Renowned representatives of the Swiss health care system discussed patient-centeredness, mismanagement of care, and the significance of guidelines in the area of tension between orientation and practicality. Digital solutions can effectively support doctor-patient communication, experience shows.

Prof. Dr. med. Christoph A. Meier, Medical Director Universitässpital Basel, addressed the question “Overuse, misuse et al.: What can we do?” in his lecture and presented the model of health care that focuses on the values assessed and weighted by the patient, such as various aspects of quality of life.

The Value-based Healthcare (VBHC) & Patient-reported Outcomes (PROMs) model is based on the theoretical foundations laid by Harvard economist Michael E. Porter twelve years ago [1]. One of his key statements is that in medicine it is generally the volume of services provided that is paid for, not the benefit (“value”) to the patient. Porter argues that actually the outcome should be measured according to the patient’s assessment. This raises the question of an appropriate approach, which the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) has been addressing since 2012 [2]. The consortium has developed metrics for 23 diseases that allow patient outcome to be measured in such a way that reliable comparability (“benchmarking”) is possible. The current 23 standard sets cover 54% of the global burden of disease and are being further developed in collaboration with the OECD [3].

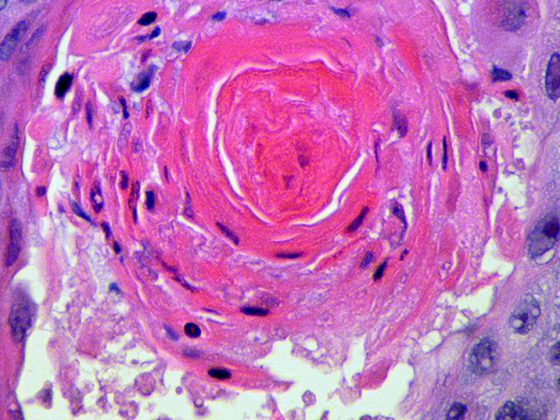

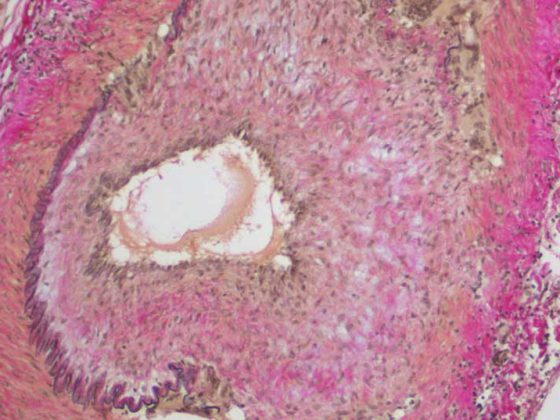

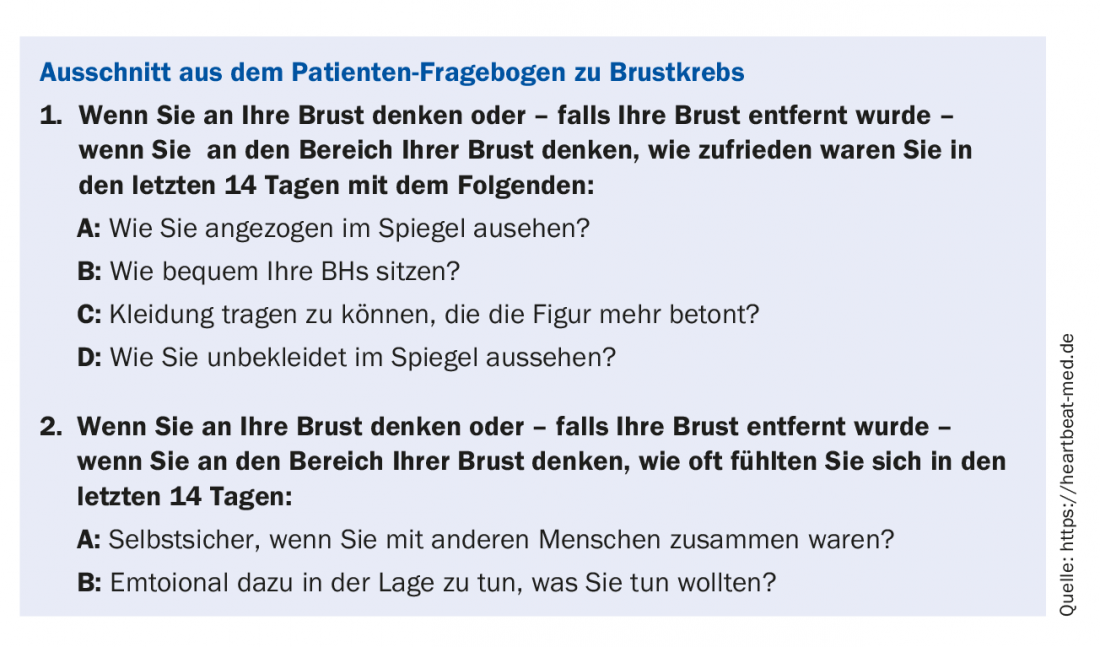

Meier went into more detail on the example of breast cancer: Typical disease-related metrics include recurrence, perioperative complications, infections, mortality, etc. In addition, these metrics also include important quality of life determining factors such as depression, fatigue, pain, body image, neuropathy, sexual dysfunction, and these are regularly recorded for up to ten years. [4] “That’s where you see if you’re doing good medicine or not,” Meier said.

Doctors hardly have time to ask questions like those in the sample questionnaire (box “Excerpt from the patient questionnaire on breast cancer”), Meier acknowledged. At Basel University Hospital, patients can fill out these questions directly in the waiting room using a tablet. The physician immediately sees the evaluation in graphical form. This allows the patient to articulate their needs and the physician to focus. At USB, ICHOM metrics will be implemented over the next few months on additional conditions such as Stroke, Anxiety & Depression Prostate Cancer. However, the approach of “value-based healthcare” would only come into play if this system also paid accordingly, Meier said, and continued: “It is no coincidence that this basic idea comes from Michael Porter as an economist: Medical services could, for example, be paid with a basic amount and additionally remunerated depending on the outcome metric. In this way, a change from “volume” to “value” could be initiated in our healthcare system.”

Benefits and limitations of guidelines

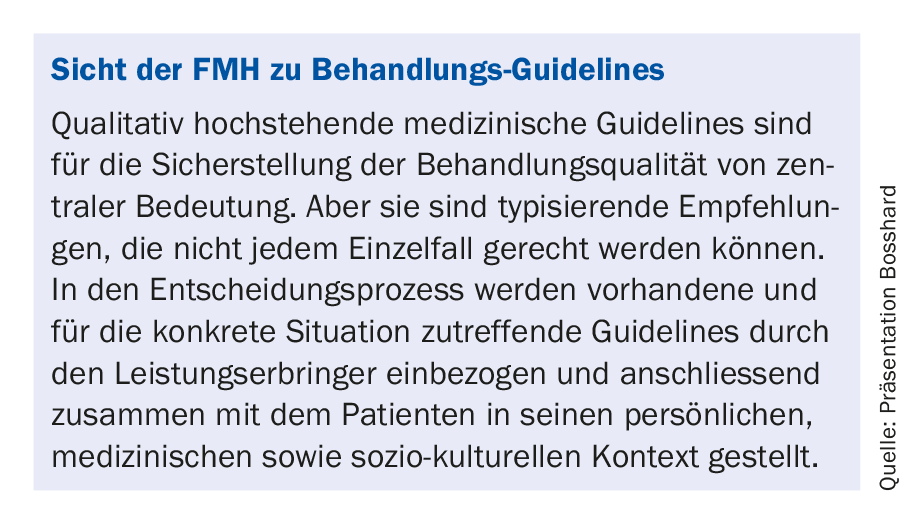

Christoph Bosshard, MD, Vice President of the FMH, spoke about the significance of guidelines with regard to patient-centered treatment: “Guidelines transfer the evidence-based findings from medical research to medical treatment recommendations. “Guidelines are important components in today’s medicine. They provide for knowledge transfer and ensure that the same diseases can be treated in the same way. Patients should thus have the same treatment opportunities. They also support political decisions such as the financing of healthcare services,” says Bosshard. The development of clinical decision support systems is also a known benefit of guidelines, he said. So much for the performance framework (see box “FMH’s view on treatment guidelines”).

In order to counteract the uncertainty caused by the variety of new guidelines, the FMH launched a platform “Guidelines Switzerland” last year [5]. Professional societies and organizations are now called upon to document their recommended guidelines. Metadata includes evidence level, scope, etc.

However, a challenge in medical practice is multimorbidity, for which the guidelines are hardly targeted, because their underlying randomized controlled trials have the characteristic of excluding multimorbid patients. Thus, guidelines have no validity for this situation. “Guidelines are disease-centric and not patient-centric, but it is clearly important in everyday life to treat patients, not diseases,” Bosshard cautioned.

Bosshard recommended that the effects of Guideline-compliant treatments be made available in registries (e.g., Patient Centered Outcome Registry PCOR) [6]. In addition, research on the topic of multimorbidity in elderly patients needs to be encouraged. Studies on the independence, effectiveness, applicability, and cost-effectiveness of guidelines are needed.

Multimorbidity in everyday dilemmas

Prof. Dr. med. Edouard Battegay FACP, Director of the Clinic and Polyclinic for Internal Medicine at the University Hospital Zurich (USZ), followed with his presentation on the topic of multimorbidity.

A 2012 Scottish study showed that multimorbidity is the most common disease constellation [7]: 50% of the population considers themselves healthy, 23% are multimorbid, and 19% are monomorbid. The age correlation to multimorbidity is clear. One in 50 children is also multimorbid. According to Battegay, 90% of emergency hospitalized patients in the USZ are severely multimorbid [8].

There are 10,000 ICD10 codes. This means that for three diagnoses, there are 1.8 quadrillion possible combinations. In reality, this is not quite as complicated as diseases occur in certain clusters and in combination with typical clusters [9]. “Social conditions also play a role in the presence of certain diseases,” Battegay gave the all-clear after this computational exercise.

Certain clinical pictures “collide” with each other. Often, therapy for one disease precludes that for another, e.g., necessary blood thinning for heart disease with concomitant brain hemorrhage. However, there are practically no guidelines on these “disease-disease interactions” (DDI). The current published guidelines may even be harmful, as Dr. Bossard pointed out, because they do not cover potential hazards from multimorbidity.

“Disease-Disease Interactions” can generate confusing complexity [10]. This cannot be easily solved at the moment. Interdisciplinary teamwork is a matter of organization, with internal medicine generalists coordinating specialists. Science, teaching, hospitals and the health care system assume monomorbidity and show corresponding process optimization and organizational structures. New thinking and research approaches are necessary, was also this conclusion.

Literature:

- Porter ME, Teisberg EO: Redefining health care: creating value-based competition on results. Harvard Business Press, Boston 2006.

- Kelley TA: International consortium for health outcomes measurement (ICHOM). Trials 2015; 16(3): O4.

- ICHOM.org: Our Standard Sets. www.ichom.org/

- medical-conditions, retrieved 13.3.2018

- Ong WL, Schouwenburg MG et al: A standard set of value-based patient-centered outcomes for breast cancer: the International Consortium for Health Outcomes Measurement (ICHOM) Initiative. JAMA Oncology 2017; 3(5): 677-685.

- FMH: Online platform “Guidelines Switzerland”: www.guidelines.fmh.ch

- Swiss Academy for Quality in Medicine SAQM: Service description “Patient Centered Outcome Registry (PCOR)”: https://www.fmh.ch/files/pdf18/PCOR_Leistungsbeschreibung.pdf

- Barnett K et al: Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional study. The Lancet 2012; 380(9836): 37-43.

- Kaplan et al: Prevalence of multimorbidity in medical inpatients. Swiss Med Wkly 2012; 142: w13533.

- Marengoni et al: Patterns of chronic multimorbidity in the elderly population. J AmGeriatr Soc 2009; 57: 225-230.

- Gassmann D et al: The Multimorbidity Severity Index (MISI). Medicine 2017; 96: 8(e6144).

HAUSARZT PRAXIS 2018; 13(5): 40-41