Cholecystocolic fistulas (CCF) are the second most common form of cholecystoenteric fistula (CEF). CCFs can occur atypically and result in high morbidity and mortality if not diagnosed immediately. American physicians presented a case of CCF and obstructing gallstone in an elderly man who lacked many of the expected signs, symptoms and risk factors.

A cholecystoenteric fistula (CEF) is a spontaneous duct that forms between an inflamed gallbladder and one or more parts of the surrounding gastrointestinal tract. It is often due to long-standing cholelithiasis. Cholecystocolonic fistulas (CCF) are the second most common type of CEF after cholecystoduodenal fistulas. Although rare overall, cholecystocolonic fistulas should be considered in the differential diagnosis of elderly individuals with intestinal obstruction symptoms.

A 75-year-old man with a history of gallstones, gastroesophageal reflux disease, congestive heart failure, atrial fibrillation, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and a five-day history of constipation and loss of appetite presented to Dr. James S. Barnett’s team at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston [1]. He reported no abdominal pain, fever, weight loss, nausea or vomiting, and no prior gastrointestinal surgery or endoscopy.

His abdomen was soft and non-tender with normal bowel sounds without thickening or organomegaly. Vital signs were normal except for mild hypertension. Laboratory testing revealed a slightly elevated aspartate aminotransferase (0.82 µkat/l), normal alanine aminotransferase (0.45 µkat/l), slightly elevated alkaline phosphatase (1.82 µkat/l), normal total bilirubin (18.81 µmol/l) and a normal complete blood count.

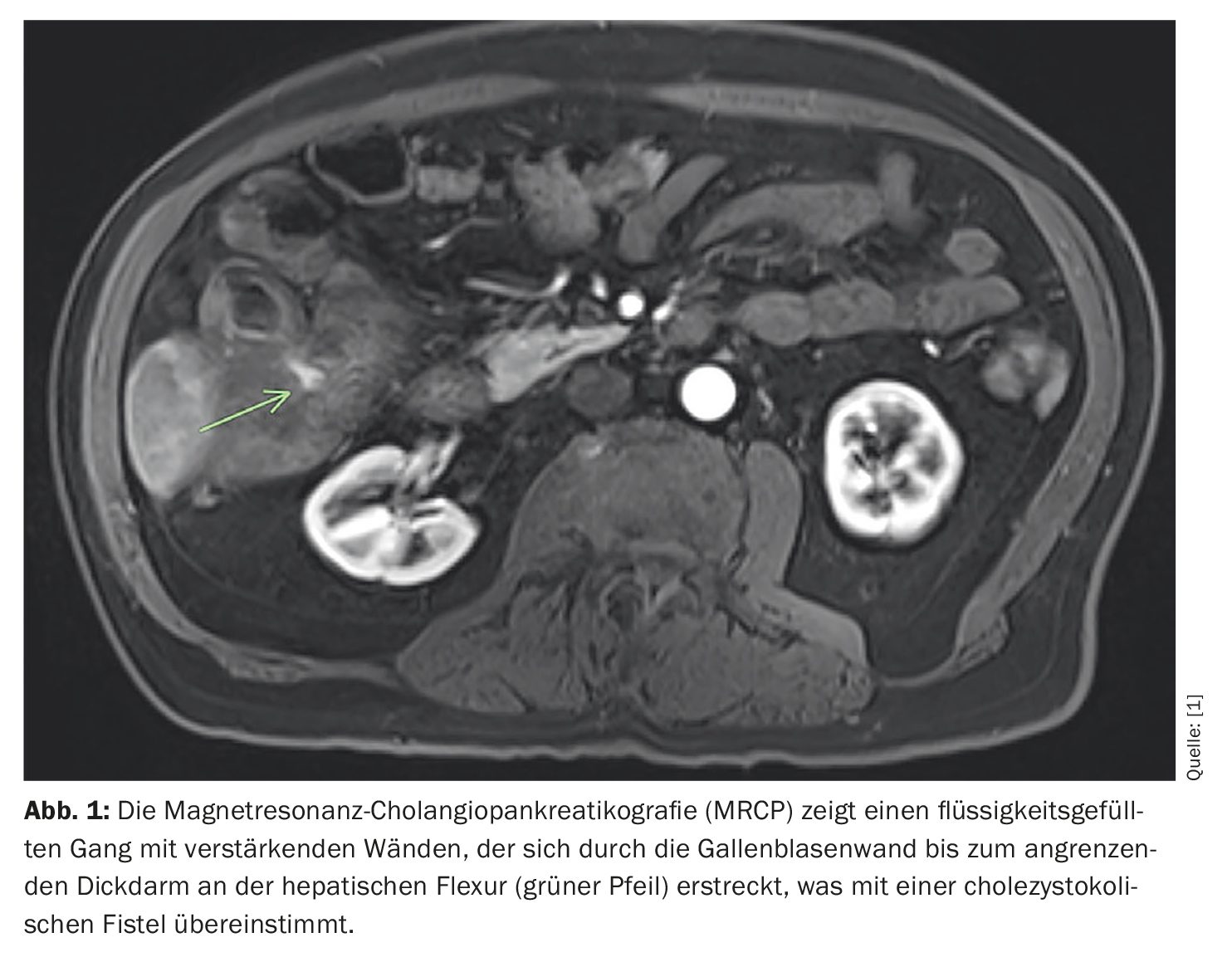

CCF was diagnosed by MRCP and an obstructing gallstone

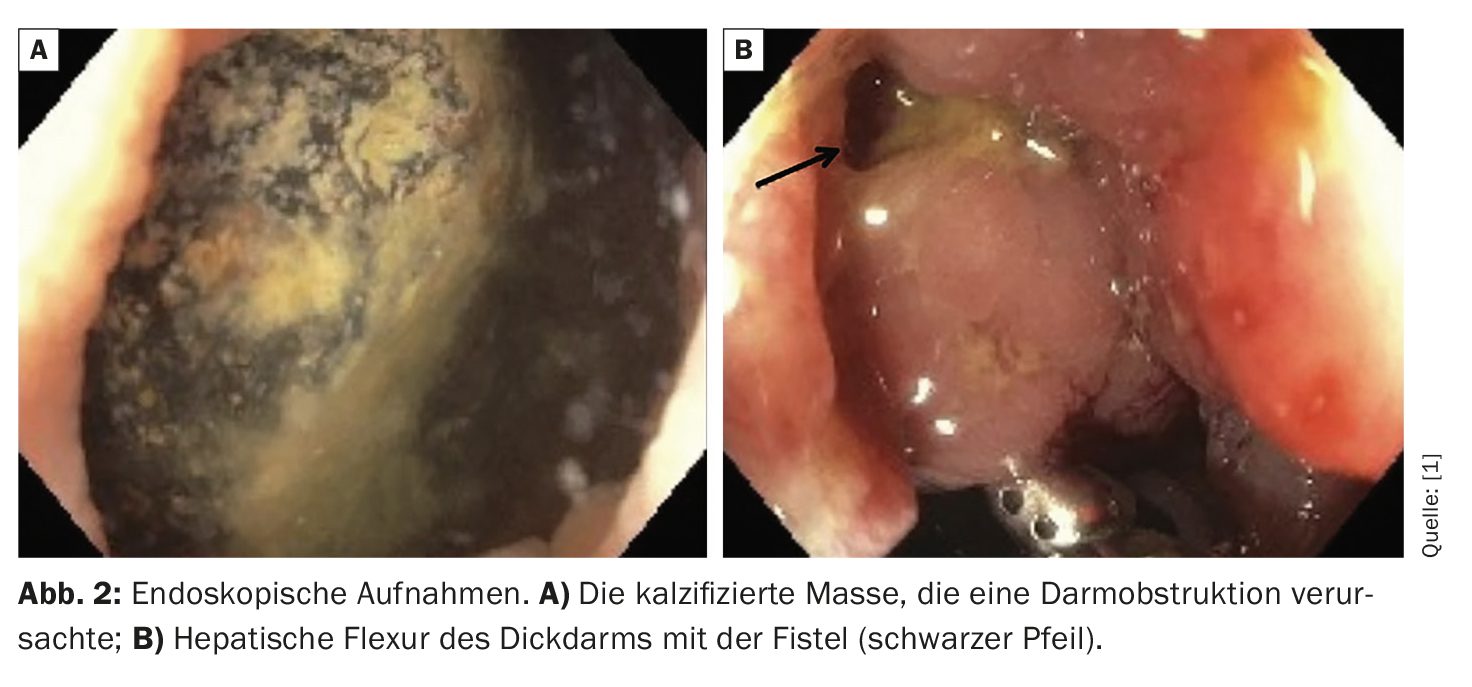

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast showed an enhanced and thickened gallbladder wall, pericholecystic fluid, intra- and extrahepatic pneumobilia, and a 4.2 cm × 3.7 cm × 5.8 cm mass in the sigmoid colon with no evidence of bowel dilatation. In contrast, a CT scan performed 12 years earlier showed a 3 cm peripherally calcified stone in the gallbladder that resembled the newly found calcified mass in the sigmoid colon, with no evidence of the current colonic mass on previous images. The patient then underwent magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP), which showed a fistulous connection between the gallbladder and the adjacent colon at the hepatic flexure (Fig. 1). This was followed by colonoscopy, which revealed the obstructing mass in the sigmoid colon (Fig. 2).

The doctors tried several times to crush the mass mechanically with 26 mm and 33 mm slings and a rattan forceps, but without success, as the mass was too hard and the salvage of the mass with a salvage basket was not successful. As lithotripsy was not available at the facility where the patient was hospitalized and no other endoscopic procedures could be performed, the mass was surgically removed manually under anesthesia. After removal of the mass, the patient underwent a repeat colonoscopy, during which a fistula was found endoscopically (Fig. 2). In addition, granular tissue was found causing a narrowing at the same site as the fistula. This was biopsied and found to be negative for dysplasia but showed focal active inflammation. The pathology of the mass confirmed it as a gallstone, Dr. Barnett and colleagues explain.

The patient’s bowel function was restored and he was discharged with the plan to possibly have the fistula removed in the future. The patient was later examined by a surgeon at the clinic to address the fistula removal. A repeat CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis was requested to plan the surgical procedure, which according to the doctors has not been completed to date.

Serious complications possible

Cholecystoenteric fistula is a sequela of chronic cholecystitis and occurs in 0.5% to 0.9% of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cholecystocolic fistulas account for 8% to 26.5% of all CEFs. Repeated episodes of cholecystitis or a prolonged history of cholelithiasis, especially over a period of more than 5 years, may be a risk factor for the development of CEF, the authors write. Small bowel obstruction due to gallstone ileus is a common complication of CEF and the cause of up to 25% of non-strangulated small bowel obstructions in patients over 65 years of age.

The most common symptoms of CEF include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, none of which were present in this patient, Dr. Barnett and colleagues emphasized. In this case, the patient presented with new-onset constipation without the expected symptoms of gallstone ileus. The diagnosis here relied on imaging to reveal the pneumobilia, CCF and obstructing gallstone in the colon. A review of previous imaging was also helpful as the affected gallstone in the sigmoid had been identified 12 years earlier in the gallbladder. The patient had been asymptomatic until his presentation with subacute intestinal obstruction. It is crucial to recognize CCF and its complications promptly, as the consequences of undiagnosed CCF can be life-threatening, including intestinal obstruction, intestinal necrosis, perforation, cholangitis, sepsis, liver abscess and massive hemorrhage, the authors concluded. In older patients with a history of gallstones and new constipation, it is therefore important to include CCF in the differential diagnosis.

Literature:

- Barnett JS, et al: An Unusual Presentation of Cholecystocolonic Fistula and Subacute Colonic Obstruction. AIM Clinical Cases 2024; 3: e240249; doi: 10.7326/aimcc.2024.0249.

GASTROENTEROLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 2(2): 20-21