Frostbite is thermal injury that occurs when tissue is exposed to low temperatures for a prolonged period of time. The resulting tissue damage can be so severe that amputation becomes necessary. Martina Schneider, MD, and Prof. Jan Plock, MD, report on how these thermal injuries are diagnosed and treated to avoid this ultima ratio if possible.

Frostbite is thermal injury that occurs when tissue is exposed to low temperatures for a prolonged period of time. In humid environments, even temperatures above freezing can cause tissue damage with prolonged exposure. The earliest records of frostbite or its treatment come from military reports, as these injuries were seen in rows among soldiers who were exposed to the elements during wartime. For example, Hannibal is said to have lost almost half of his army to frostbite during his crossing of the Alps. The first systematic report on frostbite was written by Baron Dominique Jean Larrey, Napoleon’s personal physician and chief surgeon of his Grande Armée, after the Russian campaign of 1812. At that time he propagated the slow warming up by massaging with ice or snow, because he had observed that many soldiers burned themselves additionally while trying to warm up their feet at the fire. It was not until after the Second World War that both Russian and German authors propagated rapid reheating [1].

Today, frostbite typically occurs in two groups. On the one hand, alpinists who expose themselves to extreme conditions and, on the other hand, homeless people who cannot find shelter from the weather or are at higher risk due to alcoholism.

Pathophysiology

Frostbite injuries occur through a direct and indirect mechanism. Direct cell damage comes from the formation of intracellular and extracellular ice crystals. In summary, this leads to cell dehydration, cell shrinkage, electrolyte shifts, denaturation of proteins and lipids, and even cell death [2,3].

Indirect cell damage results from microvascular changes such as formation of thrombi in capillaries, endothelial damage, increased release of mediators and free radicals. This in turn leads to impaired microcirculation and thus progressive tissue ischemia [2,3].

Clinic

Hands and feet are typical locations for frostbite. However, these can also occur on other acral regions such as the nose or ears. Symptoms are initially discrete. Often, the patient only notices numbness and some clumsiness in the fingers. The skin is usually only somewhat whitish, more rarely livid discolored, but may also be obviously frozen with formation of ice crystals.

However, the extent of the injury becomes visible only after rewarming. This is associated with severe pain for the patient. It is not until 12-24 hours after thawing that blistering occurs and the severity of the injury can be assessed. After another 1-2 weeks, the necrosis zone demarcates in deep frostbite.

Classification and prognosis

Classification: The traditional classification of frostbite is similar to that for burns:

- First degree: Redness and swelling due to hyperemia; no blistering, no tissue loss.

- Second-degree: Blistering with light-colored, serous contents; deeper dermis layers vital

- Third-degree: Hemorrhagic blisters, which progress to black necrosis; complete loss of dermis

- Fourth-degree: Also hemorrhagic blistering; additional necrosis of deep-seated structures such as tendons, muscles, or bones (Fig. 1).

Since this classification is not prognostically meaningful, there are also authors who make a more general classification into superficial (first- and second-degree) and deep (third- and fourth-degree) cold injuries [1]. Basically, it can be said that in the absence of blistering or blisters with clear fluid content, i.e. superficial frostbite, spontaneous healing without major scar development can be expected. In the case of deep frostbite, demarcation must be waited for. Thereafter, surgical debridement or amputation is often necessary.

Imaging

Technetium-99 scintigraphy can predict amputation level as early as the second to fourth posttraumatic day with a positive predictive value of 84% [4]. Magnetic resonance angiography can also provide information about tissue perfusion and thus amputation level at an early stage [5]. Since, as a rule, demarcation is always awaited before amputation, imaging is purely prognostic and has no influence on therapy.

Therapy

Rewarming: As soon as frostbite is detected, rapid rewarming should be attempted. It must be taken into account that freeze-thaw-freeze leaves greater damage than delayed heating. For this reason, it should be ensured that heating is continuous. Likewise, an extremity with frostbite should no longer be loaded. If this is unavoidable, e.g., if recovery is not possible, it is recommended that the limb not be warmed until it has reached a safe location [6]. Frozen fingers or toes should not be warmed with heating pads or by rubbing, as this carries the risk of additional tissue damage from burning or mechanical damage. Heating is best done in 37°-39° C warm water [7] with the addition of povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine if necessary. Heating takes place until a reddish color appears and the tissue is soft and mobile.

Analgesia: Warming up in particular can be very painful, which is why sufficient analgesia, often with opiates, is necessary.

Due to the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effects, the administration of an NSAID is recommended. The most commonly mentioned is ibuprofen, which is administered at a starting dose of 12 mg/kg every 12 h and can be increased to a maximum of 2400 mg/24 h depending on analgesic need [6]. Alternatively, aspirin may be given. However, it is not the first choice due to the inhibition of prostaglandin action, which is beneficial for wound healing [2].

If amputation becomes foreseeable in the course, it is useful to evaluate neuroleptics such as gabapentin, pregabalin, or amitriptyline early on to prevent chronification of neuropathic pain.

Local therapy: After warming up, the body part is dried in the air, also to avoid shearing forces. Blister ablation, especially of hemorrhagic blisters, has long been controversial. In the more current literature, authors increasingly agree that all blisters should be ablated [2,6] with application of a sterile protective dressing.

For superficial injuries, an absorbent wound dressing, e.g. Mepithel®, can be used and left in place for several days. These wounds heal under conservative therapy. In the case of deep-seated injuries, there is an increased risk of wound infection, which is why regular dressing changes are essential. The affected limb should be positioned above heart level and immobilized by means of a splint.

Antibiotic therapy/tetanus: There is no evidence for prophylactic antibiotic therapy. If there are clinical symptoms of wound infection, it is indicated after taking wound swabs.

Frostbite is not associated with tetanus infection, but a tetanus booster is recommended.

Thrombolytic therapy/Iloprost: To reduce progressive tissue ischemia due to microvascular changes, especially the formation of microthrombi, thrombolytic therapy with tissue-type plasminogen activator (“t-PA”) can be performed. Bruen et al. were able to show that this therapy significantly reduces the amputation rate when started in the first 24 h after trauma [8]. Administration of t-PA is intra-arterial in combination with heparin under close circulatory monitoring [9]. Indications are fresh deep frostbite. Thrombolytic therapy is contraindicated in the presence of a history of a freeze-thaw-freeze cycle as well as increased risk of bleeding or concomitant neurologic symptoms.

A good alternative to systemic thrombolysis is therapy with iloprost (Ilomedin®), a synthetic prostacyclin derivative. It causes platelet aggregation inhibition, peripheral vasodilation, increase of capillary density, reduction of capillary permeability and stimulates endogenous fibrinolytic potential. Via this effect, it also reduces progressive tissue ischemia. Cauchy et al. were able to demonstrate a significant reduction in the amputation rate compared with therapy with buflomedil (α-adrenoceptor antagonist). Likewise, therapy with iloprost alone was superior to the combination of iloprost with t-PA [10].

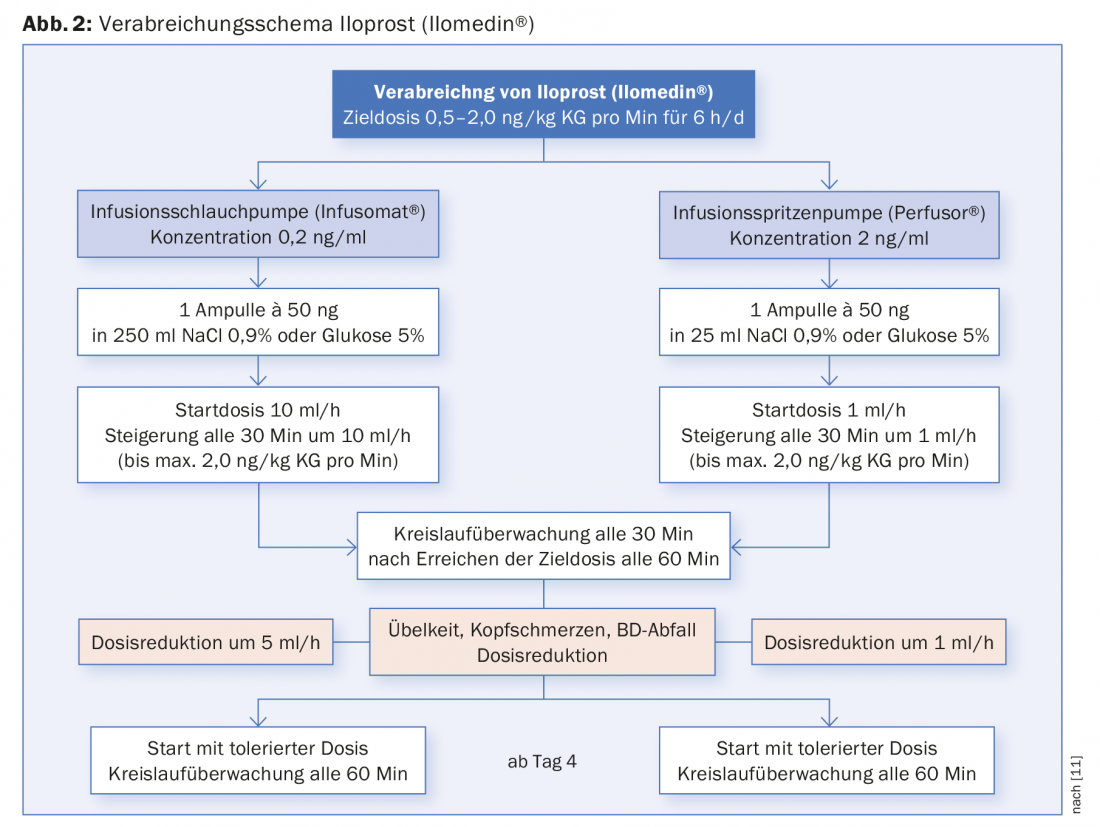

Compared with systemic lysis, iloprost has the advantage that it can be administered via peripheral venous access and is not contraindicated in concomitant injuries. However, unstable angina, myocardial infarction within the last six months, relevant cardiac arrhythmias and heart failure are contraindications. Administration is for 6 h per day, with tolerated doses determined in the first 2-3 days. Regular circulation monitoring is performed during administration (Fig. 2).

Surgical therapy: The saying “Frozen in January – amputate in July” is still valid. In case of frostbite of the acras, autoamputation should be waited for in terms of demarcation. This may take several weeks to months in some circumstances. Only in rare cases such as wet gangrene, colliquative necrosis, or extensive wound infection with concomitant sepsis is prompt surgical debridement indicated. In these cases, it is recommended to perform an imaging workup using 99Tc scintigraphy or MR angiography to avoid too extensive amputation [2].

Complications and long-term consequences

Functional limitation depends on the extent of the injury. The goal is early, interdisciplinary care by physicians, nurses, occupational therapists, physical therapists and, if needed, orthotists and psychologists. Follow-up procedures may be necessary for unstable scars, scar contractures, or post-traumatic osteoarthritis. Chronic pain remains a challenge, which can lead to significant impairment in addition to functional deficit.

Take-Home Messages

- As soon as frostbite is detected, rapid rewarming in a 37-39°C water bath should be attempted.

- Avoid freeze-warm-freeze

- Since rewarming can be very painful, sufficient analgesia is necessary. Due to the anti-inflammatory and analgesic effect, the administration of an NSAID is recommended (e.g. ibuprofen).

- Evaluation of thrombolytic therapy with iloprost in profound frostbite.

- Evaluation of neuroleptics for the prevention of chronic pain.

- Waiting for definitive dry demarcation before possible amputation

Literature:

- Cochran A, Morris SE, Saffle JR: Cold-induced injury: frostbite. Herndon DN (ed) Total Burn Care. Fifth Edition 2018; Elsevier Publishing.

- Handford C, Thomas O, Imray CHE: Frostbite. Emerg Med Clin North Am 2017; 35(2): 281-299.

- Murphy JV, et al: Frostbite: pathogenesis and treatment. J Trauma 2000; 48(1): 171-178.

- Cauchy E, et al: The value of technetium 99 scintigraphy in the prognosis of amputation in severe frostbite injuries of the extremities: A retrospective study of 92 severe frostbite injuries. J Hand Surg Am 2000; 25(5): 969-978.

- Barker JR, et al: Magnetic resonance imaging of severe frostbite injuries. Ann Plast Surg 1997; 38 (3): 275-279.

- McIntosh SE, et al: Wilderness Medical Society practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of frostbite: 2014 update. Wilderness Environ Med 2014; 25(4): 43-54.

- Malhotra MS, Mathew L: Effect of rewarming at various water bath temperatures in experimental frostbite. Aviat Space Environ Med 1978; 49(7): 874-876.

- Bruen KJ, et al: Reduction of the incidence of amputation in frostbite injury with thrombolytic therapy. Arch Surg 2007; 142(6): 546-551.

- Handford C, et al: Frostbite: a practical approach to hospital management. Extreme Physiol Med 2014; 3: 7.

- Cauchy E, Cheguillaume B, Chetaille E: A controlled trial of a prostacyclin and rt-PA in the treatment of severe frostbite. N Engl J Med 2011; 364(2): 189-190.

DERMATOLOGIE PRAXIS 2018; 28(3): 14-17