Case report: The family presents with their three-week-old newborn as an emergency case. Already at birth a bluish spot on the face had been noticed, which was thought to be a peripartum hematoma. Since the tenth day of life, similar bluish-reddish spots and plaques would appear all over the body. Her son was born on term after an uneventful pregnancy, showed unremarkable adaptation, and was in regular general condition with good weight gain.

Clinical picture:

In the area of the face, the trunk and to a lesser extent the proximal extremities, a total of about 20 bluish-reddish, relatively sharply demarcated macules and plaques are visible (Fig. 1). The mucous membranes are unremarkable, and no lymphadenopathies or organomegaly are present.

Quiz

Based on this information, which is the most likely diagnosis?

A Mastocytosis (Urticaria pigmentosa)

B “Blue rubber bleb nevus” syndrome

C Hemangiomatosis

D Acute leukemia

E Child abuse

Diagnosis and discussion:

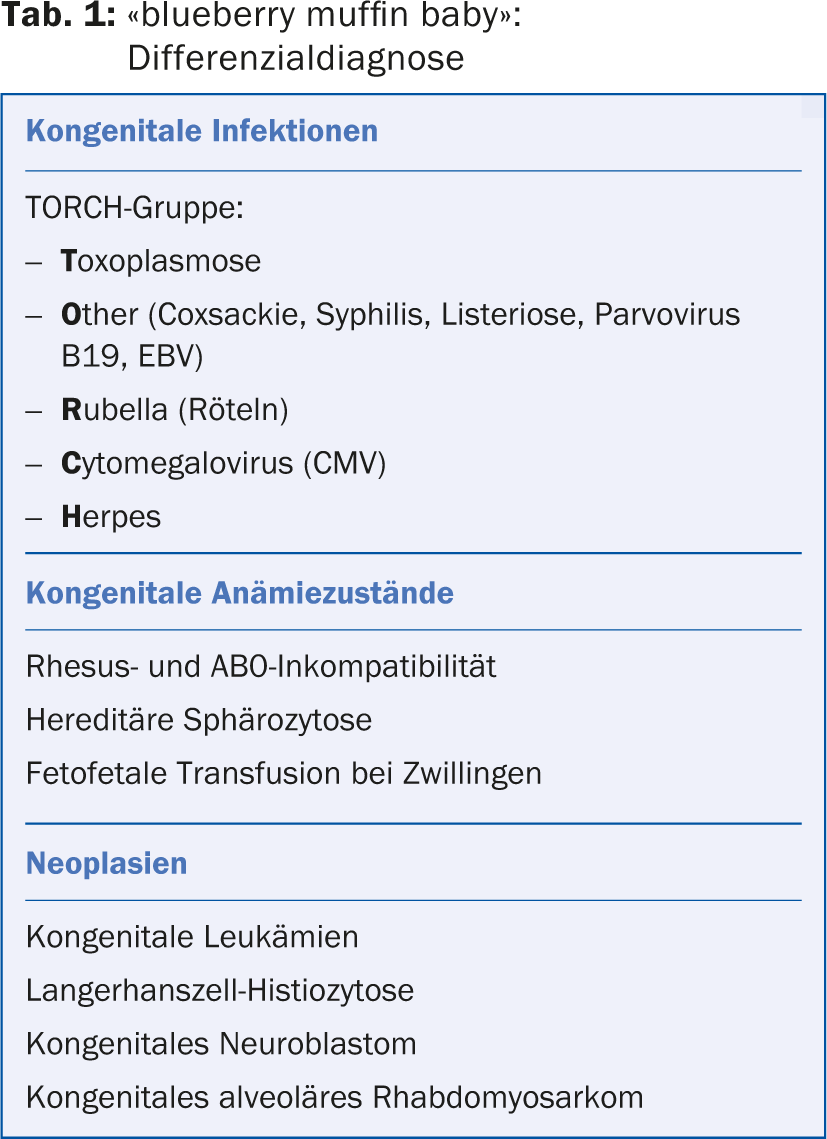

This rare but characteristic clinical presentation with multiple bluish, reddish, or pinkish macules, plaques, or nodules is called a “blueberry muffin baby” given its resemblance to blueberry muffins. It is a phenotype that may be based on various pathologies and is observed exclusively at birth and in the first weeks of life. Classically, compensatory extramedullary hematopoiesis is present in the skin and other organs in the setting of congenital infections or severe anemic states, but the picture may also be due to neoplastic infiltrates (Table 1) [1,2].

Due to the severity of the possible underlying diseases, “blueberry muffin” lesions should be interpreted as an alarm sign and immediate further investigations are indicated. These include a detailed history (signs of infection in pregnancy), clinical status (vital signs, lymphadenopathies, organomegaly), laboratory chemistry tests (differential blood count, chemistry, LDH, hemolysis parameters, serologic workup of congenital infections), skin biopsy, abdominal ultrasonography, and bone marrow and lumbar puncture if necessary.

There was no evidence of congenital infection in our patient and the initial investigations in our emergency department, in particular blood count, chemistry and abdominal ultrasonography, were unremarkable. Only skin biopsy revealed atypical myeloid infiltration compatible with acute myelomonocytic leukemia (M4) (response D). The subsequent bone marrow biopsy showed a blast percentage of 48% and the CSF findings were also positive.

Knowledge of the “blueberry muffin” phenotype as a cutaneous alarm sign is crucial for immediately directing affected newborns and infants to the necessary investigations and possible therapy.

Literature:

- Hodl S, et al: Blueberry muffin baby: the pathogenesis of cutaneous extramedullary hematopoiesis. Dermatologist 2001; 52: 1035-1042.

- Mehta V, Balachandran C, Lonikar V: Blueberry muffin baby: a pictoral differential diagnosis. Dermatol Online J 2008; 14: 8.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2014; 24(5): 36-37