Patched is not cured: Patients with congenital heart defects are at high risk for heart defect-related complications in adulthood. Specialized, structured, and interdisciplinary follow-up can mitigate the risk of complications and improve survival. Tachycardia is the most common complication in adulthood. Atypical atrial flutter (intraatrial scar reentry tachycardia) is particularly common. Atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction can lead to tachymyopathy within a few days! Due to increased pulmonary valve replacement with bioprostheses, the incidence of endocarditis is steadily increasing. Good patient education and awareness among primary care providers regarding cardiovascular complications (especially arrhythmias and endocarditis) is important and can make a significant contribution to reducing morbidity and mortality.

Depending on the definition and type of epidemiological survey, a congenital heart defect is found in about 1-2% of all newborns. Thus, these are the most common congenital malformations [1,2]. Without intervention, most patients with complex congenital heart defects do not survive into adulthood [3]. However, with the development of modern cardiac surgery, this has changed dramatically, and the vast majority of patients now survive into adulthood [4]. This has led to a rapid increase in the number of adults with congenital heart defects over the past decades [5]. These individuals may not be considered “cured.” Many have residual hemodynamic lesions (e.g., valvular stenosis or insufficiency) with a significantly increased risk of morbidity and mortality in adulthood [6]. Recent studies have shown that multidisciplinary long-term care at specialized centers can significantly reduce this increased morbidity and mortality [7,8].

The goal of continuous, specialized and individualized follow-up of adults with congenital heart defects is to avoid complications if possible or at least to detect them at an early stage in order to improve the long-term prognosis of the affected patients. The following article is intended to provide an overview of the conditions that make such specialized follow-up possible.

Organizational and structural requirements

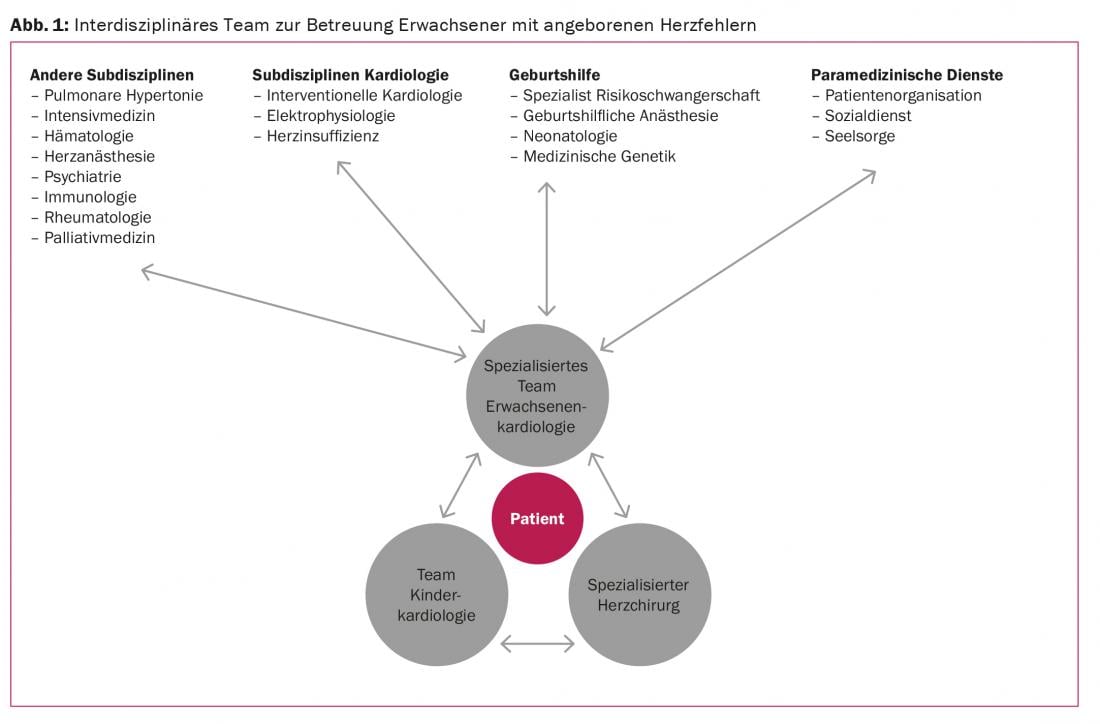

Continuous care at specialized centers is recommended for optimal management of adults with congenital heart defects [9]. At www.sgk-watch.ch you will find information on the specialized centers for adults with congenital heart defects in Switzerland. The core team in providing care consists of specially trained adult cardiologists in close collaboration with pediatric cardiology specialists and specialized cardiac surgeons. In addition, to meet the diverse needs of this complex group of patients, close interdisciplinary networking far beyond the boundaries of cardiology is essential. Figure 1 provides an overview of the teams involved in the care of adults with congenital heart defects.

Follow-up procedures and complications at a glance

Because of residual, hemodynamically unfavorable lesions, many affected patients are at increased risk for arrhythmias, development of heart failure, or endocarditis. Many patients require repeat surgeries or procedures during adult life. The goal of a follow-up procedure is either to improve symptoms or to reduce the risk of any future complications (heart failure, arrhythmias, aortic dissection). Timing of re-operation or re-intervention is often difficult, and a decision must be made on an individual basis. It should be noted that many of the patients affected are still very young. The decision to intervene therefore always requires careful consideration of the expected benefits and any negative long-term consequences.

A prime example is the indication for prosthetic pulmonary valve replacement in patients with severe pulmonary regurgitation after repair of tetralogy of Fallot. After several studies showed that after pulmonary valve replacement, normalization of the dimensions of the right ventricle becomes unlikely above a certain level of dilatation, the indication for pulmonary valve replacement – even in asymptomatic patients – became very liberal. However, no study to date has demonstrated that a dilated right ventricle has prognostic significance and that the prognosis of these patients actually improves after pulmonary valve replacement. In everyday life, however, complications are increasingly seen in patients with pulmonary valve prostheses. These include the need for repeated follow-up procedures and a significantly increased risk of endocarditis. Thus, the prognostic benefit of early pulmonary valve replacement remains highly controversial and needs to be better investigated in the future.

To clarify such important questions in the future, it is important to record as many patients with congenital heart defects as possible in prospective registries. Such a registry has been operated in Switzerland by the university centers for congenital heart defects since 2014. Ideally, non-university centers should also contribute to this registry.

Many affected women with congenital heart defects are of childbearing age. Depending on the type of cardiac defect and hemodynamic residuals, the risk of pregnancy and delivery may be significantly increased [10]. Early, individualized counseling regarding pregnancy risks and contraception must be an integral part of long-term care and must begin in adolescents (see also article “Pregnancy and Birth in Congenital Heart Disease – Relevant to Practice”).

Structured follow-up to improve long-term results

The goals of structured follow-up of adults with congenital heart defects are, on the one hand, the prevention of complications (Table 1) and, on the other hand, the rapid detection of complications and their prompt and adequate treatment, which is crucial for the long-term well-being of patients. It is important to sensitize patients and primary care providers to the typical symptoms of a complication and the adequate behavior when such symptoms occur. The importance of repetitive, structured education of patients regarding symptoms of cardiac arrhythmias and endocarditis can hardly be given enough attention!

Most important apparative examination methods

In addition to a careful history and clinical examination, most adults with congenital heart defects require serial imaging studies, stress testing, and laboratory testing. A detailed account of structured follow-up in patients with congenital heart defects is, of course, beyond the scope of this review. Rather, some specific aspects and pitfalls will be pointed out.

Electrocardiogram (ECG)

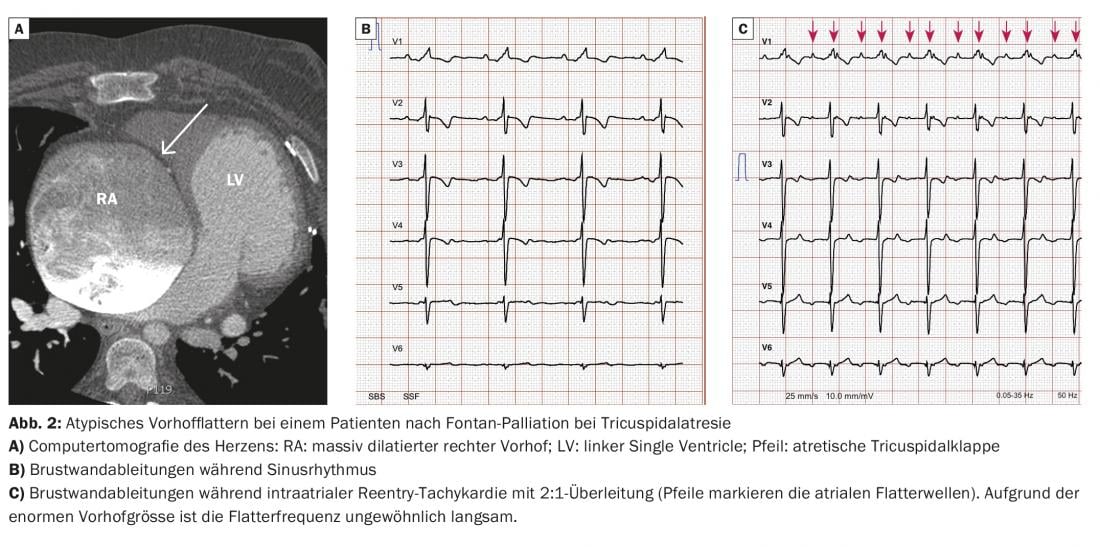

The conventional 12-lead ECG remains an indispensable part of cardiac rhythm diagnostics. Further, the width of the QRS complex, for example, has been shown to have important prognostic significance for some types of congenital heart defects. Because arrhythmias and especially atypical atrial flutter (atrial scar reentry tachycardia) are by far the most common complication in adults with congenital heart defects, we recommend a very liberal derivation of an ECG in cases of palpitations of any kind or sudden unexplained decrease in physical performance. Atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction can lead to the development of tachymyopathy very quickly due to the rigid frequency profile and must definitely be detected and treated in time. To avoid patients presenting late, repetitive patient education plays an important role. In severely dilated atria, a common finding in adults with congenital heart defects, atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction often manifests with an unusually low ventricular rate; therefore, atrial flutter is not infrequently missed! Figure 2 shows the ECG of a patient after Fontan palliation with atypical atrial flutter with 2:1 conduction. These patients often tolerate the loss of sinus rhythm particularly poorly, and in most cases rapid cardioversion must be attempted.

Echocardiography

Transthoracic echocardiography is the most important imaging modality in the follow-up of adults with congenital heart defects. Because of the often complex anatomy and the surgical and interventional procedures that have taken place, a systematic approach to echocardiography is essential.

The description of the basic anatomy follows a fixed structure (sequential anatomy), starting with the definition of the atrial situs (normal arrangement, situs inversus, heteroataxias), followed by the definition of the atrio-ventricular and ventriculo-arterial connections, and finally a systematic description of all associated defects and variants. Because in adulthood the cardiac anatomy of most patients with complex heart defects has been modified by surgical repair procedures, close study of surgical reports often helps in understanding them. These should be available whenever possible. Often copies of these reports are kept in the archives of specialized surgical centers for decades, and it is worth trying to request them in any case. In addition to understanding the exact anatomy, changes in findings over time are often important parameters for decision making regarding follow-up interventions. Serial, careful evaluation of functional parameters is therefore important.

Other examination methods

Depending on the type of cardiac defect and residual findings, advanced imaging with cardiac computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging may be required. For simpler questions (e.g., after pseudoaneurysms in patients with repaired aortic isthmic stenosis), these examinations can also be performed by nonspecialized centers. For complex issues, it is recommended that specialists investigate. This is especially true when serial measurements (e.g., ventricular volumes in patients with repaired tetralogy of Fallot) are needed for decision making regarding follow-up interventions.

Literature:

- Hoffman JI, Kaplan S: The incidence of congenital heart disease. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2002; 39(12): 1890-1900.

- van der Linde D, et al: Birth prevalence of congenital heart disease worldwide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2011; 58(21): 2241-2247.

- Warnes CA, et al: Task force 1: the changing profile of congenital heart disease in adult life. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2001; 37(5): 1170-1175.

- Moons P, et al: Temporal trends in survival to adulthood among patients born with congenital heart disease from 1970 to 1992 in Belgium. Circulation 2010; 122(22): 2264-2272.

- Marelli AJ, et al: Lifetime prevalence of congenital heart disease in the general population from 2000 to 2010. Circulation 2014; 130(9): 749-756.

- Greutmann M, et al: Increasing Mortality Burden among Adults with Complex Congenital Heart Disease. Congenital heart disease 2015; 10(2): 117-127.

- Wray J, et al: Adult congenital heart disease Research N: Loss to specialist follow-up in congenital heart disease; out of sight, out of mind. Heart 2013; 99(7): 485-490.

- Mylotte D, et al: Specialized adult congenital heart disease care: the impact of policy on mortality. Circulation 2014; 129(18): 1804-1812.

- Baumgartner H, et al: ESC Guidelines for the management of grown-up congenital heart disease (new version 2010). European heart journal 2010; 31(23): 2915-2957.

- ESC Guidelines on the management of cardiovascular diseases during pregnancy: the Task Force on the Management of Cardiovascular Diseases during Pregnancy of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). European heart journal 2011; 32(24): 3147-3197.

CARDIOVASC 2015; 14(3): 13-16