A basic cure for the predisposition to atopic dermatitis is not possible. The genetic disposition is lifelong. Contrary to common belief, relevant trigger factors such as food or other allergies or other triggers continue to exist in only a relatively small proportion of children. The prognosis of atopic dermatitis is nevertheless good, and in three-quarters of cases the symptoms resolve by the age of ten.

Atopic dermatitis (synonym: atopic eczema, “neurodermatitis”, endogenous eczema) is an inflammatory, chronic or chronically recurrent skin disease associated with itching, which occurs frequently in families with other atopic diseases (bronchial asthma and/or allergic rhinoconjunctivitis). It arises on the ground of genetically determined dysfunction of the epidermal barrier and is not primarily an allergic reaction. Atopic dermatitis is one of the most common diseases in childhood. Up to 20% of all children and about 1-3% of adults are affected [1]. Mutations of important structural proteins of the skin (such as filaggrin) are crucial for the severity of atopic dermatitis and are also associated with increased atopic susceptibility (allergic asthma, peanut allergy) and increased susceptibility to infection (herpes infection). Approximately 10% of all individuals of European ancestry are heterozygous gene carriers for a loss-of-function mutation in the filaggrin gene. The prevalence of filaggrin gene mutations in patients with atopic dermatitis ranges from 20% to 50%. More common are altered copy numbers of filaggrin-encoding gene segments, and decreased expression of filaggrin is detectable in almost all moderate to severe cases of atopic dermatitis [2, 3]. The reduction of filaggrin in the skin leads to a skin barrier defect with increased water loss through the skin and increased transcutaneous allergen penetration. The result is dry skin and a tendency to typical eczematous inflammatory reactions.

Other trigger factors (Table 1) may worsen eczema but are not the cause of atopic eczema. Avoidance of these triggers leads at best to improvement, but almost never to healing of the eczema. Parents nevertheless often tie their diagnostic and therapeutic expectations to the fact that a factor can be found and eliminated, resulting in a cure for the disease. This often leads to very restrictive diets, sometimes dangerous to health, or refusal of vaccinations.

Vaccinations

The incidence of atopic dermatitis is the same in vaccinated and nonvaccinated children. Unjustified non-vaccination of eczema children leads to additional risk. Children with severe atopic eczema should even receive an extended vaccination schedule with varicella vaccination from 12 months of age (increased risk of bacterial skin and soft tissue infections and tendency to scarring due to impaired barrier) (Recommendation Swiss vaccination schedule 2012, BAG: Varicella vaccination of non-immune children with severe atopic eczema from 12 months of age).

Clinical presentation

Especially in the first months of life, it is often not possible to differentiate between seborrheic eczema and atopic eczema when eczema is present. Often, the characteristic symptoms of atopic dermatitis (especially itching) do not appear until the third month of life. In infants, the head and facial skin are predominantly affected (Fig. 1). There is often weeping, sometimes bacterially superinfected cheek eczema. The trunk of the body and the extensor sides of the extremities may also be affected. As the disease progresses, the large flexures are preferentially affected (Fig. 2), although in principle other sites on the trunk, extremities and head may also show eczema.

In adolescence and young adulthood, persistence or recurrence of atopic dermatitis increasingly affects the neck and face and the hand-foot area. A variant of atopic dermatitis that occurs in approximately 10-15% of children is nummular atopic eczema (Fig. 3). Nummular lesions are often more resistant to therapy than typical patchy eczema.

Early colonization with Staphylococcus aureus occurs on the barrier-damaged skin (90-100% of all children with atopic dermatitis – compared to 20-25% in healthy children). Staphylococcal toxins directly lead to worsening of eczema. In addition, particularly in the head region and especially in very young children, weeping impetiginized eczema and pyoderma may develop.

Diagnostics

An allergological diagnosis is not fundamentally necessary, especially in childhood. Especially in exclusively breastfed infants, it usually has no consequence. If the eczema recedes well under optimized basic and temporary specific therapy, further laboratory diagnostics can also be dispensed with.

However, laboratory and allergological diagnostics are in principle useful in case of indications for an allergic immediate-type reaction (such as edema, urticaria or vomiting after food intake/allergen contact) and in case of moderate and severe eczema with a long-term high need for anti-inflammatory therapy (total IgE, house dust mites, depending on age food and environmental allergens and possibly others according to history).

The determination of IgE against environmental allergens (sx1) is useful if anamnestically ascertainable factors such as pollen season, winter season (house dust mites) or pet contact lead to exacerbations of atopic dermatitis.

In addition, children with atopic dermatitis and associated atopic diathesis have an increased risk of developing allergies to inhalants (hay fever, allergic asthma) and/or partially associated food allergies (e.g., birch pollen-associated food allergies to raw stone and pome fruits or celery) at the same time or especially later. Children with elevated specific IgE to environmental allergens also require special counseling in later career choices. Certain professions such as baker, florist or animal caretaker are unsuitable for them because of the increased risk of allergic rhinitis or asthma.

Differential diagnoses

Differential diagnoses of atopic dermatitis in childhood include seborrheic eczema (especially in infants), scabies, contact dermatitis, psoriasis, and Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Likewise, a possible zinc deficiency can lead to eczematous changes, especially in the periorificial area.

Therapy

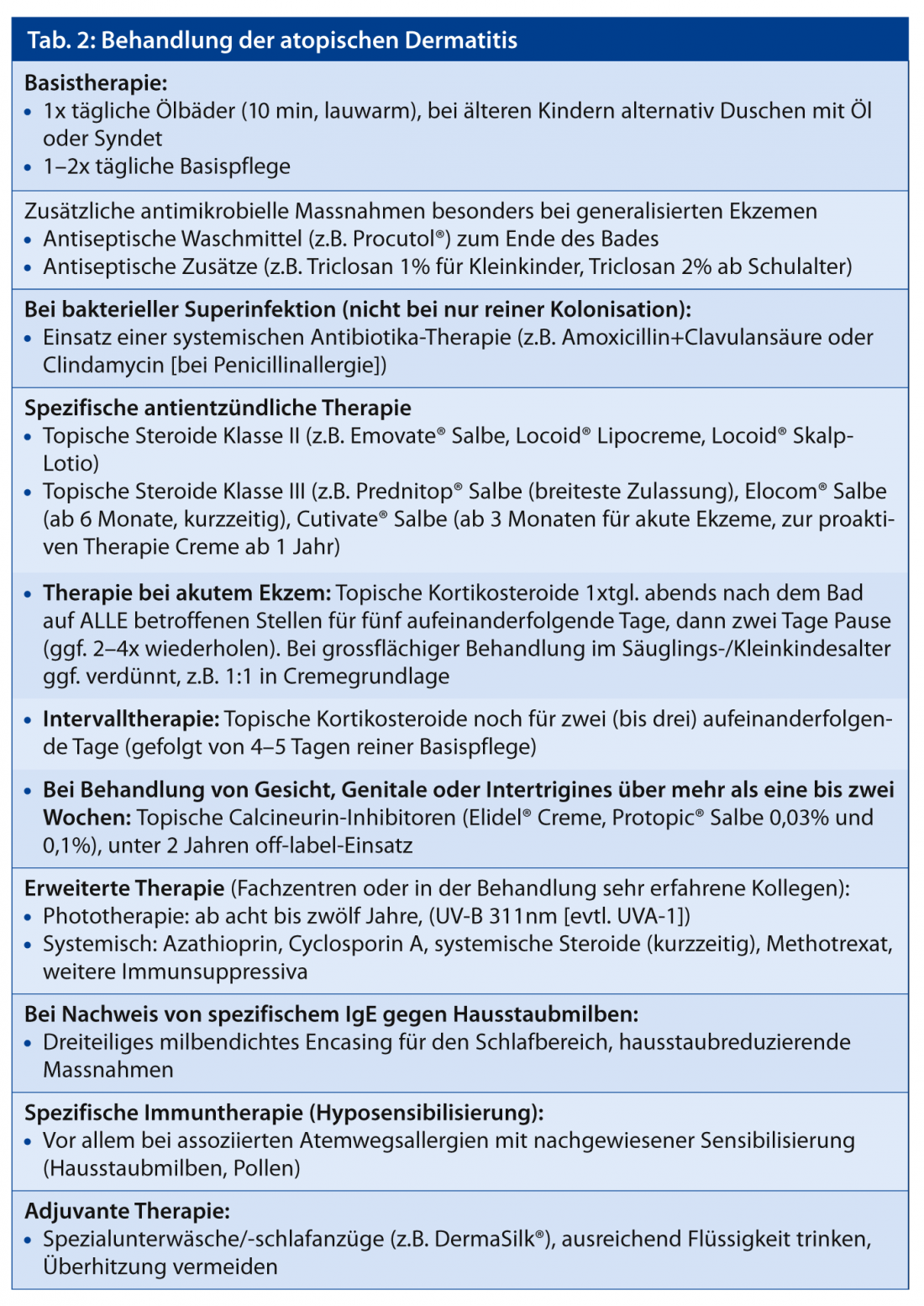

The goal of therapy (Tab. 2) is to achieve complete freedom from symptoms and sustained control of new eczema flare-ups. Only after the inflammation/eczema has healed can the epidermal barrier be kept optimally intact with the aid of basic therapy. With regard to a good prognosis with prevention of chronification of eczema, the guiding principle “no tolerance for eczema” is central, and proactive management is indicated. The therapy is based on the following principles [4]:

- Restoration of the epidermal barrier by means of adapted basic therapy (skin cleansing and lipid-replenishing care)

- Prophylaxis and treatment of cutaneous superinfection by means of adapted basic therapy including regular skin cleansing and anti-inflammatory local therapy (antiseptics, antibiotics if necessary, corticosteroids)

- Consistent anti-inflammatory therapy with the goal of promptly bringing eczema flare-ups to healing and preventing further flare-ups.

Basic therapy

The basic therapy consists of cleansing measures and moisturizing care products adapted to the stage, localization of eczema and age of the child.

The younger the children, the more important is regular cleansing and hydration of the skin by means of daily lukewarm baths with an oil additive. Older children may also be given oil showers or showers with moisturizing agents that are gentle on the skin (e.g., syndets). Bathing and showering removes ointment residues and counteracts unfavorable microbial colonization of the skin. During the first ten to 15 minutes after the bath, there is also improved absorption of topically applied substances into the epidermis [5].

If there is a tendency to bacterial superinfections, the bath or shower can be supplemented with an antiseptic skin-friendly wash lotion. Alternatively, antiseptics (e.g. triclosan 1-2%) can be mixed into the care products. Which product is used for basic therapy must be determined individually; the lipid content in particular can be adapted to the dryness of the skin. Externals should contain as few fragrances, preservatives or emulsifiers as possible. For an additional rehydrating effect, substances such as glycerin or urea can be added to base products. Urea can cause a temporary burning sensation (“stinging” effect) on the skin, especially in infants and young children, and is therefore ideally only used from preschool age.

Specific therapy

Topical corticosteroids have been used in the local therapy of atopic dermatitis for more than 50 years and there is a very wide range of experience and safety. Side effects of a correctly applied topical therapy are extremely rare and have nothing in common with the side effects of internal steroid preparations known to some patients/parents. Any skin atrophy, the formation of striae or steroid acne can almost always be avoided by the correct use of the preparations. Nevertheless, when prescribing these preparations, the “cortisone talk” with the parents is inevitable. Here, the following should be addressed:

- General differences of corticosteroids systemic/topical

- Different strength classes (class I weak to class IV strongest) of topical preparations (note: the percentage of steroid concentration is only important for differences in potency of the same substance, but says nothing about the strength class of different corticosteroids); advantages of the so-called “soft steroids” (non-fluorinated corticosteroids)

- Long-term safety aspects due to the already decades of experience

- Importance and safety of interval application

- Strategy of proactive therapy for better prognosis and prevention of eczema chronicity.

For the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis, topical steroids of classes II and III (classes I and II in young infants) are particularly recommended in children. Treatment once a day is sufficient here (depot formation of the topical steroids in the stratum corneum), ideally this should be carried out in the evening after bathing.

For acute episodes of atopic dermatitis, intensive therapy is recommended by means of treatment for five consecutive days – followed by a two-day break. Depending on the severity of eczema, these cycles must be repeated several times (for example, 2-4×). If the skin improves, a reduction to interval therapy can then be made. Here, topical steroids are applied to the primarily affected areas on two to three treatment days (consecutively) per week.

Except for very mild eczema that heals completely within a few days, topical corticosteroids should not be discontinued abruptly, but should be phased out slowly by reducing the duration of use to, for example, two days per week (interval therapy). This prevents unwanted rebound and recurrence of eczema.

Note: When starting therapy, a sufficiently strong cortisone preparation should be chosen in order to achieve healing as quickly as possible. When tapering therapy, the same preparation should be used as interval therapy (but not switched to a weaker preparation).

In the case of frequent eczema flare-ups, such interval therapy can also be continued for a few months in the sense of proactive therapy when eczema is already well controlled. The goal of proactive treatment is to prevent new eczema flare-ups from occurring in the first place, thus achieving longer-term stabilization and healing of atopic dermatitis.

Calcineurin inhibitors inhibit T-cell activation and specifically interfere with the inflammatory process of atopic eczema. Pimecrolimus (Elidel® cream) and tacrolimus (Protopic® ointment) have been shown to be effective in children [6]. The potency of Elidel® cream corresponds approximately to a topical steroid class I, that of Protopic® ointment 0.1% to a class II steroid. Compared to topical corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors do not pose any risks with regard to skin atrophy, especially in long-term applications. They are therefore particularly suitable for problematic areas (face, intertriginous areas, anogenital).

Proactive therapy can also be performed with calcineurin inhibitors. The preparations are approved from the third year of life and, in principle, as second-line therapeutics. However, due to the increased risk of steroid side effects, these preparations are particularly well suited for successful long-term control and healing in infants and young children with persistent eyelid, cheek, and perioral eczema.

The main undesirable effect is a burning sensation that develops a few minutes after application of the preparations, but this occurs mainly in acute eczema and is observed much less frequently in children than in adults. For acute inflammatory findings, short-term pretreatment with a topical steroid is recommended. Storing calcineurin inhibitors in the refrigerator can also partially reduce burning.

Based on previous experience, the concern of a potentially increased oncogenic risk from long-term use of topical calcineurin inhibitors cannot be substantiated by specific cases [7]. However, in order to take into account a possible additional immunosuppressive effect in combination with UV light exposure, these preparations should preferably be used in the evening and accompanied by adequate sun protection measures.

Due to the immune reducing effect mainly on T cells, skin infections such as a herpes simplex infection or the presence of dell warts (Mollusca contagiosa) or HPV warts during the acute infection are a contraindication for the use of Protopic® or Elidel®.

Complementary measures

As a supportive measure, the basic therapy can be extended to include special textiles (e.g. Derma Silk®, an antimicrobial silk textile). These are mainly worn as pajamas or underwear and result in additional skin protection and reduction of microorganisms on the skin and thus improved skin condition and reduced itching.

Antihistamines can be used to treat the itching. Sedating antihistamines such as dimetindene (Feniallerg®) should only be used in infants and/or at night. In older children, non-sedating antihistamines such as desloratadine (Aerius®, approved from 6 months) or levocetirizine (Xyzal®, approved from 24 months) are recommended during the day. Relief of pruritus can be supported by additional measures such as the use of antipruritic additives (e.g., polidocanol 5%) in the topical base therapeutics.

Conclusion for practice

The cause of atopic dermatitis is a genetically determined skin barrier defect. Various trigger factors may additionally influence the severity and frequency of eczema flare-ups, but are not causative for the disease. Basic therapeutic measures serve primarily to permanently stabilize the skin barrier and to prophylactically prevent new eczema flare-ups. Here, the entire skin should be treated and this therapy should be continued especially in symptom-free periods. Inflammatory changes of the skin generally require an adapted anti-inflammatory therapy (topical corticosteroids and, if necessary, calcineurin inhibitors). There is now evidence that early proactive eczema therapy with restoration of the skin barrier counteracts the development of allergies.

Patients and their parents should be well acquainted with their disease as it progresses. In order to deal with the manifold questions also with regard to nutrition and skin treatment, interdisciplinary training courses for those affected (children and their parents) are ideal in addition to sufficient consultation time with a physician experienced in pediatric dermatology. Various centers offer such training cycles (e.g. www.aha.ch, Allergy Center Switzerland). In addition to professional training, participants here can also benefit from exchanging ideas with other people affected.

Literature list at the publisher

Marc Pleimes, MD

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2013; 23(1): 8-12