Things are happening again in the field of urticaria management. Classification as well as treatment recommendations have been updated and new insights have been gained in causal research, which may allow individual and targeted urticaria therapy in the future.

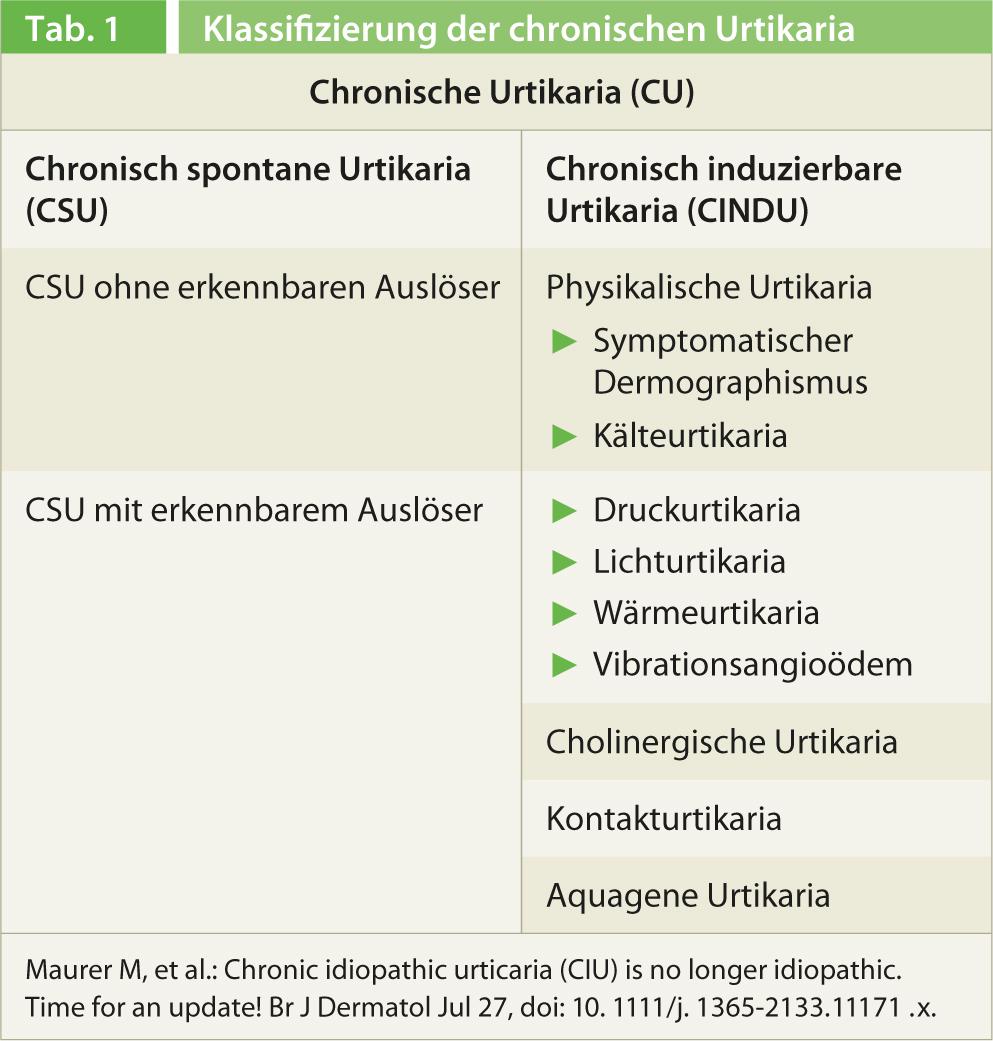

At this year’s annual meeting of the Swiss Allergy and Immunology (SGAI) and Pneumology (SGP) Societies in Bern, Prof. Clive Grattan, MD, St. John’s Institute of Dermatology, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, UK, gave an interesting update on urticaria management. He elaborated that the disease has received a new, simpler classification and a clearer treatment recommendation as part of the 2012 Berlin Urticaria Consensus Conference. Although the recommendations are based on the previous guidelines from 2009 [1] and a distinction is made between acute and chronic urticaria (duration </>6 weeks) depending on the duration of the disease, the latter is now only differentiated between spontaneous and inducible forms (Table 1). The term idiopathic urticaria no longer appears in the new classification. In chronic spontaneous urticaria, i.e., without a recognizable trigger, such as cold or physical exertion, a subgroup is distinguished with detectable triggers (e.g., a histamine-releasing autoantibody in the serum) and without them. If a specific cause can be identified, it should be stated in the diagnosis, i.e., chronic spontaneous urticaria with autoantibody detection.

Moving away from the term chronic idiopathic urticaria to the use of chronic spontaneous urticaria with an indication of the cause will lead to better clarification of the underlying condition and, accordingly, more effective treatment.

Rethinking the treatment of urticaria

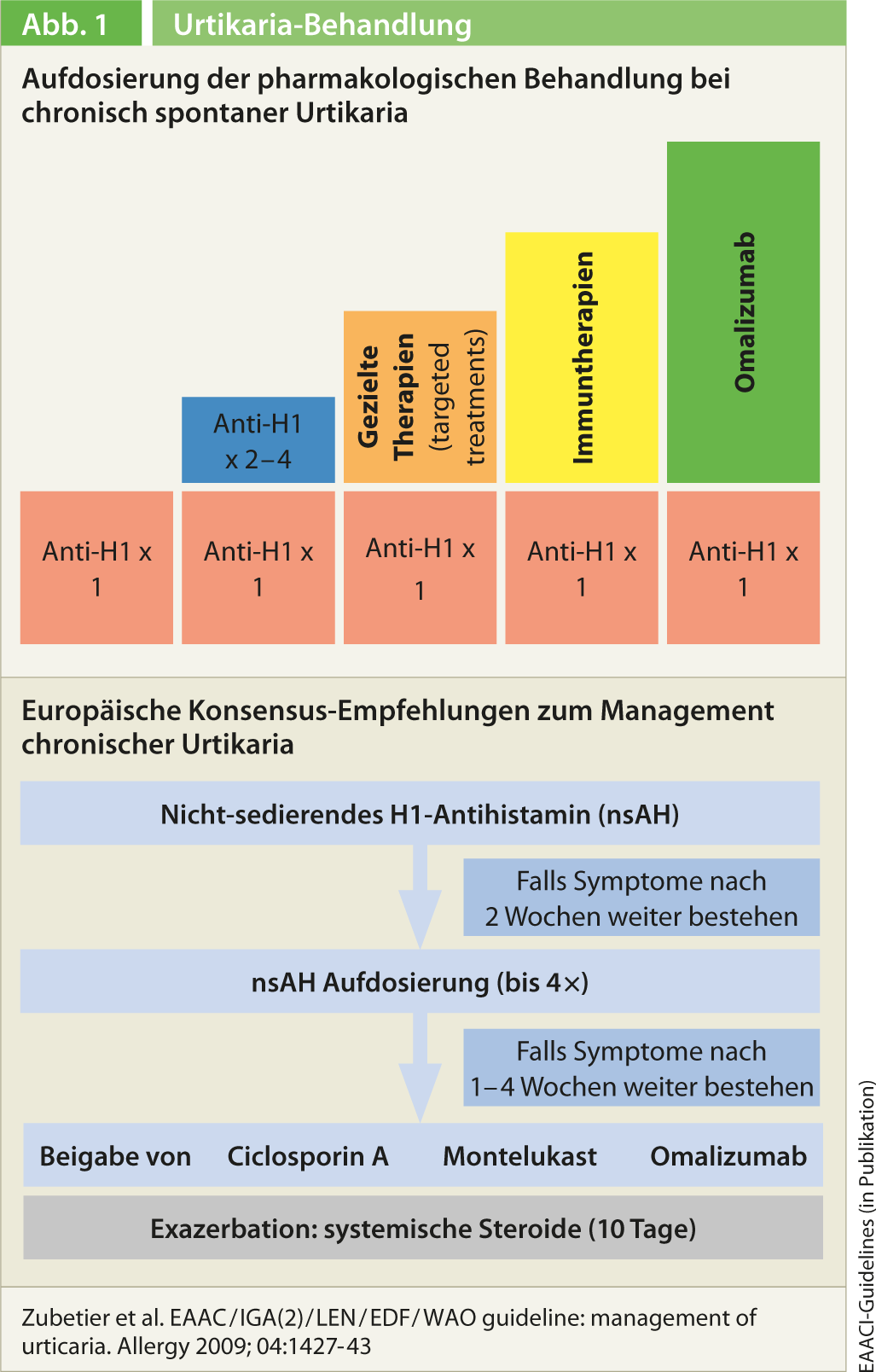

During the Berlin Urticaria Consensus Conference last fall, the 2009 treatment recommendations were also revised and simplified [2]. First-line treatment is as before with a second-generation non-sedating H1 antihistamine. If the standard dosage does not bring the desired success, the antihistamine should not be changed, but the dose should be increased up to a maximum of four times (Fig. 1). There is now sufficient data for this treatment strategy, as Prof. Grattan explained. In patients who do not respond to this either, combination with second-line treatment is indicated. Prof. Grattan first mentioned a combination with H2 antihistamines here. Corticosteroids are recommended only as a last resort and only as a maximum of two weeks of intermittent therapy. Prior to this, combination therapies with ciclosporin, leukotriene antagonists, and the anti-IgE antibody omalizumab should be tried (montelukast in particular is recommended as adjunctive therapy). These are off-label applications that require a cost approval by the health insurance company, as does, strictly speaking, high-dose therapy with H1 antihistamines. Regarding dapsone, it is not possible to make a recommendation. Overall, the same treatment algorithm is proposed in children, during pregnancy and lactation.

New therapy options

With regard to therapeutic options, Prof. Grattan discussed the two new therapeutic approaches with bilastine and omalizumab. The first-line H1 antihistamine bilastine shows, according to Prof.

Grattan, with good tolerability promising treatment results. He presented a study that investigated the effect of bilastine at doses of 20, 40, and 80*mg on cold urticaria compared with placebo [3]. The reduction of the critical threshold temperature at which wheals and erythema appeared was measured. Bilastine treatment (20, 40, and 80 mg) significantly reduced this temperature to below 4°C compared with placebo. Temperature reduction was weaker in the 20 mg bilastine group than under 80 mg, as well as at 40 mg compared with 80 mg, once again illustrating the benefit of up-dosing according to the new guidelines. Also of interest, Prof. Grattan said, was that mast cell mediators histamine, IL-6, and IL-8, but not TNF-α, were significantly lower under bilastin 80 mg one to three hours after cold induction. These data suggest that the stronger effect of bilastine at the higher dose may be due to an additional anti-inflammatory effect.

Prof. Grattan further elaborated on a study regarding sedation, a common side effect under H1 antihistamines. In rats, bilastine was shown not to cross the brain-blood barrier [4]. Prof. Grattan explained that this was probably the rationale for bilastine not being sedating and showing comparable values to placebo in further studies. These data were confirmed in a clinical study of driving ability under bilastine, which also demonstrated good tolerability [5].

For patients who do not respond to antihistamine therapy, even in combination with second-line therapy, immunomodulatory therapies are available in third-line therapy. This is often the case in patients with chronic spontaneous urticaria with autoantibody detection. In this setting, Prof. Grattan presented study results on omalizumab. Omalizumab is an antibody that binds soluble IgE antibodies in the blood and interstitium before they can bind to their receptors on mast cells. It is a form of therapy to be administered subcutaneously on a monthly basis, which has already been used successfully for several years in severe allergic asthma. In the phase III ASTERIA II trial, omalizumab was shown to be effective for the treatment of chronic spontaneous urticaria, significantly relieving itching in particular [6]. Thereby, the score on the 21-point Itch Severity Scale was reduced by 5.9 under 75 mg omalizumab, by 8.1 under 150 mg, and by 9.8 under 300 mg. This compared with placebo, which achieved a reduction of 5.1 points.

Targeted therapy – the future of urticaria management

The importance of subtyping chronic spontaneous urticaria for the outcome of treatment is also illustrated by the data presented by Oliver Hausmann, MD, Allergology and Clinical Immunology, Inselspital Bern and ADR-AC GmbH, Bern. Targeted Therapy is the keyword here. He presents the “basophil activation test” (BAT), which helps to better understand the pathomechanism of urticaria on an individual level. In addition, the test could thus also allow a more differentiated therapy and a statement on the prognosis.

Conclusion

New evidence already incorporated into the guidelines and new agents are improving patient outcome in urticaria. The development towards targeted therapy is well on its way due to improved diagnostics and will hopefully bring corresponding successes, as in other medical indications.

Literature list at the publisher

Sonia cheerful

Source: Annual Meeting of the Swiss Societies of Allergology and Immunology (SGAI) and Pneumology (SGP), April 17-19, 2013, Bern.