Eating disorder therapy includes both psychological and somatic treatment. To avoid dropouts, case management must be established early on.

Eating disorders can be characterized by food refusal, but also by excessive food intake. Mostly female, patients with anorexia (AN) strive for an extremely thin body and refuse to eat a normal, healthy diet. Patients with bulimia nervosa (BN) have great fear of gaining weight, but food refusal tends to be moderate, except for periods of intermittent fasting. For patients with BN, recurrent binge eating followed by measures to prevent weight gain (e.g., vomiting) are central to the disorder. 66% of patients suffering from binge eating syndrome (BES) are male. Similar to bulimia, these patients show episodic, binge-like eating behavior, but do not take any countermeasures to prevent weight gain. Patients suffering from BES often show significant overweight or obesity. This poses a particular challenge to therapy.

Eating disorders, while less common than affective disorders, have great clinical and societal relevance. Patients are usually in adolescence or young adulthood, so that these serious diseases, in addition to the physical consequences, very particularly affect the educational and professional career. Anorexia in particular is a difficult-to-treat mental disorder that often becomes chronic and can also take a life-threatening course. The 12-year lethality is about 10%, higher than for depression or schizophrenia.

The direct and consequential costs caused by eating disorders are very high. AN is estimated to cost 195 million euros per year and BN 124 million euros per year in treatment and lost productivity costs.

Anorexia (Anorexia)

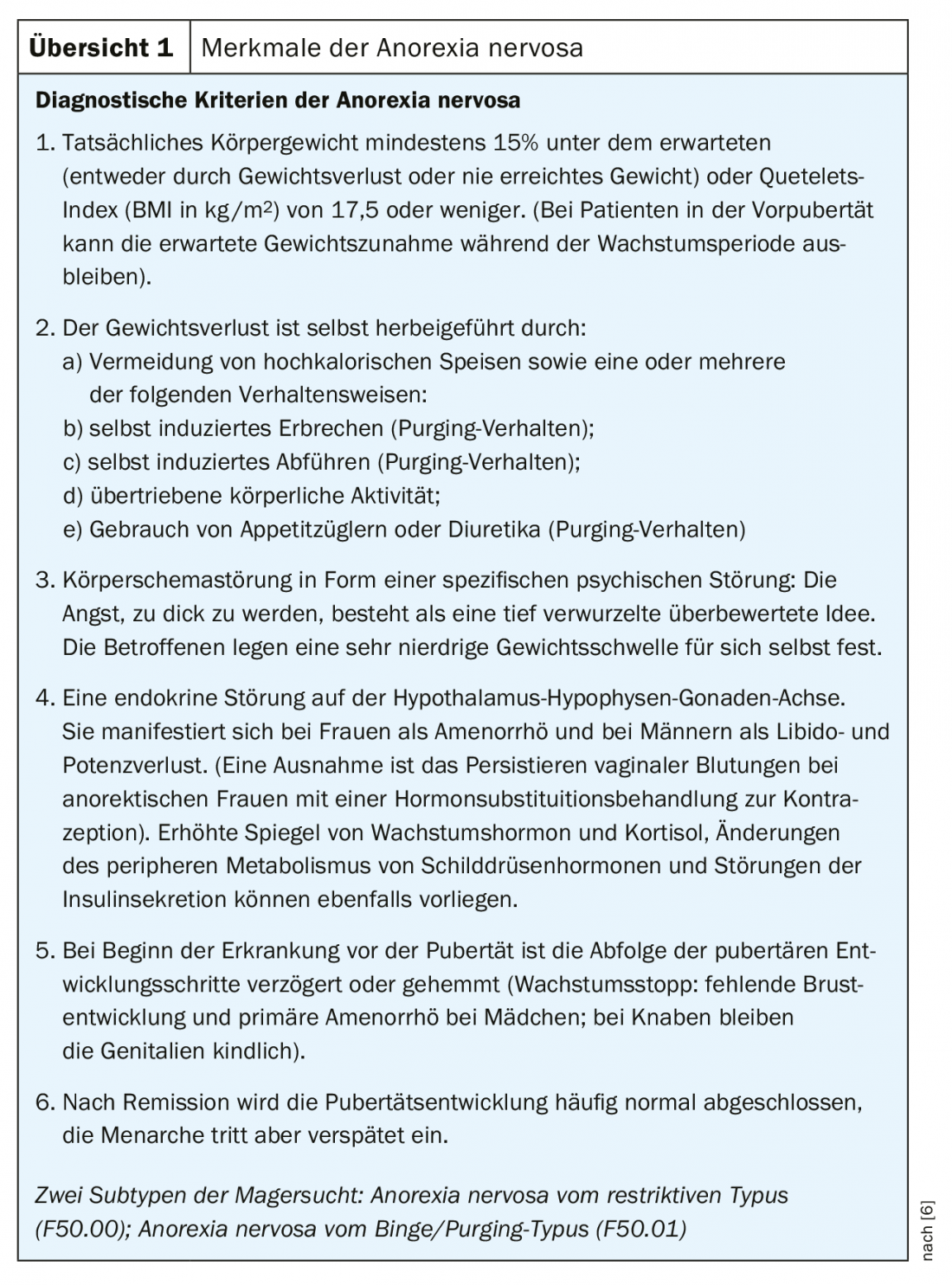

In this form of the disease, the affected persons starve themselves intentionally, resulting in severe underweight. Nevertheless, there is a massive fear of weight gain on the part of the patient because the body schema is disturbed and the underweight is not perceived. If laxatives and diuretics are also used, it is called the purging form of anorexia. Extreme weight loss through pure food restriction and excessive exercise is called the Non Purging form. Weight reduction leads to a change in the entire hormone balance and to an increase in cortisone, so that growth disorders, infertility and osteoporosis can occur. The high amount of cortisone affects other neurotransmitters active in the brain. The patients are physically and mentally very capable in the short term, but severely limited in their perception of the disease. In the long term, mental and physical functioning is reduced. Diagnostic criteria are

Overview 1.

Binge eating disorder (bulimia)

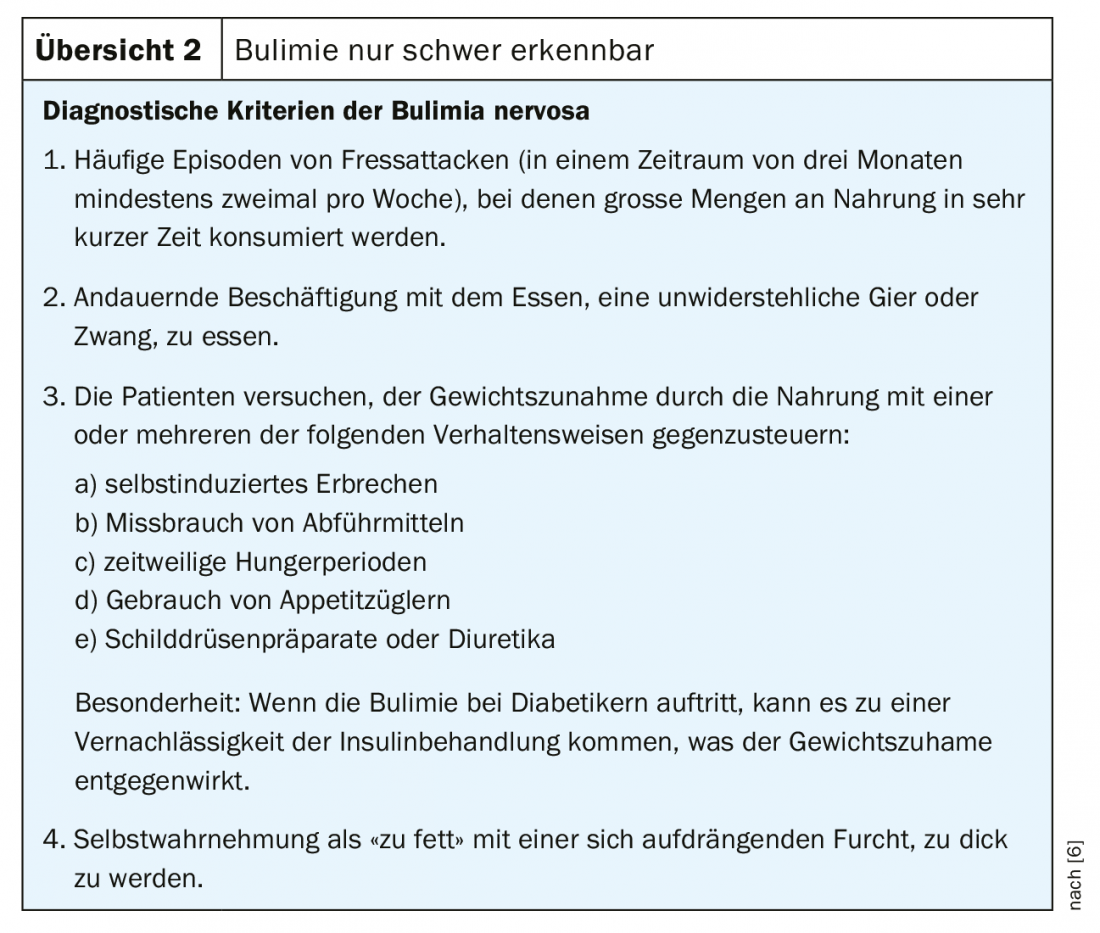

In contrast to anorexia, where the main symptom of being underweight is recognized with just a few glances, patients with bulimia appear inconspicuous at first because they are often of normal weight. Bulimia is characterized by typical bouts of ravenous hunger with loss of control. In this situation, the phase of loss of control, large amounts of food are devoured secretly and hastily, which are highly caloric. In some cases, up to 10,000 kcal are consumed during such a meal. Interrupting the eating process is not possible for the patients. Subsequently, vomiting is done to compensate in order to be able to maintain the weight (usually directly after the meal). In maximal manifestations of bulimia, the entire daily structure may consist of cycles of eating and vomiting. Financial difficulties and problems associated with obtaining food are not uncommon. Similar to anorexia, bulimia nervosa involves great fears of gaining weight and a pronounced body schema disorder. The disease is characterized by secrecy and shame, so that bulimia often remains undetected for years in the patients’ environment. Vomiting can lead to swelling of the salivary glands, shifting of blood salts, tooth enamel destruction, and scarring of the esophagus [1]. Overview 2 summarizes aspects of bulimia nervosa.

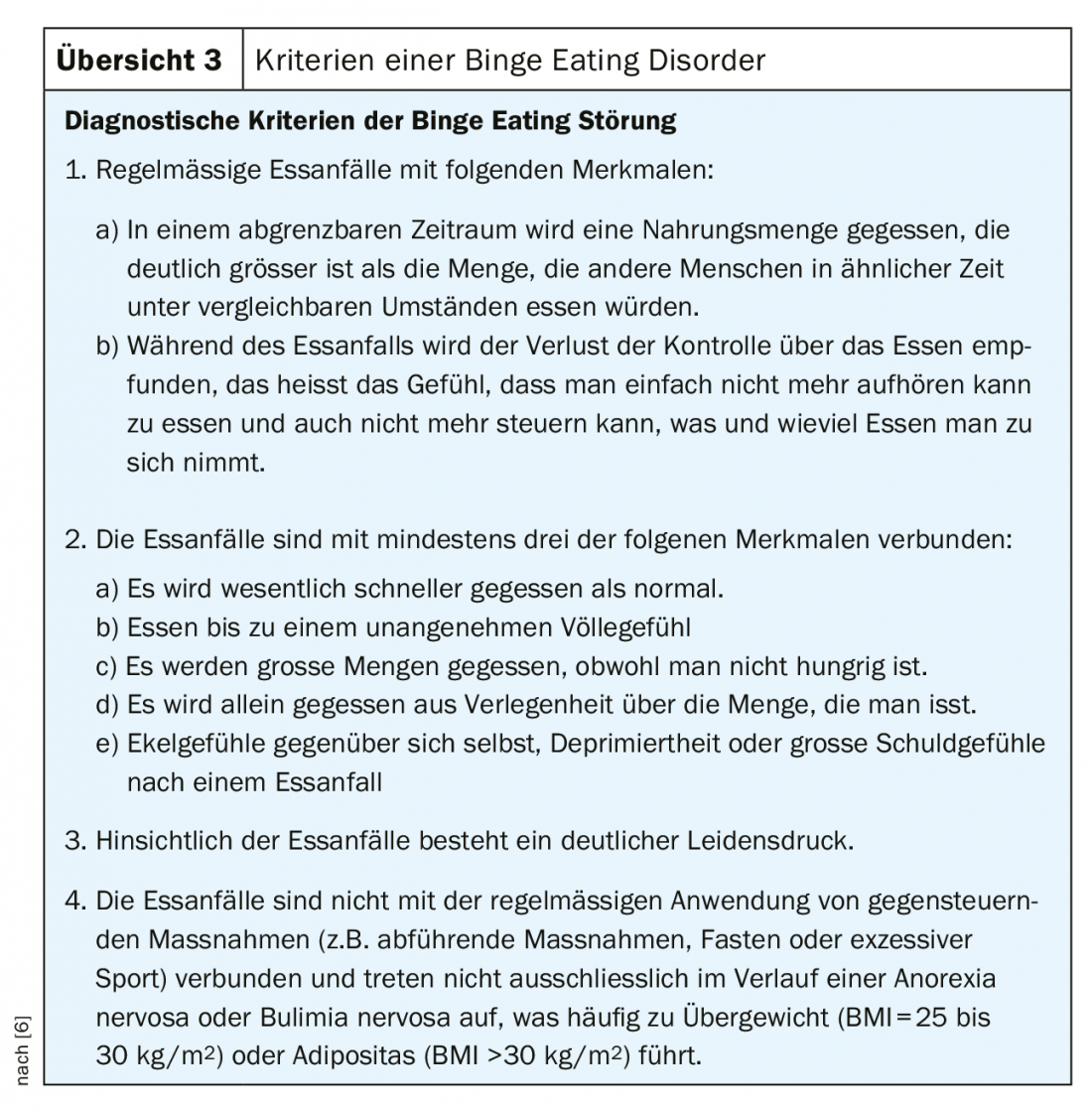

Binge Eating Disorder

Eating disorders in which patients have binge eating episodes without taking measures to counteract weight gain are grouped under the term binge eating disorder. This form has only been known as a separate clinical picture for a few years and has some parallels to bulimia. Mainly adults are affected. However, this eating behavior can also be observed in adolescents (overview 3).

Atypical eating disorders: The majority of patients requiring treatment are atypical or nonspecific eating disorders (NNB) when the diagnostic criteria based on ICD-10 or DSM-IV are consistently applied. However, this group tends to be neglected in the creation of eating disorder programs or research, so knowledge about atypical or unspecified eating disorders is very limited. The ICD-10 recognizes atypical anorexia (F50.1), atypical bulimia (F50.3), binge eating and vomiting in other mental disorders (F504 and F50.5), other eating disorders (F50.8), and unspecified eating disorders (F50.9). There is no more detailed description. In DSM-IV, in addition to anorexia and bulimia, there is only the residual category of unspecified eating disorder (NNB). Subsyndromal manifestations of the classic eating disorders and new syndromes, such as chewing-spitting syndrome or binge-eating disorder, for which formulated criteria already exist, are listed.

Subsyndromal eating disorders: These are manifestations of disordered eating in which one (or in special cases several) main symptom of the diagnosis is missing. In anorexia, for example, this would be the absence of amenorrhea; in bulimia, the absence of a pathological fear of weight gain. The definition based on a list of characteristics is particularly clear for anorexia with the following examples: many patients state through distortion or denial that they think they are too slim and want to gain weight. With this seemingly normal behavior, an atypical form of anorexia would already have to be diagnosed. Menstruation may persist when taking contraceptives; again, atypical anorexia would need to be diagnosed. However, there is sufficient evidence that patients with subsyndromal AN or BN do not differ from patients presenting with the full-blown disorder – neither in the extent of general psychopathology, eating disorder-specific problems, nor in the course or prognosis of the disorder [2]. In the presence of a subsyndromal manifestation of anorexia or bulimia, treatment is thus analogous to the treatment of the full syndrome of the corresponding disorder.

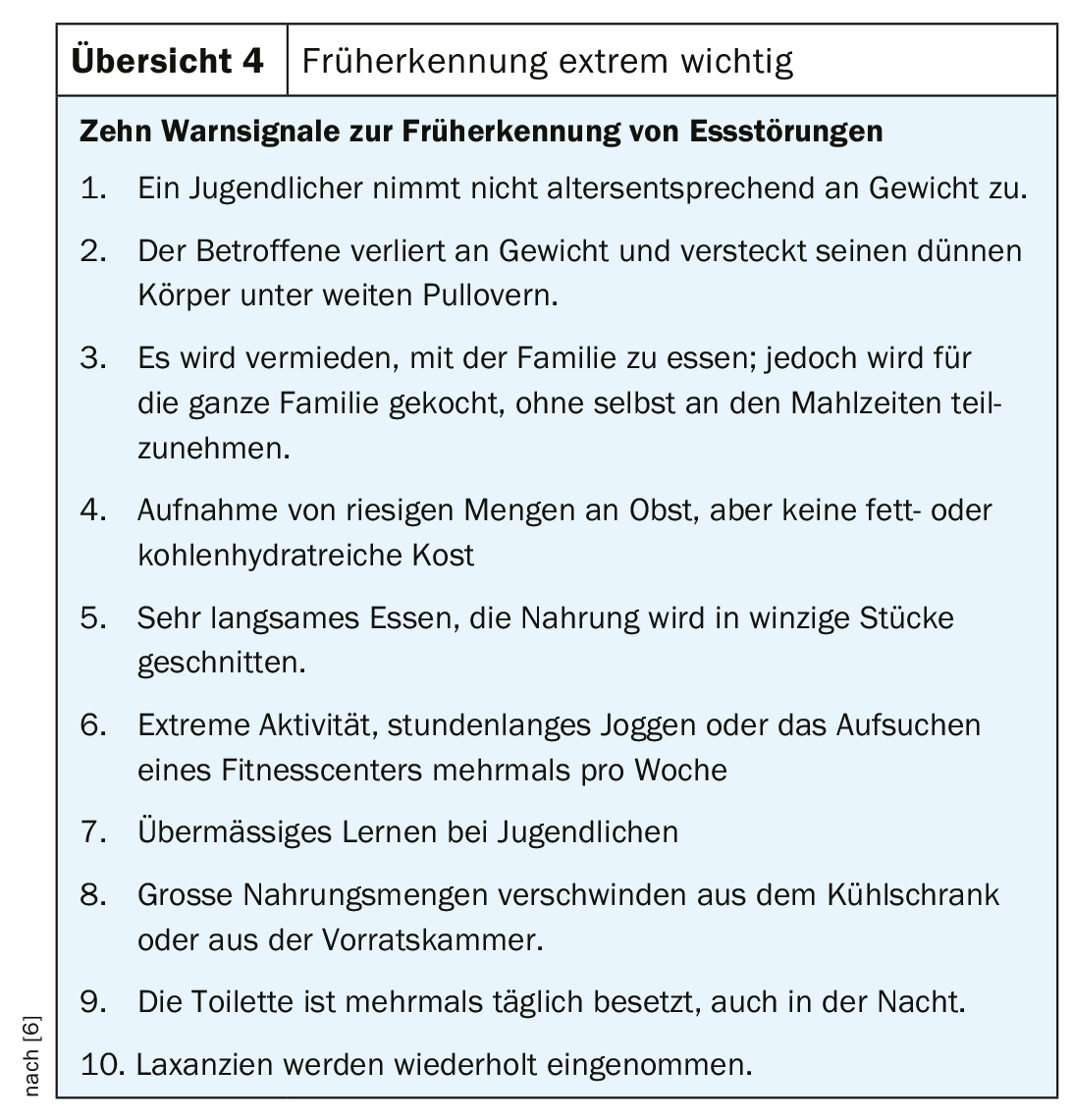

Early detection

Eating disorders in adolescents are often misrecognized. Knowledge of the clinic of eating disorders, especially anorexia, is still insufficient. Especially the attending physicians or school physicians, but also the sports teachers have a key function here in order to be able to initiate an early therapy. According to Krawautz [3], the specific symptoms are perceived in only 8% of typical cases and are instead misinterpreted as organic disease. In contrast, the accompanying psychosomatic problems and depressive changes are very well registered. Important warning signals are summarized in overview 4 .

Obesity and eating disorders

Obesity represents the largest group of eating disorders. Particularly in childhood and adolescence, the number of people affected is increasing sharply. About 15% of children and adolescents aged 3-17 years are overweight, and 6.3% are obese [4]. Obesity develops as a result of a diet too rich in calories combined with lack of exercise. The theoretical knowledge of this connection is often present in the young people, yet it seems almost impossible to change the triggering factors. In many cases, obesity is also based on psychological problems. Patients are often unstable in their psychosocial structures. Especially in the classroom they are often shunned or excluded. At the same time, the health problems that can arise from severe obesity are serious (e.g., diabetes, heart attacks, joint problems, hormone imbalances).

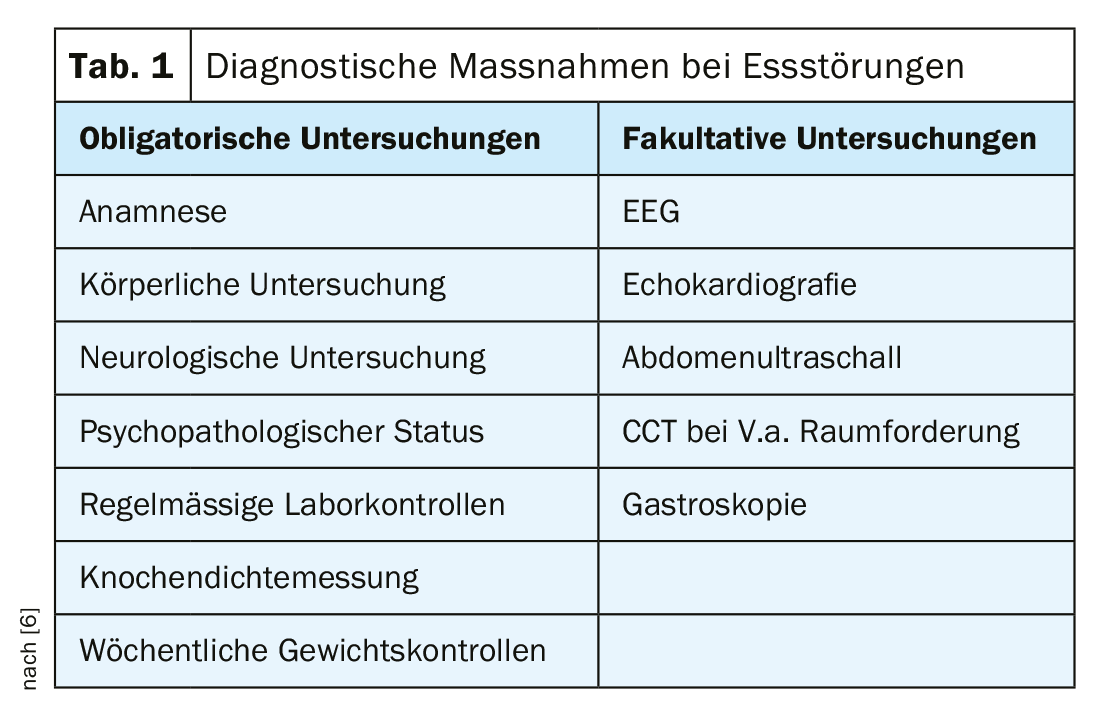

Diagnosis and differential diagnosis

The diagnosis of an eating disorder is made clinically on the basis of a systematic survey of the symptoms present (classification e.g. according to ICD-10). It is very problematic to overlook symptoms, as these are not reported even in severely ill patients despite inquiries. The cause here is often a denial of the symptoms by those affected. Also, the eating disorder symptoms present to the examiner are not accessible to the patient’s own perception. It is particularly problematic when those affected are reinforced in their illness by professionals not noticing the warning signs, as the following example shows:

A 16-year-old female patient is assigned weighing 35 kg with a height of 155 cm. She was very active in skiing until a year ago before the assignment, but since she was too light for great success, the patient switched to running on the recommendation of the sports physician. There, major performance problems arose, which the patient countered with an even more intensive diet.

This example shows that only sufficient diagnostic experience enables the physician to make the correct diagnosis. In this way, it is possible to reach an agreement with the person concerned on therapy, albeit sometimes only a limited one.

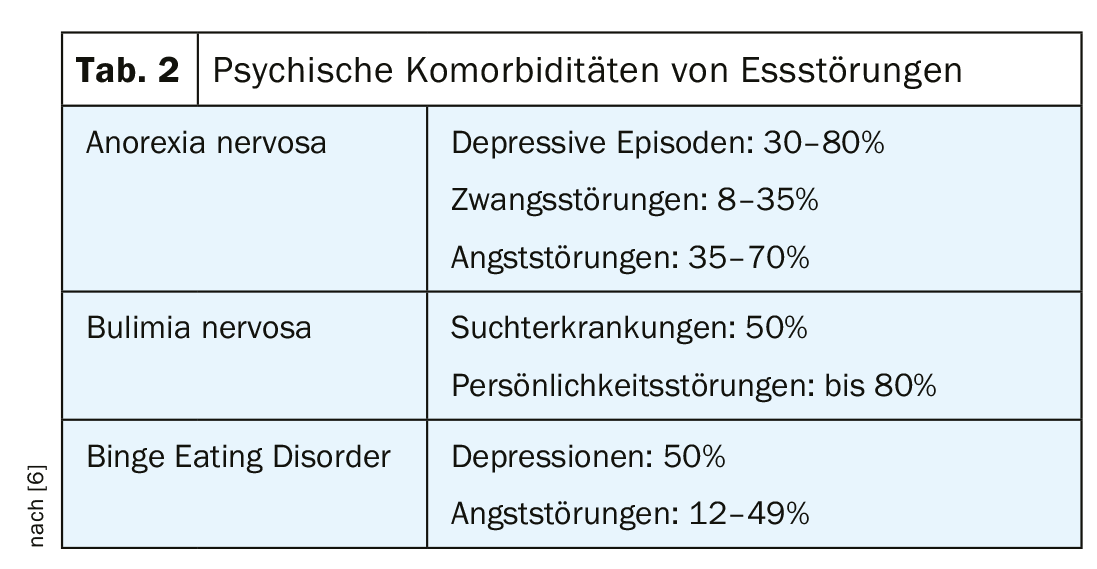

In the differential diagnosis, all diseases associated with weight loss, vomiting and lack of weight and size gain are relevant. However, it is crucial for the diagnosis of the eating disorder that the fear of gaining weight is behind the pathological behavior. There is an extreme determination of self-esteem by figure and weight. Depressive disorders, obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders, personality development and self-esteem disorders, and addictive disorders should be closely reviewed both as comorbidities and differential diagnoses (tables 1 and 2).

How dangerous are eating disorders?

All eating disorders can cause serious somatic and psychological disorders. Abdominal pain, slowed gastric emptying, and gastrointestinal constipation are common; this in turn can decrease food intake due to the feeling of fullness. Symptoms of the general economy mode of the body such as hair loss, lanugo hair on the body, increased freezing, cyanotic acra, dry skin and tugor loss of the skin, peripheral edema (esp. with weight gain), arterial hypotension, bradycardia, cardiac arrhythmias, pericardial effusions, petechiae due to thrombocytopenia, and yellowing of the skin due to hypercarotenemia. The triad of estrogen deficiency, hypocalcemia, and cortisol elevation often leads to osteoporosis. If the anorexia is not cured before completion of the epiphyseal joints, length growth is irreversibly impaired. In patients with BN, scars can often be found on the backs of the hands (“russel signs”). This is callus formation due to regular use of fingers to induce vomiting. Hypertrophy of the salivary glands and electrolyte imbalances (especially hypokalemia) are not uncommon. Also common are enamel defects, caries and ulcers of the oral mucosa. Massive ingestion of food can lead to perforation of the stomach wall with subsequent peritonitis. Abuse of diuretics is not infrequently associated with renal problems.

Regular laboratory checks often reveal pathological changes in electrolytes such as potassium and/or sodium deficiency with the risk of cerebral seizures or hypophosphatemia and elevation of bicarbonate in the sense of alkalosis. Leukopenia, low hemoglobin, and iron, zinc, or magnesium deficiency are very common. Low FT3 as a sign of reduction of thyroid hormones puts the organism in the saving mode. Reduction of liver function leads to increase of cholestasis parameters (AP and gamma GT) and reduction of liver synthesis parameters (CHE decreased). Cholesterol is very often elevated. A particular danger is the combination of hypoglycemia and physical exertion.

Eating disorder causes

There is no single explanatory model for the development of an eating disorder. It is assumed that there are several factors that lead to an eating disorder (multifactorial model). Three crucial classes of causes may play a role. We speak of predisposing, triggering and maintaining factors.

The predisposing factors can be divided into four subgroups:

- Biological (gender affiliation)

- Socio-cultural (ethnicity)

- Family

- Individual (psychologically stressful factors, self-esteem)

Triggering factors include the set of circumstances that trigger the initial onset of an eating disorder and determine the timing of the disorder. These include critical life events such as separation and loss experiences, new demands, fear of performance failure, physical illnesses, but also dieting and athletic ambition. Those affected are unable to adequately adapt to these new situations.

Sustaining factors include restrained eating behaviors, deficient coping with stress, and limited diversity of thought [5]. The maintaining ones are often linked to the predisposing factors. An eating disorder also leads to multiple biological and psychological changes that can contribute to the maintenance of the disorder – even when other factors originally involved in its development are no longer present [1].

Puberty as a phase of insecurity favors the development of eating disorders. School stress, thoughts about the future, career choices and sexual partners are new big challenges. Eating disorders can be a sign that the adolescent is not coping with himself or the situation. The illness thus becomes an “unconscious” expression of a serious crisis. The new media play a very special role in this. One’s self-esteem can be negatively affected by the rapid proliferation of seemingly normal appearance desired by society in unstable personalities.

Gender aspects

With regard to anorexia and binge eating disorder, the percentage of women suffering from the disease is many times higher than that of men (80-90% women). In recent years, however, it has become apparent that an increasing number of men are also becoming ill. The reasons for this gender mismatch are not clearly attributable. It is conceivable that girls are more likely to be overwhelmed by the earlier onset of their puberty-related body changes compared with earlier years. In boys, puberty sets in much later.

The demands on the role of women also pose a potential risk for the development of eating disorders. The role of women is no longer as clearly defined as it was a few decades ago. Job, family, beauty ideal – the modern woman is supposed to reconcile all of these. In their search for their place in society, women are very receptive to role models who seem to have successfully managed this balancing act. Physical beauty, especially slimness, counts in the media as proof of the successful outcome of this role conflict.

In men, it is often not being slim that is at the forefront of the disorder, but the feeling of not being worth the food because not enough has been accomplished (Adonis complex).

Therapy

Since eating disorder treatment is multimodal and multidisciplinary, it is necessary to determine who will be the case manager among all parties involved at the beginning of therapy. This also includes determining when and where, if necessary, outpatient therapy will be provided on an inpatient basis. Regular exchange among all treatment groups is essential to create an overall treatment plan and review it regularly. This exchange is particularly important at the transitions between different settings (outpatient, day hospital, clinic), as otherwise therapy may be discontinued.

In the treatment of eating disorders, a distinction must be made between medical and psychotherapeutic measures. In general, in addition to pediatric or general medical diagnosis and regular monitoring, psychotherapy is essential in all cases. Psychotherapy without competent medical supervision constitutes malpractice. An overall treatment plan is quite important, especially in anorexia. The normalization of body weight through the introduction of an eating plan is of particular importance here, in order to supply the brain, which is functionally impaired by malnutrition, with sufficient nutrients again.

Drug therapy is useful in anorexia only in the presence of comorbid conditions (severe compulsions or anxiety). However, there is currently good experience in some centers with low-dose antipsychotics (e.g., Abilify®). In bulimia nervosa, the use of SSRIs (e.g., fluoxitine) can provide symptom relief. Antidepressants and topiramate have been shown to be helpful in treating binge eating syndrome.

Psychotherapeutic treatment of eating disorders depends on the age of the patient and the type of eating disorder. For adolescent anorexia, systemic, family-based therapy has proven effective. There is no internationally accepted treatment recommendation for adult anorexia. For bulimia nervosa, cognitive behavioral therapy has been shown to be effective in all age groups, as it has been for binge-eating syndrome.

New treatment programs have been established in recent years, such as the online relapse prevention method or congnitive re-mediation therapy (CRT) for severe courses of anorexia. In all eating disorders, the support of parents and partners of those affected is indispensable.

Take-Home Messages

- Eating disorders are mostly multifactorial mental disorders. Intrapsychic, psychosocial, sociocultural, and biological factors influence or reinforce each other.

- Treatment is provided on an outpatient basis using cognitive-behavioral therapy or depth psychology. In the inpatient setting, multimodal treatments are provided. In the process, the inclusion of families has become more prevalent.

- Psychopharmacological measures are used to improve impulse breakthroughs for excessive eating in bulimia nervosa; in anorexia, they are used for severe anxiety or compulsions.

- Eating disorder therapy includes both psychological and somatic treatment. Psychotherapeutic treatment alone constitutes malpractice. To avoid dropouts, case management must be established early on.

Literature:

- Herpertz S, de Zwaan M, Zipfel S, eds: Handbook of Eating Disorders and Obesity. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 2015.

- Fairburn CG: Evidence-based treatment of anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord 2005; 37(Suppl): 26-30.

- Karwautz A: DGVM consensus process 12.12.2010. ÖAZ 2010; 19: 22-30.

- AKJ Switzerland: www.akj-ch.ch.

- Legenbauer T, Vocks S: Manual of cognitive behavioral therapy for anorexia and bulimia. Berlin/Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

- Treasure J, Alexander J: Beating anorexia together: a guide for sufferers, friends, and loved ones. Weinheim: Beltz, 2014.

- Tchanturia K, ed: Cognitive Remediation Therapy (CRT) for Eating and Weight Disorders. London: Routledge, 2014.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(3): 14-20.