In recent years, the number of disease-modifying therapies for the treatment of multiple sclerosis has increased dramatically. Increasing data support the early use of highly effective therapies (HRT), which can significantly alter the course of the disease and delay progression.

5

As a chronic autoimmune disease, multiple sclerosis (MS) is characterized by inflammatory reactions in the central nervous system (CNS). MS affects approximately 2.8 million people worldwide (as of 2020)1 and it is the most common neurodegenerative disease of the CNS in young adults.2 Over time, lesions and neuro-axonal damage accumulate, irreversible clinical and cognitive deficits manifest, and disability progression occurs.

2

MS rarely follows a benign course

3

Data from a North American registry of 25,728 MS patients showed that a majority of patients already have some degree of various symptoms at disease onset.

3

Among these, 85% of patients were affected by sensory impairment and 81% by fatigue.

3

During the course of the disease, the symptoms usually worsened and the severity of impairment increased.3

The authors of a cohort study from Wales even found, based on a representative sample of 60 untreated patients, that benign MS was present in only 15% (9/60).4 This was defined as: EDSS score < 3, no significant fatigue, mood swings, or cognitive impairment, and no interrupted employment status. However, the proportion of patients who considered their MS to be benign was more than three times higher (69%).4 This clearly demonstrates that fewer disease courses than assumed follow a mild course.

The current ability to predict disease progression at baseline is very limited and difficult.5 Long-term follow-up studies demonstrated the risks of possible undertreatment and that the extent of brain damage caused by MS is often underestimated.

5

A potentially more sensitive and comprehensive assessment of inflammatory and neurodegenerative processes may be enabled by the use of a composite end point, for example, NEDA-3 (no evidence of disease activity).

6

To date, there are too few data to establish NEDA as a standard end point. However, preliminary evidence suggests that NEDA-3 status at two years may be a predictor of long-term absence of disease progression.7

Broad spectrum of therapy options

In recent years, the range of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) has continued to expand. Therapeutic options differ in approach to action, route of administration, frequency of use, and efficacy and safety. Based on the individual situation of the patient, a suitable therapy can be found. However, to date there is no consensus according to international guidelines for optimal use.

8-10

Especially in the past, the principle of escalation therapy (ESC) was frequently used. Patients with a benign disease course are started on a moderately effective therapy and only switched to a highly effective therapy (HET) when the symptoms of the disease can no longer be adequately controlled.5 In most cases, this was expected to protect patients from unexpected side effects in early phases of therapy.

5

However, ESC carries the risk that, despite many years of treatment, the disease may be insufficiently controlled in phases due to undertreatment, and therefore there may be worsening of clinical and imaging parameters and significant disease progression.5,11-13

Advantages of early initiation of highly effective therapy (HRT).

Findings in recent years highlight the advantages for early use of HRT: the course of the disease can be significantly altered and irreversible progression can be delayed.14,15 For such early intervention, a “window of therapeutic opportunity” seems to exist: During this time, the disease biology can be modified such that the long-term course is more favorable under HRT than under ESC.14

An analysis of 592 patients achieved better results over a five-year period in terms of annual relapse rate and EDSS score under HRT compared with ESC.14 Monoclonal antibodies were considered as HET – all other DMTs were assigned moderate efficacy. Also, the median time to sustained accumulation of disability (SAD) was twice as long in the group that received early HRT compared with the ESC group (6.0 years vs. 3.14 years; p = 0.05).14

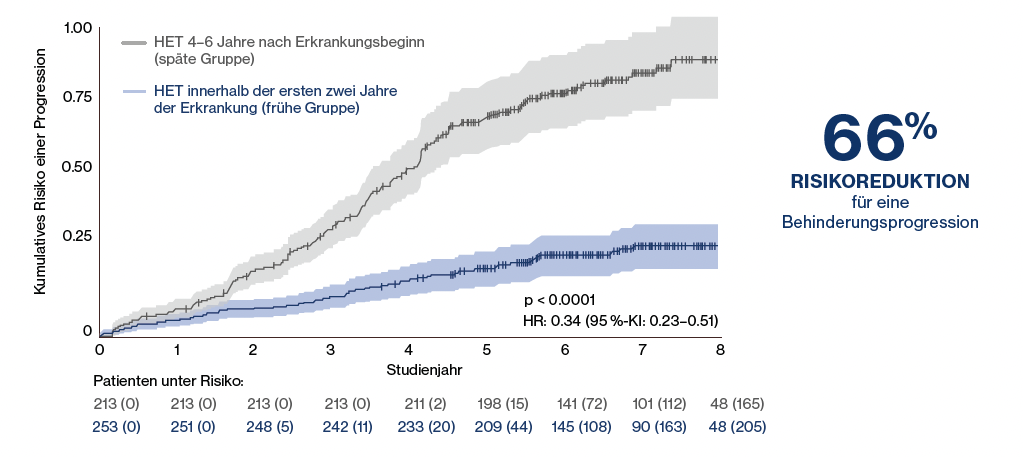

That the timing of the use of HRT is particularly critical was also shown by a retrospective analysis of 544 patients, in which early use within the first two years of disease was compared with later use four to six years after disease onset: The risk of confirmed disability progression was significantly reduced by 66% (p < 0.0001;

Figure 1

).

15

Figure 1:

Significant risk reduction for confirmed disability progression in patients who received high efficacy therapy (HRT) within the first 2 years of disease compared to patients in the late group who did not receive HRT until 4-6 years after disease onset (measured from the start of first course therapy). Adapted from He A, et al. 2020.15

A meta-analysis of 38 clinical trials involving more than 28,000 MS patients also demonstrated that HRT is beneficial for the average patient only in the early disease phase. In patients under 40.5 years of age with HRT, better results in terms of disability reduction were achieved than with less effective drugs.16 The positive impact on disease progression highlights the importance of new, highly effective drugs in first-line therapy.

Classification of HETs

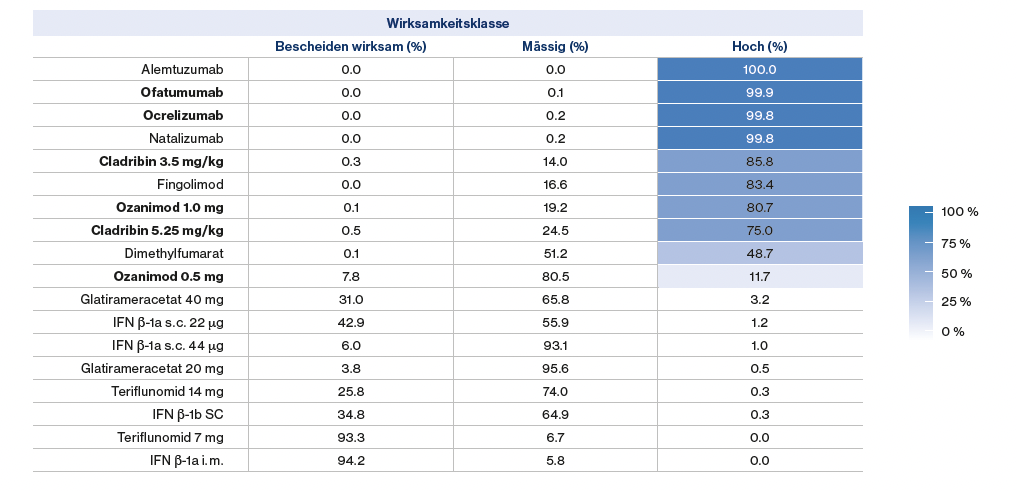

A recent network analysis derived the efficacy of the various DMTs by incorporating direct and indirect evidence.17 Using the annual thrust rate, probabilities for the efficacy classes of DMTs were derived in this way, and a classification was made into highly, moderately, and modestly effective (

Figure 2

). Alemtuzumab and ofatumumab were rated as the most highly effective therapies, with probabilities of 100% and 99.9%, respectively.

17

Figure 2:

Classification of disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) based on their efficacy class probability derived from annual relapse rate. Adapted from Samjoo IA, et al. 2021.17

Balance between efficacy and safety

In daily practice, a balance must be struck between efficacy and safety. Today, there are therapies that make this easy: Ofatumumab, for example, is a highly effective therapy that offers a favorable safety and tolerability profile comparable to teriflunomide.17 offers a favorable safety and tolerability profile comparable to teriflunomide.

18

Published long-term safety data over 3.5 years of ofatumumab confirm the safety profile.19 Especially younger MS patients with an active lifestyle, for whom family and work should be as little affected as possible by their disease, could benefit from a highly effective, well-tolerated and flexible therapy.5,11,16 Therapy with ofatumumab is easy to start and flexible to manage.20 After an initial dosing period, ofatumumab is administered by self-application once monthly at home without premedication.20 This flexibility is well suited to the lifestyles of young, active patients.

Key Messages

- Only rarely does multiple sclerosis follow a benign course.3,4

- However, prediction of disease progression at onset is very limited and difficult.5

- A wide range of disease-modifying therapies are available for MS treatment.

- More and more data support the early use of highly effective therapies that can positively influence disease progression and delay irreversible progression.

14-16

- Today, highly effective therapies such as ofatumumab combine efficacy and safety, and are also easy to start and flexible to manage.

17-20

References:

- Atlas of MS 3rd edition. https://www.atlasofms.org/map/global/epidemiology/number-of-people-with-ms, last accessed Dec. 13, 2021.

- Filippi M, et al. Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):43.

- Kister I, et al. Natural history of multiple sclerosis symptoms. Int J MS Care. 2013;15(3):146-158.

- Tallantyre EC, et al. How common is truly benign MS in a UK population? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2019;90(5):522-528.

- Stankiewicz JM, and Weiner HL,. An argument for broad use of high efficacy treatments in early multiple sclerosis. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2019;7(1):e636.

- Parks N et al. NEDA treatment target? No evident disease activity as an actionable outcome in practice. J Neurol Sci. 2017;383:31-34.

- Rotstein DL et al. Evaluation of no evidence of disease activity in a 7-year longitudinal multiple sclerosis cohort. JAMA Neurol 2015;72(2):152-8.

- Rae-Grant A, et al. Comprehensive systematic review summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2018;90:789-800.

- Montalban X, et al. ECTRIMS/EAN Guideline on the pharmacological treatment of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2018;24:96-120.

- Rae-Grant A, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: Disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis. Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-88.

- Giovannoni G, et al. Brain health: time matters in multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2016;9 Suppl 1:S5-S48.

- The Multiple Sclerosis Coalition. The use of disease-modifying therapies in multiple sc lerosis: principles and current evidence. http://ms-coalition.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/MSC_DMTPaper_062019.pdf. First published July 2014, updated June 2019, last accessed Dec. 13, 2021.

- Ford C, et al. Continuous long-term immunomodulatory therapy in relapsing multiple sclerosis: results from the 15-year analysis of the US prospective open-label study of glatiramer acetate. Mult Scler. 2010;16(3):342-50.

- Harding K, et al. Clinical outcomes of escalation vs early intensive disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis. JAMA Neurol. 2019;76(5):536-41.

- He A, et al. Timing of high-efficacy therapy for multiple sclerosis: a retrospective observational cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(4):307-16.

- Weideman AM, et al. Meta-analysis of the Age-Dependent Efficacy of Multiple Sclerosis Treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

- Samjoo IA, et al. Efficacy classification of modern therapies in multiple sclerosis. J Comp Eff Res. 2021;10(6):495-507.

- Hauser SL et al. Ofatumumab versus Teriflunomide in Multiple Sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):546-557.

- Hauser SL, et al. Safety experience with continued exposure to ofatumumab in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis for up to 3.5 years . Mult Scler. 2022; 13524585221079731. doi: 10.1177/13524585221079731.

- KESIMPTA® Technical Information, www.swissmedicinfo.ch; January 2021.

Novartis will provide the listed references upon request.

KESIMPTA

®

Solution for injection in a ready-to-use pen ▼.

This medicinal product is subject to additional monitoring. For more information, see the Kesimpta SmPC at www.swissmedicinfo.ch.

Z:

1 prefilled pen contains 20 mg of ofatumumab in 0.4 ml solution for subcutaneous injection (50 mg/ml). I: Kesimpta is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with active relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis (MS).

D:

20 mg as a subcutaneous injection: initial administration at weeks 0, 1, and 2, followed by subsequent monthly administrations beginning at week 4.

AI:

Hypersensitivity to the active ingredient or any of the excipients listed in the composition section, severely immunocompromised patients, presence of active infection, known active malignancies, initiation of therapy during pregnancy.

VM:

Warnings and precautions regarding injection-related reactions, infections, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, hepatitis B virus reactivation, treatment of highly immunocompromised patients, treatment with immunosuppressants before, during, or after treatment with ofatumumab, vaccinations, malignancies. IA: B-cell depletion may reduce the immune response to vaccination. Possible additive immunosuppressive effects when switching from other immunosuppressive or immune-modulating therapies to Kesimpta should be considered. UW: Very common: Upper respiratory tract infection, urinary tract infection, headache, injection site reactions (local), injection-related reactions (systemic). Common: Oral herpes, decreased serum immunoglobulin M (IgM) levels. P: 1 ready-to-use 0.4 ml pen. Levy category: [B]. For more information, visit www.swissmedicinfo.ch. Status of information: January 2021 V01. Novartis Pharma Schweiz AG, Risch; address: Suurstoffi 14, 6343 Rotkreuz, Tel. 041 763 71 11

This article was realized by Novartis Pharma Schweiz AG, Suurstoffi 14, 6343 Rotkreuz,Switzerland

NO57236/05.2022