Antidepressants are prescribed too often – contrary to the study evidence, which attests only low efficacy of the commonly used agents in mild depressive episodes, and contrary to the guideline recommendations. When does it make sense to use it?

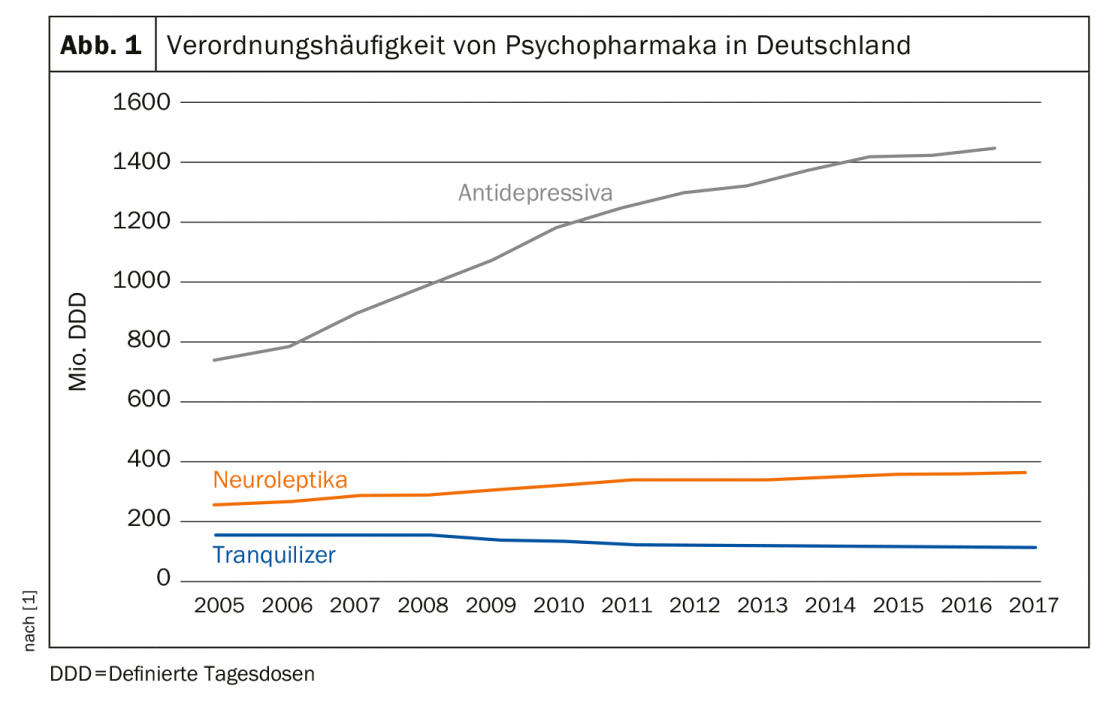

The prescription frequency of antidepressants has doubled in Germany since 2005. This is the conclusion of the 2018 Prescription Drug Report (Fig. 1) [1]. This trend is also evident in other Western industrialized countries, including Switzerland. About 40% of those seeking treatment for mental health problems take antidepressants, women twice as often as men [2]. In the U.S., the numbers are almost frightening: 12% of all U.S. adults over the age of twelve take a psychotropic drug permanently, mostly from the group of antidepressants. On 125. Congress of the German Society for Internal Medicine, Prof. Dr. Gerhard Gründer of the Central Institute for Mental Health in Mannheim therefore warned against unreflected use. This is because the not infrequent discontinuation phenomena, which are still not taken seriously enough and can unintentionally lead to long-term therapy, are also problematic.

Tripling of cases of illness

Antidepressants are the most commonly prescribed psychotropic drugs. One reason for this may be the increasing number of patients – and the fact that more and more people are talking about their mental illness. The DAK Health Report 2019 states a threefold increase in sick days and cases over the last twenty years. The lion’s share of mental disorders is depressive episode (64.9%) or recurrent depressive disorder (28.4%), followed by reactions to severe stress and adjustment disorders (51.4%). There are gender-specific differences: women are affected more frequently than men. For women, the list of complaints is headed by problems of the musculoskeletal system, closely followed by mental illness. Men also fall ill primarily in the musculoskeletal system, with psychological complaints coming only in third place. However, the number of unreported cases of mental illness is probably higher, especially since these can sometimes “hide” behind somatic symptoms. If one relates the cases of sick leave to the days of sick leave, then not only an increased frequency of sick leave can be observed with higher age, but also a longer duration of sick leave [3]. Given these numbers, the inhibition to prescribe a psychotropic drug is low among some specialists and primary care providers. The hope: rapid help for the patient. But what do studies say about the effect size of antidepressants?

The effectiveness is overestimated

In the largest network analysis to date, Cipriani and colleagues compared 21 antidepressants based on 522 placebo-controlled trials and head-to-head studies with a total of 116 477 participants [4]. The meta-analysis showed: All tested active substances have a significantly better efficacy than placebo. However, the effect size is relatively small. “Psychiatrists also tend to somewhat overestimate the effectiveness of antidepressants,” comments Prof. Gründer. Another observation of the meta-analysis was that new substances always performed better than those that were already somewhat older and served as reference substances. In the head-to-head comparison, escitalopram, mirtazapine, paroxetine, agomelatine, and sertraline in particular stood out for a relatively high response with a low dropout rate. In contrast, reboxetine, trazodone, and fluvoxamine had lower efficacy and acceptability profiles.

The above data refer to antidepressants used to treat adults suffering from depression. But what about the effectiveness of antidepressants in children and adolescents? “Here, the effectiveness is usually even more modest,” says Prof. Gründer. “No antidepressant is significantly better than placebo”. With one exception: fluoxetine. The active ingredient is therefore the only one approved for the treatment of depression in children and adolescents. Nevertheless, other substances are also used therapeutically in this patient group.

Severity and placebo probability

The power of the so-called “placebo effect” was demonstrated, among other things, in a double-blind study that examined the efficacy of sertraline and mirtazapine in depressed dementia patients in a placebo comparison. After 39 weeks, it turned out that the administration of placebo pills led to a reduction in depressive symptoms that was just as good as the administration of one of the two active substances [5]. However, this finding should in no way be taken as a call to treat patients only with placebo in the future. Rather, he suggests that placebo is “not just the sugar pill, but treatment context.”

Indeed, the efficacy of substances seems to have something to do with the patient’s expectations. For example, a recently published study found that the efficacy of an antidepressant was influenced by whether the patient expected to receive the verum – or a placebo. The lower the probability of receiving a placebo, the higher the efficacy of the antidepressant tested and the lower the dropout rate. In other words, the effectiveness of the antidepressant depends critically on the context [6].

While everyone agrees on this, the question of the influence of the severity of the disease remains. In a 2008 metastudy, Kirsch and colleagues pointed to a positive correlation between depression severity and antidepressant efficacy. There was no significant efficacy over placebo for mild depression, but there was for severe depression [7]. However, Prof. Gründer puts this finding into perspective by referring to larger meta-analyses in which no dependence on severity was found: “The finding stands like this”.

What do the guidelines say?

What remains is to look at the treatment recommendations [8]. There, too, context is important, for example in the form of trust between patient and practitioner. The S3 guideline of the DGPPN also states that pharmacotherapy must be embedded in a conversation offer from the beginning. It is also emphasized that the use of antidepressants in the initial treatment of mild depressive episodes is not indicated because of the unfavorable risk-benefit ratio, especially since antidepressants do not show significant superiority compared with placebo. Particularly if the patient with mild depressive symptoms does not wish to receive drug therapy or if relief can be achieved without antidepressants, the guideline recommends “active-waiting monitoring” with a further review within the following two weeks. Medication intervention even for mild depressive episodes is warranted if symptoms persist after other forms of therapy, the preceding depressive episodes were at least moderate in severity, or the patient specifically requests intervention. The use of antidepressants is indicated for moderate to severe depressive episodes. For Prof. Gründer, too, it is ultimately the severity of the depression that determines whether an antidepressant should be used.

Source: DGIM 2019, Wiesbaden (D)

Literature:

- Schwabe U, et al: Drug prescription report 2018. Current data, costs, trends and comments. Berlin: Springer, 2018.

- Schuler D, et al: Mental health in Switzerland. Monitoring 2016. Obsan Report 72. Swiss Health Observatory, 2016.

- Storm A, ed: Health report 2019. analysis of work disability data. Old and new addictions in the workplace. Heidelberg: medhochzwei, 2019.

- Cipriani A, et al: Comparative efficacy and acceptability of 21 antidepressant drugs for the acute treatment of adults with major depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet 2018; 391(10128): 1357-1366.

- Banerjee S, et al: Sertraline or mirtazapine for depression in dementia (HTA-SADD): a randomised, multicentre, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 2011; 378(9789): 403-411.

- Salanti G, et al: Impact of placebo arms on outcomes in antidepressant trials: systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2018; 47(5): 1454-1464.

- Kirsch I, et al: Initial Severity and Antidepressant Benefits: A Meta-Analysis of Data Submitted to the Food and Drug Administration. PLoS Med 2008; 5(2): e45.

- DGPPN, ed.: S3-Leitlinie Unipolare Depression. Long version. 1st edition, version 5.

- Kelly CM, et al: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and breast cancer mortality in women receiving tamoxifen: a population based cohort study. BMJ 2010; 340: c693.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2019; 17(4): 29-30 (published 6/20/19; ahead of print).