There was big news at the 2017 ASCO Congress. First, abiraterone is pushing into the first-line setting in metastatic prostate cancer. On the other hand, there is a new standard in adjuvant therapy of tumors of the biliary system. The data are now expected to change clinical practice “overnight,” so to speak.

Patients with a new diagnosis of metastatic prostate cancer have a poor prognosis. This is even more true if they also have high-risk characteristics. On average, they die of their disease after less than five years. Approaches to improve survival in this group without losing sight of the toxicities of intensive therapy have now received a significant boost with the two trials presented at ASCO 2017 called LATITUDE and STAMPEDE.

This much in advance: Instead of being used after castration resistance , abiraterone is used concomitantly with hormone therapy (ADT) from the beginning, i.e. in the first line, which in the studies led to a benefit (at least) comparable to that under docetaxel chemotherapy. Compared to the latter, however, abiraterone is tolerated much better, with many patients showing no side effects at all. Thus, significantly more people should be eligible for this therapy. Experts at the congress already spoke of “results that will change practice overnight.” Is that really the case?

Background

Testosterone drives the growth of a prostate carcinoma: Testosterone accumulates at special binding sites of the prostate cells, the androgen receptors, which subsequently leads to cell division and cell growth – in prostate carcinoma cells, this mechanism is disturbed, resulting in uncontrolled growth. Hormone therapy, in turn, suppresses the formation of androgens or inhibits their effect on tumor cells.

In so-called androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), hormone production in the testes is suppressed. However, small amounts of androgens continue to be produced e.g. by adrenal cortex. Abiraterone interferes with hormone regulation by blocking an enzyme that converts other hormones into testosterone in several steps (endogenous androgen biosynthesis). This inhibition stops the production of testosterone not only in the testes, but also in the adrenal glands and prostate, or in the tumor tissue itself. It is currently approved:

- for treatment in combination with LHRH agonists and prednisone or prednisolone in patients with advanced metastatic prostate cancer at progression after treatment with docetaxel.

- for treatment in combination with LHRH agonists and prednisone or prednisolone in asymptomatic or mildly symptomatic patients with metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer without visceral metastases and without liver metastases, after failure of androgen receptor blockade, when chemotherapy is not clinically indicated.

LATITUDE – blinding removed at an early stage

Randomized were approximately 1200 patients with metastatic, hormone-naïve, high-risk prostate cancer diagnosed three months or less before randomization. ECOG performance status was 0-2.

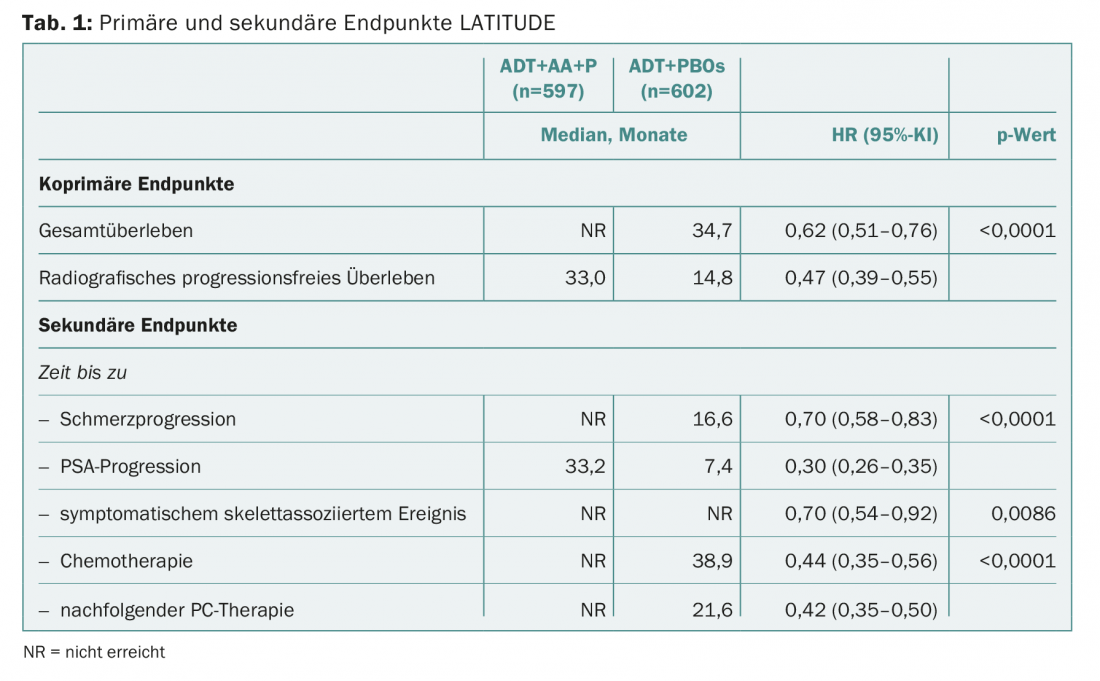

The Phase III trial was unblinded early based on compelling results from an initial interim analysis. Placebo patients were included in the study group. At this point, a median of 30 months had passed. In both coprimary and all secondary endpoints, the combination of abiraterone (1 g/d) plus prednisone (5 mg/d) and ADT significantly superior to ADT alone (plus placebo). (Tab.1). Median overall survival in the abiraterone group could not yet be calculated (“has not yet been reached”) because more than half of the patients in this group were still alive when the analysis was performed.

With a 38% reduction in the risk of death and a more than 50% reduction in the risk of progression, the question now naturally arises as to whether abiraterone in the first-line setting can convince not only in terms of efficacy but also in terms of safety. Overall, the risk-benefit profile clearly favored the agent and thus early abiraterone use in this patient population. The authors cited hypertension (20.3% vs. 10%) and hypokalemia (10.4% vs. 1.3%), which are typical and well-known with abiraterone, and increased transaminases as grade 3/4 adverse events that occurred more frequently compared with placebo. So, according to the study authors, caution is advised in patients at increased risk for heart problems, such as those with diabetes or CHD.

STAMPEDE – Confirmation of the results

After decades of treating metastatic prostate cancer with hormonal approaches, evidence of a survival benefit with the addition of docetaxel chemotherapy was published in 2015 with the CHAARTED trial [1]. Now, in 2017, the same is true for abiraterone (but with significantly fewer side effects). In the following it would still have to be clarified whether abiraterone in addition to chemotherapy can further increase the benefit.

The so-called STAMPEDE trial with Swiss participation does not provide a direct answer to this question. Rather, the aim is to show again, summarized in an innovative study design, how the two approaches compare with ADT alone and whether, if so, one variant is superior in terms of efficacy. Now, the ASCO Congress would not be the largest and most important international oncology meeting if it did not also have to offer initial results from this study. STAMPEDE investigates a total of six therapeutic strategies, alone or in combination and always in addition to hormone therapy. Docetaxel and abiraterone are included but are only indirectly compared, not combined.

The data presented confirmed the positive signals from LATITUDE: again ADT alone and with immediate addition of abiraterone were compared. ADT for at least two years plus mandatory radiotherapy for N0M0 disease and recommended radiotherapy for N+M0 disease was considered the “standard of care.” The sample consisted of patients with locally advanced or metastatic high-risk prostate cancer. The latter was true for 52% of the carcinomas, and 95% were considered newly diagnosed. A total of 1917 subjects were randomized. Consequently, this was the largest study of abiraterone in the first-line setting and in this indication.

When abiraterone and prednisolone were added at the same dosage as in LATITUDE, survival also prolonged. After a median of 40 months, the risk of death was significantly reduced by a similar 37% (HR 0.63; 95% CI 0.52-0.76). After three years, 83% vs. 76% of patients were alive. The risk of treatment failure was reduced by a full 71% with the addition of abiraterone (HR 0.29; 95% CI 0.25-0.34) – the difference was significant. Failure this time was also considered to be a worsening in symptoms or PSA level. The effects behaved consistently across different subgroups (including metastasis/no metastasis, nodal status, etc.).

The side effect profile was again judged to be tolerable and controllable. When the total number of adverse events was considered, the two groups were comparable. Grade 3 adverse events, on the other hand, were found in 41% vs. 29% and grade 4 in 5% vs. 3%. Grade 5 events occurred in 9 vs. 3 subjects, and were related to treatment in two vs. one case each. With abiraterone, cardiovascular problems such as hypertension and aminotransferase elevations were again more common.

The authors of STAMPEDE concluded from their results that ADT (+/- radiotherapy) and abiraterone were a new standard of care for this population.

Found a new standard?

If various voices at the congress – including lead study author Nicholas James and ASCO congress medical officer Richard Schilsky – are anything to go by, abiraterone is now clearly being pushed into the first-line setting. Both the survival of 83% vs. 76% and the rate of patients without treatment failure of 75% vs. 45% at three years are extremely encouraging and impressive results from STAMPEDE, James said. The fact that the risk of symptomatic skeletal events was reduced by more than half after three years under abiraterone added to the positive balance of the active substance. All the above advantages are shared by the LATITUDE data.

The primary target population for the new standard would be men with high-risk prostate cancer that is newly diagnosed and in the locally advanced or metastatic stage.

Some voices warned against jumping to conclusions. In any case, it is a double-edged sword. Cardiovascular risks, he said, should be carefully considered in patient selection-part of the improvement in cancer mortality may be due to deaths shifting toward heart disease (i.e., fewer patients die of cancer overall because some succumb earlier to heart problems).

Both studies were published concurrently with the congress in the New England Journal of Medicine [2,3].

Tumors of the biliary system – breakthroughs here as well

Tumors of the biliary system, although rare, are unfortunately associated with poor outcome. Only just one-fifth of patients are suitable for a curative approach, namely surgical resection, at the time of diagnosis. Even then, the 5-year survival is still below 10%. For the first time, a sufficiently large study has now shown a clear survival benefit of adjuvant concomitant therapy, namely with capecitabine.

The phase III trial, called BILCAP, compared wait-and-see observational behavior after radical surgery with capecitabine 1250 mg/m2 on days 1-14 every 21 days for eight cycles. At the time the study was planned and initiated, observation was the standard procedure after resection. The researchers chose capecitabine because it can be administered as a tablet and had shown efficacy in pancreatic cancer (a disease with a similar poor prognosis). Participants were 447 patients from the United Kingdom with completely resected cholangiocarcinoma or gallbladder cancer with adequate biliary drainage/renal, hematologic, and liver function, no existing infection, and an ECOG performance status of highest 2 (majority 0 and 1). Resection margins were two-thirds R0, and just over one-third R1. Approximately half were lymph node negative.

Median overall survival was 51 months with adjuvant therapy and 36 months without. The result missed statistical significance (p=0.097). However, some patients had stopped the study drug early. Considering the still large group of 430 patients who took capecitabine for six months as per protocol, the difference reaches significance: patients lived 53 months with adjuvant therapy and only 36 months without (significant risk reduction of 25%, p=0.028).

The effect of the drug was so clear that the missed significance in the overall population did not call its efficacy into question, the study authors said. In addition, the risk-benefit balance clearly tilted toward the benefit side, as the toxicity of the therapy was lower than expected. There were no treatment-associated deaths; the most common was the rash on the hands and feet known to occur with capecitabine. The unmistakable conclusion of the researchers is that a new standard of adjuvant therapy for biliary tumors has been found. Especially since capecitabine is widely available and used, so doctors already have a lot of experience with the drug.

There are not many phase III trials in adjuvant chemotherapy in this setting. BILCAP is one of the largest and thus has a relevance to clinical practice that should not be underestimated. Another study of gemcitabine and cisplatin is underway, but its results are not expected for a few years. Until then, capecitabine is clearly preferable, the authors said. What remains to be determined is which subtumors of the biliary system benefit most. Appropriate subgroup analyses from BILCAP are underway for this purpose, as tumor locations were relatively evenly distributed in the main study. Previous studies suggest a difference depending on the type of tumor.

Source: American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) 2017; Annual Meeting, June 2-6, 2017, Chicago.

Literature:

- Sweeney CJ, et al: Chemohormonal Therapy in Metastatic Hormone-Sensitive Prostate Cancer. NEJM 2015; 373: 737-746.

- James ND, et al: Abiraterone for Prostate Cancer Not Previously Treated with Hormone Therapy. NEJM 2017. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1702900 [Epub ahead of print].

- Fizazi K, et al: Abiraterone plus prednisone in metastatic, castration-sensitive prostate cancer. NEJM 2017. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMoa1704174 [Epub ahead of print].

InFo ONCOLOGY & HEMATOLOGY 2017; 5(4): 37-40.