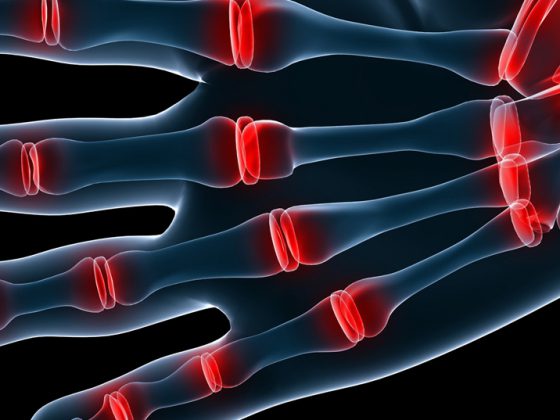

How to evaluate and treat osteoporosis depends on several prerequisites: First, one should individually assess which risk factors a patient has for the development of osteoporosis or for so-called fragility fractures as a whole. Furthermore, age plays a role, of course, but also gender, as well as menopausal status and other secondary associated processes. At the EULAR congress in Paris, various options for diagnosis, prophylaxis and therapy were discussed.

Pilar Peris Bernal, MD, Barcelona, pointed out that osteoporosis in men is often associated with secondary causes. In the laboratory, serum calcium and phosphate, alkaline phosphatase, complete blood count, ferritin, liver and kidney function values, protein electrophoresis, 24-h urine calcium, 25-hydroxy vitamin D, and testosterone can be obtained. In addition, so-called “bone turnover markers” can be analyzed. Diagnostic tools include bone densitometry, spinal radiography, and, of course, clinical history and physical examination (height/weight). “The diagnosis of osteoporosis includes a T-score of <-2.5,” explained Dr. Peris Bernal.

For diagnosis, it should generally be kept in mind that some types of secondary osteoporosis (such as the glucocorticoid-induced form) show fractures with higher bone mineral density values, and that other metabolic bone diseases (e.g., osteomalacia) can in turn easily lead to confusion in the differential diagnosis.

Prophylaxis and therapy

According to Dr. Peris Bernal, the choice of the right pharmacological treatment, i.e., the type of antiosteoporotic agent, the administration route, the optimal duration and monitoring of therapy, depends on individual patient characteristics and fracture risk. “For example, while bisphosphonates are commonly used in postmenopausal women and men with osteoporosis, they should be used cautiously in premenopausal patients. Additional nonpharmacologic options such as percutaneous vertebroplasty for the treatment of painful vertebral fractures also require appropriate patient selection,” she said. Important risk factors for new vertebral fractures are, for example, not only a low 25-OH vitamin D level (<20 ng/ml) or increasing age, but also the number of percutaneous vertebroplasties (>1). Thus, according to Dr. Peris Bernal, vertebroplasty should be used only in selected patients with persistent symptomatic vertebral pain and without sufficient response to conservative therapy. “However, these patients should also receive targeted osteoporosis therapy and correction of vitamin D deficiency,” she said.

The basic prerequisite for osteoporosis therapy, but also for osteoporosis prophylaxis, is an adequate vitamin D and calcium balance and abstinence from alcohol and tobacco. “Recommended calcium intakes for adults over 50 years of age (including postmenopausal women) are 1200 mg/tgl. and a vitamin D level of at least 50 nmol/l. It has been shown that many Europeans – especially those with rheumatic complaints – do not reach this minimum value and even have a severe deficiency [1,2]”, says Dr. Peris Bernal.

In male idiopathic osteoporosis, bisphosphonates, teriparatide and denosumab are also used. For secondary male osteoporosis may be considered:

Hypogonadism: hormone therapy, bisphosphonates, teriparatide, denosumab.

Glucocorticoid-induced: Bisphosphonate, teriparatide.

Alcoholism: abstinence from alcohol.

“Hormone therapy is specifically indicated in young men with associated symptoms and, of course, no contraindications,” Dr. Peris Bernal said.

Premenopausal women

Osteoporosis is also frequently associated with secondary causes in premenopausal women. In the laboratory, again the above values (instead of testosterone 17-β-estradiol) can be obtained. In principle, there are rather few studies on the possible therapeutic options in this population.

Therapeutic approaches here also include adequate vitamin D and calcium balance, exercise, and abstinence from alcohol and tobacco. Thereafter, the possibly associated disease or hypogonadism is treated and only then any specific drug therapy is considered.

“In a retrospective study [3] of idiopathic young osteoporosis patients (premenopausal), we investigated the effect of a conservative approach (vitamin D/calcium and exercise) on bone mineral density,” said Dr. Peris Bernal. “On average, the follow-up period was three years. Bone mineral density at the lumbar vertebrae and femoral neck was collected at baseline and then annually. Patients had one or more fragility fractures and/or a Z-score <-2. We had ruled out secondary causes in all patients. In fact, calcium and vitamin D treatment and increased physical activity showed a clear effect on bone mineral density: it increased significantly after two and three years. Thereby, no new skeletal fractures were observed during the follow-up period.”

Classical specific-drug therapy should be considered in high-risk patients (with amenorrhea and/or fractures). Bisphosphonates and teriparatide should be used under risk assessment and after careful evaluation of any contraindications. If indicated, consider the use of bisphosphonates with deeper bone retention. In addition, according to Dr. Peris Bernal, contraception is recommended during pharmacological therapy.

“In summary, the therapeutic approach to this condition must always start with the evaluation of the individual fracture risk and general risk factors and, if possible, their reduction, and then, in a second step, if necessary, select the most appropriate osteoporosis drug,” Dr. Peris Bernal summarized.

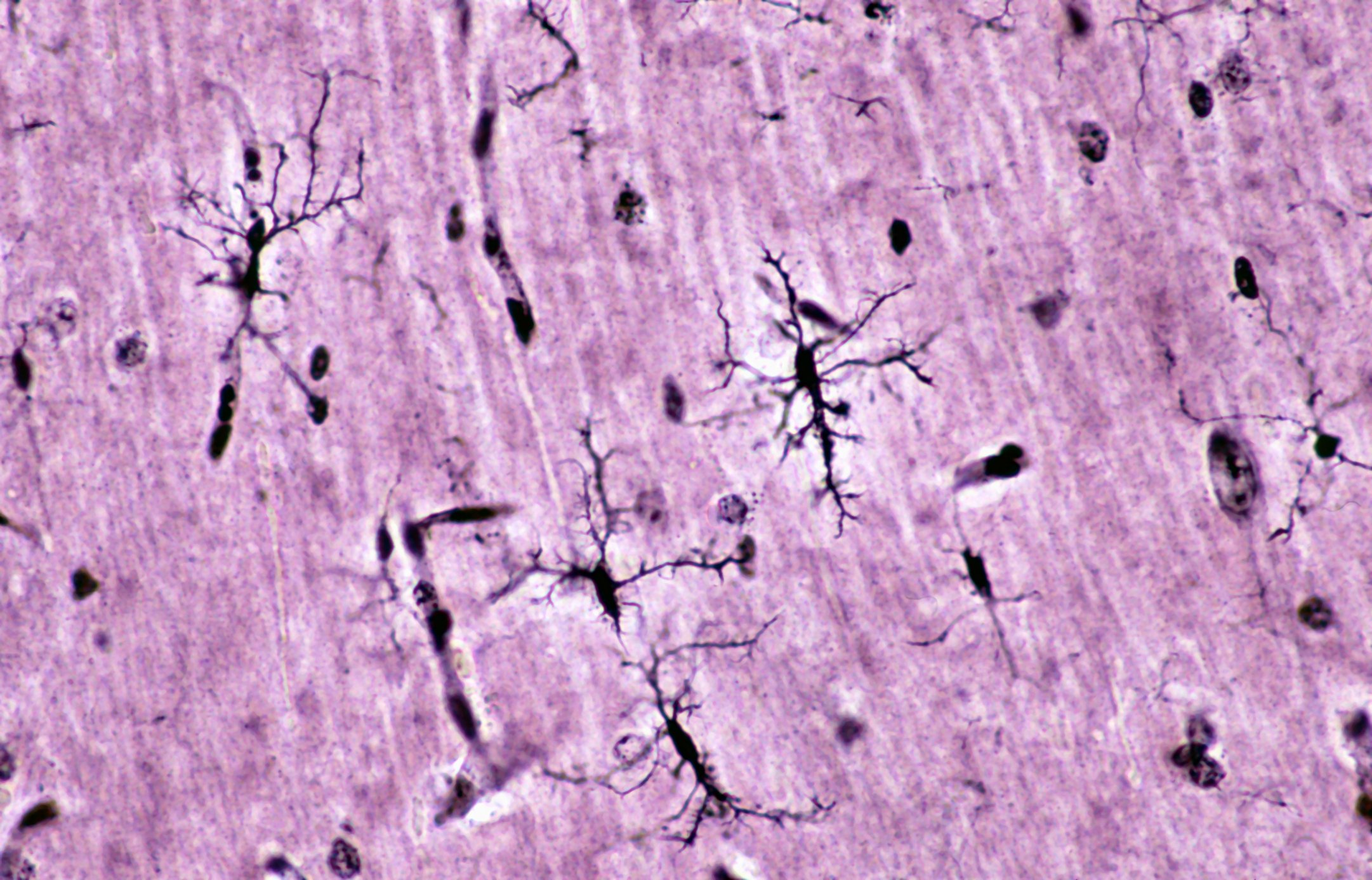

Inhibit bone resorption, maintain signal transduction

Osteoporosis is the result of an imbalance during continuous bone renewal (remodeling): Bone resorption outweighs bone formation. As a result, bone mass decreases, bone structure deteriorates, and fractures become more likely. The enzyme cathepsin K is centrally involved in the degradation of the bone matrix via osteoclasts and is therefore suitable as a therapeutic target. Odanacatib is a specific inhibitor of cathepsin K that has not yet been approved: it blocks bone resorption by cathepsin K but leaves osteoclasts functionally intact and thus does not interfere with signal transduction between osteoclasts and osteoblasts. This is significant because, according to new research, the exchange between the two cell types is fundamental for new bone formation.

According to Prof. Roland Chapurlat, MD, Lyon, clinical studies show that odanacatib continuously increases bone mineral density, reduces bone resorption and maintains bone formation. Bone density is improved in several parts of the body.

What are the clinical data?

The extended follow-up of a phase II study demonstrated long-term success in bone resorption and bone density: 399 postmenopausal women with a T-score between – 2.0 and – 3.5 at the spine and hip participated in the two-year baseline study. They were randomized to receive either placebo or odanacatib once weekly at doses of 3, 10, 25, or 50 mg plus vitamin D(3) and calcium. Results of the prespecified five-year extension phase were published in 2012 [4].

13 patients took odanacatib 50 mg continuously for five years. They achieved a mean “bone mineral density” (BMD) improvement in the lumbar region of 11.9% (vs. – 0.4% for women who switched to placebo after two years). Pooled analysis showed that women who had received odanacatib at doses of 10-50 mg continuously for five years (n=26-29) had a median improvement of nearly 55% in key bone resorption markers. In contrast, marker values for bone formation remained almost the same since baseline. Bone density in the spine and hip increased at the 10-50 mg doses over the five years, with good tolerability of the drug. The effects were reversible, i.e., bone density decreased again after discontinuation, and bone resorption increased.

Brixen et al. confirmed the results in 2013 [5]. In 214 postmenopausal women, odanacatib at the dose of 50 mg/week showed:

- a significant increase (p<0.001) in area-based BMD value of the lumbar spine after one year (3.5% higher than placebo);

- a significantly lower value in the bone resorption marker than with placebo after six months and after two years (p<0.001);

- a value comparable to placebo in the bone formation marker after two years;

- a significant increase (p<0.001) in trabecular volume-related BMD value of the spine and in integral/trabecular volume-related BMD value of the hip after six months (compared with placebo);

- a comparable side effect profile to placebo.

“So again, odanacatib reduced bone resorption and maintained bone formation,” Prof. Chapurlat said. “Treatment with the agent was also found to improve trabecular microarchitecture, cortical thickness, and bone strength in the distal radius and distal tibia [6].”

A phase III trial involving more than 16,000 postmenopausal osteoporosis patients and with the primary endpoint of fracture risk reduction is currently being closed. Based on early observable robust interim efficacy data and a good benefit-risk profile, early discontinuation was recommended in 2012. However, a blinded extension phase is underway. It will provide data from a total period of five years until its completion.

Source: “Osteoporosis,” presentation at EULAR Congress, June 11-14, 2014, Paris.

Literature:

- Haller J: The vitamin status and its adequacy in the elderly: an international overview. Int J Vitam Nutr Res 1999 May; 69(3): 160-168.

- Aguado P, et al: Low vitamin D levels in outpatient postmenopausal women from a rheumatology clinic in Madrid, Spain: their relationship with bone mineral density. Osteoporos Int 2000; 11(9): 739-744.

- Peris P, et al: Bone mineral density evolution in young premenopausal women with idiopathic osteoporosis. Clin Rheumatol 2007 Jun; 26(6): 958-961.

- Langdahl B, et al: Odanacatib in the treatment of postmenopausal women with low bone mineral density: five years of continued therapy in a phase 2 study. J Bone Miner Res 2012 Nov; 27(11): 2251-2258.

- Brixen K, et al: Bone density, turnover, and estimated strength in postmenopausal women treated with odanacatib: a randomized trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013 Feb; 98(2): 571-580.

- Cheung A, et al: Effects of Odanacatib on the Radius and Tibia of Postmenopausal Women: Improvements in Bone Geometry, Microarchitecture and Estimated Bone Strength. J Bone Miner Res 2014 Feb 12. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.2194. [Epub ahead of print].

CONGRESS SPECIAL 2014, 5(2): 36-39