Esophageal cancer occurs on average at age 60. It is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death. Robotic surgery allows more radical procedures under optimal visibility – for a better prognosis.

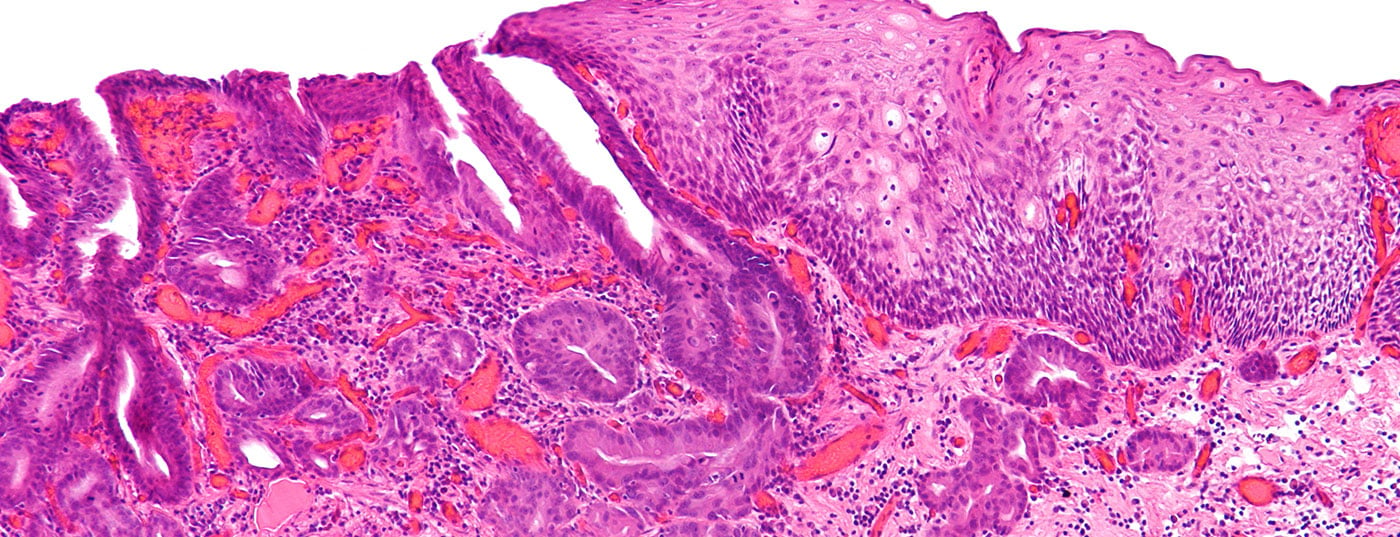

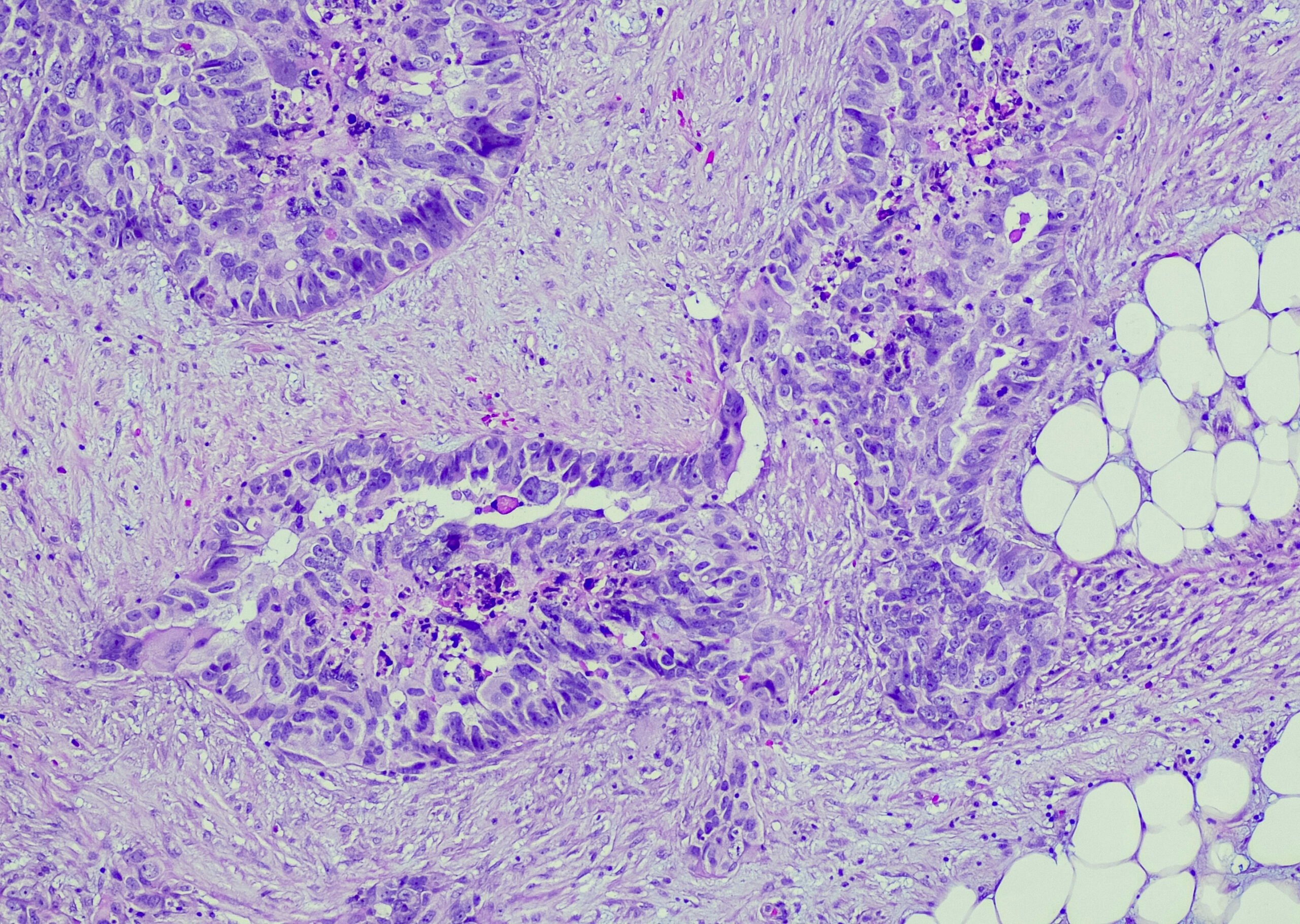

Esophageal cancer occurs on average at age 60. Three quarters of those affected are men, one quarter women. It is the sixth leading cause of cancer-related death [1]. Squamous cell carcinoma is found in the upper and middle thirds of the esophagus. Alcohol and nicotine use are prominent risk factors, and the incidence is stable. Adenocarcinoma arises in the lower third of the esophagus and at the junction with the stomach. Important risk factors are gastroesophageal reflux and obesity. The incidence of adenocarcinoma is strongly increasing and is more common than squamous cell carcinoma in Western countries. Other histologic forms play a minor role.

Staging

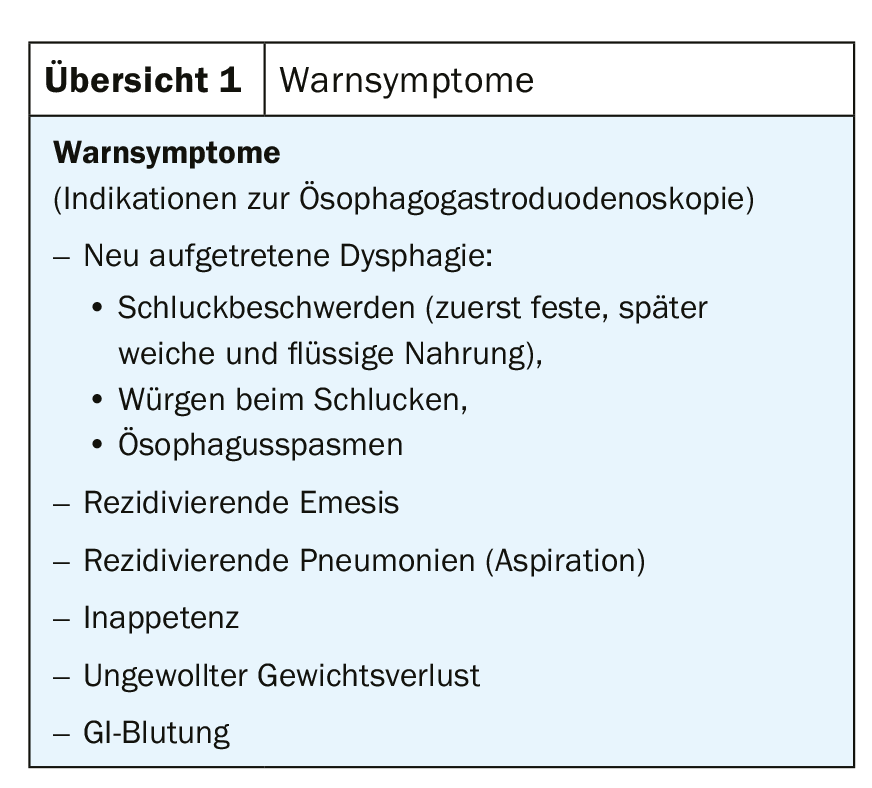

Esophageal carcinoma metastasizes early lymphatic and vascular. The 5-year survival rate is only 15-25% despite multimodal therapy [1]. The earliest possible diagnosis is therefore essential. As the primary care provider, the family physician is responsible for a rapid workup using esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGG) when warning symptoms are present (Overview 1) . Diagnostically, esophagogastroduodenoscopy has the highest sensitivity and specificity for neoplasms of the upper gastrointestinal tract.

Tumor centers with appropriate expertise are responsible for staging patients with esophageal cancer. Staging includes endosonography for the T- and N- categories and CT with PET to detect distant metastases (M-category) and as an index examination in the neoadjuvant approach. Bronchoscopy is performed for tumors with suspected invasion at the level of the carina or proximally. In squamous cell carcinoma, it is mandatory to exclude a synchronous ENT tumor. Laparoscopy is used to exclude peritoneal carcinomatosis or liver metastases (cT3-4) [2,3].

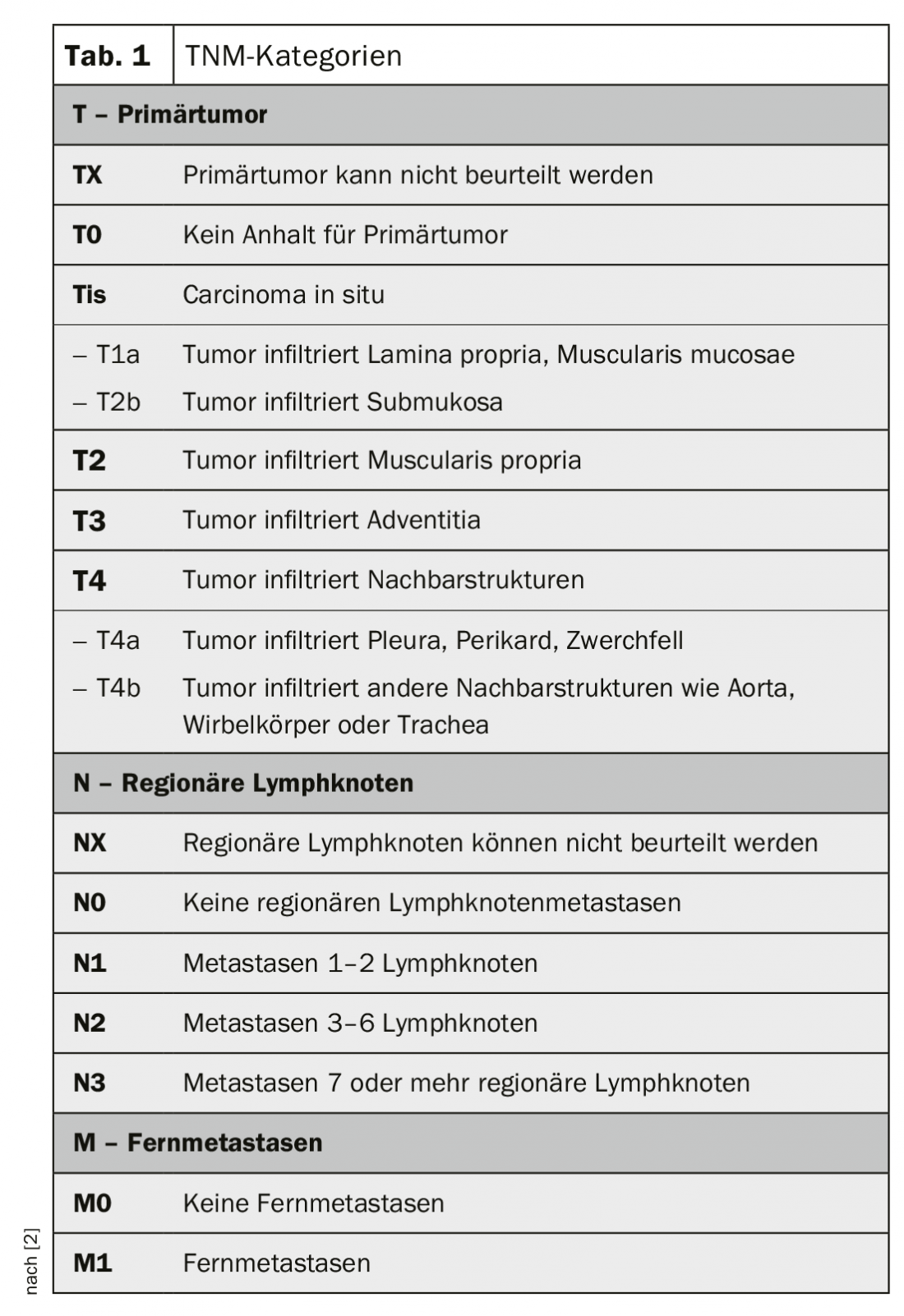

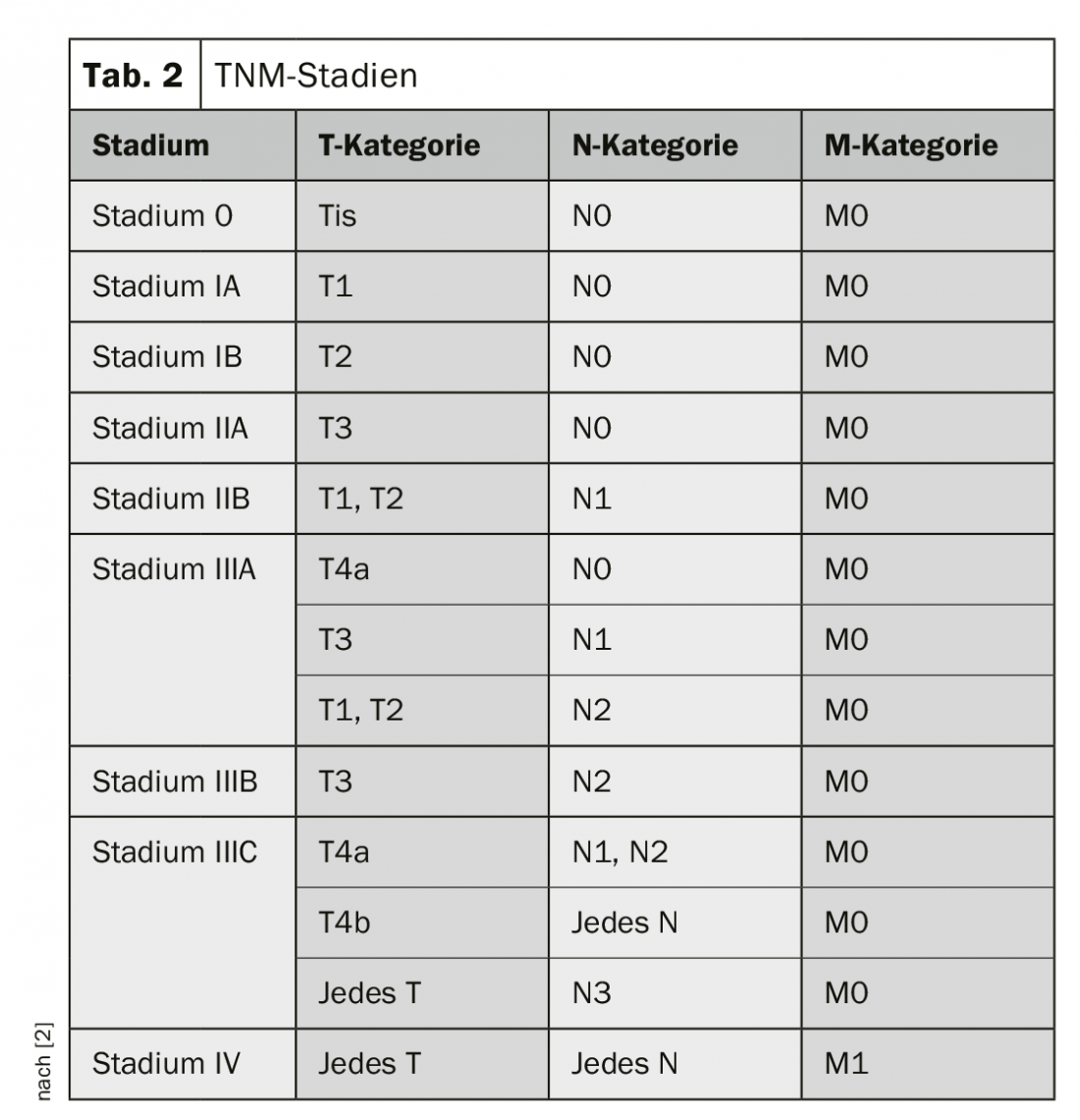

Classification of esophageal cancer

Classification and staging of esophageal cancer is according to the TNM classification (Table 1 and 2) [4]. Carcinomas of the esophagogastric junction, as long as their epicenter is no more than 2 cm distal to the Z-line, are considered esophageal carcinomas (Nishi classification [5]). Siewert classification [6] may continue to be crucial for surgical therapy. Similarly, Siewert type I and II are treated like esophageal carcinomas and type III like gastric carcinomas.

Therapy

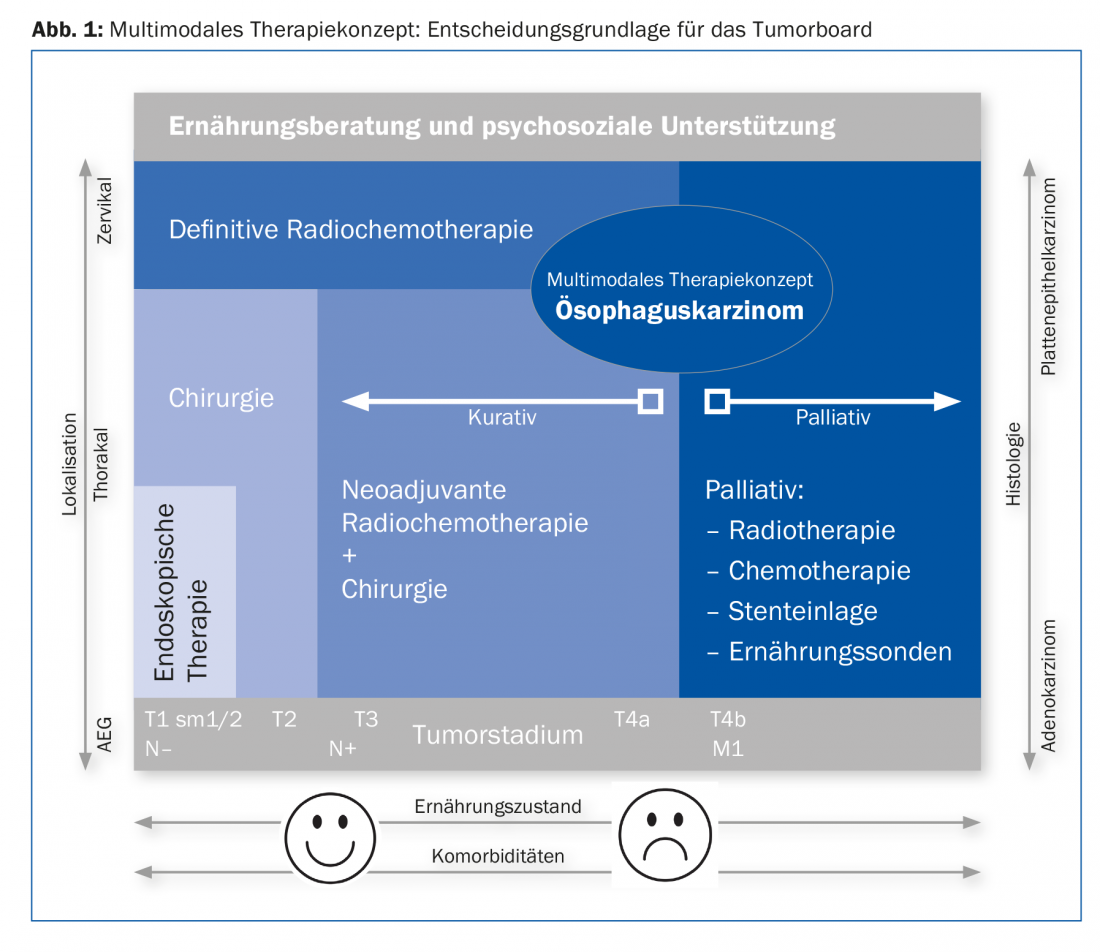

Therapeutically, the use of the robot plays a pioneering role. The treatment concept is determined at the tumor board after staging has been completed. The multimodal approach is outlined in Figure 1. A basic distinction is made between a curative and a palliative approach [2,3].

Curation

If locally there is at most a tumor stage T4a without distant metastases, we treat according to the curative concept. Early carcinomas (T1, sm1/sm2) without risk factors (L0, V0, maximum G2) can be treated endoscopically. For more advanced carcinomas, surgery is the treatment of choice after cardiac, pulmonary, hepatic, and metabolic risk assessment. We operate on T2 to T3 carcinomas or a positive nodal stage after neoadjuvant treatment. Several larger studies have demonstrated a survival benefit with pretreatment radiochemotherapy [7,8]. After neoadjuvant treatment, restaging is performed to exclude distant metastases. If distant metastases occur during or after therapy, it is discontinued and switched to a palliative approach. The optimal window for surgical intervention is six to eight weeks after completion of radiochemotherapy.

In non-resectable and cervical esophageal cancer, radiochemotherapy is the treatment of choice. Surgery here has a high complication rate with a consistent prognosis.

Nutritional status has a major impact on the postoperative course. Preoperatively, nutritional counseling with sip feeds (“immunonutrition”) [9] and, if necessary, with feeding tubes optimizes the conditions.

Robotic surgery

Robot-assisted hybrid technique is used to perform subtotal transthoracic esophagectomy with resection of the proximal stomach and reconstruction with gastric elevation and high intrathoracic anastomosis (Lewis surgery) for carcinomas of the middle and distal third [10]. This two-cavity procedure shows less reflux postoperatively due to the high intrathoracic anastomosis and allows a greater safety margin compared to transhiatal procedures. In addition, a clean two-field lymphadenectomy (thoracic and abdominal) can be performed. Survival increases with this approach [11].

For esophagectomy with the Da Vinci Xi® surgical robot, the abdominal portion is operated on via laparotomy for proximal gastric resection with lymphadenectomy, and the gastric tube is formed from the residual stomach. The thoracic part is performed entirely with the surgical robot. Four 8-mm trocars for the robot and a minithoracotomy at 5 cm are created to remove the resectate (Fig. 2) . A painful thoracotomy associated with increased morbidity postoperatively is thus avoided. The robot provides optimal three-dimensional vision with up to tenfold magnification and excellent freedom of movement. This allows clean lymphadenectomy as well as robot-assisted manual suturing of the intrathoracic anastomosis [12]. A prospective randomized trial showed fewer pulmonary complications, shorter hospitalization time, and better quality of life in favor of minimally invasive esophageal surgery over open surgery [13]. We performed the first robot-assisted esophagectomy in Europe with the Da Vinci Xi®, now oversee 30 robot-assisted esophagectomies and are convinced of this technique. We never had to convert, all resections were performed in healthy (R0) and morbidity was lower than in open surgery. No patient underwent reoperation within the first 30 days or died during that time.

Palliation

Chemotherapy is discussed with patients in a palliative situation. This has two goals: Preservation of quality of life and prolongation of survival. Chemotherapy should be started as early as possible. In choosing a therapeutic regimen, oncology is guided by the patient’s general condition, wishes, age and comorbidities, and toxicity. Additive antibody therapy is given when HER2 is positive in adenocarcinoma. Insertion of a stent may allow improvement of swallowing problems.

Aftercare

A follow-up regimen for treated esophageal cancer is rightly regularly requested, analogous to the consensus recommendations for follow-up after curatively operated colorectal carcinoma [14]. Such recommendations do not exist. Limited treatment options in recurrence and an often palliative situation make a standardized schematized approach impossible. There have been isolated attempts in clinical research to develop a structured follow-up [15]. This makes the consistent discussion of each patient at the interdisciplinary tumor board all the more important. This provides the primary care physician with an individualized recommendation for follow-up care. Follow-up is symptom-based and focuses on nutritional status and psychosocial support. Dysfunction may indicate recurrence. The nutritional counseling already initiated perioperatively is continued to ensure sufficient caloric intake and drinking quantity. If necessary, endoscopic or computed tomographic follow-up after six to twelve months is recommended on an individual basis at the tumor board. Primarily endoscopically resected patients undergo endoscopic follow-up.

Take-Home Messages

- Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is increasing.

- The family physician can decisively improve the poor prognosis through early detection (warning symptoms).

- Interdisciplinarity and center competencies are required.

- Robotic surgery allows more radical surgery under optimal visibility.

Literature:

- Pennathur A, et al: Esophageal carcinoma. Lancet 2013; 381: 400-412.

- Porschen R, et al: S3 guideline diagnosis and therapy of squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. Z Gastroenterol 2015; 53: 1288-1347.

- Lordick F, et al: Esophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol 2016; 27(S5): v50-v57.

- Brierley JD, et al: TNM Classification of malignant Tumours. 8th ed. UICC – Global Cancer Control. Oxford, UK, Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 2016.

- Japan Esophageal Society: Japanese Classification of Esophageal Cancer. 11th ed, parts II and III. esophagus 2017; 14: 37-65.

- Siewert JR, et al: Cardia Cancer: attempt at a therapeutically relevant classification. Surgeon 1987; 58: 25-32.

- Al-Batran SE, et al: Histopathological regression after neoadjuvant docetaxel, oxaliplatin, fluorouracil, and leucovorin versus epirubicin, cisplatin, and fluorouracil or capecitabine in patients with resectable gastric or gastrooesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (FLOT4-AIO): results from the phase 2 part of a multicentre, open-label, randomised phase 2/3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2016; 17: 1697-1708.

- Shapiro J, et al: Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol 2015; 16: 1090-1098.

- Mudge L, et al: Immunonutrition in patients undergoing esophageal cancer resection. Dis Esophagus 2011 Apr; 24(3): 160-165.

- Lewis I: The surgical treatment of carcinoma of the oesophagus; with special reference to a new operation for growths of the middle third. Br J Surg 1946 Jul; 34: 18-31.

- Peyre CG, et al: The number of lymph nodes removed predicts survival in esophageal cancer: an international study on the impact of extent of surgical resection. Ann Surg 2008; 248: 549-556.

- Cerfolio RJ, et al: Technical aspects and early results of robotic esophagectomy with chest anastomosis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2013 Jan; 145(1): 90-96.

- Biere SS, et al: Minimally invasive versus open oesophagectomy for patients with oesophageal cancer: a multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 1887-1892.

- Dorta G, Mottet C: Follow-up after colonoscopic polypectomy and removed colorectal cancer. SMF 2016; 16(7): 164-167.

- Baiocchi GL, et al: Follow-up after gastrectomy for cancer. The Charter Scaligero Consensus Conference. Gastric Cancer 2016; 19: 15-20.

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(9): 29-33

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2019; 7(6): 11-14.