In addition to providing expert opinions in all areas of law, Forensic Psychiatry is entrusted with the treatment of mentally ill lawbreakers. This task at the interface between law and psychiatry requires special knowledge. Criminal law aspects deal with the assessment of culpability and treatment in the correctional system.

In addition to providing expert opinions in all areas of law, Forensic Psychiatry is entrusted with the treatment of mentally ill lawbreakers. This task at the interface between law and psychiatry requires special knowledge, which is why there is a corresponding focus title with specific training and continuing education requirements. The present article deals exclusively with aspects of criminal law, specifically with the assessment of culpability and treatment in the custodial system.

Expert opinion on culpability

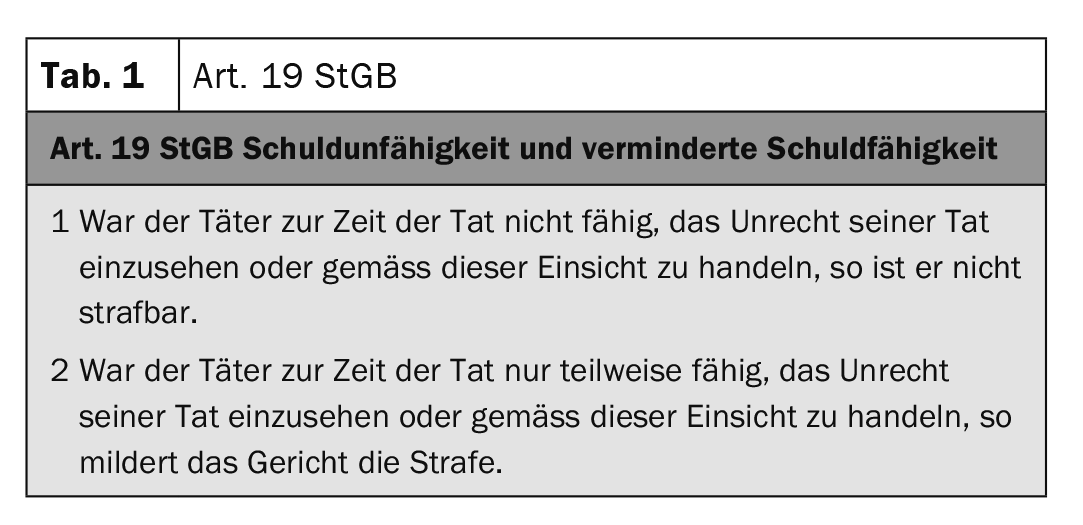

The accusation of guilt is linked to the ability of self-determination and the freedom of the human will [1]. If there are doubts about this, for example due to the existence of a mental disorder, this justifies the involvement of a forensic psychiatric specialist for the purpose of an expert assessment. The legal bases for culpability are laid down in Art. 19 StGB (Table 1).

An existing mental disorder as a prerequisite for the reduction of guilt is not explicitly mentioned in the text of the law, but according to the prevailing doctrine it is implicitly the basis of further examination steps [2]. Accordingly, in the first diagnostic-normative stage, the culpability assessment addresses the question of whether a serious mental disorder is present. The decisive factor here is the degree of functional impairment present at the time of the crime [3].

In the second step, it is to be examined whether symptoms can be determined from the psychiatric disturbance pattern that are close to the time of the crime and have led to impairments of the ability to see and control. The term insightfulness addresses knowledge of legal norms and their validity. Abolished capacity for insight can be caused, for example, by reductions in intelligence or psychotic disorders that remove the connection to reality. The ability to control refers to the individual’s ability to direct his or her actions in accordance with the insight he or she has gained into wrongdoing. This also requires the ability to reject or inhibit impulses to act. It is not always possible to draw an exact line between the capacity for insight and the capacity for control. Commits e.g. a person suffering from schizophrenia commits a delusionally motivated offense, the delusional experience may also have distorted the person’s value structure, which may override the ability to reason [4]. However, a delusion also endangers the ability to control action, because a high level of delusional dynamics can cause a suspension of the ability to control. The assumption that preserved action control can be derived from planning and orderly action is therefore not valid.

|

Case study A 30-year-old man suffering from schizophrenia obtains utensils to build an incendiary bomb (Molotov cocktail). He throws the incendiary device into a nearby police station days later. During interrogation, he states that police officers assigned to the station have been watching, listening to and harassing him for months. He said he couldn’t take it anymore and wanted to put an end to “it all.” In this case, the psychotic symptoms lead to the assumption that the motivational control capacity has been suspended. |

Assessment of the risk of recidivism: the criminal prognosis

The careful assessment and evaluation of the offender’s personality is at the center of the criminal prognostic assessment [5]. With special consideration of the interplay of psychopathological abnormalities, a delinquency hypothesis is formulated. Taking into account statistical and dynamic risk factors, statements are made with regard to the future risk of delinquency of the persons concerned. The Federal Statistical Office provides information on the base rate of reconvictions in relation to different offense categories [6]. Based on this baseline rate, the risk of relapse increases in the presence of additional risk factors. These include male gender, low socioeconomic status, homelessness, and substance abuse, as well as unstable employment and criminological factors such as previous violent offenses or incarceration [7]. Mental illnesses, e.g. from the schizophrenic group, can also have a negative effect on the risk prognosis [8].

The (statistical) risk forecast is supplemented by so-called Structured Professional Judgements (SPJ). In contrast to statistical risk instruments, this does not assign point values, but identifies needs in terms of required risk management [9]. The HCR-20 is the best-studied SPJ instrument, capturing 20 risk factors for future violent behavior across three domains [10]: past problems (“history” [H]), clinical variables (“clinical” [C]), and future risks (“risk” [R]). Based on problem areas assessed as relevant, risk scenarios are designed under various framework conditions (dismissal, leave of absence, etc.) in order to be able to make statements on the required risk management. In this context, not only the clinical influenceability of a corresponding symptomatology, but also the willingness of the affected persons to cooperate and the social reception space have an influence on the prospects of success [19].

|

With regard to the case presented, it should be noted that the risk prognosis of the person concerned was already preloaded: he suffered and still suffers from paranoid schizophrenia, i.e. a severe underlying mental illness. From the existing delusion symptomatology, a close connection between illness-related experience and the crime can be deduced. At the time of the offense and for months before, he was without psychiatric treatment and was not taking medication. Regular cannabis use further burdens his risk prognosis. During a general psychiatric inpatient stay months earlier, he attacked a fellow patient by whom he had allegedly felt harassed, so there is already a history of violent acts. The individual lives alone, has no daily structure, and reports no social support from friends or relatives – these factors also have an unfavorable risk prognostic effect. |

Treatment measures

Measure treatments are ordered when punishment is not sufficient to address the risk of recidivism. Forensic psychiatric treatment measures thus primarily serve to improve the legal prognosis. In contrast to Germany, the impairment of culpability is not a prerequisite for the ordering of a therapeutic measure in Switzerland [11]. In addition to the risk of relapse, treatment prospects, treatment readiness, and feasibility are relevant. In 2021, 200 inpatient and 279 outpatient measures were ordered in Switzerland [12]. In contrast to general psychiatric practice, here it is not the patient who formulates the treatment wish, but the treatment setting is legally decreed. It is understandable that this constellation influences the doctor-patient relationship [13].

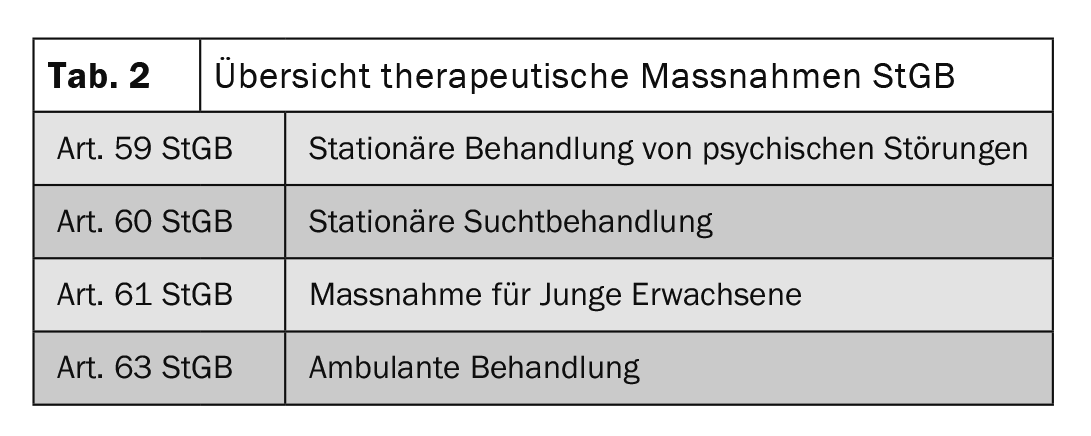

The inpatient execution of the therapeutic measure is not always necessary; a measure can also be carried out in an outpatient setting. If this happens during the execution of a custodial sentence, the outpatient measure can be carried out alongside the execution of the sentence. Suitable facilities for the implementation of inpatient correctional measures are forensic psychiatric clinics, specialized departments of correctional institutions or correctional centers. For young adults, there are facilities that address the inmates’ independence and assumption of responsibility; there is a comprehensive range of training programs to promote personal development (Table 2).

The custody acc. Art 64 StGB also belongs to the measures, but does not pursue a therapeutic mission. It can be ordered, among other things, if a so-called catalog crime has been committed, e.g. serious bodily injury or rape. The goal of custody is not resocialization, but the protection of the public.

Treatment within the framework of therapeutic measures is oriented toward the individual recidivism risk for committing new crimes and addresses corresponding risk factors as well as the responsiveness of offenders (so-called Risk-Need-Responsivity Model [14]). The goal is to help them lead socially acceptable lives (Good Lives Model [15]).

|

In the case described, the delusional experience and the associated risk of reoffending cannot be reduced by imprisonment. Psychiatric treatment is needed to address this constellation of risk. Previous psychiatric treatment of the expl. show that his delusion symptomatology relevant to delinquency remits well under antipsychotic medication, only it also showed that there were recurring problems with regard to the Expl.’s ability to cooperate. gave: He repeatedly discontinued his medication on his own authority and failed to show up for appointments. He was also currently not willing to take medication again, so that the treatment of measures does not seem promising in an outpatient setting, but only in an inpatient setting. |

Data from Germany impressively show that treatment in a correctional facility is associated with lower recidivism rates than after release from prison: Approximately one third of released forensic patients (35.2%) committed new crimes within a long catamnesis period (16.5 years on average), 12.8% committed serious violent or sexual offenses, and only one in six patients (15.6%) was re-imprisoned. [16]. In contrast, persons after serving a prison sentence without parole showed a general recidivism rate of 47% and 28%, respectively, related to sexual offenses within a significantly shorter observation period (6 years) [17].

Take-Home Messages

- Forensic psychiatric work requires specialized knowledge.

- Assessment questions address the legal implications of mental disorders.

- Intervention treatments serve to reduce the risk of relapse, and this goal is achieved for a large proportion of those affected.

Literature:

- Habermeyer E, Hoff P: On the forensic application of the concept of insight capacity. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr. 2004;72(11): 615-620.

- Habermeyer E, Mokros A, Briken P: “The relevance of a coherent forensic assessment and treatment process”: big deal or old wine in leaky hose? Forensic psychiatry, psychology, criminology. 2020;14(2): 212-219.

- Rosenau H: Chapter 8 – Legal foundations of psychiatric assessment. In: Foerster V, Habermeyer D, Dreßing H, Habermeyer E, Bork S, Briken P, et al, editors. Psychiatric assessment (Seventh edition). Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2020: 85-150.

- Lau S, Kröber H-L: The culpability opinion. In: Kröber H-L, Dölling D, Leygraf N, Sass H, editors. Handbook of forensic psychiatry: psychopathological principles and practice of forensic psychiatry in criminal law. Heidelberg: Steinkopff; 2011: 213-560.

- Habermeyer E: Forensic psychiatry. The Neurologist 2009; 80(1): 79-92.

- Criminal Sentencing Statistics 2018 [Internet]. Federal Statistical Office. 2020. Available from: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kriminalitaet-strafrecht/rueckfall.assetdetail.11527036.html.

- Whiting D, Fazel S: Epidemiology and Risk Factors for Violence in People with Mental Disorders. In: Carpiniello B, Vita A, Mencacci C, editors. Violence and Mental Disorders. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2020: 49-62.

- Whiting D, Lichtenstein P, Fazel S: Violence and mental disorders: a structured review of associations by individual diagnoses, risk factors, and risk assessment. The Lancet Psychiatry 2021; 8(2): 150-161.

- Hart S, Douglas K, Guy L: The structured professional judgment approach to violence risk assessment: origins, nature, and advances. 2016: 643-666.

- Douglas KS, Hart SD, Webster CD, et al: Historical-Clinical-Risk Management-20, Version 3 (HCR-20V3): Development and overview. The International Journal of Forensic Mental Health. 2014;13(2): 93-108.

- Habermeyer E, Dreßing H, Seifert D, et al: Praxishandbuch Therapie in der Forensischen Psychiatrie und Psychologie: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2021.

- Execution of measures: admissions by type of measure [Internet]. 2021. Available from: www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/de/home/statistiken/kriminalitaet-strafrecht/justizvollzug.assetdetail.19744601.html.

- Meyer M, Hachtel H, Graf M: Special features of the therapeutic relationship in forensic psychiatric patients. Forensic psychiatry, psychology, criminology. 2019;13(4): 362-370.

- Bonta J, Andrews DA: Risk-need-responsivity model for offender assessment and rehabilitation. Rehabilitation. 2007;6(1): 1-22.

- Franqué Fv, Briken P: The Good Lives Model (GLM). Forensic psychiatry, psychology, criminology. 2013; 7(1): 22-27.

- Seifert D, Klink M, Landwehr S: Recidivism data of treated patients in the Maßregelvollzug according to § 63 StGB. Forensic psychiatry, psychology, criminology. 2018; 12(2): 136-148.

- Jehle JM, Albrecht HJ, Hohmann-Fricke S, Tetal C: Legal probation after criminal sanctions: a nationwide recidivism survey 2010 to 2013 and 2004 to 2013. 2016: Forum Verlag Godesberg GmbH.

InFo NEUROLOGY & PSYCHIATRY 2022; 20(4): 8-10.