The most common form of dementia is Alzheimer’s dementia, which is chronically progressive and primarily shows memory impairment. After initial exclusion diagnosis by the primary care provider, differential diagnosis should be performed at a referral clinic. This enables the differential diagnosis of dementia diseases.

Clinically, according to DSM IV-TR and ICD-10, the diagnosis of dementia is currently based on evidence of memory impairment as well as disturbances in reasoning, attention, and other disorders such as aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or impairment of executive functions. Additional deterioration from previous levels of performance and impairment of daily living skills must be identified.

Causes of dementia

At the end of 2012, the number of people over 60 years of age in Switzerland was 1.8 million, which, with a dementia prevalence of 6.9% in Western Europe [1], suggests that there are over 120,000 dementia patients in this group. The most common causes of dementia are Alzheimer’s disease (AD), vascular forms of dementia (VaD), and dementia associated with Parkinson’s/Lewy body dementia (PDD/DLB). In the under-60s, fronto-temporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) and cognitive impairment due to psychiatric disorders, such as alcohol abuse, play an important role [2]. In old age, mixed forms of AD and vascular pathology are the most common cause [3]. The potentially reversible causes of dementia are in the clear minority.

Differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s dementia

Exclusion diagnostics continue to be of central importance. In the primary diagnosis, the detailed anamnesis is central, which should also record the effects of the cognitive disorders on the patient’s everyday life and social situation. Current stress factors and indications of a depressive syndrome should be specifically inquired about. The use of a screening instrument (e.g. MMSE with clock test) is useful and helpful. The following tests are routinely recommended: CBC, Na, K, Ca, creatinine, urea, GPT, GOT, gamma-GT, albumin, fasting glucose and HBA1c, TSH, BSR, CRP, vitamin B12 and folic acid, and cerebral imaging [modifiziert nach 4].

In any dementia syndrome, referral to a memory clinic should be considered, always taking into account the will of patients and relatives and reservations, fears and expectations of all involved.

Sporadic AD is the most common cause of dementia and begins slowly progressive with memory impairment without neurological deficits. Apart from affective symptoms such as anxiety and depression, which may occur at the beginning or even before the disease, the personality remains intact for a long time. Deviations from this typical picture, such as an early onset, rapid progression, onset with behavioral or speech disorders, and fluctuating course of cognitive symptoms, may be indicators of a different form of dementia and suggest that the patient should be presented to a memory clinic. The occurrence of focal neurologic symptoms and quantitative disturbances of consciousness requires immediate evaluation.

The following basic knowledge regarding the most common differential diagnoses of AD is highly relevant:

1. fronto-temporal lobar degenerations (FTLD) are a clinically and pathologically heterogeneous group. New proteins contributing to neurodegeneration (TDP-43, FUS) have been identified in recent years. The hallmark of fronto-temporal lobar degeneration is atrophy of the frontal and temporal lobes, the pattern of which determines the variable clinical picture.The best known is the division into fronto-temporal dementia (FTD) with primary behavioral disturbances and progressive non-fluent aphasia (PA) and semantic dementia (SD) with primary language disturbances [5].

Core symptoms of fronto-temporal dementia are a change in personality and social behavior, early emotional blunting, and loss of disease insight.Memory is relatively intact at the onset of the disease.

In non-fluent aphasia, which is often also based on AD pathology, the flow of speech is disturbed. Typical are disturbances of word finding and grammar as well as word wording. In the course, an increasing

Develop mutism. Although patients appear severely impaired as a result, cognitive performance outside of speech is often maintained for a long time. The language of semantic dementia is fluent, but often empty of content. The meaning of objects or even familiar faces are no longer recognized. Information is often no longer understood.

2. in Lewy body dementia and Parkinson’s dementia, deposits of α-synuclein are the characteristic feature. Memory impairment is not a diagnostic requirement. Parkinson’s dementia is diagnosed in the context of prolonged Parkinson’s disease when a cognitive impairment that impairs social or occupational performance levels develops. In DLB, cognitive dysfunction becomes apparent prior to Parkinson’s disease symptoms or close to them, and AD pathology usually accompanies it. Core symptoms are a severe fluctuation of cognitive performance with fluctuating wakefulness and attention, also recurrent detailed visual hallucinations and parkinsonian symptoms. Also indicative is REM sleep behavior disorder and severe sensitivity to dopamine antagonists, the administration of which should be avoided at all costs if DLB/PDD is suspected. If two core symptoms or one core symptom and one suggestive symptom are present, one can diagnose probable PDD/DLB.

3. vascular dementias are clinically and pathologically very heterogeneous. For example, multi-infarct dementia is distinctly different from subcortical arteriosclerotic encephalopathy (SAE). While small strategic infarcts are sufficient to cause a dementia syndrome, larger infarcts may be clinically silent. Imaging to detect an explanatory vascular lesion is central, and ideally there is a temporal relationship between the appearance of the lesion and the cognitive impairment [6], which is particularly difficult in SAE. In the frequent mixed forms with AD, it is difficult in individual cases to determine the share of the respective pathology in the disorder.

Alzheimer’s dementia and depression – similarities and differences

The prevalence of major depression in the elderly is 3%. In addition, 40% show clinically relevant depression symptoms [7]. Depression in old age often accompanies neurodegenerative diseases. It is not uncommon for older individuals with an onset of cognitive impairment to see their doctor because of depressive symptoms. Conversely, geriatric depression can cause significant cognitive impairment. Examples include general decline in information processing and impairment in episodic memory, language, and executive functions [8]. Moreover, there may be a common neurobiological basis of old-age depression and AD [9]. There is evidence of chronic inflammatory processes, excessive activation of the HPA axis, and disruption in the nerve growth factor signaling cascade. This may be one reason for the higher risk of AD in recurrent depressive disorder.

In AD, the focus is on disturbances in orientation in addition to memory disturbances, whereas the latter is usually intact in depression. Depressed patients often have a history of depression, and the cognitive disorder regresses with treatment. Neuropsychology can also detect differences: in AD, compared to depression, recognition is significantly impaired – intrusions and constructive-apractical errors occur [10]. Due to the better prognosis of the cognitive disorders of depression with treatment, early diagnosis of the disease in the elderly is urgent. Antidepressant treatment is also indicated for depressive symptoms associated with AD.

Dementia versus delirium

The clinical symptoms of AD and delirium often overlap, making differentiation difficult. Both disorders show memory, orientation and language disorders and have accompanying symptoms such as depression, sleep-wake rhythm disturbances, agitation and aggression [11]. Only the disturbance of consciousness is characteristic for delirium and does not occur in AD. However, this symptom can only be detected by continuous observation because it fluctuates strongly. Delirium as an acute condition can be reversed by treatment of the trigger. In contrast, the cognitive disturbances of AD worsen over a longer period of time. Because age and AD are risk factors for delirium, the two conditions often occur together. In cases of V.a. delirium, a comprehensive search for causative factors such as infections, metabolic disorders, and medications is indicated. Delir scales help in the differential diagnosis.

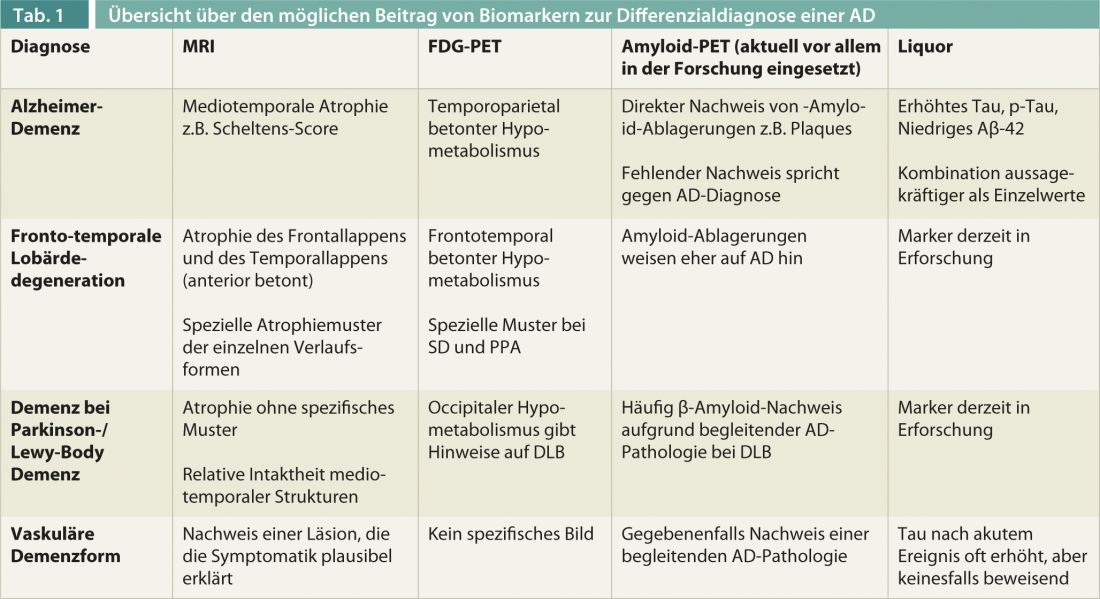

Outlook: Direct detection of pathology by biomarkers.

The specificity of a clinical AD diagnosis for pathologic confirmation is currently a median of 58, and the sensitivity is 87% [12]. Biomarkers are increasingly being used to improve diagnostic accuracy, which will be particularly important in the use of specific therapies such as immunotherapy against β-amyloid and early diagnosis (Table 1).

PD Egemen Savaskan, M.D.

Anton Gietl, MD

Literature:

- Alzheimers Dement 2013; 9(1): 63-75 e2.

- Lancet Neurol 2010; 9(8): 793-806.

- Acta Neuropathol 2010; 119(4): 421-433.

- DGPPN: Diagnosis and Treatment Guideline Dementia. 2010.

- Neurology 1998; 51(6): 1546-1554.

- Neurology 1993; 43(2): 250-260.

- Savaskan E: Depression in the elderly: what the primary care physician should know. InFo N&P 2011; 9 (5-6): 21-24.

- Am J Psychiatry 2012; 169: 1185-1193.

- Eur J Pharmacol 2010; 626: 64-71.

- Beblo T, Lautenbacher S: Neuropsychology of depression. Hogrefe Publishers, 2006.

- Leading Opinions, Neurology & Psychiatry 2012; 1: 6-7.

- J Neuropathol Exp Neutrol 2012; 71: 266-273.