Lifestyle change is the first step in the treatment of type 2 diabetes. Diet and eating habits therefore play a very important role here. In view of the large number of diets, the question arises as to which of them can effectively combat the disease. Dutch scientists investigated how the regular use of a 5-day fasting-mimicking diet (FM D) in regular primary care for type 2 diabetes affects metabolic control and the prevention of complications.

Regular FMD programs lasting 4-7 consecutive days are designed to mimic the physiological effects of water-only fasting while minimizing its stress. They allow participants to eat light meals during the fasting period and restrict this to a limited number of days. This low-energy, plant-based formula diet consists mainly of complex carbohydrates and healthy fats. Due to the plant-based nature of the diet, it is low in protein, essential amino acids and sugar and relatively high in fiber and unsaturated fats. Aside from the low energy content, these characteristics are important for the intended fasting-mimicking effects of the diet (i.e., lowering serum glucose levels, IGF-1 and insulin, increasing insulin-like growth factor-binding protein-1 and ketone bodies, and reducing inflammatory markers). In healthy individuals (without diabetes), three 5-day cycles of FMD per month have been shown to reduce body fat mass, blood pressure, triglycerides and fasting blood glucose, particularly in individuals with high levels of these risk factors at baseline.

Dr. Elske L. van den Burg from the Department of Public Health and Primary Care, Leiden University Medical Centre (LUMC), the Netherlands, and colleagues investigated the clinical response to 5-day monthly FMD cycles as an adjunct to regular care versus regular care alone in people with type 2 diabetes in a real-world setting, i.e. under regular GP supervision and treatment [1] in a randomized, controlled and blinded trial. Eligible participants were people with type 2 diabetes, a BMI ≥27 kg/m2 and an age of >18 and <75 years. To be included in the study, participants also had to have an HbA1c value of >48 mmol/mol (6.5%) and be treated with lifestyle counseling only and/or lifestyle counseling plus metformin as the only blood glucose lowering agent, regardless of their HbA1c value.

Checks after 6 and 12 months

Both the control group and the FMD group received the usual care from their GP practice. This included a three-month clinical and biochemical assessment, lifestyle counseling with the option to consult a dietician, and medication adjustment if necessary. The adjustment of the dose of blood glucose-lowering medication was entirely at the discretion of the general practitioners, who followed the Dutch guidelines for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. The intervention group received 12 cycles of FMD on five consecutive days per month as an addition to their usual treatment. Participants were contacted by telephone once during each FMD period to support compliance. The FMD (commercially available) consisted of complete meal replacement products. The ingredients were all of plant origin and are generally considered safe. The energy content and macronutrient composition were as follows:

- Day 1 contained approx. 4600 kJ (approx. 1100 kcal; 10% protein, 56% fat, 34% complex carbohydrates);

- days 2-5 were identical and provided approx. 3150 kJ (approx. 750 kcal; 9% protein, 44% fat, 47% complex carbohydrates).

The diet of the participants who weighed more than 100 kg was supplemented with one chocolate crisp bar per day (approx. 375 kJ/90 kcal) with a similar macronutrient composition. The control group received only the usual supply. Compliance with the experimental plan was checked verbally every month. Primary and secondary outcomes were measured at baseline, 6 and 12 months, and 3 weeks after the last FMD cycle for FMD participants.

The primary outcomes were the changes in HbA1c and the dose of blood glucose-lowering medication compared to baseline. The medication effect score (MES) was used as an indirect measure of treatment with blood glucose-lowering medication. Secondary outcomes were body weight, BMI, total body fat, waist circumference, blood pressure, fasting plasma glucose, insulin and lipid profiles. In addition, plasma glucose and insulin concentrations in response to an oral glucose tolerance test (oGTT) were used to calculate the Matsuda index (reflecting insulin sensitivity) and the disposition index (reflecting endogenous insulin secretion). Adverse events (AEs) were recorded at two face-to-face visits at 6 and 12 months or, in the case of serious AEs, reported immediately.

16% were able to completely discontinue glucose-lowering medication

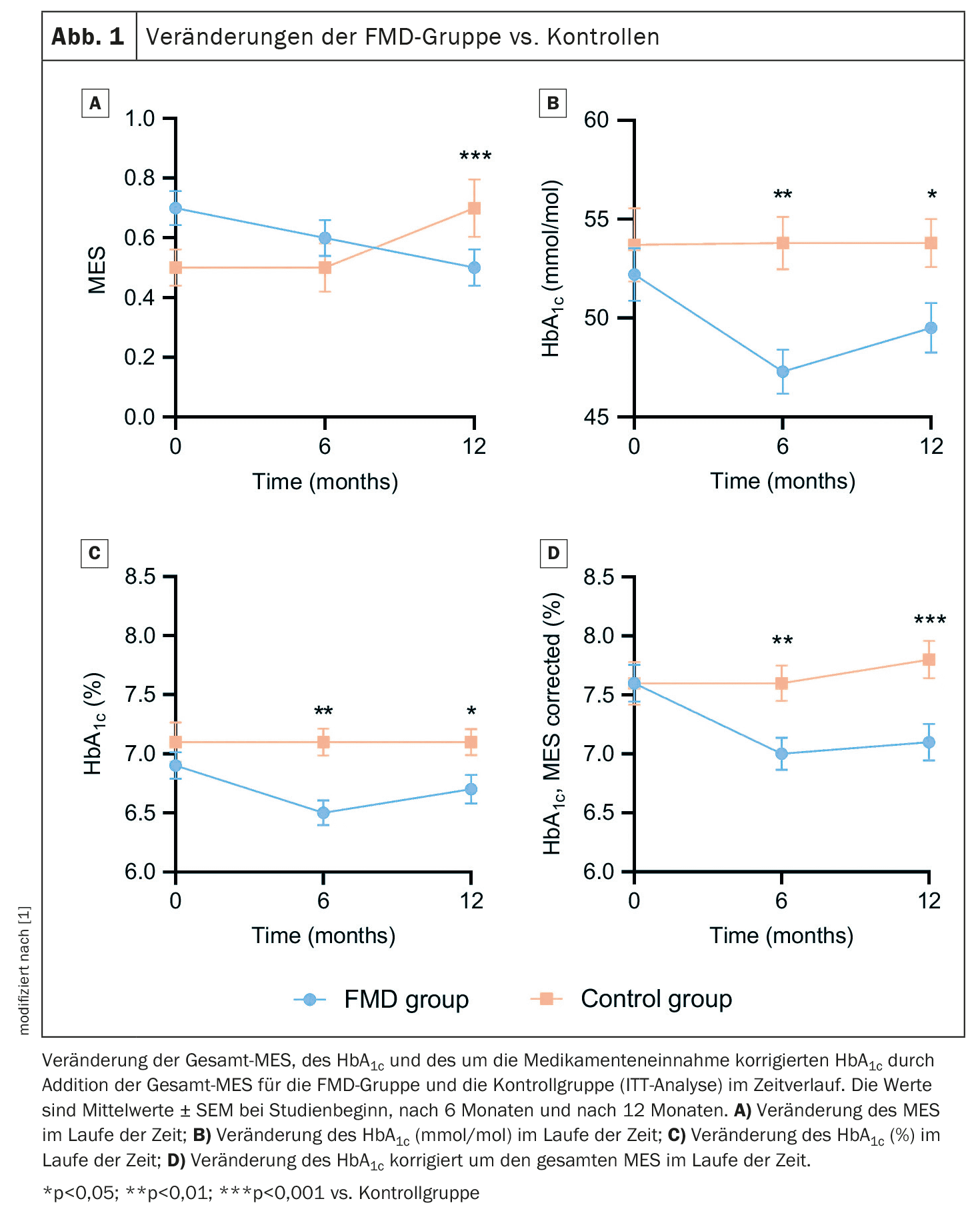

Data from 49 FMD participants and 43 control subjects were available for the intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis. Glucose-lowering medication use, as measured by the MES, decreased in the FMD group from 0.7 ± 0.4 (mean ± standard deviation, SD) at baseline to 0.5 ± 0.4 at 12 months, while it increased from 0.5 ± 0.4 to 0.7 ± 0.6 in the control group. This resulted in an adjusted estimated treatment effect of -0.3 (95% CI -0.4 to -0.2; p<0.001) (Fig. 1A). The results after 6 months were similar. Glucose-lowering medications were completely discontinued in 16% (n=7) of participants in the FMD group and 5% (n=2) of control participants (p=0.16), while additional medications were prescribed in 2% (n=1) of the FMD group and 26% (n=10) of controls (p=0.006). HbA1c levels decreased from 52.2 ± 9.3 mmol/mol (6.9 ± 0.8%) (mean ± SD) at baseline to 49.5 ± 8.2 mmol/mol (6.7 ± 0.8%) at 12 months in the FMD group. They increased in the control group, resulting in adjusted estimated treatment effects of -3.2 mmol/mol (95% CI -8.0 to -2.0) and -0.3% (95% CI -0.6 to -0.0) (p=0.04) (Fig. 1B+C).

As the primary outcome measures, blood glucose-lowering medication and HbA1c, influence each other, they were combined in two different ways to better reflect glycemic control, the authors explain. HbA1c adjusted for drug treatment (%) decreased from 7.6 ± 1.1% (mean ± SD) at baseline to 7.1 ± 1.0% at 12 months in the FMD group by adding the total TRS, but increased from 7.6 ± 1.2% at baseline to 7.8 ± 1.0% in the control group, giving an adjusted estimated treatment effect of -0.6% (95% CI -0.9 to -0.3; p<0.001) (Fig. 1D). In addition, glycemic management improved in 53% of FMD participants vs. 8% in controls, remained stable in 23% vs. 33% and worsened in 23% vs. 59% (p<0.001).

Improvement in insulin resistance

The authors emphasize that the proportion of participants in whom glucose-lowering medication was reduced was eight times higher in the FMD group (40%) than in the control group (5%). Interestingly, HbA1c levels decreased by ≥5 mmol/mol (0.5%) in 42% of participants in the FMD group despite reduced medication intake, while this was only the case in 15% of controls. In addition, average body weight, body fat percentage and waist circumference decreased more in the FMD program participants than in the control participants, while fat-free mass did not change. The anthropometric changes were accompanied by an improvement in insulin resistance, as shown by the Matsuda index.

In general, the diet program was well tolerated, as shown by the similar number of (mild to moderate) adverse events and discontinuation rates in the groups. However, it should be noted that a number of (minor) complaints were reported during calls while using the diet, which caused five participants to discontinue the FMD. According to the authors, it might be advisable to warn FMD participants about possible transient signs of energy deficit (fatigue, dizziness, headaches). Despite these problems, the majority of participants remained motivated and adhered to the program.

The authors conclude that integrating a monthly FMD program without additional lifestyle counseling into the regular care of people with type 2 diabetes taking metformin reduces the need for blood glucose-lowering medication and lowers HbA1c levels.

Take-Home-Messages

- Regular use of FMD significantly reduces the need for blood glucose-lowering medication and improves the HbA1c value compared to regular standard treatment alone.

- Regular use of FMD improves blood glucose management compared to regular treatment in a significant proportion of participants.

- Regular use of FMD reduces body weight, BMI, waist circumference and body fat percentage compared to regular care alone.

- Integrating FMD programs into routine primary care for type 2 diabetes improves anthropometric readings, facilitates glycemic control and reduces the burden of taking medication without the need for (additional) daily lifestyle changes.

Literature:

- van den Burg EL, Schoonakker MP, van Peet PG, et al.: Integration of a fasting-mimicking diet programme in primary care for type 2 diabetes reduces the need for medication and improves glycaemic control: a 12-month randomised controlled trial. Diabetologia 2024; 67: 1245–1259; doi: 10.1007/s00125-024-06137-0.

InFo DIABETOLOGIE ENDOKRINOLOGIE 2024; 1(3): 18–20