- If target levels are not achieved with statins and ezetimibe at the maximum tolerable dose for at least three months, PCSK9 inhibitors should be used in patients at very high cardiovascular risk.

- Patients with familial hypercholesterolemia and at least one cardiovascular risk factor are considered high-risk. They should also be treated intensively (statins, ezetimibe, and PCSK9 inhibitors) with an LDL-C >5.0 mmol/l or >4.5 mmol/l plus other risk factors.

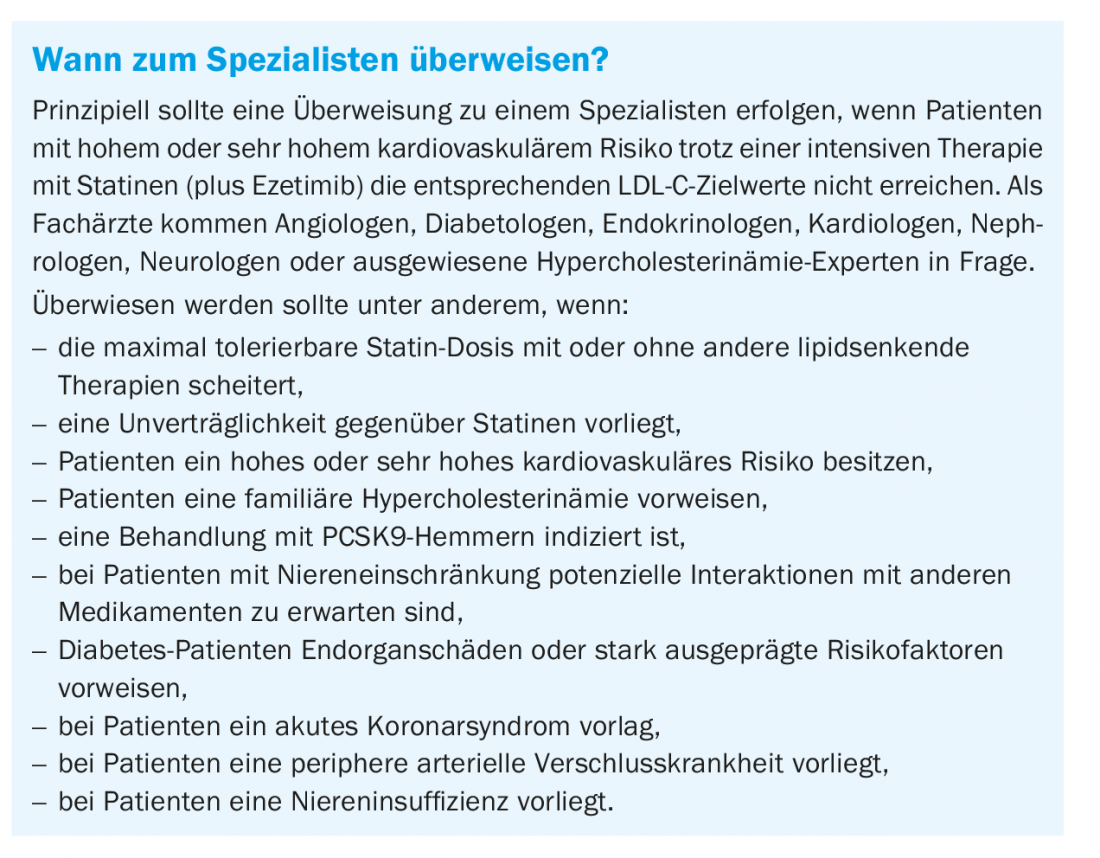

- Referral to a specialist should be made if intensive LDL therapy fails, if patients are at high or very high risk or have familial hypercholesterolemia, or if certain cardiovascular risk factors are present.

- In familial hypercholesterolemia, family screening is mandatory and genetic workup is recommended.

Literature:

- Carballo D, Mach F: Intensive LDL-cholesterol lowering and inhibition of inflammation to further reduce cardiovascular risk. Cardiovascular medicine 2018; 21(12): 310-315.

- Baigent C, et al: Cholesterol Treatment Trialists Collaboration: Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a metaanalysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet 2010; 376: 1670-1681.

- www.swissheart.ch/de/herzkrankheiten-hirnschlag/erkrankungen/familiaere-hypercholesterinaemie.html.

- Rodondi N: Should patients be screened for familial hypercholesterolemia in the physician’s office? Switzerland Med Forum 2014; 14(19): 377.

- www.swissheart.ch.

- Riesen WF et al: New ESC/EAS dyslipidemia guidelines. Swiss Medical Forum 2020; 20(9-10): 140-148.

- Mach F, et al: 2019 ESC/EAS Guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias: lipid modification to reduce cardiovascular risk. European Heart Journal 2019; doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz455.

- AGLA: Prevention of Atherosclerosis Focus on Dyslipidemia 2020; www.agla.ch.

- Weingärtner O, et al: Commentary on the ESC/EAS guidelines (2019) on the diagnosis and treatment of dyslipidemias. Cardiology 2020; 14: 256-266.

- McCormack T, et al: Very low LDL-C levels may safely provide additional clinical cardiovascular benefit: the evidence to date. Int J Clin Pract 2016; 70(11): 886-897; doi: 10.1111/ijcp.12881.

- Sattar N, et al: Statins and risk of incident diabetes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomised statin trials. 2010 Feb 27; 375(9716): 735-742.

- Pandor A, et al: Ezetimibe monotherapy for cholesterol lowering in 2,722 people: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Intern Med 2009; 265(5): 568-580; doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.02062.x.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2021; 16(10): 9-13