A number of treatment options are available today for patients with chronic heart failure. It is not always easy to make the right choice.

Advances in medical treatment, especially of acute coronary syndrome, have led to a steady increase in the prevalence of chronic heart failure in the recent past – currently affecting about 26 million worldwide and about 200,000 patients in Switzerland. Since the course of the disease can only be delayed, but the underlying disease cannot be reversed, more and more patients, even younger ones, reach a severely symptomatic stage with severely impaired quality of life and high one-year mortality.

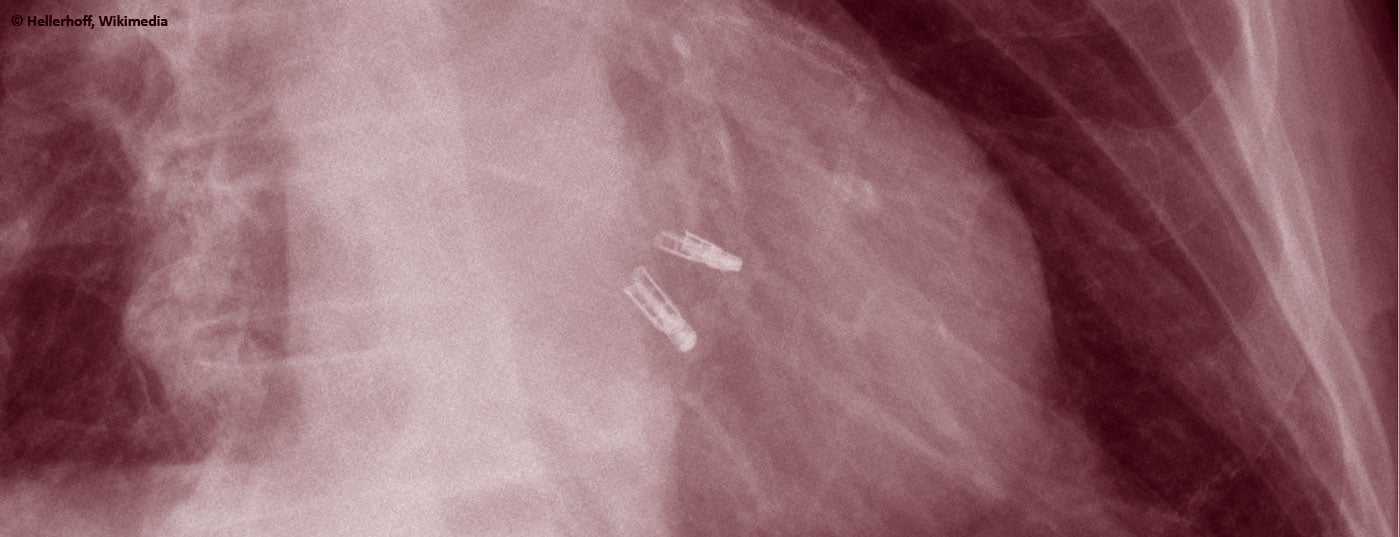

Deciding which patient should receive which further therapy, and when, is one of the most difficult tasks here. Heart transplantation usually provides a very good quality of life and patients have excellent long-term survival (after 12.4 years, 50% of transplanted patients are still alive [ISHLT]). However, due to the continuing shortage of donor organs, this treatment can only be offered to a few selected and mostly younger patients. Moreover, with an average waiting time of 1-2 years, transplantation is not an option in the acute situation; mechanical circulatory support with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) may then be considered as a long-term therapeutic alternative (destination therapy) or bridge (bridge-to-transplant). T. Carrel and D. Reineke have published in the

last issue

gave a good overview of mechanical circulatory support in acute and chronic heart failure.

Who benefits from an artificial heart and how does one recognize the optimal time for such therapy?

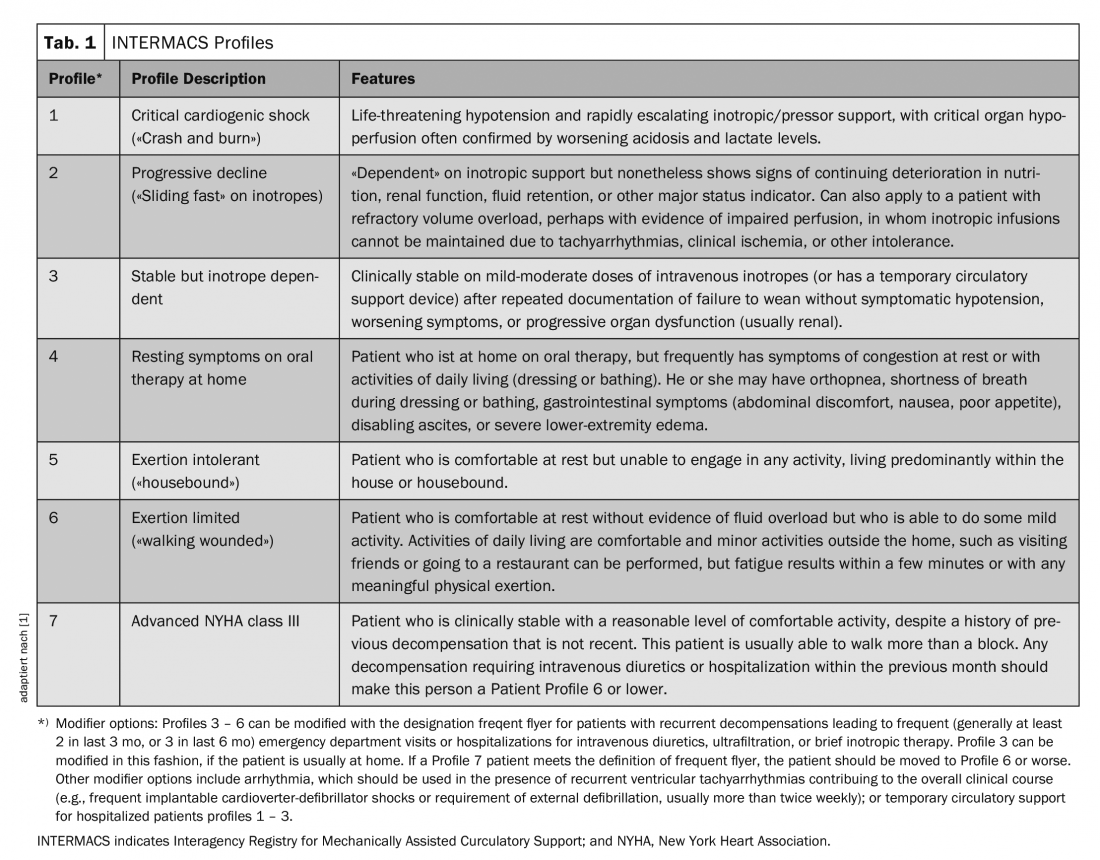

In recent years, patients in INTERMACS (IM) categories 1-3 have been primarily considered for implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) (Tab.1). That is, patients with critical cardiogenic shock (IM profile 1), rapid deterioration despite maximal intensive medical therapy (IM profile 2), or those who cannot be weaned from therapy with inotropics (IM profile 3); i.e., those patients for whom out-of-hospital survival would not have been possible without further therapy.

The largest registry of patients with mechanical support devices is maintained by the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Mechanical Circulatory Support Registry (IMACS). It includes data from 35 countries as well as the major registries from Europe (EUROMACS), the United States (INTERMACS), and Japan (J-MACS) [2]. Between January 2013 and December 2016, a total of 14,062 device implantations were registered, of which 93% were pure LVADs, 5% were biventricular assist devices, and 2% were “total artificial hearts.” Eighty-three percent of patients were in IM category 1-3, nearly 28% were actively listed for heart transplantation, and 41% received an LVAD as definitive therapy (destination therapy).

One- and two-year survival rates were 81% and 71%, respectively, in patients after LVAD implantation with continuous flow. Patients with IM profile 1 had significantly worse one-year survival than those with IM 3 (71% vs. 84%), and the best two- and three-year survival was seen in patients with IM profile 5-7, i.e., ambulatory patients with severe heart failure.

Are we waiting too long?

The ROADMAP study addressed this question by including 200 outpatients with severe heart failure (IM profile ≥4, walking distance on 6 min walk test (6 MWT) <300 meters, at least one hospitalization, or two emergency department presentations for heart failure in the past year) who did not qualify for heart transplantation were included in this prospective, nonrandomized multicenter study [3]. Patients, together with their physicians, were able to choose between optimal medical therapy (OMT) or LVAD implantation (destination therapy). The primary endpoint was survival on the initially chosen therapy and an improvement of 75 meters or more in the 6 MWT. Secondary endpoints included quality of life (EuroQol 5 dimensions, 5-level questionnaire, EQ-5D-5L) and depression score (Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) by questionnaire, NYHA class, and adverse events.

As expected, patients who initially opted for LVAD were sicker overall and had poorer quality of life (LVAD group vs. OMT group: quality of life (EQ-5D VAS) 44 vs. 66 points, depression (PHQ-9 score) 10 vs. 7 points, NYHA IV 52% vs. 25%, Intermacs profile 4 65% vs. 34%, IM 5 or higher 32% vs. 64%).

Despite the less favorable baseline, more patients showed improvement in exercise capacity to NYHA class I/II two years after LVAD implantation (69% vs. 37% under OMT) and walking distance increased significantly. Furthermore, patients reported a significant improvement in quality of life (EQ-5D VAS +27Pkt) and mood (Depression Scores PHQ 9 Score -4.6Pkt). No significant change was detected in the OMT group.

Interestingly, however, almost a quarter of patients in the OMT group (21%) opted for LVAD implantation within the next two years, at a median of 4.9 months after inclusion. More than half of the patients (55%) with delayed LVAD implantation were already on therapy with inotropic agents at this time, 70% had reached NYHA stage IV, and median walking distance decreased from an initial 219 m to 90 m.

When this relatively large group of patients with delayed LVAD implantation is added to the OMT (intention-to-treat) group, there is no significant difference in survival between the two groups. However, when separated by the actual therapy received, we see that only 41% of the OMT group but 70% of the LVAD group survived on the original therapy.

The number of adverse events (AEs) was higher in the LVAD group than in the OMT group. The most common AEs after LVAD implantation were bleeding, driveline infections, pump thrombosis, and stroke; in the OMT group, mainly worsening heart failure (50% of patients). Surprisingly, despite AEs and more frequent hospitalizations (86% vs. 78%), patients with LVAD reported better quality of life and mood.

Dividing the patients according to the severity of their disease, we see that patients with IM 4 benefited most, while those with IM 5-7 benefited only if they had previously reported impaired quality of life.

Summarizing all the findings of this study, it can be said that patients with IM 5-7 who report an acceptable quality of life can wait with implantation without risking excessive mortality as long as they are monitored regularly and closely at a center (median deterioration occurred after only 4.9 months in this study).

Therapy optimization before LVAD implantation

Since the implementation of the ROADMAP trial and the last IMACS Registry data collection in 2016, newer drug (sacubitril-valsartan) and interventional (MitraClip®, atrial fibrillation ablation) therapies have become more widely used in daily practice. In the PARADIGM-HF trial, sacubitril-valsartan therapy was associated with a relative reduction in mortality and heart failure hospitalizations of 20% in fewer patients (only less than 1% had NYHA IV, the majority approximately 70% had NYHA II) compared with enalapril therapy [4]. In CASTLE-AF, in a highly selected group of patients with heart failure and atrial fibrillation, a relative reduction of 38% in the combined end point of death and rehospitalization due to heart failure was found after atrial fibrillation ablation [5]. The COAPT Trial demonstrated a reduction in mortality (RRR -38%) and rehospitalization rate due to HI (RRR -47%) after MitraClip® implantation compared to medical therapy in patients with severe secondary mitral regurgitation and heart failure [6]. Although certainly not all patients benefit from these therapies, we have more and more options available to help these seriously ill patients.

However, there have also been many technical developments in recent years that have reduced the complication rate after LVAD implantation. On the one hand, more recent data allow for a more optimal management of patients (for example, in the ENDURANCE Supplemental Trial, a significant reduction in stroke rate was achieved through better blood pressure control), and on the other hand, technical changes have also become apparent with the latest generation of the LVAD (HeartMate 3®, Abbott) [7]. In the MOMENTUM 3 study, implantation of the HeartMate 3® (a centrifugal pump) resulted in a significantly reduced overall stroke rate (10% vs. 19%, with the number of major strokes (modified Rankin score of >3) remained the same), as well as a significantly lower rate of possible or confirmed pump thrombosis (1.1% vs. 15.7%) compared to the HeartMate 2®. Not a single HeartMate 3® had to be replaced or explanted due to suspected pump thrombosis, whereas this was the case in 12% of patients with HeartMate 2® [8].

The optimized therapy for every patient

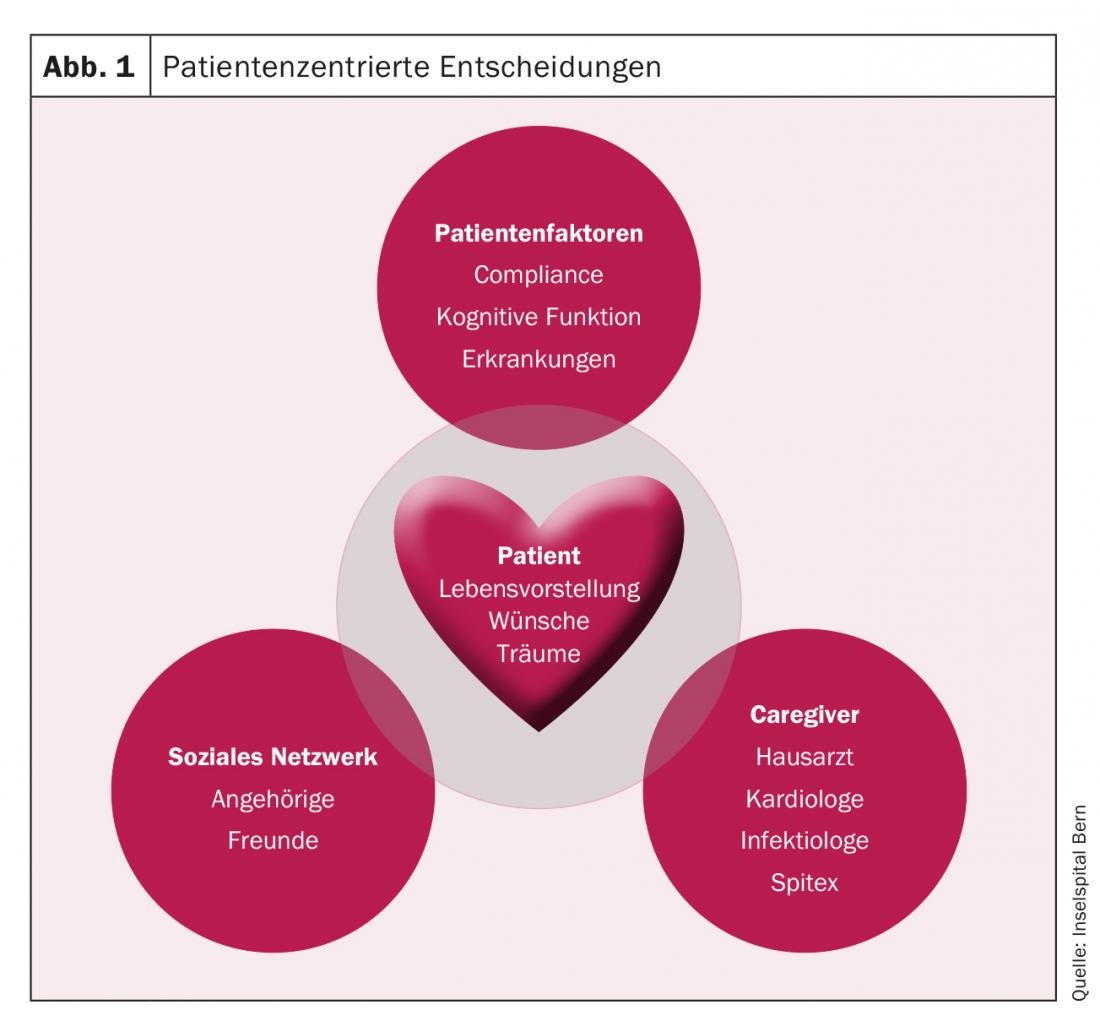

With all the technical, interventional and drug options available, we can now offer patients with heart failure many more options than in the past. At the same time, this also brings with it the obligation to find the most suitable therapy for each patient. In order to give the patient and his or her family the opportunity to consider all the given advantages and disadvantages of each therapy in peace and to perform interventions, if desired, in an elective setting, it is important to get to know the patients at an early stage at a center for severe heart failure and to coordinate further care together with the treating primary care physicians, cardiologists, and other involved persons in the environment.

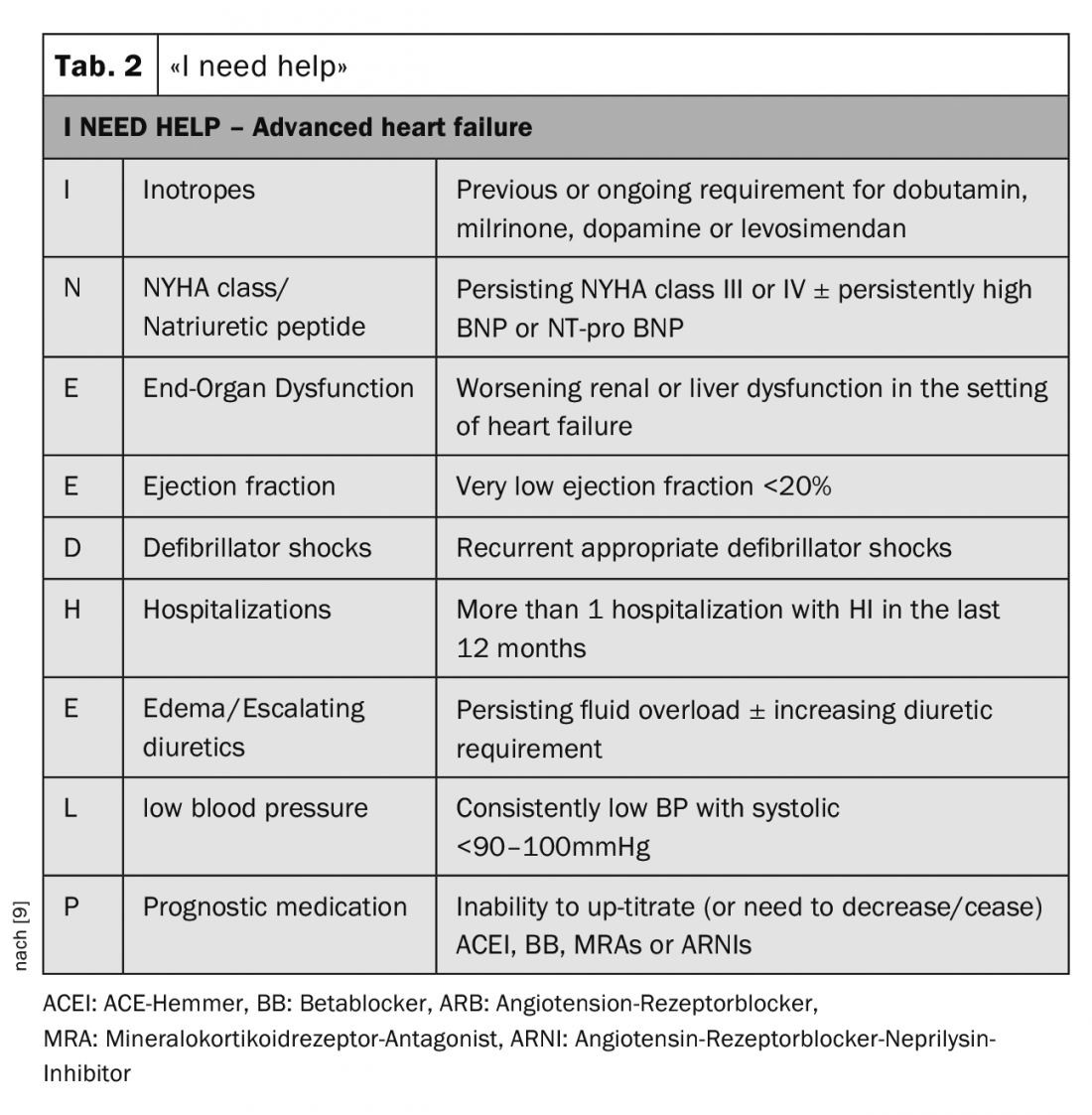

For identifying patients who need further evaluation at a center, the mnemonic “I need help” is very helpful (Tab. 2). In particular, patients with recurrent cardiac decompensation or those in whom it is impossible to increase heart failure medications or who even need to reduce them should be referred to a specialist for evaluation.

The final decision for or against an LVAD has to be made together with the patient, his family and the caregivers (e.g. general practitioner, cardiologist, Spitex), taking into account the patient’s wishes and lifestyle and including his social network (friends, relatives) (Fig. 1).

Take-Home Messages

- For patients with heart failure, we now have an increasing number of drug (sacubitril-valsartan), interventional (CRT, Mitralclip® for mitral regurgitation, ablation for atrial fibrillation) and technical (LVAD) therapies available. In order to give patients, relatives as well as the treating physicians the opportunity to discuss all available therapy options in peace and to find the optimal treatment for each individual patient, it is important to present them at a heart failure center as early as possible.

- For guidance on the latest time patients should be sent to an HI specialist, use the mnemonic “I need help.”

- In recent years, better patient management as well as technological advances have led to a reduction in serious complications (e.g., pump thrombosis, stroke) for patients with LVAD. Due to the simultaneously increasing shortage of donor organs, LVAD implantation is therefore a good alternative for more and more patients with severe heart failure.

- Patients with INTERMACS profile 5-7 and preserved quality of life should wait with LVAD implantation. Close monitoring is essential to avoid overlooking the first signs of often rapid deterioration and thus prevent risky high-risk interventions.

- Patients with INTERMACS profile 5-7 with impaired quality of life must weigh whether they are willing to accept an increased rate of complications for the chance to improve quality of life.

Literature:

- Yancy CW et al: 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of heart failure: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. (Adapted from Stevenson et al. INTERMACS profiles of advanced heart failure: the current picture. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2009;28:535-4). Circulation 2013;128(16):e240-327.

- Kirklin JK, et al: J Heart Lung Transplant 2018; 37(6): 685-691.

- Starling RC, et al: Risk Assessment and Comparative Effectiveness of Left Ventricular Assist Device and Medical Management in Ambulatory Heart Failure Patients: The ROADMAP Study 2-Year Results. JACC Heart Fail 2017; 5(7): 518-527.

- McMurray JJ, et al: Angiotensin-neprilysin inhibition versus enalapril in heart failure. N Engl J Med 2014; 371(11): 993-1004.

- Marrouche NF, et al: Catheter Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation with Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(5): 417-427.

- Stone GW, et al: Transcatheter mitral-valve repair in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med 2018; 379(24): 2307-2318.

- Milano CA, et al: HVAD: The ENDURANCE Supplemental Trial. JACC Heart Fail 2018; 6(9): 792-802.

- Mehra MR, et al: Two-Year Outcomes with a Magnetically Levitated Cardiac Pump in Heart Failure. N Engl J Med 2018; 378(15): 1386-1395.

- Baumwol J: “I Need Help”-A mnemonic to aid timely referral in advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant 2017; 36(5): 593-594.

CARDIOVASC 2019; 18(1): 16-19