Psoriasis therapy has been significantly expanded in recent years. New substances are continuously entering the market. Merkel cell carcinoma, on the other hand, is a rare skin tumor with a poor prognosis. Positive news is rare here. The AAD Congress was dedicated to both conditions.

Compared to melanoma, Merkel cell carcinoma is much rarer. However, this primary malignant skin tumor is highly aggressive and in many cases fatal, so it should not be forgotten under any circumstances. Especially because the incidence is increasing alarmingly according to a new study presented at the congress and in parallel in JAAD [1].

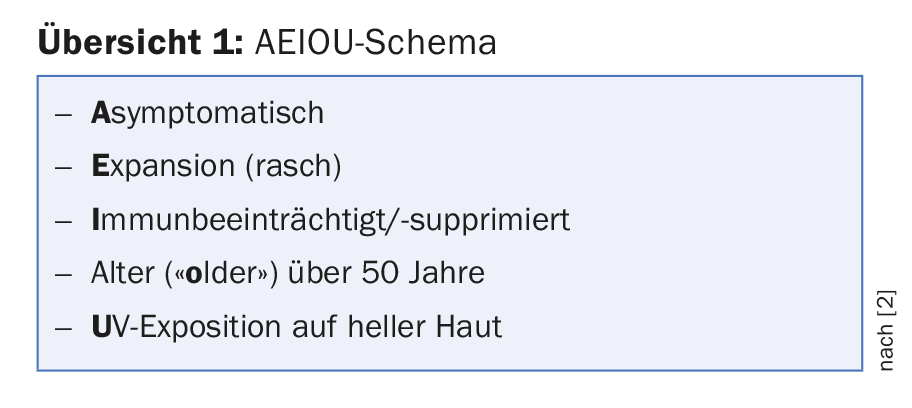

In early stages, Merkel cell carcinoma can still be treated relatively successfully (surgery, radiotherapy). However, growth and metastasis progress rapidly, and although current immunotherapies against PD-1/PD-L1 have made significant progress compared to chemotherapy alone in the past (Avelumab, Bavencio®, has been approved in Switzerland since 2017), metastatic Merkel cell carcinoma is still often fatal in a relatively short time. Early detection is therefore critical. Unlike melanoma, the tumor does not present as a dark spot, but rather as a solid red, purple, or skin-colored nodular lesion that grows relatively rapidly and is otherwise asymptomatic. However, the presentation may vary. Speakers at the Congress referred to the AEIOU scheme (overview 1) [2]. Nearly 90% of primary Merkel cell carcinomas meet three or more of these criteria. Thus, a biopsy is warranted if the signs are combined.

As with other skin tumors, Merkel cell carcinoma particularly affects men, Caucasians, people over 50 years of age, and those with previous skin tumors. Age is of great relevance here: Incidence rates in 60- to 64-year-olds are ten times higher than in 40- to 44-year-olds – and over 85-year-olds are ten times more likely to be affected. The well-known US SEER registry (SEER-18) served as the data basis. The researchers had expected an increase (after all, melanoma incidence has also been rising for decades), but they were surprised by the clarity of the results: from 2000 to 2013, the overall number of cases skyrocketed by 95% (compared with 57% for melanoma). A further increase is expected in the next few years, according to the study authors. Thus, already now the registered cases are increasing faster than in melanoma.

Immune system and UV exposure as reasons

The aging of American society is likely to be an important contributor here. The researchers suspect lowered immunity in this population as being partly responsible for the development of the disease. The carcinoma is associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus, which is relatively common on human skin and multiple touched surfaces and shows no association with other diseases. The majority of those exposed do not develop Merkel cell carcinoma. People with weakened immune systems, on the other hand, may be more susceptible.

Older individuals already have inherently weaker immune systems than younger individuals (including a decline in B-cell and T-cell function). Added to this is the fact that in old age, other diseases such as autoimmune diseases are more frequently present or organ transplants have been performed, which require drug suppression of the patient’s own immune system.

However, this will not be the only explanation. Unprotected UV exposure is also a known risk factor, not only for Merkel cell carcinoma, but for all types of skin cancer. Possibly, the cumulative UV dose over time plays a particularly important role here. Apparently, Merkel cell polyomavirus undergoes mutation when exposed to UV, which in a large proportion of cases allows cancer to develop in the first place. In the remaining 20% or so of patients, the tumor is thought to arise directly from UV exposure without the intervention of the virus. As so often, the usual sun protection measures are therefore recommended: Stay in the shade, covering clothing, adequate waterproof sunscreen.

Finally, a caveat: Since awareness of the disease may also have increased in recent years, one cannot safely rule out the possibility that part of the increase in incidence was simply due to more frequent diagnoses/registrations.

Psoriasis – News on the blockade of interleukin 23

Interleukin blockade is one of the modern keys to psoriasis therapy. The list of targets and the drugs directed at them is growing. A human monoclonal antibody that selectively blocks the protein interleukin (IL) 23 is guselkumab. It was approved in the US and EU last year for moderate to severe plaque psoriasis.

At the congress, there was news about the long-term effect of the substance. Patients from the phase III trial called VOYAGE 2 were studied. 375 patients who were initially randomized to guselkumab and achieved a PASI90 response at week 28 were either re-randomized to placebo/therapy stop (with renewed guselkumab treatment if the PASI worsened accordingly) or continued guselkumab treatment until week 72 in a maintenance fashion.

Efficacy persisted until week 72 in the latter group (86% PASI90 response), and declined to 11.5% in the former during this period, as expected. Of the 182 patients in the therapy-stopped arm, 117 were retreated with guselkumab before week 72. 56 did not meet the criteria for retreatment, i.e., did not show “sufficiently” severe PASI worsening. They were not switched back to guselkumab until week 72.

Of the total 173 patients who were retreated with guselkumab after an interruption, 87.6% again achieved a PASI90 response within six months. There were new safety signals up to the 100. Week none. The long-term data are important for physicians to better assess guselkumab as a treatment option, the study authors said. VOYAGE 2 would have shown both that guselkumab maintained its efficacy over a 72-week period and that it could be reintroduced without major problems if therapy was stopped, with a rapid and robust response after six months.

And another representative…

That IL 23 blockade is a promising approach was also shown by data on the new active ingredient risankizumab. This was clearly superior to one of its approved “colleagues”, namely ustekinumab, in two phase III trials. At week 16, significantly more subjects achieved a PASI90 response and a score of 0 (“free of”) or 1 (“minimal”) on the Static Physician Global Assessment (sPGA) under the investigational agent than under ustekinumab.

- In the first study, it was 75.3%, and in the second, 74.8% with PASI90 response – compared with 42.0% and 47.5%, respectively, with ustekinumab.

- 87.8% and 83.7% achieved an sPGA of 0 or 1 in the respective study, this compared with 63.0% and 61.6%.

- The placebo values were, in the above order, after 16 weeks: 4.9%, 2.0%, and 7.8%, 5.1%.

- Response was still significantly higher than with unstekinumab at week 52 (after placebo patients had switched to risankizumab in part B of the study), while adverse event rates were comparable in the two drug groups. The most common side effect with risankizumab was upper respiratory tract infections.

Is the difference in efficacy due to the fact that risankizumab only blocks IL 23, and not additionally IL 12 like ustekinumab? Does tighter, possibly longer, binding to its molecular target cause the increased efficacy? Questions discussed at the congress. In addition, antibodies targeting IL 17, such as secukinumab (Cosentyx®), ixekizumab (Taltz®) and brodalumab, also appear to be more effective than ustekinumab. How would they fare against the new representative? At the time the studies were designed, these agents were not yet available for comparison, the study presenters noted. How exactly risankizumab will fit into the steadily growing psoriasis therapy market therefore remains to be seen for the time being.

Source: American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Annual Meeting, February 16-20, 2018, San Diego.

Literature:

- Paulson KG, et al: Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics. JAAD 2018; 78(3): 457-463.e2

- Heath M, et al: Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features. JAAD 2008; 58(3): 375-381.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(2): 36-39