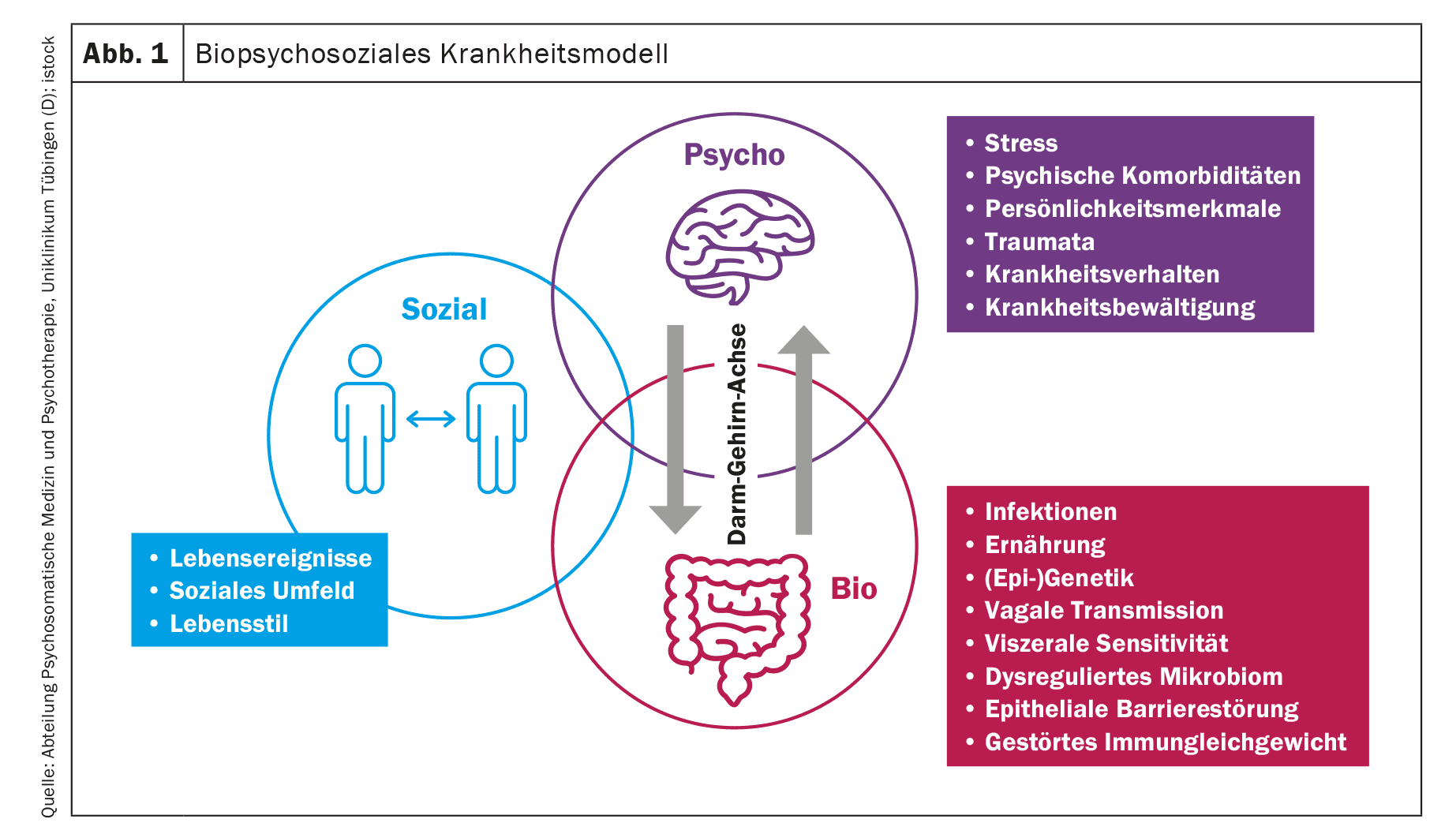

The biopsychosocial model considers various somatic and psychosocial factors within the pathophysiology of IBS and integrates their multifaceted interaction processes. In addition, therapeutic starting points can be identified and implemented on a biological, psychological and social level.

You can take the CME test in our learning platform after recommended review of the materials. Please click on the following button:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a somatoform/functional disorder of the lower digestive system [1] with an estimated worldwide prevalence of approx. 11% [2] and an estimated incidence of approx. 1.5% [3], with the disorder occurring more frequently in women than in men [4]. With a prevalence of 5-10% in Germany [2], IBS is one of the most common gastrointestinal dysfunctions [5]. In this context, IBS leads to a considerable impairment of the quality of life of those affected [6] and also causes large direct costs (e.g., due to visits to the doctor, medication, diagnostics, hospitalization, etc.) as well as indirect costs (especially due to absences from work and reduced productivity during work) [7]. The present review article takes the revised S3 guideline for IBS published in Germany in 2021 [7] as an opportunity to present current recommendations for action regarding the diagnosis and therapy of IBS. This guideline was developed in cooperation with the relevant specialist societies in Germany, but also with the involvement of the Swiss Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility, and is also valid in Switzerland.

According to the updated guideline [7], IBS is present when the following three criteria are met:

- chronic, i.e. lasting longer than three months, or recurrent, bowel-related complaints (e.g. abdominal pain, flatulence), usually accompanied by changes in bowel movements;

- the symptoms lead the person concerned to seek help and/or worry about them and the symptoms are so severe that the quality of life is significantly impaired;

- that there are no changes characteristic of other clinical pictures that are responsible for the present symptoms.

In terms of prognosis, the symptoms of IBS spontaneously resolve in some patients, but often progress chronically, whereby IBS does not appear to be associated with the development of other gastrointestinal or other serious diseases and does not have an increased mortality rate [8]. However, a high comorbidity with mental disorders has been shown [9]. Due to the lack of curative options, the treatment of IBS is mainly aimed at alleviating the symptoms [10]. Therapeutic measures in this regard against the background of the biopsychosocial model are the subject of this article.

Note: Irritable bowel syndrome is a somatoform/functional disorder of the lower digestive system that is associated with persistent, i.e. lasting longer than three months or recurring, bowel-related symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating and changes in bowel movements and significantly impairs the quality of life of those affected.

| Abbreviations |

| DIGAs = digital health applications FODMAPs = fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols GDH = gut-directed hypnotherapy HPA axis = hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis RCT = randomized controlled trial RDS = irritable bowel syndrome RDS-D = Diarrhea-predominant IBS RDS-O = Obstipation-predominant IBS SNRI = Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor SSRI = Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor |

Pathogenesis

Based on a biopsychosocial model, it can be assumed that various somatic (e.g. [Epi-]genetics, infections), psychological (e.g. chronic stress, illness behavior) and social aspects (e.g. socioeconomic status) are involved in the pathophysiology of IBS (Fig. 1) [11]. Thus, numerous biological alterations have since been identified that are associated with IBS symptomatology [1,10]. The most frequently investigated abnormalities include motility disorders, an altered enteral immune response and altered mucosal functions, which manifest themselves in an impaired intestinal barrier and secretion, as well as visceral hypersensitivity. In relation to visceral hypersensitivity, altered signal processing in brain regions responsible for emotional or sensorimotor processing of visceral signals has been identified at the neurological level [12]. This finding may provide a plausible explanation for the association between IBS and psychological factors and further highlights the importance of the gut-brain axis in the pathophysiology of IBS [13].

In terms of such gut-brain axis involvement, reduced parasympathetic activation appears to be detectable, particularly in patients with diarrhea-predominant IBS (IBS-D), whereby this reduced activation could in turn be associated with the extent of symptoms, experiences of abuse and symptoms of depression [14]. A large number of studies further demonstrate sympathetic overactivation in patients with IBS [15], which in turn appears to be associated with increased stress levels [16]. In addition, those affected by IBS show stress-induced changes in gastrointestinal motility, autonomic tone and the HPA axis response, among other things, against the background of an altered gut-brain axis [17].

Recently, the influence of the microbiome on the gut-brain axis has also been studied in more detail in relation to the development and maintenance of IBS [18]. Here, changes in both the quantity and quality of the total intestinal bacteria have been found in patients with IBS [18], and stress and the intestinal bacterial flora may in turn interact with each other and influence, for example, the visceral pain perception of patients with IBS [19]. The changes in the microbiome in IBS sufferers could also provide an explanation for the effects of infections and antibiotic therapies in the development of IBS.

With regard to genetic predispositions, IBS tends to run in families, in some cases over several generations: the probability of developing IBS in a relative of an IBS sufferer is about two to three times higher [20]. Initial study results also suggest that epigenetic factors could also be involved in the genesis of IBS [21].

High comorbidity with affective disorders, especially anxiety and depressive disorders, is well documented in IBS [22]. Chronic stress and psychological comorbidities are considered risk factors for the development and maintenance of IBS [23]. Thus, increased anxiety and depressive symptoms [24] and reduced quality of life [25] have been shown to be predictors of initial manifestation of IBS. Furthermore, the prevalence of stressful life events in the past (e.g. experiences of abuse or childhood trauma) is increased in comparison to healthy subjects [26]. It has also been shown that psychometrically recorded anxiety and depressive symptoms correlate positively with the extent of pain [27] and can have a negative effect on the feeling of fullness and bloating [28]. However, anxiety and depressive disorders may also develop secondarily as a result of the stress of chronic gastrointestinal symptoms [24]. In addition, aspects of coping with the disease or coping strategies in dealing with stress and symptoms (especially catastrophizing) as well as disease behavior learned through the social environment (e.g., interpretation of body perceptions as “problematic symptoms,” maladaptive avoidance behavior, etc.) seem to play an important role in the development and maintenance of IBS [29–31]. The influence of personality traits is also taken into account in some studies: the Neuroticism personality scale in particular appears to play a role and should be investigated further in terms of vulnerability to developing IBS [31].

In summary, against the background of a biopsychosocial model, complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle seem to be obvious in the pathogenesis of IBS [32].

Note: The biopsychosocial model takes into account various somatic and psychosocial factors within the pathophysiology of IBS and integrates their multifaceted interaction processes. Thus, numerous biological alterations have since been identified that are associated with IBS symptomatology. The gut-brain axis in particular offers a plausible explanation for the association between IBS and psychological factors. Complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle appear to be obvious here.

Therapy

Corresponding to a very heterogeneous clinical picture in terms of pathogenesis, manifestation of symptoms and the resulting impairments in everyday life, there is also a very broad spectrum of potentially effective treatment principles against the background of the biopsychosocial disease model. As a result of this heterogeneity, it is not possible to name “the” standard therapy for IBS; rather, each therapeutic intervention initially has a probationary character. In accordance with the S3 guideline, combinations of different medicinal substances as well as combinations of medicinal and non-medicinal treatments should be considered if there is only a partial response to monotherapy and/or for the treatment of various symptomatic complaints [7]. These treatment components are discussed in more detail below.

Note: According to the updated S3 guideline, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts should be used in the treatment of IBS if there is only a partial response to monotherapy and/or for the treatment of various symptoms.

Lifestyle: The current data situation regarding evidence-based recommendations on favorable lifestyle changes (e.g. no smoking, little alcohol, conscious eating, sufficient exercise, enough sleep, stress reduction, etc.) is currently sparse and (despite some positive observations) still contradictory [33]. A review published in 2022, based on fewer high-quality studies, came to the conclusion that physical exercise in particular, such as yoga or treadmill training, can improve the symptoms of IBS [34]. Other frequently recommended forms of physical activity for patients with IBS are walking, cycling, swimming and aerobics [35].

Note: Physical exercise can have a have a positive effect on IBS symptoms.

Nutrition/diet: According to the S3 guideline, nutritional medicine/nutritional therapy measures are a meaningful component of a therapy concept for patients with IBS [7]. If pain, bloating and diarrhea are the dominant symptoms, a low-FODMAP diet should be recommended according to the guidelines [7]. Fermentable oligo-, di- and monosaccharides and polyols (FODMAPs) are short-chain carbohydrates that are sometimes insufficiently or poorly absorbed in the small intestine. They are then fermented and osmotically active in the large intestine at the latest, which can result in abdominal pain, bloating and soft, bulky stools. In a low-FODMAP diet, FODMAPs are initially avoided in the food intake (elimination phase) with accompanying medical nutritional advice. As soon as the symptoms improve as a result of the elimination phase, foods with a higher FODMAP content can be gradually reintroduced. According to this scheme, it is possible to find out which foods trigger or worsen symptoms and which are tolerated (phase of tolerance finding). All foods that could be eaten without symptoms are then included in the long-term diet plan (long-term diet phase) [36]. A review published in 2022 based on 13 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) was able to demonstrate an improvement in IBS symptoms with a restriction of FODMAPs [37]. For IBS with predominantly obstipative symptoms (IBS-O), the guideline recommends an increased intake of dietary fiber (preferably soluble) [7]. Several reviews have already confirmed improvements in symptoms as a result of an increased intake of soluble fiber [38,39].

Note: The so-called “low FODMAP diet” in particular has been shown to alleviate IBS symptoms. However, it should only be used for a limited period of time and with accompanying medical nutritional advice.

Symptom-oriented medication: Pharmacotherapy of IBS should always be symptom-oriented and take into account the dominant symptoms [7]. According to the guideline, medication with the peristaltic inhibitor loperamide (µ-opioid receptor agonist) is recommended for the treatment of IBS-D. Despite good evidence of efficacy, the updated guideline states that eluxadoline, which is also opioid-based, should only be considered in selected individual cases of otherwise refractory IBS-D, as its use appears to be associated with acute pancreatitis, among other things, and should not be used in patients after cholecystectomy, with bile duct disease, alcohol abuse, liver cirrhosis and sphincter Oddi dysfunction in particular. The cholesterol absorption inhibitor colestyramine should be used to treat chologenic diarrhea. Colesevelam can also be used against the same pathophysiological background. Furthermore, an “off-label” therapy with 5-HT3 antagonists (e.g. ondansetron) should be tried in the case of otherwise refractory IBS-D [7].

Macrogol-type laxatives are recommended for the treatment of constipation symptoms. If there is no response to conventional laxatives or if they are not tolerated, the 5-HT4 agonist prucalopride should be tried for treatment. Furthermore, the peptide drug linaclotide (guanylate cyclase C agonist) should be recommended for laxative-refractory constipation and especially for concomitant abdominal pain and flatulence, but treatment is not reimbursed in Germany. Lubiprostone from the group of chloride channel activators should only be considered in selected individual cases of otherwise therapy-refractory RDS-O due to the lack of approval and limited availability in Germany [7].

According to the S3 guideline, spasmolytics such as butylscopolamine should be recommended for the treatment of pain associated with IBS [7]. Furthermore, the antibiotic rifaximin, which is not approved for this indication in Germany, should be considered for the treatment of bloating symptoms in otherwise refractory IBS without constipation [7].

Note: Drug therapy for IBS should always be symptom-oriented and take into account the dominant symptoms. For example, peristaltic inhibitors are primarily used for IBS-D and macrogol-type laxatives are primarily used for the treatment of constipation symptoms. In the treatment of IBS-associated pain, spasmolytics such as butylscopolamine are the main drugs used.

Probiotics: With regard to the general efficacy of probiotics for the treatment of IBS-associated symptoms, no reliable statement can be made at present due to the great methodological and qualitative heterogeneity of the study situation [7]. However, according to the guideline, selected probiotics should be used in the treatment of IBS, whereby each treatment trial with probiotics should initially be carried out on a trial basis and only continued after convincing relief of symptoms [7]. In a review published in 2022, Lactobacillus in particular was shown to be demonstrably effective in alleviating IBS symptoms [40]. A currently discussed mechanism of action of probiotics is based on the finding that certain probiotic strains such as Lactobacillus reduce intestinal hypersensitivity by increasing the release of μ-opioid and cannabinoid receptors [41]. Nevertheless, the mechanisms of action of probiotic microorganisms are not yet sufficiently understood [42].

Note: Individual probiotic strains and multispecies products have already been proven to be effective, but a general effectiveness of probiotics has not yet been proven, so that every treatment attempt with probiotics is initially of a trial nature.

Phytotherapy: Peppermint oil in particular from the group of phytotherapeutics has already been shown in several reviews and meta-analyses to be effective in the treatment of abdominal pain associated with IBS [43,44] and should therefore be considered according to the guideline [7]. Other phytotherapeutic preparations (such as the plant mixture STW-5 and STW-5-II [45]) were able to achieve symptom relief, particularly of abdominal pain, in individual RCT studies and should be individually integrated into the treatment concept [7].

Note: In the group of phytotherapeutics, peppermint oil in particular has proven to be demonstrably effective.

Psychotropic drugs: The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline is the most frequently investigated medication for pain in IBS-D [46] and, according to the guideline, should be used in adults for the treatment of IBS-associated pain [7]. Furthermore, as tricyclic antidepressants prolong orocecal as well as total gastrointestinal transit time, it seems appropriate to use tricyclics in IBS-D but not in IBS-O as it could aggravate constipation [46,47]. Furthermore, it should not be used in elderly patients if possible due to the anticholinergic side effects [7]. In contrast, SSRI-type antidepressants shorten orocecal transit time, so it seems reasonable to use them in RDS-O. However, as the study situation on the use of SSRIs in IBS has so far provided inconsistent results [48] and, moreover, there is no approval for the use of SSRIs for IBS in Germany, the updated guideline states that SSRI-type antidepressants can only be used in cases of psychological comorbidity. In addition, the use of the serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) duloxetine can be considered in adults with comorbid anxiety and depressive disorders [49].

Note: The tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline in particular is used in adults with IBS-D associated pain. According to the updated guideline, SSRI-type antidepressants can be considered in cases of psychological comorbidity.

Psychotherapy: According to the S3 guideline, psychoeducational elements, such as providing information about IBS and the connection between stressful emotions and the occurrence of symptoms, are useful as a cost-effective offer as part of other treatment [7], as they have been shown to have a positive effect on the symptoms and quality of life of patients with IBS [9]. In addition, strategies for dealing with stress and/or coping with illness should be recommended individually as adjuvant measures in the sense of guided self-help measures [50].

Specialist psychotherapeutic procedures should be offered as part of the treatment concept as an additional service if indicated [7]. Regarding the basic indication for psychotherapy, independent of the respective procedure, the patient’s wish, a significantly impaired quality of life due to gastrointestinal symptoms, and any psychological comorbidities are decisive [50]. If psychotherapy is indicated, it can be combined with psychopharmacotherapy if necessary [50].

There is already extensive evidence for the effectiveness of psychotherapy for IBS [50–52]. Most studies have been published on cognitive behavioral therapy, which has been shown to be effective [52,53]. However, a meta-analysis based on 18 RCTs found no superiority compared to other therapy methods [53]. Fewer studies exist on psychodynamic procedures, but they too have been shown to be effective [51]. Mindfulness-based forms of therapy have also shown initial positive effects [52], but due to the currently still limited number of studies, the guidelines do not yet make a conclusive recommendation for these [7].

Hypnotherapy has also been shown to be effective in alleviating IBS symptoms and improving the quality of life of those affected [52]. In particular, gut-directed hypnosis (GDH) is the only organ-specific psychotherapeutic procedure in the treatment of IBS [54]. Positive effects on symptom relief with medium effect sizes have been reported for GDH in several meta-analyses [55,56]. However, severe mental illnesses (e.g., severe depression and panic disorders) are considered relative contraindications in this regard.

In addition, there is growing evidence that online-based services (eHealth interventions) such as digital health applications (DIGAs) specifically for the treatment of IBS can have demonstrably positive effects on symptom severity and quality of life and thus represent a helpful, cost-effective and more accessible treatment option for IBS [57].

According to the guideline, relaxation therapy (e.g. progressive muscle relaxation according to Jacobson, autogenic training) should not be offered as monotherapy, but as part of a multimodal treatment concept [7]; the same applies to mindfulness-based yoga.

Note: Psychoeducational elements are demonstrably useful as a cost-effective offer as part of other treatment. Due to the repeatedly proven effectiveness of psychotherapy in IBS, specialist psychotherapeutic procedures should be offered as part of the treatment concept if there is a suitable indication (e.g. in the case of psychological comorbidity). Abdominal-directed hypnosis is used as an organ-specific psychotherapeutic procedure in the treatment of IBS.

Conclusion

The biopsychosocial model (Fig. 1) takes into account various somatic and psychosocial factors within the pathophysiology of IBS and integrates their multifaceted interaction processes. In addition, therapeutic starting points can be identified and implemented on a biological, psychological and social level. Against this background, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts seem particularly promising in the therapy of IBS and should be further investigated for their efficacy in clinical research.

Conflict of interest

AS is chairman of the German Society for Neurogastroenterology and Motility and has received consultancy and lecture fees from Bayer, Medice, Dr. Willmar Schwabe, Luvos, Microbiotica and Repha. The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Take-Home-Messages

- Irritable bowel syndrome is a somatoform/functional disorder of the lower digestive system, which is associated with persistent bowel-related symptoms such as abdominal pain, bloating and changes in bowel movements and causes considerable suffering for those affected.

- Based on a biopsychosocial model, it can be assumed that various somatic, psychological and social aspects are involved in the pathophysiology of IBS. Complex interaction processes between stress, psychological comorbidity and gastrointestinal symptoms in the sense of a vicious circle are obvious.

- The range of therapeutic interventions to treat the symptoms of IBS and improve the quality of life of those affected is correspondingly diverse. Therapeutic approaches can be identified and implemented on a biological, psychological and social level.

- Against this background, integrative and multimodal treatment concepts seem particularly promising in the therapy of IBS and should be further investigated for their efficacy in clinical research.

Literature:

- Mearin F, Lacy BE, Chang L, et al: Bowel disorders. Gastroenterology 2016 Feb 18; S0016-5085(16)00222-5.

- Lovell RM, Ford AC: Global prevalence of and risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2012; 10(7): 712-721.

- Halder SLS, Locke GR, Schleck CD, et al: Natural history of functional fastrointestinal disorders: A 12-year longitudinal population-based study. Gastroenterology 2007; 133(3): 799-807.

- Andrews EB, Eaton SC, Hollis KA, et al: Prevalence and demographics of irritable bowel syndrome: results from a large web-based survey. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2005; 22(10): 935-942.

- Lacy BE, Patel NK: Rome criteria and a diagnostic approach to irritable bowel syndrome. Journal of Clinical Medicine 2017; 6(11): 99.

- Gralnek IM, Hays RD, Kilbourne A, et al: The impact of irritable bowel syndrome on health-related quality of life. Gastroenterology 2000; 119(3): 654-660.

- Layer P, Andresen V, Allescher H, et al: Update S3 guideline irritable bowel syndrome: Definition, pathophysiology, diagnosis and therapy of irritable bowel syndrome of the German Society of Gastroenterology, Digestive and Metabolic Diseases (DGVS) and the German Society of Neurogastroenterology and Motility (DGNM) – June 2021. Journal of Gastroenterology 2021; 59(12): 1323-1415. AWMF registration number: 021/016.

- Spiller R, Aziz Q, Creed F, et al: Guidelines on the irritable bowel syndrome: mechanisms and practical management. Gut 2007; 56(12): 1770-1798.

- Weibert E, Stengel A: The role of psychotherapy in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol 2019; 69(9-10): 360-371.

- Enck P, Aziz Q, Barbara G, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2016; 2: 16014.

- Drossman DA: Functional gastrointestinal disorders: history, pathophysiology, clinical features, and Rome IV. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(6): 1262-1279.

- Mayer EA, Gupta A, Kilpatrick LA, Hong JY: Imaging brain mechanisms in chronic visceral pain. Pain 2015; 156: 50-63.

- Raskov H, Burcharth J, Pommergaard HC, Rosenberg J: Irritable bowel syndrome, the microbiota and the gut-brain axis. Gut Microbes 2016; 7(5): 365-383.

- Mazurak N, Seredyuk N, Sauer H, et al: Heart rate variability in the irritable bowel syndrome: a review of the literature. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2012; 24(3): 206-216.

- Liu Q, Wang EM, Yan XJ, Chen SL: Autonomic functioning in irritable bowel syndrome measured by heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Journal of Digestive Diseases 2013; 14(12): 638-646.

- Heitkemper M, Jarrett M, Cain K et al: Increased urinary catecholamines and cortisol in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol 1996; 91(5): 906-913.

- Chang L: The role of stress on physiological responses and clinical symptoms in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol 2011; 140(3): 761-765.

- Kennedy PJ, Cryan JF, Dinan TG, Clarke G: Irritable bowel syndrome: a microbiome-gut-brain axis disorder? World J Gastroenterol 2014; 20(39): 14105-14125.

- Moloney RD, Johnson AC, O’Mahony SM, et al: Stress and the microbiota-gut-brain axis in visceral pain: relevance to irritable bowel syndrome. CNS Neurosci Ther 2016; 22(2): 102-117.

- Saito YA: The role of genetics in IBS. Gastroenterol Clin North Am 2011; 40(1): 45-67.

- Dinan TG, Cryan J, Shanahan F, et al: IBS: An epigenetic perspective. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 7(8): 465-471.

- Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR: Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology 2002; 122(4): 1140-1156.

- Tanaka Y, Kanazawa M, Fukudo S, Drossman DA: Biopsychosocial model of irritable bowel syndrome. J Neurogastroenterol Motil 2011; 17(2): 131-139.

- Koloski NA, Jones M, Kalantar J, et al: The brain–gut pathway in functional gastrointestinal disorders is bidirectional: a 12–year prospective population–based study. Gut 2012; 61(9): 1284-1290.

- Ford AC, Forman D, Bailey AG, et al: Irritable bowel syndrome: a 10-yr natural history of symptoms and factors that influence consultation behavior. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(5): 1229-1239.

- Chitkara DK, van Tilburg MAL, Blois-Martin N, Whitehead WE: Early life risk factors that contribute to irritable bowel syndrome in adults: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol 2008; 103(3): 765-774.

- Elsenbruch S, Rosenberger C, Enck P, et al: Affective disturbances modulate the neural processing of visceral pain stimuli in irritable bowel syndrome: an fMRI study. Gut 2010; 59(4): 489-495.

- Van Oudenhove L, Törnblom H, Störsrud S, et al: Depression and somatization are associated with increased postprandial symptoms in patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology 2016; 150(4): 866-874.

- Drossman DA, Leserman J, Li Z et al: Effects of coping on health outcome among women with gastrointestinal disorders. Psychosom Med 2000; 62(3): 309-317.

- Van Oudenhove L, Crowell MD, Drossman DA, et al: Biopsychosocial aspects of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology 2016; S0016-5085(16)00218-3.

- Lackner JM, Gudleski GD, Thakur ER, et al: The impact of physical complaints, social environment, and psychological functioning on IBS patients’ health perceptions: looking beyond GI symptom severity. Am J Gastroenterol 2014; 109(2): 224-233.

- Blanchard EB, Lackner JM, Jaccard J, et al: The role of stress in symptom exacerbation among IBS patients. J Psychosom Res 2008; 64(2): 119-128.

- Kang SH, Choi SW, Lee SJ, et al: The effects of lifestyle modification on symptoms and quality of life in patients with irritable bowel syndrome: a prospective observational study. Gut Liver 2011; 5(4): 472-477.

- Nunan D, et al: Physical activity for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2022; 6(6): Cd011497.

- Radziszewska M, Smarkusz-Zarzecka J, Ostrowska L: Nutrition, Physical Activity and Supplementation in Irritable Bowel Syndrome. Nutrients 2023; 15(16).

- Hetterich L, Stengel A: Nutritional aspects in irritable bowel syndrome – an update. Current Nutritional Medicine 2020; 45(4): 276-285.

- Black CJ, Staudacher HM, Ford AC: Efficacy of a low FODMAP diet in irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2022; 71(6): 1117-1126.

- Moayyedi P, et al: The effect of fiber supplementation on irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. American Journal of Gastroenterol 2014; 109(9): 1367-1374.

- 39 Nagarajan N, et al: The role of fiber supplementation in the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2015; 27(9): 1002-1010.

- Xie CR, et al: Low FODMAP Diet and Probiotics in Irritable Bowel Syndrome: A Systematic Review with Network Meta-analysis. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2022; 13: 853011.

- Shrestha B, et al: The role of gut-microbiota in the pathophysiology and therapy of irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Cureus 2022; 14(8): e28064.

- Sharma S, et al: Probiotics in irritable bowel syndrome: A review article. Cureus 2023; 15(3): e36565.

- Ingrosso MR, et al: Systematic review and meta-analysis: efficacy of peppermint oil in irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2022; 56(6): 932-941.

- Khanna R, MacDonald JK, Levesque BG: Peppermint oil for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology 2014; 48(6): 505-512.

- Madisch A, et al: Treatment of irritable bowel syndrome with herbal preparations: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, multi-centre trial. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics 2004; 19(3): 271-279.

- Lambarth A, Zarate-Lopez N, Fayaz A: Oral and parenteral anti-neuropathic agents for the management of pain and discomfort in irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurogastroenterology & Motility 2022; 34(1): e14289.

- Hetterich L, Zipfel S, Stengel A: Gastrointestinal somatoform disorders. Fortschr Neurol Psychiatr 2019; 87(9): 512-525.

- Bundeff AW, Woodis CB: Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors for the treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Annals of Pharmacotherapy 2014; 48(6): 777-784.

- Ford AC, Lacy BE, Harris LA, et al: Effect of antidepressants and psychological therapies in irritable bowel syndrome: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Official journal of the American College of Gastroenterology 2019; 114(1): 21-39.

- Hetterich L, Stengel A: Psychotherapeutic interventions in irritable bowel syndrome. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2020; 11: 286.

- Black CJ, Thakur ER, Houghton LA, et al: Efficacy of psychological therapies for irritable bowel syndrome: systematic review and network meta-analysis. Gut 2020; 69(8): 1441-1451.

- Slouha E, et al: Psychotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome: A systematic review. Cureus 2023; 15(12): e51003.

- Li L, et al: Cognitive-behavioral therapy for irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 2014; 77(1): 1-12.

- Bentele M, Stengel A: [Hypnotherapy for Irritable Bowel Syndrome]. Psychotherapy, Psychosomatics, Medical Psycholology 2022; 72(9-10): 452-460.

- Webb AN, Kukuruzovic RH, Catto-Smith AG, Sawyer SM: Hypnotherapy for treatment of irritable bowel syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007; 4: CD005110.

- Krouwel M, Farley A, Greenfield S, et al: Systematic review, meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of hypnotherapy for irritable bowel syndrome, effect of intervention characteristics. Complementary Therapies in Medicine 2021; 57: 102672.

- Brenner DM, Ladewski AM, Kinsinger SW: Development and current state of digital therapeutics for irritable bowel syndrome. Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2024; 22(2): 222-234.

GASTROENTEROLOGY PRACTICE 2024; 2(2): 6-12